When in Tacoma, the last place on my list is the Museum of Glass. Its exhibits tend toward the didactic and its galleries have no natural light source, remarkable for a glass museum. With their low ceilings, they look like storage units.

Even so, I intended to see Preston Singletary: Echoes, Fire, and Shadows long before now. (It closes Sept. 19.) It’s hard to admit I was hesitant to see what MOG would do with this artist, but there it is. Fortunately, I was wrong. Not once inside this mid-career survey did I think about the limitations of the galleries. Credit goes to curator Melissa G. Post and the museum’s design crew. The show looks terrific.

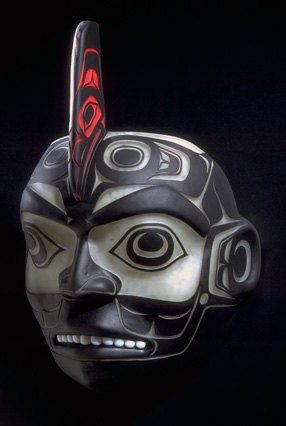

(All images reproduce sculpture by Singletary, taken from his website. Part of this post comes from a 2002 profile published in the PI. )

Singletary belongs to two tribes — the Tlingit nation into which he was born on his mother’s side, and glass, because glass at its core is tribal. In high school Singletary met lifelong friend Dante Marioni, whose father Paul took the boys to the counter-culture experiment in the woods that became Pilchuck Glass School. First generation artists in the studio glass movement were

Singletary belongs to two tribes — the Tlingit nation into which he was born on his mother’s side, and glass, because glass at its core is tribal. In high school Singletary met lifelong friend Dante Marioni, whose father Paul took the boys to the counter-culture experiment in the woods that became Pilchuck Glass School. First generation artists in the studio glass movement were

frequently at the house, and Singletary met them all.

After high school, glass offered an escape from college. Marioni managed to get his friend a job as night watchman at the Glass Eye. Thanks to his previous Pilchuck experience, he quickly moved onto the floor, blowing Christmas ornaments and other less seasonal decorations.

Glass was beginning to take off, and Singletary found himself along for

the ride.

What he liked best was the company. No other form of contemporary art is such a clan venture. With music

What he liked best was the company. No other form of contemporary art is such a clan venture. With music

blaring and heat pouring out of the furnaces, glass artists root for

each other, criticize, applaud and collaborate.

In 1984, after two years of glass factory work, Singletary became Ben Moore‘s gaffer. Moore’s studio offered not only a paycheck but the chance to blow with some of the best glass artists in

the world.

At Pilchuck, Singletary met Tony Jojola, who encouraged him to find a

At Pilchuck, Singletary met Tony Jojola, who encouraged him to find a

way to express his tribal heritage in the context of

contemporary glass.

In Alaska, he met David Svenson, a non-Native artist who opened up elements of Tlingit style Singletary hadn’t previously considered. Back in Seattle, Singletary thought the

hot glass bubble hanging precariously in front of him looked like a

Tlingit rain hat woven in cedar bark.

Eventually, he turned that shape upside down, transforming it into a

vase that all by itself would strike a familiar chord in Tlingit

circles.

Using a sandblasting and

Using a sandblasting and

stenciling technique he developed himself, he carved Tlingit designs on

the outer surface.

As Ramona Gault observed in a 1998 cover article in the magazine,

“Indian Artist,” the result is a “conical shape that opens upward like a

lily, its undersurface carved with an animal image that is split like a

Rorschach inkblot. When a light source is positioned above the vessel,

the carved image is cast in shadow on the surface where the vessel

sits.”

Beneath the stark, crisp clarity of his line, blunt old harmonies assert themselves. He

uses glass to express his Tlingit heritage, merging the ancient art of

glass blowing with even more ancient artistic practices of his people in

order to create a 21st-century version of tribal aesthetics.

He’s grateful for the Indian artists working in glass who came

He’s grateful for the Indian artists working in glass who came

before him, including Larry Ahvakana, Joe David, John Hagen, the late

Conrad House, Marvin Oliver and Susan A. Point, as well as his

contemporaries, such as Ed Archie Noisecat, who carved the masks

Singletary has used as molds.

Thirteen years before 1963, when Singletary was born, Robert Bruce Inverarity wrote that the art of the Northwest

Coast Native Americans was “flourishing when Captain Cook, on his last

voyage, reached the coast in 1778; it had passed its peak by 1910 and is

almost dead today.” Were he still alive, Inverarity would be happy to have been proved wrong. The glass end of the Northwest Coast tradition that began in Seattle has inspired Native artists around the world, and Singletary is among its leaders.

For those who need another reason to visit the Museum of Glass, Martin Blank‘s installation in the courtyard plays like frozen music.

Leave a Reply