Over Christmas, I deflowered a middle-aged friend of his Nutcracker innocence. A typical European, he’d seen Pina Bausch but no Petipa. Though I suspect he found the whole thing childish, he responded gamely (this was to ABT’s new Ratmansky version) except to the pas de deux. These moments of slippery idealized romance made him itch. In fact, he decided BAM was infested with bed bugs.

That’s not far from my reaction to reviews that separate the dancer from the dance–gushing about a dancer, say, with only passing reference to the ballet that defines her and that she embodies for the night.

The method smacks of nineteenth century balletomania, in which fans treated the choreography as the ballerina’s vehicle, not her legs. In reaction, Balanchine insisted that in his company the choreography would be star. He knew that if the ballets were any good, the dancers would be in no danger of being taken for granted. In fact, they would be recognized for their talents as dancers and dancer-actors, not for qualities somewhat at odds with dance, such as “personality.”

I got to thinking about all this during New York City Ballet’s winter season (yeah, I’m a month late in posting here), because to my joy the Financial Times asked me to review a fair number of repertory pieces. I wrote on Symphony in Three Movements, seven Balanchine works for the choreographer’s birthday party, Christopher Wheeldon’s Polyphonia, and Peter Martins’ full-length Swan Lake, which I had reviewed for FT as recently as last year.

I had the luxury of spending some of my 400 words on the dancers: a thrill, as I love NYCB dancers. But I wanted to talk about them in a way that gave both them and the dance their due. My rule for myself was, Write about the dancers in so far as you can say how they are shaping the dance.

Whether or not I did a good job, I wish more critics would follow this rule. It would eliminate the semi-pornographic, wholly dispiriting tone of connoisseurship–ah what a nice wine, a nice pointed foot, a slim ankle–that occasionally still creeps in to “fine arts” reviews. (Reviewers of the popular arts–pop music, movies, theater, etc.–may at times be frivolous, but they would be run out of town if they adopted such a sniffy tone.)

Here is the start of my review of Balanchine’s Symphony in Three Movements, with Janie Taylor shaping her role in such a way that made the whole ballet take on new aspects–or at least made me aware of them. (For the whole review, click here).

Balanchine ballets may be timeless but they are also deliciously of their moment, especially the experimental works – where you least expect it. Created for New York City Ballet’s 1972 Stravinsky Festival, Symphony in Three Movements (which repeats in the spring) comes late to the modernist party. Balanchine celebrates this with a pop-Modernism, decked out in bubblegum-pink as well as the usual black and white.

Stravinsky includes in his symphony odds and ends accumulated during the war years: a soundtrack for a US newsreel of Hitler’s advancing army, a rejected score for the 1943 Hollywood movie The Song of Bernadette. Balanchine responds with his own mainstream mash-up, but circa the late 1950s and beyond, when the automobile and automation were encouraging whole new species of frivolous motion.

A boy and girl (on Saturday Anthony Huxley and Erica Pereira in debuts) compete at jumping high, knees to their chests. The large ponytailed corps lap the stage in concentric circles, crouch prettily as if about to burst into a Broadway number, and form a chorus line to semaphore mysteriously. The three male leads catapult their partners into the air in a balletified form of swing dancing – with Megan LeCrone, pressing against thin air, especially riveting.

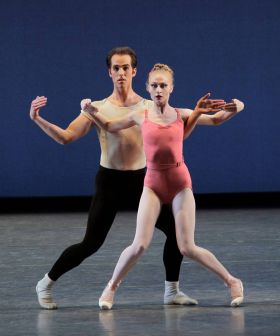

For the central pas de deux to Stravinsky’s plucky adagio, Balanchine concocts an Orientalist analogue to this sporty excess. A couple engages in ritual intimacy with crooked limbs and hinging wrists.

Janie Taylor, opposite Jared Angle (above; photo by Paul Kolnik), made an intriguing combination of impetuosity and doll-like dumbness, as if she were doing whatever popped into her head– except the pops came so slowly we could glimpse the void that preceded them.

The whole ballet works by that principle – or would have if Saturday’s corps had enjoyed enough rehearsals to risk split-second timing and more recklessness.

Click here for more on Balanchine’s ephemeral architecture in Symphony in Three Movements.

For Polyphonia (click for the whole review) I don’t spend much time on the dancers. I mention the ballet’s anchoring couple, Wendy Whelan and Tyler Angle, for bringing to bear on their performance a better sense of the ballet as a whole than their otherwise lovely and compelling colleagues.

Before Polyphonia, which turns 10 this month, Christopher Wheeldon’s pieces for the Royal Ballet, whose school he attended, and the New York City Ballet, where he danced, marked him as a major talent. After this modernist leotard ballet, created on eight dancers from NYCB, the young Brit was a sensation.

Polyphonia – which repeats in the spring – descends from the daring, flex-footed, angular Balanchine ballets that in 2001 were looking dangerously faint. Like Agon, The Four Temperaments and Symphony in Three Movements (gloriously paired with the Wheeldon on Wednesday), Polyphonia transplants us to a “forest of symbols that watch a person with their familiar gaze”, as Baudelaire, the quintessential modernist, put it. The symbols – in dance, steps – reorganise experience as a dream does.

