Commercial or nonprofit? In studying the cultural sector one of the key questions asked is why we see both kinds of firms in the arts, where nonprofits are more concentrated in some sub-sectors than in others, and I pose the question to my students: how does an entrepreneur choose the organizational form for her new enterprise? Today in the Times we have an opinion piece by Jeremy Rifkin, ‘The Rise of Anti-Capitalism‘, who posits that the nonprofit sector is bound to rise in importance over the next few decades, not because of long-running trends but because of a significant transformation in how our economy will work. I confess, I don’t understand.

Commercial or nonprofit? In studying the cultural sector one of the key questions asked is why we see both kinds of firms in the arts, where nonprofits are more concentrated in some sub-sectors than in others, and I pose the question to my students: how does an entrepreneur choose the organizational form for her new enterprise? Today in the Times we have an opinion piece by Jeremy Rifkin, ‘The Rise of Anti-Capitalism‘, who posits that the nonprofit sector is bound to rise in importance over the next few decades, not because of long-running trends but because of a significant transformation in how our economy will work. I confess, I don’t understand.

He begins:

We are beginning to witness a paradox at the heart of capitalism, one that has propelled it to greatness but is now threatening its future: The inherent dynamism of competitive markets is bringing costs so far down that many goods and services are becoming nearly free, abundant, and no longer subject to market forces. While economists have always welcomed a reduction in marginal cost, they never anticipated the possibility of a technological revolution that might bring those costs to near zero.

Well, it is a good thing if the real costs of producing goods and services fall, on that point this economist is in full agreement. But low marginal costs [where marginal cost is defined as the cost of supplying one more unit of the good or service] do not mean that goods are ‘no longer subject to market forces.’ We have had, for a very long time, services supplied at virtually zero marginal cost. Museums and live performances that have some extra capacity for visitors can generally welcome them at zero marginal cost. Radio broadcasts can handle an increase in listeners at zero marginal cost. Libraries have virtually zero marginal costs. And none of these are new technologies.

The first inkling of the paradox came in 1999 when Napster, the music service, developed a network enabling millions of people to share music without paying the producers and artists, wreaking havoc on the music industry. Similar phenomena went on to severely disrupt the newspaper and book publishing industries. Consumers began sharing their own information and entertainment, via videos, audio and text, nearly free, bypassing the traditional markets altogether.

I don’t see how there is a ‘paradox’ here. There was sharing of entertainment goods (magazines and books and records) amongst friends before the internet, and technology has made it easier to share information and entertainment more widely, but what is the paradox?

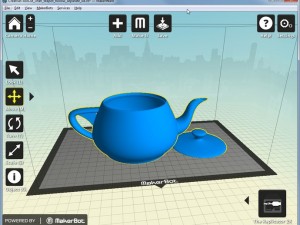

The huge reduction in marginal cost shook those industries and is now beginning to reshape energy, manufacturing and education. Although the fixed costs of solar and wind technology are somewhat pricey, the cost of capturing each unit of energy beyond that is low. This phenomenon has even penetrated the manufacturing sector. Thousands of hobbyists are already making their own products using 3-D printers, open-source software and recycled plastic as feedstock, at near zero marginal cost. Meanwhile, more than six million students are enrolled in free massive open online courses, the content of which is distributed at near zero marginal cost.

Did you know the author has a new book about ‘The Zero Marginal Cost Society’? Again, there have always been industries with high fixed costs and low marginal costs. He mentions solar and wind technology, but hydro power, an old technology, has always maintained very low marginal costs. MOOC’s may have close to zero marginal cost, but (1) they deliver something different from the experience of an in-person class, and (2) the costs of responding to student questions and assessing their work does not change when the content is delivered online rather than in a classroom. And as for 3-D printers? I think the jury is out as to whether they will replace manufacturing, especially if reliant on ‘zero marginal cost’ recycled plastics.

Industry watchers acknowledge the creeping reality of a zero-marginal-cost economy, but argue that free products and services will entice a sufficient number of consumers to purchase higher-end goods and specialized services, ensuring large enough profit margins to allow the capitalist market to continue to grow. But the number of people willing to pay for additional premium goods and services is limited.

