Yesterday I posted on recent economic research regarding women’s and men’s wages, and the impacts, perceived or real, on marriage and family. I would be writing up another post on pricing, the ostensible topic of this blog, were it not for a new post by economist Emily Oster at Slate on the household division of labor.

Yesterday I posted on recent economic research regarding women’s and men’s wages, and the impacts, perceived or real, on marriage and family. I would be writing up another post on pricing, the ostensible topic of this blog, were it not for a new post by economist Emily Oster at Slate on the household division of labor.

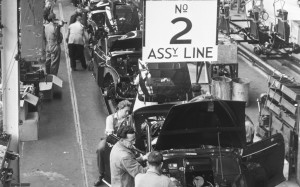

She asks whether it is efficient for partners in a household with children to specialize, one in the market workforce and the other managing the household (trivia: the etymology of “economics” is from the Greek for household management). Her goal is to put aside all other considerations of equity and power and just enquire into efficiency – getting the most out of the limited human and financial resources you have to work with. She notes Gary Becker’s work on the economics of the family, in which he treats the household as a kind of firm. And in a simple model of the firm, it is most efficient for “employees” to specialize. This is an old idea, noted near the very beginning of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776), in which he observes an assembly line at a pin factory, seeing the great increase in production that arises from each worker specializing in a specific task. Emily Oster concludes that, yes, specialization is a good idea, but so is outsourcing (which is a form of using the market to achieve specialization in tasks), hiring a gardener, a plumber, a painter, a nanny, rather than trying to get all tasks done internally with just two workers.

There is no disputing the logic of the model. But …

Adam Smith wrote about a firm producing pins. The team of workers got very efficient at producing that single item. But I will bet that no worker on that assembly line ever came up with many good ideas on how to change the design of the line, or of the finished product. Teams that specialize get very good at getting routine tasks done, but they are not necessarily the best for generating innovation, which requires conversation and the play of ideas amongst different people. A couple where both are in the workforce and both contribute to the household, and the raising of children, allows for two people with different networks of friends and colleagues to exchange ideas and come up with better solutions to problems than two people who completely specialize in tasks. At day’s end, when the children are asleep, spouses who share in tasks and who are not completely specialized can better talk about events, dilemmas, plans, solutions. One spouse could take on the task of all the gardening, or all the cooking, but it will be a more interesting garden and dinner table when these tasks are shared, even when one is somewhat more talented at the task than the other. Raising children is not like making pins.

Arts organizations, creative organizations, do well to think about this. Yes, on the orchestra stage we want the cellist to specialize in playing the cello and the trumpeter to specialize in playing the trumpet. But behind the scenes, isn’t it true that the more all employees understand about marketing, fund development, outreach, finance, the more creative the management team will be? And isn’t it also true that the more arts managers learn about the challenges facing non-arts organizations, and how firms go about solving them, the more creative they will be in their own organizations?

Leave a Reply