In the field of cultural affairs I often come across papers that use the word “neoliberalism”, virtually always describing a bad thing, but with its precise meaning pretty vague – even when I ask as a friendly question what the presenters mean they are not quite sure. In arts policy, it is often applied to criticism of cuts in funding, though neoliberalism doesn’t seem to apply to all cuts in public budgets – you don’t typically see someone calling for cuts to the defense budget referred to as neoliberal.

So here I’m going to take a stab at what I think it might mean – your comments are very welcome!

In my last post I talked about Econ 101ism. Let’s dig into it a bit deeper. The first fundamental theorem of welfare economics holds that an economy with competitive markets, a complete set of markets, and full information, will generate an outcome that is Pareto efficient. Breaking it down into parts:

- Competitive markets have many buyers and many sellers, none of which is big enough to be able to influence prices by their behavior;

- Complete markets means that there are ways of organizing transactions in all possible goods and services, now and in futures markets (this turns out to be really important for arts subsidies…)

- Full information means that everybody understands fully what they are buying and selling, they are aware of all prices;

- Pareto efficient means that with this outcome, there is no possible rearrangement that could make someone better off without at the same time making at least one person worse off, where “better off” and “worse off” are in the eyes of the individuals themselves.

This result is a limited one. Market failures, either through lack of competition, lack of complete information, or simply the lack of a market at all, are commonplace in the real world. And a Pareto efficient outcome could be one with tremendous inequality of welfare.

And yet at the same time the result is rather amazing. Buyers and sellers out and about pursuing their own interests (which need not be selfish ones), without any authority ordering them to buy more of this and less of that, to grow more rye and less wheat, are led as if by an invisible hand to generate an outcome with some degree of efficiency. If in my town of Bloomington the equilibrium competitive price for a basic haircut is $24, and about 21,000 haircuts are sold each month, there is no good reason for the state to question that outcome, to seek something different. In fact, this decentralized method of markets is the only way to reach such an efficient outcome, since there is no way a centrally planned economy could possibly accumulate, update, and process all the necessary information about consumer preferences in haircuts or in how many people are interested in working as a barber, and how many hours they would each like to work.

So why subsidize the arts? Aren’t there markets for concerts and films and paintings? For economists, the standard story is that there are market failures, mainly of two types.

The first is what we call public goods. Economists have a very particular way of defining this: it means goods that are (1) non-rival – once provided to the public, any extra users do not diminish the benefits to anyone else enjoying the good, and (2) non-exclusive – once provided to the public, there is no practical way to keep people from enjoying the good, no feasible way to set up gates and a ticket booth. Public art generally fits this bill – sculpture and murals and other installations. My pausing to enjoy a work doesn’t block anyone else from doing the same at the same time, and it would be pretty impractical to try to sell tickets. We could also add non-commercial public broadcast radio to the list of public goods. (Non-arts examples would be national defense, city streets and streetlights and sidewalks, small urban parks, etc). No one except for charity has reason to provide such goods – there’s no way to collect revenue. Markets do not work well here, and if people want public art they can persuade the government to use some tax money for that purpose.

The second would be what we call externalities. Here, there are activities that generate benefits and costs to individuals but not through any market transactions. A noisy leaf-blower in my neighborhood imposes a cost on me for which I am not compensated – my peace and quiet have simply been taken from me. Someone else in my neighborhood tends carefully to make a beautiful garden that I enjoy each time I walk by, yet they are not compensated by me for this benefit. There are costs from negative externalities and benefits from positive ones, yet no market for them. This causes negative externalities to be over-produced (the man with the leaf-blower bears no personal cost for the costs he imposes on me) and positive externalities to be under-produced (there is no market compensation for producing things that benefit strangers). That the arts might have many positive externalities is the primary reason economists working in the arts have argued for subsidy: the artists and arts presenters in my city, my country, the world, produce many good things even for the people who do not themselves attend the galleries and concerts. There is a market failure in these positive benefits, in that there is no market at all – it would simply be far too difficult to organize (our term in the trade for this is transaction costs).

In future posts I will delve into the externality question in the arts: what are they, precisely?

So, now I will give a try at defining neoliberal: a neoliberal takes the above as the basic framework for analyzing public policy. The neoliberal holds (1) the economic method is the best way to conceptualize policy problems, (2) that markets are very good at allocating resources efficiently without the need for government intervention, and (3) that if there is to be an intervention – a special tax, a subsidy, a regulation – it ought to be on the basis of a demonstrable market failure.

