Jerome Robbins ballet is making me cringe, I think of Deborah Jowitt’s observation

in her wonderful Robbins bio that if the choreographer felt a conflict between

Broadway and ballet–the standard take on his career–it was only because of a more

fundamental opposition he set up for himself: between theatrical effect and

“the delicious ambiguity that dance permits,” she says.

The problem is,

it’s a false dichotomy. Theatrical effect and poetic ambiguity aren’t opposites, they’re on the same continuum. Ambiguity, metaphor, feeds off the concrete just as much as storytelling does. Robbins’ misunderstanding of what

people who are anxious about it tend to call “abstraction” caused him all sorts

of trouble–including “Watermill,” which reappeared last Friday at New York City

Ballet after a deserved rest of nearly two decades.

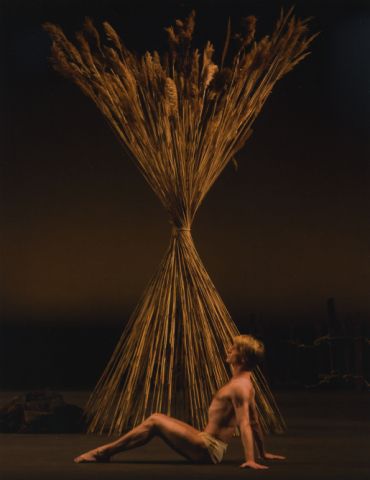

Nikolaj Hubbe in

“Watermill.” Photo, Paul Kolnik for New York City Ballet.

“Watermill” involves

a middle-aged man tripping on his life. (The captivating Edward Villella

originated the role in 1972; for this run, NYCB has recruited the recently

retired Nikolaj Hubbe, whose beautifully ravaged body is perfect for the part.)

Reclining among bundled stalks of marsh grass, the man hallucinates his frisky

youth, love affairs that went on without him, and a beautiful woman (Kaitlyn Gilliland) hypnotically brushing her hair. Teiji Ito’s flute and percussion score sets the meditative tone.

If a stranger said,

“I love a woman who brushes her hair,” he’d still be a stranger. You’d want to

know, Is it the untangling of her tresses, the sensuality of the strokes, the

ritual of hygiene, the way she inclines her head–what? Or, because you’d know too little to begin with, you wouldn’t

want to know anything. Even with its protagonist in his underpants, the most

naked thing about this ballet is Robbins’ earnest conviction that he’s saying something by leaving so much out.

Choreographers are still making this mistake–supposing that if they keep things open, they’re giving us more freedom to

imagine. Imagination doesn’t need

freedom, it needs something to dig its claws into. And Robbins proves again and

again with his unabashedly theatrical work (“Fancy Free” and “Afternoon of a

Faun,” for example) that he knows this. He knows that the situation and the steps–the denotation and the connotation–don’t run on

separate tracks. He knows that you don’t have more of one when you’re missing the

other.

But he forgets

nearly everything when he’s trying to be an Artist, rather than just make a

dance.

What, you still want to see it? As part of the Robbins celebration at New York City Ballet that lasts through June (33 Robbins ballets on 10 distinct programs), “Watermill”

plays once more, this Thursday, with the ebulliently goofy “Four

Seasons.” Cheap standby tickets for

students. Go to nycballet.com for details.

Apollinaire, you have this wonderful habit of putting into words thoughts that have circled in my head but never coalesced into neatly articulated sentences. Thank you!

I have never seen any of Robbins’ choreography outside of his film/Broadway work, and perhaps some other snippets show on TV, so I can’t really comment on your thoughts as they apply to his choreography…but I really think this statement of yours in particular, as it pertains to art in general (and especially downtown dance) should be front page news everywhere!:

“Choreographers are still making this mistake–supposing that if they keep things open, they’re giving us more freedom to imagine. Imagination doesn’t need freedom, it needs something to dig its claws into.”

Specificity brings art alive. And specificity does not eliminate ambiguity. Lack of sufficient detail leads to vagueness, which is not the same thing as ambiguity (and is usually much less interesting or desirable). Often, in fact, ambiguity is achieved by providing conflicting or surprising details. Shakespeare is full of detail and still inspires a rich multiplicity of interpretations. If only our dance were so rich!

Apollinaire responds: Well, thank you, Chris–I’m glad it made sense. I was a tad worried I was being unclear about vagueness (god forbid). I like the way you articulate the point, too. I think choreographers get in a bungle –and I’m going to add a short p.s. about this as soon as I have a chance–when they’re not resorting to narrative or other conventional means of drama. They’ve got stuck in their heads the equation of “poetic” and “vague.” Thanks for writing!