At Marginal Revolution (which often has posts on the economics of the arts – you should be reading it!), Tyler Cowen points us to Paleofuture, which gives a 1940s version of the ‘kitchen of the future.’ We would no longer use dishes (‘antiques’) since our food would be processed and dehydrated.

At Marginal Revolution (which often has posts on the economics of the arts – you should be reading it!), Tyler Cowen points us to Paleofuture, which gives a 1940s version of the ‘kitchen of the future.’ We would no longer use dishes (‘antiques’) since our food would be processed and dehydrated.

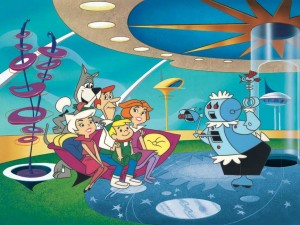

The 1960s cartoon The Jetsons imagined some similar changes in interior design, although the cooking and cleaning would be done by a robot maid.

What has interested me about visions of the future is that they share a common bias: the aspect of the world undergoing the most significant change at that time is expected to continue along an innovative path, and aspects that are relatively static at that time are expected to remain so. In mid-century we saw advances in processed foods. And so it was imagined that these would eventually completely replace non-processed foods. No more farmers’ markets. And assembly line technology increasingly relied on advances in robotics. If robots could punch rivets in cars on an assembly line, why wouldn’t it eventually be the case that they clean our homes?

What has interested me about visions of the future is that they share a common bias: the aspect of the world undergoing the most significant change at that time is expected to continue along an innovative path, and aspects that are relatively static at that time are expected to remain so. In mid-century we saw advances in processed foods. And so it was imagined that these would eventually completely replace non-processed foods. No more farmers’ markets. And assembly line technology increasingly relied on advances in robotics. If robots could punch rivets in cars on an assembly line, why wouldn’t it eventually be the case that they clean our homes?

Consider that the Jetson family would view television on their wristwatch. In the 1960s watches were getting more sophisticated, and so the expectation was that in the future we would have the most amazing wristwatches. But we don’t. We have amazing telephones, which are very small and we can carry anywhere, and use them to watch tv and catch up on the news and send messages to friends and play games and take pictures. Oh, and talk on the telephone too. And they’ll tell us what time it is. But no one saw that coming – telephony was, in most people’s eyes, a fairly static piece of technology.

Consider that the Jetson family would view television on their wristwatch. In the 1960s watches were getting more sophisticated, and so the expectation was that in the future we would have the most amazing wristwatches. But we don’t. We have amazing telephones, which are very small and we can carry anywhere, and use them to watch tv and catch up on the news and send messages to friends and play games and take pictures. Oh, and talk on the telephone too. And they’ll tell us what time it is. But no one saw that coming – telephony was, in most people’s eyes, a fairly static piece of technology.

Or, to leave the world of cartoons, consider the book and the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. We see technological innovation on two fronts: space travel, and computers. The advances in space travel are vastly over-estimated. But in the 1950s and 1960s space exploration was moving at a rapid pace, and that pace was projected to continue such that we could explore other galaxies. Computers were advancing to some degree, but as you watch the film notice how it seems to under-estimate the advances in information technology and telecommunication. Who could have known?

It is inherent in the nature of technological change that we do not know what is coming next. If we know future technology, then it’s not really future, it’s current. And guesses about what the future brings are prone to bias – we project the most active current spheres of technological change into the future, when there is no guarantee that such trends will continue.

It is inherent in the nature of technological change that we do not know what is coming next. If we know future technology, then it’s not really future, it’s current. And guesses about what the future brings are prone to bias – we project the most active current spheres of technological change into the future, when there is no guarantee that such trends will continue.

Footnote: I went camping on the weekend, and brought along, of course, a Coleman two-burner stove. These were developed in the 1930s, and are essentially unchanged since then – an amazing piece of technology. Not sure what people in the 1940s thought camping would be like in 2013; they might be surprised to know we still make breakfast the same old way.

I’ve often noticed the “paleofuture”‘s (great term) overemphasis on transportation technology relative to information technology myself. In addition to the fallacy that you pointed out (assuming that the greatest advances will be in familiar territory), I think we also are bad at seeing technological walls coming. That is to say, human space travel stopped advancing because we were not able to achieve economies of scale such that it made sense for us to keep pushing on it to the same extent. Computer processing power, by contrast, has advanced according to Moore’s Law for decades now. But now that looks like it’s hitting a wall: http://www.wired.com/insights/2013/08/is-silicon-dead-or-can-we-expect-more-from-moores-law/

The scary thought is that these bursts of technological progress are the exception rather than the rule, a la Tyler’s Great Stagnation hypothesis. I haven’t read the book, but I wonder how our society would/will adapt to a dramatic slowdown in innovation.

In 1909 E. M. Forster wrote a novella called The Machine Stops that did an astonishing job of predicting the future. In it he imagined a grand, unifying, intelligent machine that satisfied all human needs, facilitated all human interaction and gradually insulated civilization from direct experience with the world. I think he got so much right because he wrote about complacent Edwardian’s who were all too willing to let machines take over. He didn’t ask what machines could do, he asked what people were likely to let machines do, and I think that made all the difference.

And the book has camping, too!

Thanks for the pointer on the Forster story, I did not know of it, but will look for a copy.

As for Ian’s question: it is a scary thought, since innovation means economic growth and growth means greater ability to enact policies that benefit the general population. Stagnation makes any policy change take on the quality of zero-sum, and groups fight to protect what is theirs. But I’m not sure Tyler is right …

I just read a bit about the economic theories of that Prof. Gordon at Northwestern University, whom I believe has influenced Tyler Cowen’s thinking a bit, and I recognize a bit of truth in what they suggest. All my parents had to do to give me a chance to progress a little further than them economically was to send me to college, and then I went a step further and got a graduate degree. In one of the great ironies of our age, my dad worked for 30 years in a factory a half-block from our home where he actually made things. I drive 35 minutes from an inner-ring suburb to a converted factory in the downtown of a small city — we use the factory to produce operas. I am sending my kids to college, but they would actually have to go to get a doctorate to have more formal education than their parents, and in this day and age, that doctorate would not be a guarantee of any additional financial security.

Well, I’m not sure what the point of all this was…but I’ve got to get back to work…enjoy reading your blog, Michael…and please feel free to choose not to post this…