There’s a lot built into this: that people are the best judges of their own well-being – I’ll decide myself when it is time to get a haircut; that we should evaluate outcomes based on the well-being of individuals – there are no higher goods, there is no community well-being as anything more than the aggregate of individuals; that we begin the analysis with a decentralized market world, and then ask whether government has a role to play. There is a reason why the economic approach gets just one chapter in my book on The Moral Foundations of Public Funding for the Arts – it’s important, but it is but one way to approach the question.

All right, anyone who uses the word neoliberal in their work: have I missed something?

March 14 Update:

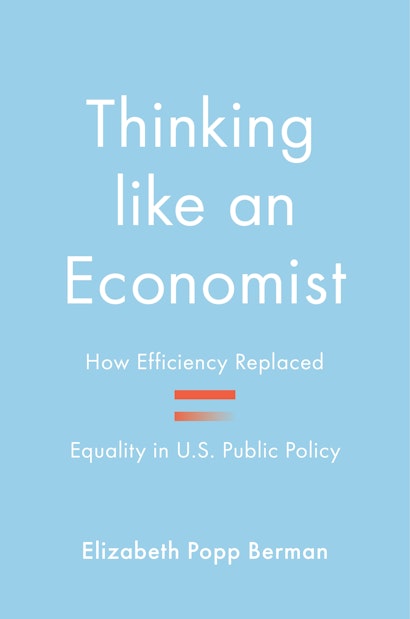

Elizabeth Popp Berman’s fascinating book describes the “economic style of reasoning” more or less as I did above. She does not reach for the term “neoliberal” however, since she associates that with a distinctively right-of-center political approach. But the economic style of reasoning is broader than that – from the mid 1960s through the mid 1980s, when it became firmly entrenched, it was center-left politicians and policy analysts as much as center-right that were conceptualizing market failures as the root of policy problems, market solutions as the way forward, and efficiency as the goal. Cap-and-trade programs for pollution reduction are a nice example of this way of thinking – create markets and generate incentives – rather than any non-economic reasoning about the moral demands of ecological harmony.

In arts funding, notice how much arts advocates focus on externalities as a rationale for funding: richer, healthier communities, better-educated children, etc…

Next entry in this series is here.

Neoliberalism holds that the market should be the ultimate arbiter of virtually all human endeavor. In the USA, far from feeling that interventionism should only be based on demonstrated need, neoliberalism is more absolutist and holds that there should never be interventionism. Did Milton Friedman or Friedrich Hayek write anything about the need for public arts funding? To what extent did they discuss of the limitations of the market in formulating social well-being?

People sometimes say the military is a neoliberal exception, but in reality it is a massively profitable industry and its domination of the government is a market force. Through salesmanship, which includes a massive lobby, it turns the government is a buyer. The government is a market too–an idea that neoliberalism doesn’t seem to address very well.

The fine arts in the USA are not a major market force and thus have little influence on the government as a market. The fine arts do not have an effective lobby. In much of Europe, by contrast, the government is a major buyer of fine art. This creates a lively market for the fine arts.

I think a discussion of neoliberalism and the arts would need to include the increasing resistance neoliberlism is facing around the world. It remains in force, however, because it is rarely instituted through democratic means.

Public art is not affected by supply and demand, but the performing arts are. There are 9 year-round opera houses within 90 minutes of where I live in Southern Germany. (Three are in Switzerland.) Even though all of the opera companies are owned and operated by the government, the best houses charge more for their tickets. That’s why I seldom see opera in Zurich even though its a great house. And it’s while I seldom see opera in Pforzheim. The tickets are amazingly low priced, but the productions not so great–even if I love that a city of 120,000 has a full time opera house. The locals don’t seem to mind the quality and the house is usually full.

Tickets for the Vienna Philharmonic in Vienna are usually sold out about ten years in advance. Supply is so short that tickets for the Vienna State Opera are often distributed by a lottery system.

In many opera houses in Germany, the houses could be almost always full, but the managers instead aim for an average 80% of capacity over the whole season. This allows them to occasionally program lesser known operas or new operas that might be less popular.

Hollywood, by contrast, knows only one criteria. Profit. We are thus inundated with movies about comic book heroes and the like. It pleases that IU frat boy who can chug three Buds and belch the entire Pledge of Allegiance. Weren’t Friedman and Hayek rather quiet about the cultural effects of pure market ideologies?

How is it that the EU, mainly through the Maastricht Treaty, effectively combined neoliberalism economic policies with social democracy and public arts funding?