In the New Yorker this week, Malcolm Gladwell reviews (with high praise) a new biography by Jeremy Adelman, Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman. I have not read the biography, but I do highly recommend Gladwell’s essay.

In the New Yorker this week, Malcolm Gladwell reviews (with high praise) a new biography by Jeremy Adelman, Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman. I have not read the biography, but I do highly recommend Gladwell’s essay.

One of Hirschman’s most famous works is Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. What do we do when we become unhappy in one of our business relationships: a coffee shop whose service is not as friendly as it used to be, a workplace that has become problematic? Traditional economic theory as taught in textbooks answers: we leave. We stop going to the old coffee shop and find a new one. We start looking for another job with a better package of pay and working conditions. If we don’t like what our local theatre company is producing, we stop going to the theatre.

What traditional economics did not usually suggest was that there is an alternative to this strategy of “exit.” Hirschman asked: what if we use our voice and, instead of leaving, let the management know we are dissatisfied and why? We can let the owner of the cafe, or our employer, know there is a problem. Hirschman suggested sometimes this is the superior strategy. Ask yourself: will we end up with better educational and life outcomes if private schools arise so that parents can take their children out of unsatisfactory public schools, or if parents get involved in trying to make their local public schools better? Sometimes exit is the better option, but not in all cases.

An interesting case regarding pricing this week, from England. The Guardian reports:

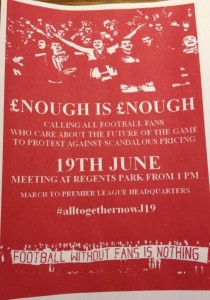

The Globe pub, opposite Baker Street Tube station in London, is normally the gathering point for raucous shows of partisanship ahead of Wembley finals. But on Wednesday there was unity in the air, as well as righteous fury, as rival fans gathered over a pint before a march onPremier League headquarters to protest against ticket prices. Rather than baiting one another, cries of “You greedy bastards, enough is enough”, “We hate Sky Sports and we hate Sky Sports” and “Supporters, united, will never be defeated” filled the air as Arsenal fans marched alongside their Spurs counterparts and Liverpool supporters joined forces with Manchester United diehards.

“We’ve had enough. We’ve just got to let the Premier League know how we feel,” said John Bonfield, a Spurs fan from Hackney, who said he felt his club would simply charge whatever it could get away with. The genesis for the march was a pair of meetings organised by more than 15 supporters’ groups in the north west and in London, with Liverpool’s Spirit of Shankly as the driving force, in the wake of protests against away ticket prices at the Emirates and elsewhere last season.

Organisers said the level of co-operation on show represented a turning point, with anger exacerbated by the new £5.5bn TV deal. “With the TV deal, no football club should have increased ticket prices. They’ve been able to get away with it because there was no challenge. The challenge starts now,” said Stephen Martin of Spirit of Shankly. “We’re all here for the common cause. When we play them, the rivalry will always be there. But we can all see the bigger picture. There must be 40 different club tops here today.”

Two things of interest in the story. The first is the use of the strategy of voice, loud and clear. It might not work, but in a sector that relies on fan loyalty one has to believe the owners are paying attention.

The second is one of the arguments used by fans, appealing to the self-interest of the owners:

An oft-heard argument was that the value they created in terms of atmosphere, packaged into a TV product worth £5.5bn over three seasons, was under-appreciated. Around half those marching were children of the Premier League era in their twenties, concerned they would be driven to watch matches on television rather than with their friends inside grounds.

“If we keep sticking with the way it is now, then eventually dads won’t be able to take their kids to the game anymore and eventually the atmosphere in the grounds will die. The lad on the other end of the flag has been on the coach with us for every game home and away but he can’t afford to get into the ground,” said Adam Kearns, 26, a gas fitter from Liverpool clutching a banner proclaiming “If you tolerate this then your children will be next”.

In other words, the value of the televised product, and the brand marketing, will fall if the live attendance falls, and with it the atmosphere that makes the games, even on television, more interesting.

Leave a Reply