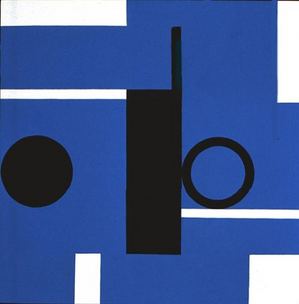

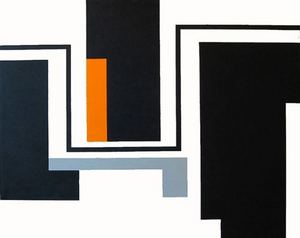

(Click images to enlarge. Portrait of Henry by former PI photographer Grant Haller. Paintings from Howard House.)

Art likes to contradict itself. Both voluptuary and ascetic, it revels in the sense world yet honors rigor, leads you astray and points to higher ground.

Its rules are made to be broken. Because those rules favor the young, unknown older artists who come on strong are particularly appreciated. Their example derails careerist thinking and restores a sense of possibility.

Few artists came on stronger in Seattle than Mary Henry, who died yesterday at age 96. An abstract painter who produced tough geometric forms filled with bright yet sour tonalities, she lived her last decades on Whidbey Island.

Few artists came on stronger in Seattle than Mary Henry, who died yesterday at age 96. An abstract painter who produced tough geometric forms filled with bright yet sour tonalities, she lived her last decades on Whidbey Island.

In summer her garden was a sight to see, and she tended it largely by herself until recently.

In a 2001 interview, she told me the place was all grass when she bought it.

I was only 60,

so I was able to do a lot of digging. I put everything in, from trees

and shrubs to flower beds. Someone helps me by mowing and trimming the

shrubs. I don’t do it all alone. I garden in the summer and paint in

the winter. The rest of the year, it’s a little of each.

She left golden grass growing in silky clumps in her meadow. Everything else, she put there: water lilies on her

pond; giant rhododendrons on gently rolling hills; beds of blue

bonnets, fragrant lavender and pink, papery poppies; wine grapes on

trellises; flowering plum and apple, and wild, yellow roses leaning out

into the light from tops of trees.

Born in Sonoma, California, Henry worked as a muralist on the Federal Art Project during the Depression and studied with the Hungarian designer-photographer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy at the Institute of Design in Chicago.

She married, had two children, stopped and started painting repeatedly, with little encouragement or notice.

It’s a fairly normal curve for women artists, especially women of her generation, circumscribed by paternalistic dismissal and then clobbered, like everyone else, by the catastrophes of aging. But instead of fading into her seniority, Henry surfaced in her mid-70s with triumphant, joyful work.

It grew directly from her experience at Chicago’s Institute, known as the New Bauhaus after the famous German institution that sought through abstraction to join the worlds of the spirit and the everyday.

Her work derives from…

the period when abstraction was a search for divine form, the universal underneath the particular.

The modernist imperative to “Make It New” accelerated the usual process

of change in art. Movements came and went with dizzying speed, yet

Henry remained focused on exploring her own rigorous interpretations of

early 20th-century abstraction.

She had the free-hand confidence of someone who turned visual tunes

around in her head for a long time before finding a way to give them form.

For her, abstraction was a clarifying order of interlocking rectangles,

horizontal stripes, lumbering squares and powerful wedges.

Her color choices leaned toward the bracing. Yellows tunnel through

whites and hang over orange. Her blacks shine, and her blues are deep

as the sea.

Irregular yellow bands might pop out against flat blacks and sturdy blues in a small drawing. Working larger, long verticals might shore up fat, faintly irregularly horizontals. Curves and half-circles rest in the austerity of right angles. One can almost hear the “click” as a curve slides firmly into place.

Living most of her life in the countryside, her paintings have an urban edge. They are shocks to the system, siren calls to experience the world anew.

For many years, however, these siren songs were sung in secret.

Art is something of a team sport, in that artists tend to thrive when keeping close company with other artists. Through discussion and example, they challenge, affirm and advance each other’s ideas.

Henry, in contrast, has always been a bit of an art-world loner.

She was the fourth of six children born in the mountains of Sonoma County, Calif., near a quicksilver mine where her parents worked.

My parents were good people, but they had no sense of beauty. That was my interest from the beginning. I was still small when my brother married. My sister-in-law brought something new to our house. She cut flowers and arranged them on a table. She gave me a sense of what a room could look like if somebody tried to make it pleasing. Once, as a present, she made me a water lily out of crepe paper. I kept it for years.

After high school, Henry spent a year as a mother’s helper, getting together the money to go to college.

I don’t know what the mother did, because I did everything. I hated it, being a servant.

Determined to be an artist, she attended the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, earning a bachelor of fine arts degree in 1938. She married in 1943 and had two children, a daughter in 1944 and a son in 1947. She became the family’s chief breadwinner by specializing in industrial design for corporate headquarters, but longed to be painting.

My husband was Cary Grant-good-looking, but he never found himself, even though he graduated from Stanford, quite an accomplishment in those days. As a father, he was a bit of a Victorian. After a while, I lost respect for him.

She stayed married until her daughter was in college and her son in high school. In 1964, she made the break, buying a house in Mendocino after the divorce.

By the late 1960s, the hippies had arrived.

