A friend called Thursday night, and I was slow to pick up. When we finally caught each other, he quipped, “Yeah, I know, you’ve been busy mourning Michael Jackson.” But I’d been mourning him for years.

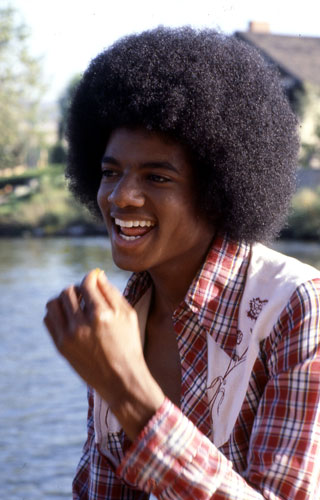

A young Michael Jackson (by Kate Simon, via the New Yorker)

Every time I saw a photo of Jackson more bleached, more narrow-nosed, more hidden behind glasses and scarves, than ever, I felt incredibly sad, and also implicated–part of a culture that devours its artist-celebrities whenever the glossy shell of celebrity they need for protection doesn’t suit them. Jackson didn’t want to be devoured, so he offered up a more and more dubious likeness of himself.

To New York Times editorial writer Verlyn Klinkenborg’s excellent point that Jackson’s “was a music we wanted to visualize, to see formalized and set loose in dance,” I want to add that the singer did some of the best visualizing himself. He changed the ground beneath him and the air around him when he danced. He could skate along the floor without hardly lifting his feet and, in the aptly named Moon Walk, he concentrated all of his virtuosity on getting his feet on the ground rather than off, like he really was on the moon. (And maybe he really was.)

In a thoughtful tribute to his dancing, Times critic Alastair Macaulay compares Jackson with a whole bunch of performers, but doesn’t mention the ones I’m most reminded of: Charlie Chaplin and the legendary tappers the Nicholas Brothers. Here’s Chaplin singing opera–sliding backward thickly like a matador and stepping jauntily like Jackson likes to do, too (the Chaplin clip has been hard to pick because it’s not a particular move but flickers of resemblance I’m struck by), and here are the tuxedoed Nicholas Brothers sliding and jumping over their own legs and changing direction on a dime in Down Argentine Way from the ’40s and then, 30 years later, doing the disco thing with none other than Michael and the Jackson Five, letting the pelvis carry the feet:

Though the tone is entirely different–Jackson isn’t a comic like Chaplin, and Motown and disco intervened between his kind of debonair and the Nicholas Brothers’–these lithe men also could travel while still standing on their feet, because they also were strong in the middle and light at the periphery. Jackson is their hyperbole.

His funky musicality helps with the magical exaggerations. He moves on the downbeat, which makes the transitional steps slide by as in a flipbook, where they fall between the sheets.

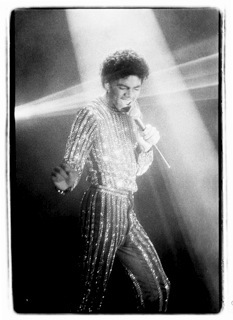

Here Jackson is in a 1983 Motown celebration and here he is doing the moonwalk, and here he is, in the trippy video for “Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough,” being his

charming young-man self (I love the leg waggles, the turned out feet, the laid

back torso, the easy, swinging pelvis–the whole loose gangly thing. And, yeah, I know, these aren’t the moves that revolutionized–made a feat out of–pop-star dancing, but he does do them like no one else: looser, easier, and more shy.)

For other possible influences, here is a fantastic Youtube montage

of everyone from Bill “Bo Jangles” Robinson to Eleanor Powell, Earl

“Snakehips” Tucker, Tip, Tap, and Toe, and a whole host of other 20th

century luminaries I should have heard of. (But not Jimmy Slyde–he

should be in here somewhere).

And for a 1984 parody of the MTV “Billy Jean” video, here’s Steve Martin.

My friend, Foot contributor Paul Parish, who, a couple of years ago when we were talking about who could be our ambassador, our Pavarotti, of dance, was quick to offer Michael Jackson, writes this morning (Monday) to say:

The thing is, Jackson’s dancing really translates into video — it’s pure terre-a-terre dancing, no loft to it at all, and the tiny changes he’ll make in his profile register with alarming clarity on the two-dimensional screen. I agree with Alastair, it’s so premeditated I kinda hate it; it’s so determinedly cool, everything that’s NOT cool has been edited out, and at some level I devoutly believe that’s what killed him. I thought he was going to die in his last show — it frightened me, he looked like he could not breathe. I was not surprised to hear that he’d died. The first thought that went through my head when I turned on the radio and heard it was, “Of course.”