I’m not sure who these ‘watchers’ are. But pricing for premium services is an old technology, and commonplace. And while of course the number of people willing to pay for premium is, in a sense, limited, it might well be enough. Amazon Prime is fairly popular, yes?

Now the phenomenon is about to affect the whole economy. A formidable new technology infrastructure — the Internet of Things — is emerging with the potential to push much of economic life to near zero marginal cost over the course of the next two decades. This new technology platform is beginning to connect everything and everyone. Today more than 11 billion sensors are attached to natural resources, production lines, the electricity grid, logistics networks and recycling flows, and implanted in homes, offices, stores and vehicles, feeding big data into the Internet of Things. By 2020, it is projected that at least 50 billion sensors will connect to it.

People can connect to the network and use big data, analytics and algorithms to accelerate efficiency and lower the marginal cost of producing and sharing a wide range of products and services to near zero, just as they now do with information goods. For example, 37 million buildings in the United States have been equipped with meters and sensors connected to the Internet of Things, providing real-time information on the usage and changing price of electricity on the transmission grid. This will eventually allow households and businesses that are generating and storing green electricity on-site from their solar and wind installations to program software to take them off the electricity grid when the price spikes so they can power their facilities with their own green electricity and share surplus with neighbors at near zero marginal cost.

For all this talk of the ‘Internet of Things’ (Evgeny Morozov would have a field day with this), ‘big data, analytics and algorithms’, the one example given is the use of dynamic pricing of electricity, which is a useful innovation to be sure, but far from clear that there are implications for all of life, the universe, and everything. And it really doesn’t have much to do with ‘zero marginal costs’ – the electricity generated might have higher or lower marginal costs, and still be amenable to dynamic pricing.

And now the piece shifts gears:

The unresolved question is, how will this economy of the future function when millions of people can make and share goods and services nearly free? The answer lies in the civil society, which consists of nonprofit organizations that attend to the things in life we make and share as a community. In dollar terms, the world of nonprofits is a powerful force. Nonprofit revenues grew at a robust rate of 41 percent — after adjusting for inflation — from 2000 to 2010, more than doubling the growth of gross domestic product, which increased by 16.4 percent during the same period. In 2012, the nonprofit sector in the United States accounted for 5.5 percent of G.D.P.

A big jump has been made, that because we can now magically share goods and services ‘nearly free’ (and he has not come close to establishing this), nonprofits will take center stage. This ‘powerful force’ (at 5.5 percent of GDP?) has been growing, that is true, but it is worth thinking about why. That health care costs have continued to rise at a rate much faster than the economy as a whole is not an indication that we are in any way a more civil society. The (not very new) analysis of cost disease always predicted we would begin to spend less on manufactured goods and more on services, particularly those that are delivered in ways that don’t allow for much substitution of capital for labor. I do not see how nonprofit growth as a proportion of the economy is linked to Napster or solar power.

Nowhere is the zero marginal cost phenomenon having more impact than the labor market, where workerless factories and offices, virtual retailing and automated logistics and transport networks are becoming more prevalent. Not surprisingly, the new employment opportunities lie in the collaborative commons in fields that tend to be nonprofit and strengthen social infrastructure — education, health care, aiding the poor, environmental restoration, child care and care for the elderly, the promotion of the arts and recreation. In the United States, the number of nonprofit organizations grew by approximately 25 percent between 2001 and 2011, from 1.3 million to 1.6 million, compared with profit-making enterprises, which grew by a mere one-half of 1 percent. In the United States, Canada and Britain, employment in the nonprofit sector currently exceeds 10 percent of the work force.

Despite this impressive growth, many economists argue that the nonprofit sector is not a self-sufficient economic force but rather a parasite, dependent on government entitlements and private philanthropy. Quite the contrary. A recent study revealed that approximately 50 percent of the aggregate revenue of the nonprofit sectors of 34 countries comes from fees, while government support accounts for 36 percent of the revenues and private philanthropy for 14 percent.

I took my first economics class in 1977, and have been around economists ever since. I have not met a single one of the ‘many economists’ who argue the nonprofit sector is a parasite.

I wouldn’t take so much attention on this, except that this is so remarkably incoherent, and appeared in the Week in Review. For analysis of trends in nonprofits and civil society, the Times could do a lot better.

Leave a Reply