I loved them. I’d have parties, 150 people a night, always with music. The Rolling Stones were my favorites, also Bob Dylan and Cream. It was a good time to be alive. People who were young then were very accepting. They never treated me as if I were an old lady, but I must have been, to them. Eventually, they decided they had to earn a living. The place changed. There were more tourists than locals. I didn’t feel at home anymore.

She had another reason for making a change: her art career was going nowhere. Although she knew people whom she felt were creative in Mendocino, she didn’t know any other serious painters. It was an artist colony that lacked committed artists. Being one, she was odd man out.

In 1976 she chose Seattle, partly because her only surviving child, daughter Suzanne, lived there. (Henry’s son was killed years earlier by a drunken driver.) But Instead of living in the city, she bought property on Whidbey Island.

It was remote but ugly, not likely to draw tourists.

From her point of view, its overall ugliness made it the perfect place to create a haven of private beauty.

Finding a gallery to show her paintings wasn’t easy.

I think a lot of gallery owners at that time would look at me and think I was too old to be interesting. And my paintings were hard. Abstraction isn’t easy to like. People have to develop a taste for it, and why should they, when there are so many other kinds of art out there.

Asked how she managed to keep painting in spite of years of neglect, she chuckled.

It’s what I do. If I were a writer, I’d write and wouldn’t stop just because nobody read me. Art is part of my life. In two years, I’ll be 90. Then I’ll be old. Until I can’t, I’m going to continue to do what I’ve always done, though at a slower pace.

Living alone left room for indulgence. Waking early, she’d make herself a “home-made latte” (hot milk and instant coffee) and retired to bed to drink it while reading.

She favored mysteries, especially the English ones, such as Dorothy Sayers, but also kept up with art books and journals. She got up when she felt like it and listened to a classical radio station from Canada that has no advertising.

In the summer of 2001, she tended to cut short her reading in order to be out in the garden, killing caterpillars.

There’s an infestation every seven years. Look at that apple tree. They’ve eaten all the leaves. I drown them, step on them and use organic spray. I try to give up and live with them, but every seven years, I’m out here, killing as many as I can.

Standing beside her, I saw two caterpillars climbed over each other in slow haste, heading toward new green shoots on a rose bush. She turned away and shrugged, tucking a strand of wild, white hair behind her ear.

I guess you could say in my life I’ve been left to my own devices. I knew what I wanted to do, and that’s exactly what I’m doing.

A beautiful woman and for those Artists who age and mature outside the loop an inspiration.

This is a wonderful article. You have described Mary so well. I admired Mary’s absolute clarity of purpose in her art and life.

When Lauri Chambers introduced me to Mary, Mary told me that she didn’t have representation and that she was building a new studio at 84 years old. While standing in front of a beautiful, big painting by Mary, I told her I would give her a show. She never exhibited shock at what a small space PDX was at that time, but she must have wondered. With that casual beginning we were off to a fine association.

Mary’s current show at PDX Contemporary Art will be up through Sat May 30th. It is nice knowing that she was able to be at home until the end and that she knew her work was being exhibited.

Thank you for this, Regina. Billy alerted me to Mary’s death and I knew you’d write something fine.

Her work was transcendent…no it wasn’t…it was tough and real, like her–and beautiful, like her. Her work was a tutorial into art history that jumped off the canvas (or paper…those little colored-pencil sketches?! brilliant) and insinuated itself into your eye/brain but also remained, obdurately, but delicately, an art object. I’m so happy that I knew her and so proud to say that I got to organize an exhibition of her work.

I can’t say “I’m thinking of you Mary wherever you are” because I think that when people die they die; this one hurts because despite her age I really always thought I’d see her again. Also, and, sure, this is inappropriate, but what the hell, smoking pot with Mary was a total hoot.

Brian

She will be missed by this painter, she was, along with many others locally, an inspiration for me to do the work I wanted to do, and work I believed in strongly, she was something very special and the work was always on point, strong, bold, and inspiring.

I really enjoyed this article. Mary must have been a wonderful woman. I wish I could hve met her. As I am 66 years old and a woman artist, this story really rang true for me. I was the eldest of four children , born in Washington state. I have been able to pursue my career in spite of my family’s lack of encouragment.

I too gardern and love turning blight into eden.

Unlike Mary, I paint landscapes and wildlife in great detail. Still, I appreciate Mary’s art. I am glad she lived her life her way.

Thank you for this article.

Best regards,

Jacquie Vaux

http://www.jacquievauxart.com

What an incredible woman. I am grateful for her vision and life. It inspires me. She is my new hero.

I gave Mary her first Seattle show of her drawings,

She represented to me the best of the arts experience.

She was always as sharp as a tac, always moving forward.

Thank you for this post. Mary Henry has such a strong and rooted voluptuary and ascetic dialogue going. It is those contraditctions (?) that keep me coming back for more. But I would ask you to elaborate because I don’t understand what do you mean by “bright yet sour tonalities”?

Tough. The opposite of seductive. They lead with a twang.

What a great piece – thoroughly engaging and educational, inspiring and deep while inviting me further into an understanding of this terrific woman, human, artist. It’s not every day you read an art piece that is a piece of art itself. Thank you! Erin

I knew Mary for the last two years of her life I saw her weekly and helped here when she was in need…What a wonderful woman. All I knewn about her was that she was a painter and I admired her many paintings hanging on the walls of her home…now I know who she truly was, she was more then just a painter…thank you for sharing and she will be missed by all.