When my niece, Hannele, was an infant, she would light up

whenever you turned on the light, staring at this facsimile of the sun with curiosity

and awe. For her little brother, Pascal, music had the mind-altering effect. Light

took my niece out of herself; music pulled my nephew into itself. He’d close

his eyes and let his head fall back in a swoon.

Dance often moves in fruitful counterpoint to music, with the

one illuminating not so much the other as a third thing–the piece. But sometimes

a choreographer fuses the two and you fall into a trance. You know the dance is

working, but you are too far in to know how.

I didn’t like Christopher Wheeldon’s “Fools’ Paradise” at

its New York City Center premiere last year, when his pick-up company, Morphoses,

debuted. The ensemble work to Joby Talbot’s eerie neo-Romantic foreboding of violins

came at the end of an evening with so much Wheeldon, you got tired of him and

began confusing means with ends–wishing the choreography weren’t so sculptural

and static, hoping for an occasional rush of movement where everyone stood on

their own two feet.

This year, Wheeldon curated Morphoses’ pair of programs more

carefully. Duets no longer dominated and the Frederick Ashton trio “Monotones II”

seemed like a perfect companion to Wheeldon in its sweetness and the equanimity

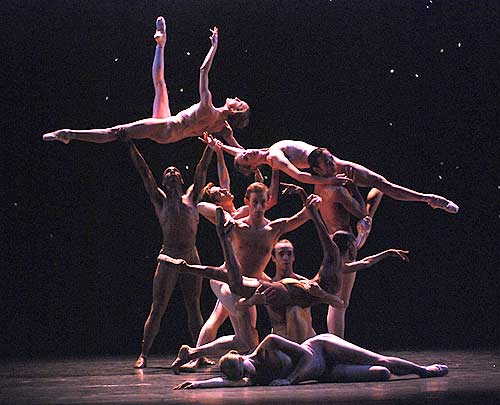

between dancers. “Fools’ Paradise” now suited its name. It was the paradise of those who inject the dread of the inevitable

fall into the idyll before, so the bad part doesn’t seem so bad. It was a dance for those who have counted melancholy a joy. With the dancers in fleshtones and

bathed in a waning glow under a light rain of glitter, “Fools’ Paradise” perfectly complemented the Indian summer outside–with its steady warmth shadowed by the presentiment of winter chill.

“Fool’s Paradise.” Last year, static; this year as warm and ephemeral as an Indian summer

Normally I’d offer you an emblematic moment to illustrate the delicious and fragile atmosphere the dance enveloped us in, but I’d left

my reviewer’s mind behind, because after last year’s experience I wasn’t expecting

much. I’d settled for the default setting when nothing much is being asked of me

and I’m just happy to sit in the dark and take in a show. My attention became recessive

and my gaze panoramic. I was more wordless (unlike many–better–writers, I don’t

feel in words, I only think in them) and receptive.

The result was a keen sense of the ballet but few details to

hang it on–and a hunch that my accidental approach was just right for Wheeldon.

After testing this hypothesis on a second viewing of his “Commedia” (for Morphoses) and

the New York premiere of “Within the Golden Hour” for the San Francisco

Ballet’s 75th anniversary celebration at City Center, I was convinced.

Trained on Balanchine, most New York ballet critics absorb meaning

and sense syntactically, because with Balanchine it’s the action between the notes–the syncopated rhythms–that shape the steps and their portent. With Wheeldon, the

ballet’s color and emotion may be rooted in the score, but the organizing

principle is visual. In his “Commedia,” for example, he transfers

the sharp angles of the jester’s iconic shrug to legs, hips, and the surface

insouciance of secretly tender pas de deux. But if you scrutinize any one of these

gestures, it’s like standing with your nose pressed against an Impressionist

painting. The dots will make you dizzy–and you’ll lose the picture. Better to back up and let the motifs gradually seep in like a rising tide seeps in to sand.

In his six years as New York City Ballet’s resident

choreographer, Wheeldon set himself all sorts of genre challenges. He tried his

hand at the family-friendly ballet (“Carnival of the Animals”); the movie-musical

ballet ( “An American in Paris”); the tutu ballet (“Evenfall”); the modernist

ballet (“Polyphonia” and “Morphoses”). But whatever the genre, he eventually

gravitated to the same rich emotional terrain: the sadness of being too happy

in one’s happiness, where even requited feelings are in excess of their object.

The emotions Wheeldon favors aren’t operatic but subtly ambivalent, which is part of why he feels contemporary and people have faith that he can

carry ballet into the future.

Still, melancholy saturated in contentment is not an easy

mood to sustain–for us, anyway. While it was always a thrill to see Wheeldon beside

Balanchine and Robbins on a City Ballet program, presented in close succession on

a single night his ballets tend to cancel one another out.

skimming across the stage on point, the men manipulating their partner’s planklike

legs around a planklike torso, like a ballerina on a spit–the ballet you just

finished watching sticks to the moves and reduces them to gimmicks.

The problem

is not unique to Wheeldon–NYCB’s all-Robbins programs this spring suffered the

same fate–and he minimized it this time by using his own works as program bookends,

as far apart as possible. But the

promise of his company depends on him finding other exciting

choreographers with whom to share the stage. He had better luck last year, with Michael Clarke, Liv Lorent, and William Forsythe. This time, except for Ashton, he was the only one up to his level.

A bigger problem for Morphoses is the collapse of the economy.

Even in the best of times, a fledgling ballet troupe is an exorbitant and

risky venture: Balanchine emigrated to America on the expectation that he’d have

his own company soon; he waited 15 years. Of course, he did show up in the

depths of the Depression…. Hmmmmm…this is all beginning to sound very familiar.

There would be no shame in Wheeldon returning to the NYCB

fold until our economic troubles blew over (in–what?– 2018?). And perhaps now

that City Ballet has lost the Bolshoi director and choreographer Alexei

Ratmansky to ABT, who found no objection to the busy schedule that made City

Ballet balk, they will be extra generous with Wheeldon, letting him choreograph

whatever he wants, with first dibs on dancers, longer rehearsal periods, access

to the set and costume designers of his choice (his choices so far have been

wonderful), catered lunches!

New York City Ballet would be lucky to have him, and so

would we.

Next ballet stop: American

Ballet Theatre, at City Center for two weeks beginning this week. Their focus: Antony Tudor. Have you noticed how much more dance programming City Center has

offered this year? Besides the usual Fall for Dance, ABT, and Alvin Ailey,

there has been San Francisco Ballet and will be Lar Lubovitch next month. And

that’s just the Fall. Yay for City Center executive director (and former

Joffrey dancer) Arlene Shuler!

Leave a Reply