With dances that use an academic or codified language, the route to the matter at hand is relatively direct. Not so when not steps, not structure, but method–more intangible, less empirically provable–is the reigning force. In that case, it doesn’t do for the critic to isolate effects; they are mere flotsam–analogues. Of course, writers do isolate all the time, with the result that the dance sounds inane (which sometimes it is). The alternative, though, is to make the dance sound DOA–immaterial, purely ideational (which often it also is). Argh!

These two lousy and endemic approaches–along with the small audiences–probably make daily newspapers chary of covering experimental work. I love the challenge–but I also sympathize with my editors (and imagine their eyebrows raised).

Here’s a chunk of my Financial Times review of Ralph Lemon’s video talk slash dance at BAM, How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere? in which he cannot imagine dance as a vehicle for loss (though talking and video are okay):

More than most dances and multimedia works, Ralph Lemon’s How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere? has a message: art will always translate life inadequately. Because it attempts this impossible translation, How Can You (in the midst of a US tour) proves a paradox – fruitful at first, then exhausted by zealous doubt.

Since we last encountered the 58-year-old choreographer, visual artist and writer – for the third and final part of his Geography epic, in 2004 – Lemon has lost his partner to cancer. He recounts this awful fact seated in a white plastic patio chair near the front of the stage; beside him is a large video screen that will supplement his eloquent ruminations on the tenuous connection between life and art with scenes from both.

To ennoble his loss, he explains, he asked his small-town Mississippi muse – a man named Walter, aged 102 – to re-enact scenes from Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 Solaris, the most metaphysical of science-fiction films, in which a man in outer space hallucinates his dead wife. Walter, decked out in a homemade spacesuit, plays the husband and his 82-year-old wife, Edna, sits in for the resurrected wife.

The faux-wood walls and plethora of plastic furniture covers in the old couple’s home translate 1970s sci-fi tackiness with delightfully uncanny accuracy but their love has lasted too long to approach tragic hauntedness. This disjuncture turns out to be the point. All the mediations involved in an ageing one-time sharecropper rehearsing cinematic Soviet love scenes that stand in for the choreographer’s own recent loss cause us to become unmoored, like the grief-stricken.

How Can You relinquishes this layered depth, however, when…

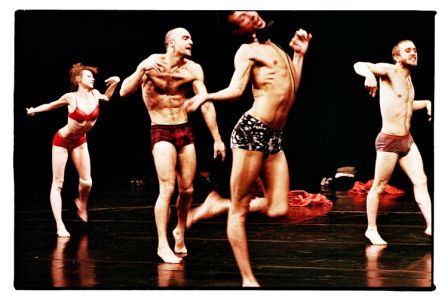

Second-act dancing. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

For the whole Lemon review, click here.

And here is the start of my review this week of Alain Platel’s Out of Context–for Pina, for the Flanders Ballets C de la B, which the choreographer founded in 1984. At the Joyce through this Sunday. The Platel is ultimately more engrossing than the Lemon; it may not not be so rigorous or smart, but it is also not so tunnel-visioned. It doesn’t succumb to reductio ad absurdam thinking. The dancers are allowed to matter:

If Brueghel and Bosch had met, they might have come up with Alain Platel’s Out of Context – for Pina, a panorama of movement ranging from the mechanistic to the deranged.

The stage is a hive of divergent activity. At any given moment – or the best moments, anyway – in this desultory two-hour show, one cluster of dancers may be progressing methodically from bone to bone and joint to joint in a cubism of motion; another group stand far upstage with their backs to us like stone goddesses, chests bare and orange blankets tied around their waists; and a man and woman play prehensile footsie. The intrigue in these semi-private dramas is the body’s imminent unravelling.

In the first New York appearance of Les Ballets C de la B since 1996, the nine highly individual dancers protrude their butts, hang their heads, loll their tongues, and let their ribcages slip and slop, their eyes grow askew, their feet smack the floor. They do this in unison – that paragon of order. The border between “movement disorder” and “dance” begins to warp.

Disordered. Photo by Chris Van der Burght

Inspired by the motor disease chorea, Platel – a movement therapist before he was a choreographer – wants to discover the common ground between these extremes, dancing and disorder. From the evidence, I’d venture that it is extravagance. The difference is that virtuosic dancing pays for its excess with the body’s skilled economy. Disordered movement, on the other hand, is excessive through and through; it blurs periphery and core, the essential and the extraneous. A dance with a messy structure can give pleasure, as Platel’s does, but a body in disarray turns out to be agonising to behold, out of context or not.

So Out of Context – for Pina mixes intermittent agony with the pleasure….

For the whole C de la B review, click here.

The most interesting part of your review of Lemon’s “How Can You” is the last two paragraphs:

“[The dancers] look discombobulated and harassed by effort. Like most things in life and unlike art in all its subterfuge, their bumping and falling stands only for itself.” Here you seem to say (for good reason in my view) that the work is not dance, not art. (I wonder what Arlene Croce would have thought.)

Then this: “I think: ‘It must be more engrossing to do than to watch.’ And then I think of other things.” What things?

Louis Torres, Co-Editor, Aristos (An Online Review of the arts) – http://www.aristos.org

[Apollinaire responds}

Dear Mr. Torres,

Thank you so much for your thoughtful and interested response. Yes, I guess I would say that in the second act, Lemon succumbed to such radical doubt, he took all his tools away from himself and ended up with a bit of life, without the heightened affect of art.

As for what I was thinking–I can’t remember, as the thoughts were on the periphery of my watching: scattered.