Paul Krugman writes about the decision by Google to shut down Google Reader. Whatever your thoughts on the good or evil nature of Google, he raises an important issue for thinking about price discrimination: there are cases where, if no price discrimination is possible, such that the seller can only charge one price to all, there does not exist a price that can possibly allow the firm to cover its costs. And this is true even if the total value consumers place on the good (as measured by their reservation prices – their willingness to pay for it) is greater than the total cost of provision.

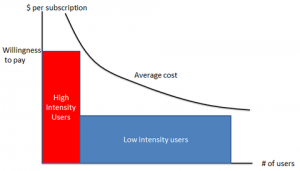

He illustrates with the diagram to the left. Average cost – the cost per subscriber – falls with the number of users, as there are high fixed costs to provide the service but low marginal costs per additional user. If a high price is charged to reflect the reservation prices of the high demand customers, the total revenue is the red rectangle, but that doesn’t cover costs (where average cost is given by the curve, and lies above the rectangle). If a low price is charged to reflect the reservation prices of low intensity users, total revenue is the blue rectangle, but that doesn’t cover costs either. And yet, if it were possible to charge customers according to their individual reservation prices, costs could be covered – revenues would be the sum of the two rectangles – and we would have the service.

Nonprofits in the arts are often in this situation. They too have declining average costs, and they need to price discriminate, or indeed get donors to voluntarily price discriminate, in order to cover costs. No single price will work. And here Krugman is suggesting it is true for certain for-profit goods as well. As he notes, in some cases we leave it to the public sector to provide the valued service when the for-profit sector cannot, but that is not very applicable to IT services since the state will lack the ability to innovate in the way for-profit firms can.

In class when I begin to discuss price discrimination, students can initially react as if there is something rather unsavory about the practice, that it is underhanded, a “trick” played on customers. But it isn’t – it is often the only way a good can be provided. The ability to offer both hardcover and paperback books is necessary to keep publishers afloat (something that is not always easy) – they could not make the same revenue if they could only offer one version of each book. As a reader I am glad they do this. Sometimes I’ll buy hardcover, sometimes I’ll buy paperback. I understand the reason why the price differential exceeds the difference in cost of production and shipping, and I understand why they delay the release of the paperback. I might wish for it to come out sooner, but I don’t wish for a world where publishers go bankrupt for inability to cover costs. Price discrimination is good for me as a consumer – it brings goods to market that otherwise would not be available at all.

[…] seen in the Veronica Mars Kickstarter, price discrimination, price discrimination, and more price discrimination. WHY DOES NO ONE TELL ME THESE THINGS. (Side note: Michael asks why people [incorrectly] think […]