New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 15 – February 24, 2013

The New York City Ballet’s two-week festival (January 15-27, 2013) of Balanchine’s choreography to music by Tschaikovsky came with a guarantee: no duds, no Eurotrash or other Terpsichorean fads, no feeble imitations of the greats. How wonderful it was to head for Lincoln Center night after night, knowing one was about to encounter dance that was sublime, to music by an ideal partner.

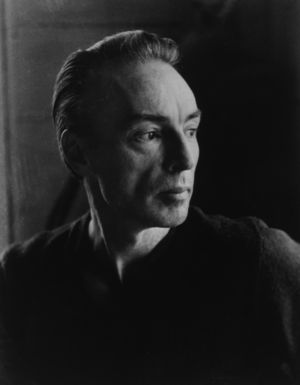

George Balanchine (1904 – 1983)

George Balanchine (1904 – 1983)

Photo: Tanaquil LeClercq

The ballets presented were: Allegro Brillante, Diamonds (from Jewels), Divertimento from “Le Baiser de la Fée,” Mozartiana, Serenade, Balanchine’s one-act version of Swan Lake, Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux, Tschaikovsky Suite No. 3, Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 (once known as Ballet Imperial), and Tschaikovsky Suite No. 3.

Serenade, the first ballet Balanchine made in America, and the one he told Karin von Aroldingen (a dancer in the company who had become a close friend), was the one that might outlast him, proved its claim on immortality once again. Its invention, its pervasive beauty, its hidden story (slightly different, it seems, for every viewer, but universally poignant) worked their familiar magic. The cast I saw was headed by Ashley Bouder, Megan LeCrone, Sara Mearns (making her debut as the principal woman), Jared Angle, and Adrian Danchig-Waring. They and the rest of the participating dancers seemed to have absorbed the choreography through their skin.

I loved Balanchine’s Divertimento from “Le Baiser de la Fée” from the moment I first saw it. He gives it only a touch of plot (from the Hans Christian Andersen tale The Ice Maiden), but it’s enough to knock you flat. The choreographer, who had a mystic streak of his own, portrays the fate that haunts an artist whose talent proceeds from a fairy’s kiss—a blessing, yes, but one that dooms him to destruction. Tschaikovsky, who had a fatal instinct for tragedy, was very much at home with this theme.

The ballet is dense with haunting moves and portrays the implacable separation of a loving couple who seemed, at first, destined for a happy ending. (Does the woman represent one of the “ordinary” joys of life that an artist may have to forego or, perhaps, life itself?)

If you’re old enough and lucky enough, you’ll have seen the originators of the leading roles: Helgi Tomasson—for whom Balanchine here created one of his greatest male solos, full of sweeping, windblown movement—and Patricia McBride, whom I think of as an artistic ancestor of the wonderful Tiler Peck.

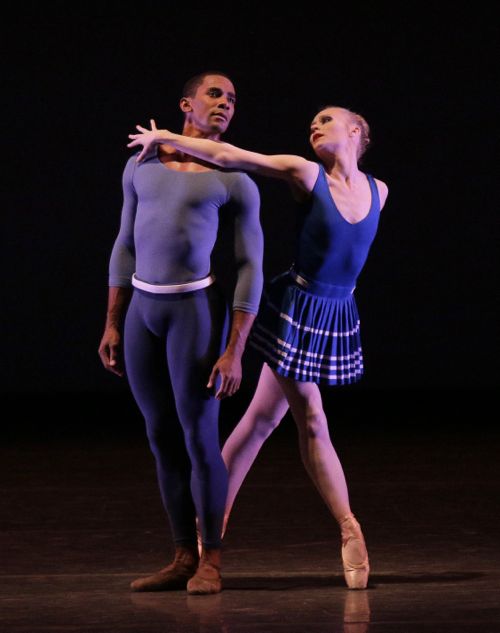

Allegro Brillante looked as if it had been made with Peck in mind. She is more than swift, strong, and accurate; she’s musical as well. So her speed and dazzle were tempered—or, let’s say, complemented—by a seemingly intuitive sense of phrasing. Her performance in this ballet is enhanced by her ability to take physical challenges as occasions for pleasurable play. She was partnered by Amar Ramasar, a very attractive fellow, whom the viewer is meant to find persuasive, but hardly a virtuoso.

The Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux was assigned to Megan Fairchild, who can be counted on to nail every step in the classical vocabulary but who but doesn’t manage to tell her audience anything in the process. If Balanchine had been around to give the crew his much repeated admonition “Don’t think, dear; just dance,” Fairchild could be said to take that advice too seriously. She was partnered by Joaquin De Luz, a small high-flyer.

Diamonds, the least compelling segment of the tripartite Jewels, gave us Sara Mearns, back from a long hiatus due to injury, dancing an eloquent duet with Ask la Cour—trained by the Danes (as Peter Martins was), who has suddenly come into his own as an artist.

Balanchine’s one-act Swan Lake shows the master at work at a useful project. “If you want to sell tickets,” he reportedly declared, “make a ballet and call it Swan Lake.” He had keen theatrical know-how and understood that, to fill the house, the company could not live on his “leotard ballets” alone, though they remade classical dancing forever. His abbreviated version of Swan Lake—especially in the work for the corps, placated the popular audience, assuring it that beauty in its simpler forms has its own virtues.

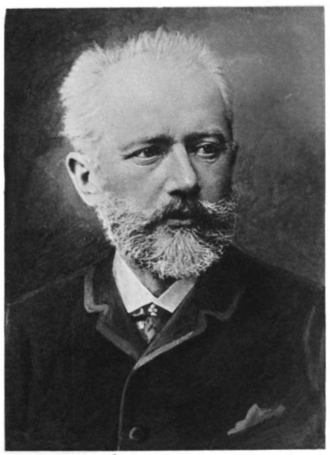

Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893)

Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893)

Imposing and evocative at the same time, Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 might be said to have marked the coronation of Teresa Reichlen as a ballerina, no longer merely the strawberry blonde with the endless legs and the firm technique. I wrote about this ballet in my previous piece, Tschaikovsky, A Balanchine Muse, and, having seen it again, am still marveling. Once titled Ballet Imperial, with décor and costumes to match, it has divested its storybook trappings to become regal in the abstract.

Tschaikovsky Suite No. 3 goes on for three movements with rather too much pink in the women’s flowing costumes, the women’s unbound hair treated as a fetish, and a pervasive mood of romance. In the fourth and final movement, to a musical theme and variations, it becomes a far sterner and challenging ballet, with Ashley Bouder and Jonathan Stafford leading the proceedings. I found myself semi-susceptible to the piece when I was younger; now those first three movements seem almost jejune.

The sole dissonant note in the two weeks was the rerun of a pièce d’occasion by Peter Martins the occasion of which had passed: Bal de Couture proved to be little more than a catwalk affair to display fancy-dancey costumes by the fashion designer Valentino, whom the company had already made too much of last season. These costumes fail to conform to the needs of the dancing body, making it look slightly misshapen; their palette is simplistic—red, black, and white; and they boast qualities that may be appropriate to high-end social life, but only impede the needs of complex, high-velocity movement. The Tschaikovsky music from the opera Eugene Onegin was not sympathetically served.

I know that Chanel once provided costumes for Apollo and I’ve actually witnessed Christian Lacroix’s raucous wardrobe for ABT’s Gaîté Parisienne. In general, though, I feel that the best resource for dance costumes is—to shift metaphors—cobblers who stick to their last. I can’t fathom any artistic reason for following, in dance, the interests of the rich (and those craving the indulgences of same) in catwalk clothes. For one thing, it’s likely to make the audience suspicious of even worthy attempts to couple dance with glad rags.

NOTE: In my previous SEEING THINGS piece—Tschaikovsky, a Balanchine Muse—I wrote about Balanchine’s Serenade, Mozartiana, and Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2.

© 2013 Tobi Tobias