But first: to all of you who came out on a blearily hot summer morning for my talk for the Dance Critics Association conference (see previous post ): thank you. It was lovely to meet those of you I’ve only corresponded with or haven’t even done that, to see those of you I know, and to receive such a warm and interested response.

Some of you who couldn’t make it have wanted to know how you can hear the talk. I think there will be a video–though probably not for some weeks. If and when there is, I will post it here. If there isn’t, I’ll see about an mp3.

In the meantime, here are chunks of four reviews from the last two weeks, finally updated with photos and some commentary.

My essay/summary of the four farewells at New York City Ballet–of Darci Kistler, Albert Evans, Philip Neal, and Yvonne Borree. Special prize to anyone who correctly identifies the “fellow believer” mentioned in my lede. One of the pleasures of June was getting to check in regularly with ballet friends.

“It’s like church,” a fellow believer observed of the Sundays in June we were spending bidding farewell to principal dancers at New York City Ballet – one per week. And, indeed, there is a reassuring ritual sameness to these leave-takings. (Not so during Balanchine’s lifetime, when your fate fell to one extreme or another: either to fade away or to be sent off in royal fashion, with a new ballet as your goodbye present.)The programme begins like any other, except that the guest of honour has chosen the ballets. But after the final curtain calls, the dancer ends up alone on the vast stage. Soon, past and present partners file in to fill her arms with flowers and her lips with kisses, and to cry. Next, the younger generation shows up, smiling sheepishly as they each offer a single rose. Finally, ballet master-in-chief Peter Martins arrives to bless the dancer’s afterlife.

When the curtain descends and rises once more, the dancer is alone with us again. It is almost impossible not to ache. Besides the intimations of mortality, everything about how this person leaves reminds you of how he or she has danced.

Yvonne Borree – age 40, with the company for 22 years – was one of those principals who preferred to share the spotlight. She regularly elicited the most ardent attention from her partners – and did so again on June 6. During the ovations, the recently retired Damian Woetzel handed her his heart, or at least the Steadfast Tin Soldier’s paper cut-out. The ballets were romantic, too. For Balanchine’s Duo Concertant, Borree and the gallant Jared Angle were perfectly attuned to each other, whether alternating solos or standing side by side and hand in hand listening to the violinist and pianist. At the ballet’s end, a spotlight homed in on Borree’s hand. Angle clasped it in both his own. When he released it, it fluttered up like a dove in the dark.

Jared Angle giving Yvonne Borree his all for her final Duo Concertant. Photo by Paul Kolnik for the NYCB.

Philip Neal, 42, who has danced with the company since 1987, is a soft, bright Apollo – still. Of the four, he departs with his technique most intact. On June 13, he went out with Balanchine’s Chaconne, one of the most devilish roles in the repertory, delivering the wide, sharp steps cleanly and at top speed. But he doesn’t call attention to himself; a classicist, he effaces himself for the dance’s sake. As his ballerina, regular partner Wendy Whelan danced entirely for him. In a jiggy solo, she caught his eye at every phrase’s end. He smiled a little; if he had smiled more, I think he might have burst into tears.

A final reverence to the genius on the wing from these longtime partners. Photo by Paul Kolnik for NYCB.

After the bouquets and the parade of ballerinas and his life partner kneeling at his feet, Neal spread his arms and bowed his head in gratitude.

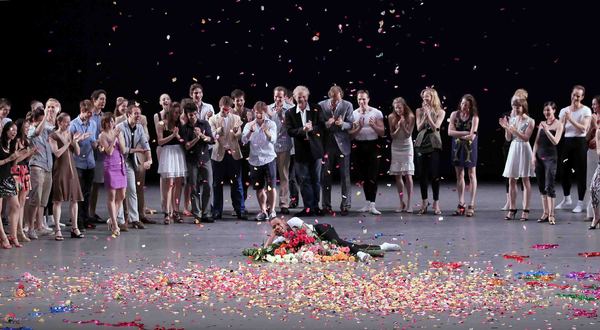

Albert Evans among the flowers. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

For the whole piece, click here. Because I am late in posting this, you will have to register to read, but registration is free and you only have to do it once.

Review of three newish casts in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet at American Ballet Theatre–David Hallberg and Gillian Murphy; Herman Cornejo and Xiomara Reyes; and Cory Stearns and Hee Seo:

In the past half century, it has become a rite of passage for a choreographer to mount his own Romeo and Juliet. There are now many. But none can claim the popularity of Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s 1965 creation for the Royal Ballet, immortalised on film by Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev. The Royal Ballet has performed it some 400 times; meanwhile at American Ballet Theatre, Romeos and Juliets have loved and died nearly every year since MacMillan set the ballet on the company in 1985. After watching three ABT performances over two days, I can vouchsafe that while your heart may break, the ballet only grows stronger with multiple viewings.

