I posted re scalpers a few weeks ago. The forthcoming New York Times magazine has a story on ticket resale. It is, well, unsatisfying. The problem at hand is this: if so much money is to be made through ticket resale, why have the artists or concert promoters not done what they can to capture that money? Why leave it on the table for scalpers and StubHub?

I posted re scalpers a few weeks ago. The forthcoming New York Times magazine has a story on ticket resale. It is, well, unsatisfying. The problem at hand is this: if so much money is to be made through ticket resale, why have the artists or concert promoters not done what they can to capture that money? Why leave it on the table for scalpers and StubHub?

Put in other terms, why aren’t initial ticket prices closer to the level where the resulting demand would more closely approximate the capacity of the venue?

From the Times:

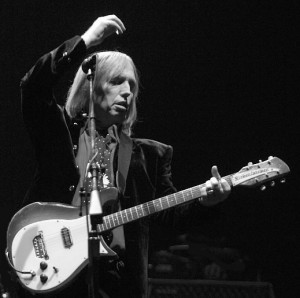

[Bruce] Springsteen’s style [of offering low ticket prices that sell out very quickly] might seem more altruistic, but performers who undercharge their fans can paradoxically reap higher profits than those who maximize each ticket price. It’s a strategy similar to the one employed by ventures like casinos and cruise ships, which take a hit on admission prices but make their money once the customers are inside. Concert promoters can overcharge on everything from beer sales to T-shirts, and the benefits of low-priced tickets can accrue significantly over the years as loyal fans return. In part, this explains why artists like Springsteen and [Tom] Petty are content to undercharge at the gate while others, perhaps wary of their own staying power, are eager to capitalize while they can.

But so far as I know, casinos and cruise ships do not charge admission prices such that capacity is quickly reached, with disappointed potential customers turned away who would have been willing to pay a high price for entry.

Further, if 15,000 people are going to attend a concert whether by paying just $50 per ticket (leaving significant excess demand for tickets) or by paying $125 per ticket (which still fills the hall), how does that affect the demand for beer and shirts? Not by $75 per person, I would think.

Finally, it seems that low ticket prices might make it less likely loyal fans return. If prices are so low that demand for tickets exceeds supply by, say, 4 to 1, then getting a ticket is something like a lottery, and the person who wins that lottery once is likely to lose next time. Fans will have a tough time returning – how do they ensure they can always get a seat? Higher prices ensure that tickets are sold to those most willing to pay, and they are the ones likely to return over the years.

And so we still have a mystery…

Ticket sales for pop concerts are systemically different from those for classical music performances. People by tickets for *particular* pop stars who generally only visit cities once a decade or so. Classical performances require subscribers who attend 5 to 10 times a year. Very few people attend 5 to 10 pop concerts per year even if they are fans of a wide range of stars.

Little cities in Europe like Pforzheim Germany or Innsbruck Austrian only have populations of 120,000 but own and operate fulltime, year-round opera houses. They fill the seats because the tickets are affordable – generally about 80 dollars for the best seat in the house, or 30 dollars for a good average seat. American opera tickets are on average about 4 to 5 times more expensive. This is one reason small cities under our private funding system can’t have opera houses, much less ones the run all year round.

In short, affordable tickets make a big difference in classical music. Sometimes operas are so popular in cities like Munich or Vienna that they have to distribute the tickets using a lottery system. America, by contrast, offers very short seasons, and in only a few cities, and solves ticket shortages by offering priority ticket sales to wealthy donors…

I would posit three factors driving scalping that you have not addressed: syphoning off supply to better match demand over time, better segmentation and pure profit maximisation at the expense of fan loyalty.

Can you list concrete examples of these three factors affecting classical music?

William

I was addressing the original article and post, but I will give some thought to some examples as relevant to classical music as you request.

Regards

Tim Roberts

In general, classical music presenters have so much inventory that supply rarely outstrips demand to the extent that scalping becomes a reasonable alternative. Good symphonies and other classical presenters are getting better at pricing their tickets, but often to maximize attendance rather than revenue. In the touring pop world, Bruce Springsteen can’t be seen to be maximizing revenue, given his blue-collar roots; his people feel strongly that equalizing access (or at least pretending to) for all to his concerts is paramount. They make their money in lots of other ways.

As a marketing director and now consultant to arts organizations, I can tell you what happens when an event is expected to stimulate high demand. 1) Its ticket price is originally set in relation to other, less popular events, as all events are seen by the presenter to be equally precious, 2) as demand outstrips supply, a dynamic pricing scheme is kicked in, 3) the board and leadership are afraid of being seen to take advantage of the poor patrons, so still keep the price artificially low, and 4) the event sells out far in advance, making the board and leadership feel good.

I oversaw exactly this train of events a couple years ago as the performing arts center I worked for had a hugely popular event. The top price was originally $65 (too low by half), as demand went wild it was raised to $90 and then $125, and the board panicked and would not allow higher prices. So I stood in the box office the evening of one of the performances and was called to a window to deal with a couple who had purchased fake tickets online for $285. Each. Which we then had to make good out of our house seats. At another $125 each. For a grand total of $820 the pair (which, had they been bought earlier would have cost $130).

Non-profits are fortunate when demand exceeds supply (though this is often for only a small number of the season’s programs.) Does that mean they should raise prices for popular events, or should they think in terms of serving the common good by insuring that a wide demographic has relatively equal access to high culture? Is that simply the Board and leadership trying to feel good, or is there a more fundamental democratic process at work?

Pop concerts are for profit so what applies to them might not in some cases be very relevant to non-profit performance organizations. Hence my thought that it is important to not to blur these distinctions. Anyway, data about possible scalping of non-profit tickets would be interesting.

No one commented on what seems to me a key point in the Times article: “Many scalpers now use computer programs to monopolize ticket buying when seats go on sale, which forces many fans to buy from resellers. ”

If only in the interest of fairness, shouldn’t the promoters do something to prevent that happening?

I thought ticket companies do try to combat bots? But I guess they have limited incentive to fight too hard, they still get their pound of flesh for the sale of the seat and it perpetuates the notion that they sell out to huge numbers of fans. They only seem to get annoyed when someone else uses these tickets to make additional “unauthorised” profit.

“Fairness” is the issue. But fair from who’s perspective? Commercial entertainment promoters have a very different view necesssitated by their business model and stakeholders compared to many sports teams, let alone not for profit theatre companies or orchestras.

The main use of the concept of fairness by promoters seems to be when they too are denied any additional income on a ticket, similarly many artists. But we also hear as many stories of promoters and artists holding inventory back and scalping their own tickets. It seems most times the average consumer is the one that loses out.