My friend Brian Seibert, critic and tap historian, writes this afternoon (Monday):

Chaplin and The Nicholas Brothers as precursors for MJ? Certainly. Jackson was a sponge, a sampler, a great appropriator. And as your twin examples demonstrate, he had no prejudice about the sources he stole from. That’s obvious in his earliest recordings, the kid who can so amazingly mimic his elders, suggesting adult emotions through adult style. (Young Harold Nicholas was like that, too, channeling Cab Calloway instead of James Brown.) But Jackson was just as precocious in his physicality. Forget Man in the Mirror; the man was a mirror. And his precocity, his magpie mimicry, was daring. “The Origins of the Moonwalk,” the illuminating YouTube compilation you mention, leaves out his most immediate models: the Godfather of Soul and the lesser-known Jackie Wilson and all of the Motown groups Young Michael grew up among, all doing the steps of the tap-dancer-turned-choreographer Cholly Atkins. Yet the compilation suggests the deep tradition behind Jackson — the moonwalk was older even than that 1940s clip of Bill Bailey — and includes Sammy Davis, Jr., a precocious black hoofer who first made it big by doing impressions of white celebrities. The impressions were so dead-on that they were mocking, which frightened Sammy’s older stage partners, his father and his “uncle.” But Sammy wasn’t going to accept any artificial limit on his influences, his talent, or his audience. Jackson took it a few leaps further, and he paid a similar price: the usual pressures of child stardom and extreme celebrity, but also a chameleon’s uncertainty about who he really was. After Bad, the influences that resonated through Jackson’s dancing narrowed, or they became less about dancing and more about spectacle (for instance, the odd, fascist aesthetics of History). I suppose the protests-too-much crotch-grabbing was an attempt to stay current, but by that point, he was beyond imitating others. He could only imitate himself. And so as his appearance morphed horribly, his style stayed fixed; now he resembled his imitators, the way that Sammy Davis came to resemble Billy Crystal’s version.

This week’s New Yorker piece by Kelefa Sanneh about how much of “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin'” came from Manu Dibango raises questions about how much Jackson stole and how much he added, questions that are even more equivocal when it comes to dance and dance’s more fluid and weaker notions of copyright. What isn’t equivocal is how Jackson inspired a passion for dance in millions.

He was my entry. It was that famous “Billie Jean” performance at the Motown 25th. He moonwalked a white, middle-class nine-year-old in suburban LA into acquiring a miniature Beat It jacket, the spangled socks, the single, sequined glove. More important, he moved me to learn the choreography to all of his videos. I made my father film me re-creating them. As anyone who’s seen me dance at a wedding can confirm, I still remember those moves, and everyone in my generation recognizes them immediately. It was decades after I learned them that I learned to recognize where they came from. That took some research. But Michael was the introduction, as he was for so much of the world.

That clip of Jackson with The Nicholas Brothers, by the way, doesn’t show any of them to advantage. As moving as it is for the Jacksons to invite the brothers onto their variety show–an outlet that the Nicholases never had, and Sammy had only briefly–that routine finds the entertainers meeting in the shallowest part of showman’s versatility, the Vegas they shared. That they shared deeper things is abundantly clear in their better, more sui generis performances, also wonderfully available on our new library of dance, Youtube. Who’s being inspired, online, right now? — Brian

I respond:

Brian, Thank you. I wish I could get my hands on that video of you doing your Michael impersonations.

I agree, the Nicholas Brothers’ meet-up with the Jackson Five doesn’t show them to advantage–readers, click on this link to Down Argentine Way for that–but I didn’t even know Michael could tap; I liked watching him do it.

Being older than you–how much? a decade?–I don’t associate Jackson with being cool, but with getting to be a young child for a bit longer: how great that even when you were in third grade and reading chapter books, you could still sing about the ABCs and 1-2-3s! (I was six when the ABC album was released, but don’t remember hearing the song for another couple of years.) Yeah, I associate Michael Jackson with childhood, and I think he did, too, growing up in reverse, to catastrophic effect. (Maybe those recent movies about men starting at age 70 and working backwards–Youth against Youth and Benjamin Button–were inspired by him.) By junior high, I’d “graduated” from the Jackson Five to Earth, Wind, and Fire, the Commodores, and Tower of Power, and by college everyone was doing the Robot and the Moonwalk, and I didn’t know where those moves had come from, they were that viral, but guessed it had something to do with the boys spinning on cardboard on their heads on the street. Wrong again. My chronology was–as it is–full of holes of inattention.

I too hope someone’s being inspired now.

A beautiful Jackson at 20, in 1978, smiling, not dancing.

Leave a Reply