There are two ways to approach equity, which I’m going to define as a fair or just set of entitlements or outcomes among people, not necessarily equal, but fair.

One way is to focus on people’s disposable income: what are people able to buy for themselves? How they spend their money is not the primary concern. If you and I have equal disposable income, and face the same prices when we shop, what does it matter if you spend more on rent and less on going out than I do, if we each have the same options? There are some economists, typically libertarian-ish, who think we should keep our focus on income distribution, using progressive taxation and transfers to make it somewhat more equal than what the market generates, and then leave it up to people themselves to decide what to consume.

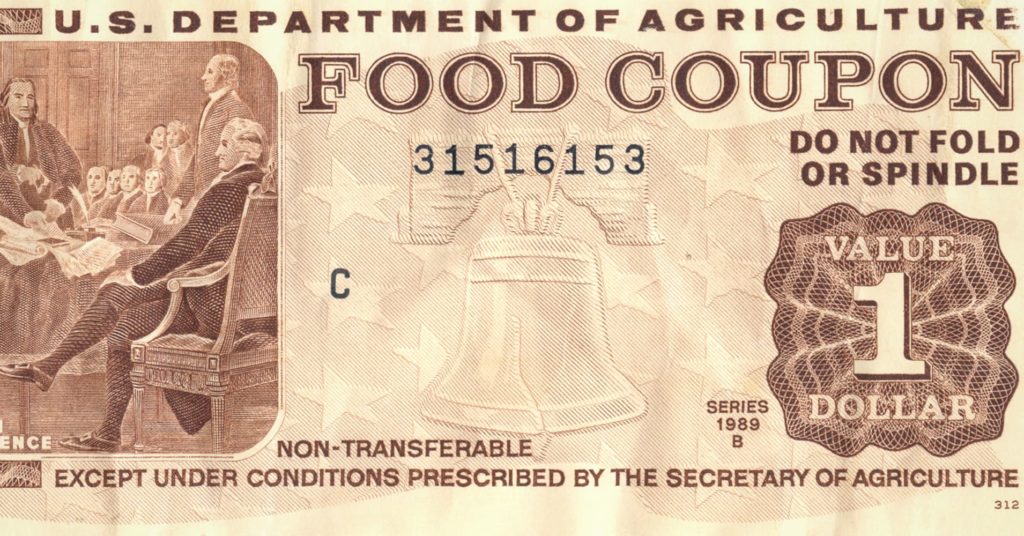

And yet, there is another way to approach equity, more prevalent I would say, that holds that what specific things we consume matters. In the US we transfer resources to low-income people through food stamps, which not only must be used on food but must be used on particular types of food (a policy I find appallingly patronizing), and we subsidize rents. There is consensus that as health care is (literally) vital, and can be catastrophically expensive in a free market, there ought to be policies that ensure the poor will receive care they need. Public education is justified on the grounds that this particular good ought to be available to all. We have other policies where we insist on equality. In an election each citizen gets one and only one vote, which cannot be bought or sold. One cannot buy their way out of national service – in her terrific book on the origins of his Theory of Justice, Kat Forrester recounts how political philosopher John Rawls went against the vast majority of his Harvard colleagues in opposing educational deferments from the draft during the Vietnam War, seeing an unjust inequality. In times of crisis, a war or a natural disaster, there are calls for rationing of essential goods, not leaving their allocation to be determined by market prices alone.

James Tobin wrote a nice short (low tech) essay on this in 1970, “On Limiting the Domain of Inequality” where he goes through a number of examples of the sort above. The limits in question are around what goods are ones where we believe equity requires specific intervention in those goods, and what are goods that we can simply leave to the market, assuming we have done right in working towards a reasonably just distribution of purchasing power.

He writes:

The social conscience is more offended by severe inequality in nutrition and basic shelter, or in access to medical care and legal assistance, than by inequality in automobiles, books, clothes, furniture, boats.

He suggests leaving “non-essential luxuries and amenities” to the market. But that leaves the question: what are we going to call non-essential? If we think “the arts” ought to be a good where the market distribution is not acceptable, what specifically do we mean by “the arts”, especially in a world where people will have widely divergent tastes and interests?

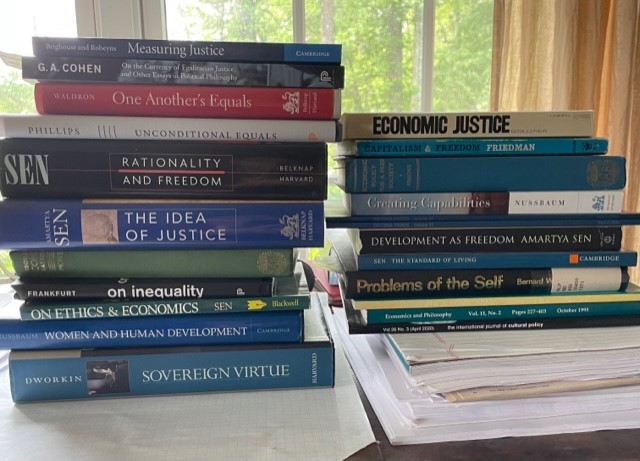

I’ve some reading to do…

Suggestions to add to the pile are very welcome…

Leave a Reply