American Ballet Theatre / City Center, NYC / October 16-20, 2012

American Ballet Theatre, financially afflicted like many a dance company in these stringent days, gave a Fall “season” consisting of just one “week”—October 16-20. Did the brevity of the run ensure the excellence of the repertory? Presented at the City Center, it consisted of seven ballets or stand-alone excerpts, none of which was filler or “novelty.” Most were safe (and worthy) favorites—Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo, for instance; Antony Tudor’s The Leaves Are Fading; Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room. The most thrilling item by far was the first of three new ballets that Alexei Ratmansky plans to set to Shostakovich scores. To this choreographer—Russian-born and trained, once head of the Bolshoi Ballet—Shostakovich is the composer who holds the place that Tchaikovsky did with Petipa, Stravinsky with Balanchine. The new piece is called, austerely, Symphony #9.

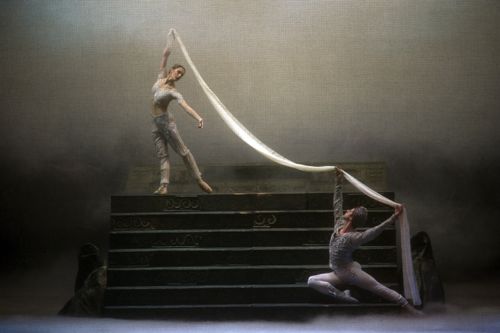

ABT’s Polina Semionova and Marcelo Gomes in Alexei Ratmansky’s Symphony #9, named for its Shostakovich score

ABT’s Polina Semionova and Marcelo Gomes in Alexei Ratmansky’s Symphony #9, named for its Shostakovich score

Photo: Gene Schiavone

But what else might it have been called? It portrays both the literal and the abstract without a second’s pause between modes. Is that a platoon or a corps de ballet going through its maneuvers? It’s both. Simultaneously. And yet the mingle coheres. As Balanchine’s did (and continues to do), Ratmansky’s work trains his viewers’ eyes to see more swiftly and keenly.

The dance, in intimate communication with the music, evokes the inevitable death toll of war juxtaposed with the ecstasy of victory. Ratmansky, well endowed with the ability to perceive myriad attitudes to a situation in close range, revels in such ironic possibilities even to the extent of showing a latent vein of humor in them. Is s/he really dead? you wonder when a body collapses, or is s/he just playing dead? Why are the bodies often stricken in stop-motion mode? And what role do these strange views of the action play in the ballet’s overall treatment of events and emotions? As usual, the moment you’ve seen a Ratmansky ballet for the first time, you want to see it a second time to have questions like these answered as well as having the opportunity to revel in the choreography’s command of structure and its sheer theatrical power.

Semionova and Gomes in Symphony #9

Semionova and Gomes in Symphony #9

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Unlike some of Ratmansky’s earlier works, even the most rewarding (Namouna, for instance), Symphony #9 was tight as a drum at its premiere on October 18. The dancers’ vitality and precision were at a peak I haven’t seen at ABT in ages.

It’s no surprise that the challenging choreography does much for its leading dancers. Marcelo Gomes looks more than ever like the Big Man on Campus, only one whose personality includes a devilish sense of humor. Polina Semionova discards her usual type-casting as the girl who can do every damn step perfectly and becomes a real (and way sexy) woman. Simone Messmer, hair cropped short like that of the feisty heroines of yesteryear’s books for girls (think Jo March, after she sheds her tresses), proves herself, once again, to be an original. Craig Salstein is the boy who dares—part Rookie of the Year, part class clown—with a serious under layer that should free him forever from roles that conceive of him as “the hero’s best friend.” Ratmansky takes all these talents in hand and makes them more wonderful than they or we could ever have imagined on our own.

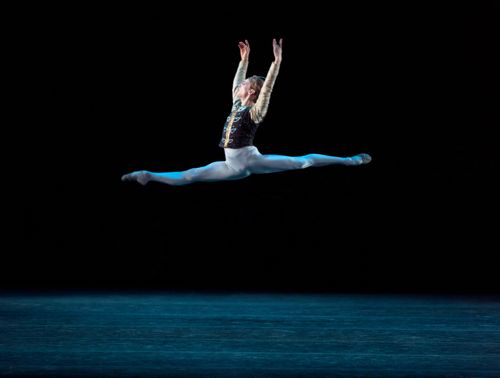

Herman Cornejo in Symphony #9

Herman Cornejo in Symphony #9

Photo: Gene Schiavone

And I haven’t yet mentioned Herman Cornejo, who, so very rightly, is assigned no partner. He emerges, gradually, as the pivot of Symphony #9 or, if you will, its soul. The audience’s reaction to the solo with which he closed the ballet made me think of an ardor that, almost literally, wanted to devour him. The ballet’s curtain line is his stream of tours à la seconde (the body whirling as if without end, one taut leg extended parallel with the floor) mapping out an earthly geometry. To think that many a viewer once believed he wasn’t tall enough or conventionally handsome enough or whatever enough to be a danseur noble—in other words, fit to play a prince! Cornejo is the model of a post-modern danseur noble—technically breathtaking yet never show-offy, and infinitely thoughtful. I’ve never heard him speak a word. I’ve never needed to.

Needless to say I went back to see the second cast—which proved to be nowhere near as effective as the first, though things may improve to a certain extent with further rehearsal and further performance. In the Gomes role, Roberto Bolle, who can’t act, tried to, ineffectually, while in the Semionova role, Veronika Part, who can, did so, puzzlingly, with soap-operatic exaggeration. Jared Matthews, assigned the Cornejo part, was as valiant as a good dancer can be when faced with a challenge to which he’s neither equal nor suited.

Symphony #9 ensemble

Symphony #9 ensemble

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Symphony #9’s glamorous black and white costumes, by Keso Dekker, feature the slashing contrast of shades. The menswear is hugged by a belt of giant rhinestones; the hems of the women’s striated skirts brush the ladies’ knees as if murmuring to the wearers about what’s going on. The graduated darks and lights of Jennifer Tipton’s illumination provide many an apt mood clue, though the feelings charted by the choreography would be evident even on Times Square in relentlessly dazzling sunlight or in dusk shading ominously toward a complete black-out.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias