So, unlike Movin’ Out, which was almost unanimously hailed (though not by me) or the Dylan dancical, which nearly everyone despised (including me), Tharp’s third foray on Broadway in the last ten years, Come Fly Away–to a Sinatra medley, with the man singing, inimitably, from the grave and the orchestra live–has divided critics so drastically that the New York Times staged a contretemps between its theater critic Charles Isherwood (pro) and its chief dance critic, Alastair Macaulay (con).

Both critics were at their worst, with Isherwood equivocating before recognizing what he was up against and Macaulay resorting to the sort of surliness that sours debate. When Macaulay asserts, “The nightclub where people need to keep carrying on like the pathetically exhibitionistic creeps in ‘Come Fly Away’ is not a nightclub in which I want to stay; they’re bores,” what else is there for Isherwood to do but repeat his words? “‘Pathetically exhibitionistic creeps’ “? But also “‘bores’ “? Still, the nature of their divide has been pretty typical.

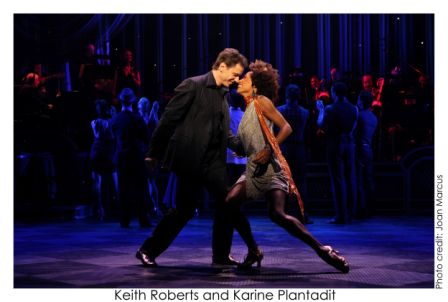

Complaints have centered around the weakness and flatness (and, less often, dislikability) of the characters, the choreography’s vulgarity and busy-ness, and the lack of story. Those who enjoyed the show–I’m one of them–agree it doesn’t have profound characters, but it does have profound dynamics between them. Example: when the more passive member (Keith Roberts) of a frisky, taunting couple suddenly turns the tables to push his partner around–and she (Karine Plantadit) thrills to it. I’ve known couples who were ugly like that, and Tharp is brave, novelistic, to show it.

People that liked Come Fly Away also didn’t mind that it didn’t have much of a story beyond the portrayal of these couples in love and war. The Dylan and Billy Joel dancicals did try to tell stories, and diminished the songs in the process (or Dylan’s songs; Joel’s came small). Come Fly Away doesn’t try to turn a song into a story, it turns a Broadway show into a song–or rather a ballet.

I confess, I thought the first act was too wham-bam. My muscles ached watching it and I wished all the dancers except former Cunningham dancer Holley Farmer, who maintains an insouciant ease, would honor Sinatra’s own example and cool it. (You can be tough–menacing even–while cool. In fact, if you’re going to be effectively threatening, you have to be cool. Get hot and bothered, and the game’s up.) When intermission hit I wondered where Tharp could possibly go from here: she seemed to have taken each couple’s dynamic as far as possible.

But in the exceptional second act, she shifts gears. It’s not the characters she takes farther, it’s the dance–and dance on Broadway. When she enters us into the late night dissolution populated by only the lonely, still out and nursing their wounds or drowning them in drink, it turns out to be a familiar place for concert-dance goers: a dream world, with a poetic logic that rides over and under the occasion and thickens it by contrast and complement.

At one point late along, the dancers clasp hands and do a little grapevine with their backs to us like you might find in a play inside a play of Shakespeare’s, put on by “mechanicals”. The folk dance gratifies a need for connection that all the coupling in the world–the world according to Tharp–cannot satisfy.

Here’s a piece of my Financial Times review, which came out about 10 days ago:

Twyla Tharp imagines romance as a war of wills. Frank Sinatra injects even the most googly-eyed song with a strain of menace, as if he had fallen in love despite himself. The two are a perfect match, and Broadway’s Come Fly Away proves it in startling fashion.

Tharp’s third jukebox dancical has as much working against it as the heavy-handed Movin’ Out, to Billy Joel tunes, and the Dylan flop that followed. The script amounts to a medley of songs, which Sinatra delivers on tape to the accompaniment of a live orchestra. The setting resembles a nightclub in an airport. The show doesn’t really feature characters – we would need a plot for that – so much as romantic propensities. One couple gravitates towards innocent clownishness; another maintains a cool insouciance; a third begins with grandstanding and friskiness, detours into spirited S&M, and finishes off with the aqueous lovemaking that emerges from sleep.

And yet Come Fly Away far surpasses Tharp’s other two Broadway shows because she has finally accepted what a song can do better than it does plot and character. In a seemingly casual arrangement of the most inventive dances she has created in years, the choreographer concentrates on metaphor, feeling and rhythm: poetry.

Perhaps to reassure the audience, the first act resorts to the usual Broadway tropes, but rendered with masterly precision. The eight leads don’t just strike a pose when they saunter one by one down a staircase, they freeze on the hippest beat of the hopping “Come Fly With Me” as if a flashbulb had gone off.

By the second act …..

For the whole review, click here.

Leave a Reply