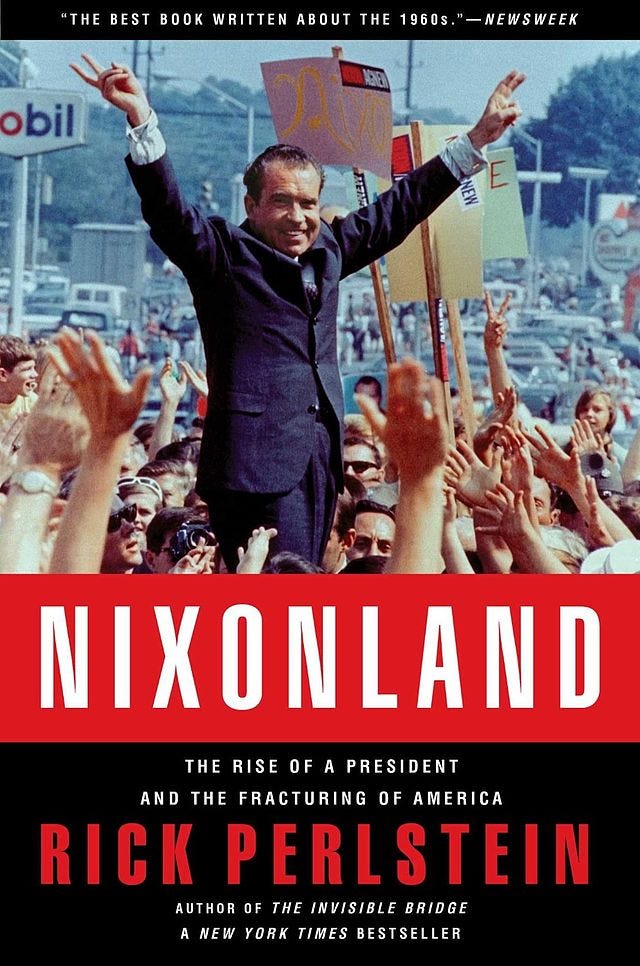

(January 24, 1970, Richard Nixon in Philadelphia to present the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Eugene Ormandy: AP photo).

A few days ago I wrote about a post by Thomas Wolf on public arts support in the US – I focused on what he said about the income tax deduction for charitable donations as an “indirect” arts policy. Not to get all obsessive about his post (most of which is unobjectionable!) there was one more thing that struck me. He wrote:

In 1977, the U.S. Congress’s appropriation for the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) reached $99.9 million. The growth in federal dollars had been extraordinary since the earliest days of the NEA when, in 1966, the appropriation stood at $2.9 million. Every President—Democrat and Republican—since 1966 had proposed funding increases to the agency, with some of those increases, including those of President Richard Nixon (hardly an arts enthusiast), being quite dramatic.

This is not about to be a defense of the presidency of Richard Nixon. His political methods haunt us to this day – I cannot recommend Rick Perlstein highly enough.

But … he actually was an arts enthusiast. He played piano and violin, enjoyed playing for others, and is one of the few modern presidents (I’m guessing here) to have composed a piano concerto – he performs it here, as a bit of a lark, in 1962 on the Jack Paar show:

Edward Allan Faine writes:

By his own admission, and attested to by others, Nixon was a classical music devotee. [Moreover, and] no doubt influenced by his early training on violin and piano, his ardor extended to light or semi-classical (Mantovani, Boston Pops, and 1001 Strings) and musical soundtracks (Gone with the Wind, My Fair Lady, Carousel, Oklahoma, and King and I) . . . Nixon told Washington National Symphony conductor Antal Dorati that his favorite composition was the background music by Richard Rodgers for the motion picture Victory at Sea.

And Duke Ellington recalled:

While taking us around various rooms on the family’s floor, he led us into one where there was an expensive stereo machine with many records and tapes. He proceeded to demonstrate all the audio possibilities—increasing the bass and the treble, one after the other, and showing how well the range was maintained at full and low volume. He was just like a kid with a new toy.

Is Nixon’s piano concerto very good? Not really, though I say this as someone who has never tried to compose one himself. Is his taste in music highbrow? No.

