New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / September 17 – October 13, 2013

The New York City Ballet opened its fall season at the David H. Koch Theater with a week of Swan Lakes—broken only by a trio of new works for the gala on September 19. The version was Peter Martins’s, which, typically, illustrates the choreographer’s adamant conviction that “less is more.” Needless to say, the stubbornly “clean” edition is likely to make a newbie viewer wonder what, indeed, this legendary piece is about. In its more generous renderings, Swan Lake has a great deal to say about the human experience: the power of love; the unmitigated threat of evil; and the tenacity of the heart. Tschaikovsky’s score is saying it all along.

To give credit its due, the dancing was well-nigh impeccable, every step sharply executed, from principals through corps members. A video work tape of the piece would provide an admirable device from which to learn the bare-bones aspect of the choreography. The phrasing was often musical, too. Still, the absence of “soul”—the quality that makes the steps sing, or tear at the viewer’s heart—is woefully neglected. Balanchine often forbade his dancers to indulge in “acting”—that is, acting that is superficial, and thus fake. Peter Martins squelches even genuine feeling itself. And entire passages of his choreography demonstrate how, in his version of Lake, emotion and mood are disastrously—you might say heinously—neglected. (Forget about, for instance, the traditional “my mother’s tears formed this lake” mime in Odette’s explanation of her plight to Prince Siegfried. It’s gone. Disappearance, such as the now customary one of Benno, Siegfried’s best friend, has been extended to blood relatives.

Despite the fact that so much was missing, the house was not merely packed but eager to express its enthusiasm, if one could judge by the applause (with which today’s audience has become a naively used addiction.) Balanchine, in his occasional jokester mood, was known to comment wryly, “Call any ballet Swan Lake and people will come.”

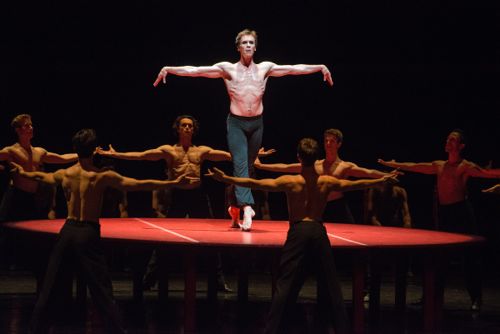

Only the presence of Sara Mearns, whose style has a profound visceral quality, made good sense of the double role of the pure Odette (a young woman captured and turned into a swan by an evil sorcerer, then forced to join a bevy of young women with the same terrible fate, as well as her evil opposite, Odile, the sorcerer’s daughter, who seduces Siegfried so that he’s tricked into taking the Bad Girl for the Good Girl).

Not since Suzanne Farrell has the City Ballet harbored the enormous imaginative resources of a dancer like Mearns, who played the double role on opening night. This is not to say that the two dancers are anything alike. (Every member of the highest grade of ballerinas is, obviously, sui generis.) Farrell was first and foremost an angel, a dancer whose very persona indicated qualities of the unworldly—indeed, the sublime. Mearns is a dancer whose feet (and instincts) are rooted in an imaginary earth. Again and again, in any of her performances, she reminds you that she is not a “ballerina” but a “dancer,“ in the way that Soledad Barrio and other greats of Terpsichore’s many-faceted realm are more than practitioners of a particular codified form of dancing.

Mearns’s dancing has an animal quality, revealed most fully through her strong, pliable spine and eloquent arms and hands. Whenever she dances—even in an abstract ballet—it tells a “story,” if not a narrative one. If there’s a dance equivalent to “reading the phone book,” that’s what I’d be willing to observe Mearns doing. Whenever I see her perform, I feel I’m looking at a marvel.

At the close of the NYCB performance, the littlest observers were carried to one of the theater’s exits, asleep, in the arms of their dads. It was way past their bedtime of course. But if some of these toddlers and kindergartners are eventually going to constitute a new generation of classical-dance fans—or even become professional dancers themselves, I hope they will eventually see versions of Swan Lake that do justice to the great ballet’s makers and its composer.

I recall, fondly, a little girl who wasn’t even walking yet, but sat on her living room floor spontaneously devising her own choreography (largely from the waist up) to the Swan Lake music playing on her family’s radio. She had not been told much of the story, but Tschaikovsky offered her enough to ignite her imagination.

© 2013 Tobi Tobias