In the New York Times, Isaac Butler sounds the alarm for the fate of live theatre in the US:

The American theater is on the verge of collapse. …

Regional and nonprofit theaters were in trouble well before 2020 and the force majeure of the pandemic. Most regional and nonprofit theaters were built on a subscription model, in which loyal patrons paid for a full season of tickets upfront. Foundation grants, donations and single ticket sales made up the balance of the budgets.

For much of the 20th century, this model worked. It locked in money and audiences, mitigated the risk of new or experimental shows and cultivated a dedicated base of enthusiasts. But this model has been withering for the entire 21st century. Subscriber numbers are falling, and nothing has arisen to take the place of that revenue or that audience. Not surprisingly, ticket prices have gotten higher, making new audiences more challenging to find.

This smoldering crisis was exacerbated by the pandemic, a ruinous event that has closed theaters, broken the theatergoing habit for audiences and led to a calamitous increase in costs at a moment when they can least be absorbed. A collapse in the nonprofit sector doesn’t just mean fewer theaters and fewer shows across the country; it also means less ambitious work, fewer risks taken and smaller casts. The reverberations will be felt up and down the theatrical chain, and a new generation of talent will be neglected. As with a bank collapse, in which a few foundering institutions can bring down a whole system, the entire ecosystem of American theater is imperiled. And American theater is too important to fail.

His solution? A federal government bailout, similar to how it has in past decades bailed out banks and the automobile industry (neither of which was without controversy and dissent).

He cites the Federal Theatre Project from the Great Depression as a model, and I wish arts commentators would stop citing a program from nine decades ago that was meant to solve a problem of widespread and devastating economic depression and unemployment with the main goal of simply getting people to some sort, any sort, of job. The current US unemployment rate is 3.6%.

He also thinks the National Endowment for the Arts could use a boost in funding, and, sure, but that is hardly going to turn around, or even make much of a dent, in the finances of live theatre.

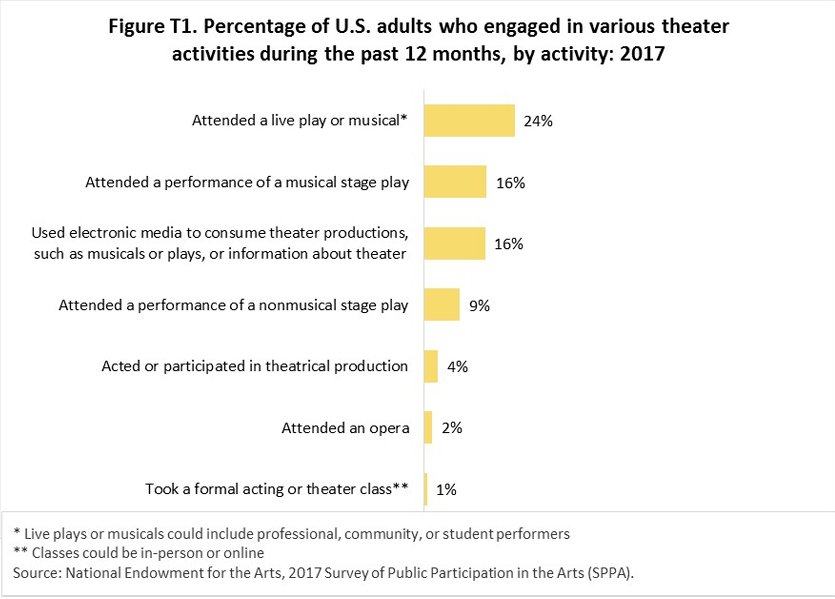

But here is what he does not mention: audiences. Let’s go to the pre-pandemic 2017 NEA Survey of Public Participation in the Arts. In that year, 9% of US adults attended a nonmusical live stage play. The numbers break down to rates of 10% for urban residents (who would have better access to live theatre) and 6% for rural.