Driven by Prokofiev’s emotionally dense and variable score, the action shifts seamlessly from the bustle of a Renaissance town square to the chilly ranks of guests at the Capulet ball to the warm cocoon of Juliet’s bedroom. The steps delineate complex emotions, even for the chorus – Juliet’s band of blushing girlfriends, for example, or the flea-ridden whores. And for the illustrious lovers, the choreography is elastic enough to sustain multiple interpretations without loss of poetry. Plus, the ballet is sexy. The balcony scene – a sustained pas de deux of coital lifts and plunges to Prokofiev’s overlapping crescendos – is the gold standard for contemporary ballet romance.

On Tuesday night, lean, brooding David Hallberg and his forthright lady, Gillian Murphy, caught the music’s wave and rode it in. But the way the two looked at each other mattered more….

Oh, the incline of those necks! Photo by Rosalie O’Connor for ABT.

For the whole review, click here.

Review of Johannes Wieland’s very intriguing and promising roadkill at Dance Theater Workshop a couple of weeks ago:

Johannes Wieland’s ingenious roadkill transpires on stage, on screen and, most suggestively, in between. The dance-cum-video by the Kassel State Theater’s recently appointed resident choreographer consists of a double duet. Harassing the live dancers Eva Mohn and Ryan Mason are their hip screen doubles high on the theatre’s back wall. “Eva, relax,” orders her outsized celluloid self via English subtitles. In knee-high boots and lilac miniskirt, this casual screen goddess belongs in some European art film from the 1970s – Wim Wenders’ The American Friend, say. An identically dressed Mohn , squatting on the floor, stuffs her head into her leather satchel. “Hey, Eva,” her double continues, “have some fun.” The dancer hurries across a tiny patch of ground with steps so small they would do a centipede proud.

Mohn and Mason squared. Photo by Nils Klinger.

Meshing video, dance, avant-rock composer Ben Frost’s chameleonic score and a set that conjures an abandoned aircraft runway, with its borders of trash and rotting leaves, roadkill depicts a state of self-alienation that tips easily into numb ennui or useless frenzy. It captures this limbo with admirable economy, but then founders. Halfway into the hour-long work, I am tired of these people, with their fake dilemmas – their “Should we have fun or make a plan?”

Wieland might have taken a lesson from those wanderlust films he invokes….

I especially admired Wieland’s smart use of video: not the usual temporal geography whereby the screen signifies what has already happened and the live dancers what is happening. These screen figures already know what is going to happen to their puny, anxious live versions. They are ahead of them, like celluloid greek gods: untouchable, bemused, long past ready for their closeups.

For the whole review, click here.

Finally, last week, glorious weirdo Saburo Teshigawara, installation artist cum choreographer and dancer:

I defy anyone to describe Saburo Teshigawara’s Miroku without sounding like an exhumed hippie. The 56-year-old cultishly adored Japanese choreographer’s dance plus light installation is an oxymoron: a performance of living. The title refers to a prediction of the Buddha before entering nirvana, about the perfection of an earthbound life, but it will also resonate with contemporary fans of anime and manga, where a Buddhist priest action hero goes by the name. If the loud, shape-shifting solo works for you – and it did for me, though it took some initial adjusting – you leave the theatre feeling as if you have just emerged from a bout with the elements.

For an hour within three colour-shifting walls, Teshigawara’s dancing slips from the palsied to the buttery, with patches of alert stillness, in which he assumes a sculptural pose. With his big, knobbly, bald head, thin neck and beautiful, concentrated face, this handsome ET moves his arms as bonelessly as tendrils, or as sharply as flames of glass. His rubbery legs can seem to be….

This photo, by Stephanie Berger for the Lincoln Center Festival, conveys better than I did the Rothkoesque quality of the walls’ moving painting. It had that spiritual, fuzzy-edged glow.

For the whole shabang, click here.

Living in Seattle, I don’t see NYCB often enough to have big opinions about the quartet of retirees you describe here, but I thought it was interesting that Borree chose Duo Concertant as a final performance, since earlier this season I saw Gavin Larson of Oregon Ballet Theater in a farewell performance of the same ballet. I love the dance for all kinds of reasons, but this accidental pairing makes me think of it again, as a way to say goodbye.

[Apollinaire responds]: Hello, Sandi! I realize that I met you at the DCA without realizing it was you until afterwards. Well, belated hello! That’s interesting about “Duo Concertant” as farewell. It does feel that way: someone fading away piece by piece, becoming absorbed into the darkness.

Thank you for writing.