Tyler Angle about to cantilever Wendy Whelan forward. Photo by Paul Kolnik for NYCB

Polyphonia‘s steps emphasise the grave balance between people. Tyler Angle carries Wendy Whelan on his back like Aeneas did his ailing father from burning Troy – except her legs are bent sharply over his shoulder like scythes. She straddles his hips like a plough and rotates her body full circle, like the shadow on a sundial. The images are ancient and mythical, rooted in heaven and earth.

Wheeldon uses the floor like the contemporary choreographer he is – the dancers lying and crouching there, and bending over straightened legs like storks. He honours Balanchine without repeating him.

Balanchine could alert you to the beauty and rhythmic juice of music you hadn’t paid much attention to. Likewise, Wheeldon organises the anarchic sound of Ligeti into beats and fashions a single organism from the 10 short numbers. At least that is how it is supposed to work. On Wednesday, with several dancers debuting in their roles, the ballet didn’t entirely cohere.

Or maybe it simply cohered differently. My memories of the premiere, in 2001, have strongly influenced my take on the current rendition of Polyphonia. Ah, the pull of that first time!

It is tempting to say that Sara Mearns is better than the Odette and Odile that the Peter Martins choreography hands her, but is that ever really the case? As long as a dancer is not inventing her own steps, can she ever be other than choreography embodied and inspirited? These are not rhetorical questions. I’m really asking.

In any case, Mearns was fantastic–made the ballet worth watching:

The hit ballet horror movie Black Swan may have galvanised the hordes at Swan Lake

(the nearly sold-out run continues until February 26), but telegenic

lesbian sex has nothing on ballerina Sara Mearns’ two swans, black and

white.Peter Martins’ uneven 1996 version of the iconic work

does little to set the stage for this momentous turn. The New York City

Ballet chief evinces the same impatience with plot as Balanchine, who

claimed that Swan Lake‘s story amounted to “a prince coming out

with a feather in his hat”. But in supplanting plot with poetry,

Balanchine’s two-act distillation clarifies and deepens the drama. In

contrast, the reams of steps in Martins’ four-acter are neither

adequate as metaphor nor fulfil the storytelling imperatives of

scene-setting and character development – except, thankfully, in the

crucial case of Odette the swan queen and her cosmopolitan nemesis

double, Odile.The prince, for example, arrives at his pivotal

21st birthday party with so little fanfare – despite Tchaikovsky’s

broad hints – that I mistook the jester for the guest of honour. For

the ballroom scene, the choreographer has sexed up the national dances

to prepare us for Odile’s seduction of the prince, but then adds perky

innocent numbers that throw us off the scent.

The end-stopped lines of Sara Mearns’ Odile; like a strong rhyme, they popped. Photograph by Paul Kolnik for NYCB.

Only

in the scenes with Odette and Odile does the ballet gain a reason for

being – one consonant with the Balanchinean values of speed, daring,

leggy breadth, and trust in the steps to tell the story.Mearns,

25, came to the public’s attention five years ago in this double role.

She was still in the corps and had yet to be singled out for anything.

The bone-thin principal dancer’s wide frame accentuates the

capaciousness of her movement: her valiant cavalier, Jared Angle, had

to run to support her in leaps around the stage.When the

huntsman-prince first stumbles into the woods, Mearns is a whirring

tumult, eventually quieting to a stateliness that intimates creaturely

strength – her leg crooked around the prince to anchor her as she

plunges to the floor. As the calculating Odile, she trades vastness for

blunt power, kicking her leg overhead as if punting a ball over a

goalie. Always she slips in and out of poetry, sometimes dancing as the

character and sometimes as the emotional air the character breathes.

At the wittily titled Balanchine birthday celebration “Saturday at the Ballet with George” (click for whole review) I was struck by how indelibly Suzanne Farrell has marked both Walpurgisnacht Ballet and Mozartiana. (I don’t mention it in the review, however.) You feel her in the high-stepping dressage and the way the turning and piqueing steps slide past each other, the dancer skipping a stop to continue spinning around herself. An exhilarating and dizzying effect in both ballets, it means something different in each.

This year, Balanchine’s birthday fell on a Saturday – an excellent day for a party, as any child knows – and New York City Ballet celebrated its co-founder from morning to night. Artistic director Peter Martins led a demonstration class for advanced students from the feeder school, current company members discussed what Balanchine meant to them, and of course there were the ballets – from The Prodigal Son, which Balanchine created for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1929, to Mozartiana, made two years before the choreographer died, in 1983 at the age of 79.

In a single day we hopped from pop Americana (Stars and Stripes) to constructivist fable (The Prodigal Son) to slippery elegy (Mozartiana) and reverie (Walpurgisnacht Ballet) – each ballet a master of its kind but none reducible to genre, and all immediately identifiable as Balanchine.

After seven works in a single day, you start making new connections: for example, between the angularities in The Prodigal Son that spell moral deformation and those in The Four Temperaments, two decades later, that suggest astringent clarity. Or between the ballerinas in the late works Mozartiana and Walpurgisnacht (respectively, supple and inward-leading Wendy Whelan and silky Maria Kowroski), who glide backwards while facing forwards as if slipping inexorably into the past.

A mechanical and seductive Kowroski reigning over her goons and the prone Prodigal (Joaquin De Luz). Photo by Paul Kolnik for NYCB.

More epiphanies from a bounty of Balanchine.

Leave a Reply