Here is the real difficulty in talking about how to “bail out” theatre, and it goes beyond the decline in people opting for subscriptions, or the perpetual march of cost disease in the live performing arts. You cannot save an art form if people are not interested in attending. Nor can you easily call for an infusion of public funds into subsidizing such a minority taste (and what tends to be a rather well-off minority at that). Theatre, orchestral music, opera, ballet, need an interested and knowledgeable (if not connoisseur-level) cohort of people who make a point of getting out of the house, with all of its attractions of quality big-screens and sound systems, to attend a live show. The problem is us.

Footnote: this was noted a long time ago.

Thank you, Michael! As always, I enjoy reading your perspective on these topics.

I also read a resistance to change in the article that really concerns me. Lamenting the loss of the subscription model ,which I hypothesize never really rebounded from 9/11 or the way things “used to be” isn’t helpful. If the government were to support theatre, and nonprofit culture broadly, in the ways Butler (2023) argued, what changes will theatre make in return? I ask because the US creative sector has yet to actualize the access, diversity, equity, inclusion, multiculturalism, and pluralism explicitly and implicitly suggested in the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act of 1965. Gilmore (1993), Sidford (2011), and Helicon Collaborative (2017) alerted us to the fact that most of the cultural funding has gone and continues to go to the predominantly White serving cultural organizations entrenching deep cultural inequities to the detriment to global majority cultural organizations who still find ways to do amazing work. And yes, I’m aware of the Wallace Foundation’s $100 million investment on researching global majority cultural organizations, but how does that make up for years of disinvestment and address the potentiality of it in the future? Theatre and the whole of the creative sector should explore for-profit entertainment + nonprofit partnerships as Ivey (1999) and Wilkerson (2012) suggested. For example, why doesn’t for-profit theatre donate a % of its earnings to non-profit theaters? Or does it? It seems that the flow of cash could help abate the demise of theaters that test the content that goes to broadway and tour the globe. Second, the creative sector needs to adopt an ethos and practice of anti-oppression. People with disabilities, people of the global majority, LGBTQIAS+ folx, nonbinary & women, and poor people all have buying power in our society which theatre could have more access to if we stop “playing” access, diversity, equity, and inclusion (ADEI) and start “living it” as Jackson (2021) argued. Lastly, a recent study from researchers at the Brookings Institute found that racial and ethnic inequality has cost the US economy $51 trillion since 1990. Can theatre, the creative sector, and the US really afford to be racist?

TRANSLATION FROM LEFTSPEAK:

Rich people like to go to the theater on occasion, but they want their theater to insult the bourgeois scum who do all the work. They also don’t want to pay for it. Time then for the government to squeeze more tax revenue out of the bourgeois working class scum to pay for the American theater, and to thus make sure to keep that bourgeois scum out of the audience as well, by not letting the American theater be forced to cater to commoners buying tickets as in the bad old days.

But the point of England (and other countries) supporting the arts and artists financially is well-taken. Performing arts (with the exception perhaps of large scale commercial hits in big cities) have always required subsidy of one form or another: fundraising, grants, sponsorships, low- and unpaid labor, affiliation with an educational institution, use of free or low-cost civic performance spaces, etc. Robust support like Europe will probably never happen in the US— but there’s an argument to be made that if the performing arts weren’t so dependent on ticket sales and fundraising from the elite white attendee base, they might be able to present work that is compelling to a wider variety of people,

It seems to me that that there is an omnipresent assumption that “white people” form an elite with art interests that others can’t, won’t, or don’t share. If we believe that high art has a universal value, why do we insist on saying people who aren’t white won’t be interested in it?

My family was lower middle class when I was a kid, but I had access to classical music on the radio, an infinite number of books in the library, cheap seats in theaters, and so on. Some of my friends shared this interest, many others didn’t–but it wasn’t a function of our skin color or our economic class.

I agree with you. I grew up in a working class Chicago neighborhood in the 1950s. But you could walk down the street on a summer Saturday afternoon and hear the Met Opera or the Cubs game on an equal basis. High mass in the myriad Catholic churches were music, pomp, and like a theatrical production. The local branch of the Chicago Public Library was accessible by myself when I was a youth, and its shelves and books held mystery and awe. Museums were free. And in school we had music, art, and theater. We were introduced to and experienced culture.