Was he an arts enthusiast? By any reasonable measure, yes, he was. My understanding is that he did not come to this through any inheritance of cultural capital, as the sociologists put it. It was not for show. It is not surprising in the least that he approved of great increases (greater than any other president, I believe) to the National Endowment for the Arts

Orchestra managers, opera company fundraisers, art museum curators, grants-agency administrators: the Trump voters walk among you. They go to your concerts, they come to your museum exhibitions, many of them know an awful lot about music and painting, and might so value your institution that they donate pots of money to you. Assuming that political views different from your own mean they could not possibly be arts enthusiasts – as Wolf seems to do here – is mistaken. The twentieth century gave us more lessons than we needed that there are no straight lines between political views and taste in the arts, any more than there are straight lines between taste in the arts and being a good and generous person privately. Don’t assume.

Cross-posted at Substack: https://michaelrushton.substack.com/

Excellent point, well made.

Thanks Margy.

Hi Michael,

Thought-provoking, as always. Discourse on your observation might lead to questions of whether the arts, then, are to remain politically neutral and, some might say, diligently conservative so as not to offend. Will works that deal with challenging social issues, dilemmas of trans and LGBTQ populations, threats to democracy, or environmental justice be censored so as not to lose donations from politically conservative, even Trump supporting audiences and donors? A classical pianist friend who is an avid Trump supporter and a native Russian believes there is no place in “serious” music for expression of, or commentary on, many of the social issues that divide us between liberal and conservative perspectives. He does not believe that DEI should enter into hiring decisions about artists or administrators, or the selection of board members. While it is true that conservative ideologists may be lovers and aficionados of what they consider “high” art, or art worth supporting financially, is it also true that succumbing to such ideology for the sake of audience numbers and dollars could render the arts impotent of their inherent value in contributing to a more just, equitable, and progressive society?

David, thank you for your comment. I think, again, we need to be careful of assuming dichotomies that are not so simple. So, while there are certainly people with very conservative (or Trumpist, which I consider a different thing) political views who do not enjoy seeing art that is overtly political – this is the editorial stance of The New Criterion, for example – it is also the case that there might be people who hold generally progressive political views – let’s have universal health insurance, progressive taxes, environmental protection, and live-and-let-live with respect to LGBTQ people – who also do not find a lot of value in art that is overtly political. Into that latter camp I would put myself.

Will arts organizations make aesthetic choices based on politically conservative funders? Maybe. But arts organizations can, and do, also chase money by explicitly pursuing environmental – https://www.giarts.org/article/funding-intersection-art-and-environment-field-scan – or other progressive – https://www.mellon.org/grant-programs/arts-and-culture – causes. To my mind everything starts to go awry when arts presenters make choices about their art based upon the perceived politics of their source of funds, right or left, or of protests of what they want to do, again from the right or the left: https://michaelrushton.substack.com/p/arts-presenters-need-to-show-some

I do not believe that the arts have an inherent value in promoting a more just, equitable, and progressive society. I recognize that reasonable people can disagree about that, but it is worth keeping in mind that not everyone sees the arts through a social justice lens, even people who would like to see a more equal society.

The point of my piece is to not assume, not to see the art world in terms of two sides.

Just a brief further thought, Michael. My experience on numerous arts boards populated by mostly fiscally conservative business people (I myself am fiscally conservative, I might add, but not from the corporate perspective) has been to observe that risk aversion is a common perspective, largely due to the fear of losing funds. As we know, foundations are decreasingly interested in arts support, resulting in a drive to gain private funding. As we also know, today’s funders are more inclined to expect something in return rather than to give for the simple cause of a greater good or a better quality of life. I do disagree that there is no inherent value in art (as process, not object) for equity and justice. It is true that Trumpism and conservatism are different, but Trump has commandeered a once conservative party into presumably representing today’s conservative perspectives. What concerns me is the inhibition of free expression, i.e., a “liberal” perspective in the best sense of the word, according to ideologies meant to control rather than encourage discourse and dialgoue about meaning and value, a la Roger Scruton, for example.