Women pay more than men for some products. Why is this, and is this a situation where there oughtta be a law?

Women pay more than men for some products. Why is this, and is this a situation where there oughtta be a law?

Last week, Time reported that women consumers’ advocates in France were pressing for a law that would prohibit price discrimination where men and women use virtually the same product (razors, deodorant) but men typically pay less. Think Progress reports on complaints about gender-based price discrimination at Old Navy. And here is a longer report on the subject, from 2012, from Marie Claire.

A few thoughts (with the caveat that my thoughts on this are very much a work in progress – these are just some ideas):

- We can distinguish between direct price discrimination, where men and women are explicitly offered different prices, and indirect price discrimination, where men and women face the same menu of prices across items, but they tend to make different choices from within the menu, leading to different levels of payments.

- With indirect price discrimination, the goal is to discriminate between consumers with different willingness-to-pay, regardless of gender. In some cases this might lead to men paying more, or women paying more. So, for example, if there are some products for which men insist upon having the top-of-the-line model, even at a very high price (say, big-screen television sets), while women are content with a more modest flat-screen television, men will pay more (and pay a higher mark-up over cost), even though the goal of the seller is simply to target those with luxury tastes, not to target men specifically.

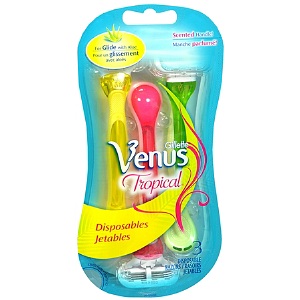

- Direct price discrimination between genders is done in an interesting way, and almost constitutes a middle ground between direct and indirect. Compare to commonly observed discount pricing for students and for seniors, while those in mid-life do not receive a discount. In this case the goods on offer to the groups are identical (admission to a museum, a seat for a performance, a buffet lunch) but some groups are offered a lower price. The rationale for doing so, from the seller’s viewpoint, is that students and seniors, on average, present different responsiveness to price than others – they are offered lower prices because their willingness-to-pay for the product is different, they are more price conscious. Now it might be the case that men and women have different price responsiveness to museum admissions or the cinema, but sellers are hesitant to adopt explicit discrimination where it would be deemed ‘unfair’, while discounts for students and seniors (or per-ticket discounts for families with children) are seen as acceptable. However, firms marketing products where they see differences in willingness-to-pay by gender can create market segmentation through the simple means of making some products the color blue and others the color pink. And it seems to work. If blue razors are identical to the pink, and the pink ones are priced higher (as the linked stories above seem to suggest), then women are not really paying a higher price for being women, but are paying a higher price for choosing the pink razors. With other products, differences in scent is used to segment the market, a slightly different situation, since scent is more ‘public’ (are unscented products sold at the same price?).

- Price discrimination based on market segmentation is also governed by competition. For clothing, for personal products, there are multiple sellers to choose from. A firm will not charge higher prices to women ‘just because’, since competing firms would attract sales by offering women lower prices. The differences we observe are based upon different willingness-to-pay, not from pure discrimination just for the sake of it (which would be unprofitable).

- Sometimes the costs of products are different, and this leads to differential prices. Women pay less for car insurance than men do, because they are less costly to insure: women are safer drivers. On clothing, while I’m no fashion expert (as my students, alas, will attest), it is true, as Old Navy claims, that men’s clothes are simpler, in the sense that we wear the same sorts of things regardless of body size and shape (a men’s suit is a men’s suit) while women’s fashions are more variable.

- The Marie Claire story suggests that women pay more where they do less market research, say in shopping for financial services (I have no idea whether this is true; it does not match my personal observations). But that is common in indirect price discrimination – it is always the case that less careful shoppers pay more, and firms are happy to exploit that within their own shop (grocery stores have multiple ways of charging more to the less careful shopper; cell phone plans on offer by a single seller are notorious for having good and bad options according to who bothers to read the details). As a consumer, if you want to avoid being on the wrong end of the stick when it comes to price discrimination, shop more carefully. Obvious, I know, but there are more savings to be had than you might realize.

Leave a Reply