The for-profit music industry is corporate, and makes money with formulaic performances that reflect what the public is propagandized (through social media and expensive major media) to buy.

Because non-profit music makers simply don’t have millions to buy advertising, the giant rift exists.

Also, one point that needs to be made is that the US capitalises on American music, starting with jazz, leading to rock & roll, pop music, etc. Europe, on the other hand, supports all the music that was conceived for centuries on that continent. Europeans own it; therefore, they are willing to support it.

Where is an American airport that bears the name of a great American composer, author, or artist? Warsaw’s airport is Chopin, Budapest’s is Franz Liszt, and Rome’s is Leonardo da Vinci. When will someone name one of New York’s airports after Leonard Bernstein?

Dear Michael, I was thrilled by the article many thanks, although I believe some more multidimensional perspectives are needed as we need to be extremely careful when throwing out the idea and notion of minorities being interested in theater (9%).

Although the number is low, allow me to give a perspective from South America, where the funding model always has depended on the notion of public subsidy (whether we can question if this is a good idea or not, let’s get into that later…).

Public money does not always stand in the premises of market share, return on investment, and if this should go to the masses or the minorities. Public money is there for precisely that, invest where no one el would, based on the idea that culture and the arts are a public good, with proven external spill-over effects. Thus, supporting that 9% who attend, probably will disseminate in a larger group of indirect beneficiaries.

Moreover, the relevant measurement is not based on that 9%, the perspective of public support should be measuring how that number will grow through the years, proving the relevance of public policies for the arts.

Greetings from the south, please let me know if you want the conversation to continue!

Over three decades ago when I was director of external affairs for the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, I attended a meeting at which the main speaker was a marketing expert–not an arts marketing expert. The audience was expectant to get new insights, the next great idea to build an audience. The speaker (and I wish I could remember his name) spent the first 30 minutes criticizing us. He said that we spend all our limited marketing dollars on renewing subscribers and wonder why we have little money to expand our audiences. He showed examples of the expensive booklets we send to subscribers and donors to sell subscription tix, and the cheap looking postcards we use to sell single tickets. We expend our money and efforts on a small subset of our potential audience and then wonder why we can’t grow our audience. I have always taken his words to heart.

Michael: I’m with you completely on the futility of trying to make the case foe a federal bailout. Mr. Butler makes an eloquent case and it’s difficult to disagree with his characterization of the benefits. But there’s a less than zero chance politically of such an action by the US Congress. And besides – such a “bailout” doesn’t solve the underlying problems.

I do think it’s problematic these days to talk about audience size as proof of anything. There are plenty of YouTube videos that have hundreds of millions of views but failed to earn sufficient revenue to support their artists. Musicians can have huge audiences online and fail to earn enough to support themselves. The problem is that compensation has been separated from the measures of consumption. Further – consumption (or copies sold) has never been a good measure of the value of art. In the age of cultural abundance, the audiences have never been bigger, their consumption has never been higher. But algorithmic boost has distorted the meaning of an audience that scales. The lack of engagement with theatre has many causes. But it may also mean that the infrastructure that puts theatre in the path of potential audience has been busted (rather than anything theatre itself is or isn’t doing).

Doug: I agree with you that audience size proves little, especially in this age of cheap digital abundance (maybe I have missed it, but is there a leader of a publicly funded arts council in the US willing to publicly and forcefully say so?). My point is that live performing arts need live audience. The audience might not be large, it might be rather niche, but people need to show up for the aesthetic and social experience that is live performance, if live performance is to continue to survive, especially outside of major cultural capitals, and this is true for nonprofit as well as commercial arts (a distinction that tends to be much overdrawn – there is innovative and experimental commercial art, and banal, tired nonprofit art). There is no change in means of funding that can get around this, no federal or state or foundation money that can save live performance without this.

The neoliberal paradigm of small government: Starve the arts so that they can’t build audiences, then say the starvation is justified because few are interested in the arts. (And while we’re at it, let’s make government so small we can drown it in a bathtub.)