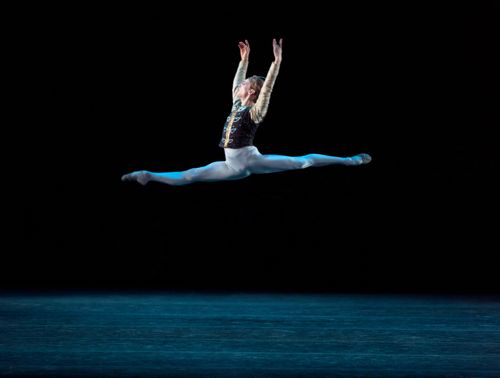

Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo / Joyce Theater, NYC / December 18, 2012 – January 5, 2013

The trouble with the Trocks—Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, the men-only troupe that parodies classical ballet—is that their dancing gets better and better. None of the dancers is qualified for a place in the higher echelons of the profession, but their technique continues to advance. Placement, the backbone of ballet, is given reverent attention, although the performers clearly need to have had more rigorous training when they were adolescents. The knees are sublimely taut. The pointe work, rarely the domain of men, has made amazing (and unlikely) progress. Here and there elevation is becoming—well, genuinely elevated. The phrasing is more musical, so that the dancing looks more like dancing rather than clowning around. And the company’s feeling for the essential absurdity of classical dancing is subtly and lovingly delivered.

A fatal moulting

A fatal moulting

Photo: Gene Schiavone

On opening night the company offered two takes on the iconic Swan Lake. The first derived from Act II of the original—the encounter of Prince Siegfried with Odette, a lovely maiden captured by a malevolent sorcerer and turned into a swan to reign as queen over a bevy of his victims, and then the virtuoso pas de deux in which the dangerously innocent young hero, yearning for pure, perfect love, mistakes the sorcerer’s wicked daughter, Odile, for his true soul mate.

The “Black Swan” pas de deux—an Olympic-style seduction of the innocent hero by Odile pretending to be Odette—offered a stunning account of the fouettés and several other showy challenges that gave the public considerable amusement and joy.

Every person in the company has a stage name, of course. Roberto Forleo, who plays Odette marvelously, is called Marina Plezegetovstageskya. Given the Trocks’ increasing sophistication, the humor is too broad. The dancer, however, quickly became one of my favorites in the group; she has the most ravishing line. The quartet of “little swans,” dancing, arms linked, in (well, almost) perfect unison, deserved medals for combining the frisky with the neat.

I should mention that, in addition to the traditional costume involving many white feathers, the Trocks’ Odette wears elbow-length white gloves—and somehow this additional accouterment seems perfectly natural.

Go for Barocco, choreographed by Peter Anastos in 1974, is the Trocks’ Balanchine send-up. Although it dutifully gives you your fill of daisy chains, which Balanchine overused a bit, it’s nowhere near clever enough, not compared to what Balanchine himself could have created, probably in under 15 minutes, had he been asked to see what teetered on the edge of the absurd in his own work.

Laurencia, in its unTrocked version, is a ballet based on a seventeenth-century melodramatic play by Lope de Vega that was inspired by a real-life historical event. The ballet was created in 1939 by Vakhtang Chabukiani—a formidable male virtuoso who defined the “heroic” style. No one ever kicked sand in this fellow’s face! The eponymous heroine of the piece is the feistiest girl you’d ever want to meet. No droit de seigneur customs prevail for her. There are still companies playing the piece straight, the Mikhailovsky, for one.

I must say that I had trouble understanding how the Trocks could successfully parody the ballet for an audience unfamiliar with the original, but these stylistically agile gentlemen, masters of broad, erotic humor, managed the job with their usual aplomb and contagious delight. Bringing faux-Iberian flair to a compact rendition of an afternoon in the village square (charmingly designed by Robert Gouge), the dancers combined bravura moves with similarly overwrought passions. Among the antics were a series of fouettés (whipping turns ideally coming in batches of 32, but, hey, who’s counting?) that had a spectacular finish and a batch of bourrées (tiny steps on pointe that travel sideways) that made every inch of the doer’s body quiver.

Since the original ballet was about conventional romance, many of the men in the Trocks’ version are playing men, a situation that induces some tantalizing confusion in the viewer’s gender-spotting. This may well lead, I dare to believe, to some useful enlightenment on the subject. Who would have thought that the Trocks were educational?

© 2012 Tobi Tobias