When arts presenters set prices, they know that there are some customers willing to pay top dollar for the highest quality offerings – the best seats in the house – while there are other potential customers who might have an interest in attending the show, but only at a lower price.

The challenge in setting prices for different quality seats is that while we know there are different sorts of customers, some willing to pay a lot for high quality and others who are not, when a person comes to the box office window we cannot tell what sort of customer they are. Direct price discrimination is where people belonging to different groups are offered different prices on the basis of who they are – student and senior discounts are an example. But that is a blunt instrument, and doesn’t give much scope for really differentiating those willing to pay a lot from those only willing to pay a little.

The solution is to set a “menu” of prices, and let each person choose what price/quality option they prefer – this is known as indirect price discrimination. In this way, the presenter is able to get a high price out of those willing to pay it, while still filling what would otherwise be empty seats with lower-priced offerings. In this “scaling the house”, the rule of thumb is to find the sweet spot of a price differential that separates the customers. Make the price difference too high relative to the quality difference, and no one will buy the high-priced option. If you are going to charge differential prices at your theatre hall, or baseball stadium, or airline tickets, there has to be a real difference in seat quality (or leg room).

Sometimes presenters will create a quality difference by deliberately lowering the quality of the low-priced version: there is a reason you have to wait a bit more than a year to get a hold of a paperback version of that new bestseller. Publishers separate buyers who really want this new book *right now* and will buy the hardcover version, and those who only want to pay paperback prices – the latter have to wait.

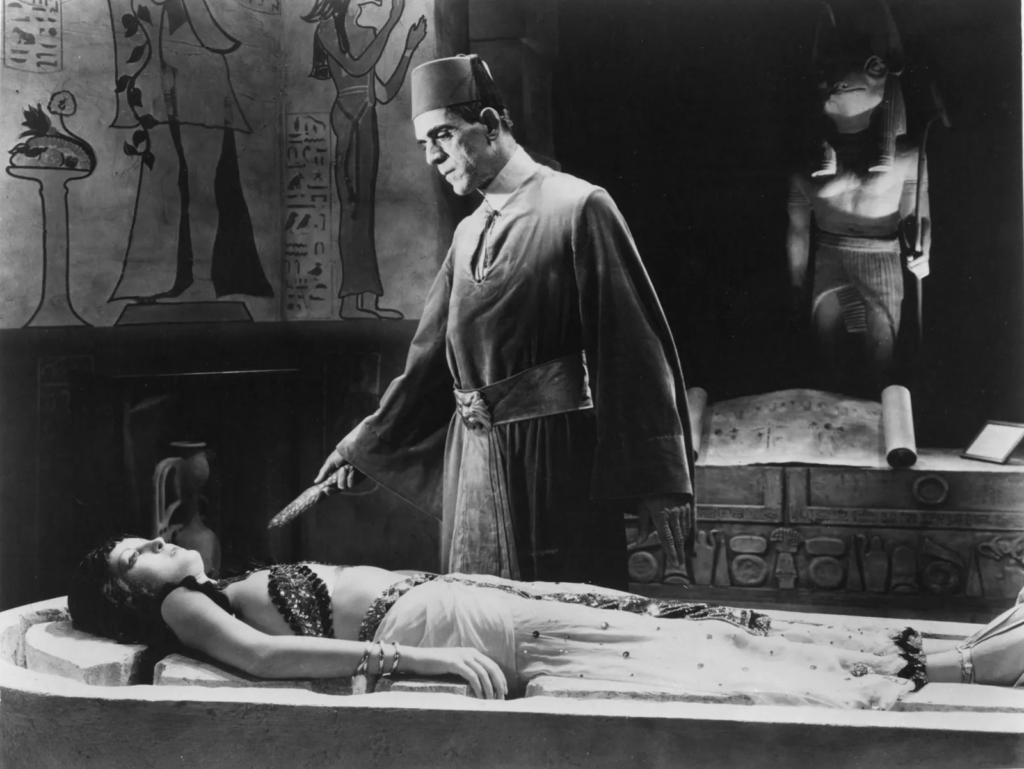

And so … on to the question of mummies.

My summer reading is an old Penguin Classics version of Herodotus’s The Histories, written sometime around 450 – 440 BC. It concerns the wars between Persia and Greece, with a lot of backstory. In Book 2 Herodotus travels to Egypt, and gives an account of its history (based upon what people tell him), traditions and social life (note this is all before the Macedonian invasion of Egypt in 332 BC, which is a part of the Egyptian story currently salient in the arts world).

In sections 86 and 87 of Book 2, he describes the process of mummification. Not just the physical process, but its pricing on the basis of quality options. Here are the translations by A.D. Godley from 1920 (my Penguin version is, as Penguins always are, more colloquial, not being designed for the classics scholar):

There are men whose sole business this is and who have this special craft. When a dead body is brought to them, they show those who brought it wooden models of corpses, painted likenesses; the most perfect way of embalming belongs, they say, to One whose name it would be impious for me to mention in treating such a matter; the second way, which they show, is less perfect than the first, and cheaper; and the third is the least costly of all. Having shown these, they ask those who brought the body in which way they desire to have it prepared. Having agreed on a price, the bearers go away, and the workmen, left alone in their place, embalm the body. If they do this in the most perfect way, they first draw out part of the brain through the nostrils with an iron hook, and inject certain drugs into the rest. Then, making a cut near the flank with a sharp knife of Ethiopian stone, they take out all the intestines, and clean the belly, rinsing it with palm wine and bruised spices; they sew it up again after filling the belly with pure ground myrrh and casia and any other spices, except frankincense. After doing this, they conceal the body for seventy days, embalmed in saltpetre; no longer time is allowed for the embalming; and when the seventy days have passed, they wash the body and wrap the whole of it in bandages of fine linen cloth, anointed with gum, which the Egyptians mostly use instead of glue; then they give the dead man back to his friends. These make a hollow wooden figure like a man, in which they enclose the corpse, shut it up, and keep it safe in a coffin-chamber, placed erect against a wall.

That is how they prepare the dead in the most costly way; those who want the middle way and shun the costly, they prepare as follows. The embalmers charge their syringes with cedar oil and fill the belly of the dead man with it, without making a cut or removing the intestines, but injecting the fluid through the anus and preventing it from running out; then they embalm the body for the appointed days; on the last day they drain the belly of the cedar oil which they put in before. It has such great power as to bring out with it the internal organs and intestines all dissolved; meanwhile, the flesh is eaten away by the saltpetre, and in the end nothing is left of the body but hide and bones. Then the embalmers give back the dead body with no more ado.

The key to indirect price discrimination is to give options from which the customer can choose, and that is what is going on here: “Could I interest you in our ground myrrh package?” Adam Smith claimed part of human nature was our “propensity to truck, barter and exchange.” So is strategic pricing, I guess.

Leave a Reply