New York City Ballet: Premiere of Justin Peck’s Year of the Rabbit / David H. Koch Theater. NYC / October 5, 2012

Old-time followers of the New York City Ballet used to yearn for “another Balanchine”; today’s fans are more realistic. They count themselves lucky to discover “another Christopher Wheeldon”—an astute practitioner of the classical craft even if he doesn’t regularly fire the imagination. At 25, Justin Peck, a member of City Ballet’s corps, stands out in the crowd of aspirants to that status and has already achieved far more. Proof: his Year of the Rabbit, set to a score by Sufjan Stevens, which entered the company’s repertory on October 5, and is slated for three subsequent performances this season. Can it be just wishful thinking that I found it thrilling?

Justin Peck’s Year of the Rabbit for the New York City Ballet—full cast

Justin Peck’s Year of the Rabbit for the New York City Ballet—full cast

Photo: Paul Kolnik

In a September Works & Process program—part of the marvelous annual show-and-tell season at the Guggenheim Museum—Peck had delineated his own “process” in detail and at length until I, for one, wondered how dancing as I knew it could result from such a complex and mechanical system. They do say that Petipa worked out his choreography on a chess board, but Balanchine, equipped with his profound musical understanding, pretty much just walked into the studio and worked directly on the dancers. À chacon sa méthode. Peck’s method provided a skeleton for a brilliantly ordered dance for three couples: Ashley Bouder and Joaquin De Luz, Teresa Reichlen and Robert Fairchild, Janie Taylor and Craig Hall (the last pair rather more equal than the other two), and a corps that almost proved Peck’s desire—stated at the W&P event—to make corps and principals equal partners.

Ashley Bouder and male quintet in Year of the Rabbit

Ashley Bouder and male quintet in Year of the Rabbit

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Peck’s choreography for the three featured couples and a 12-member corps pushed City Ballet’s dancers beyond the extraordinary physical prowess we’ve already seen from them. The challenges of the choreography displayed their strength, speed, and daring, coupled with its opposite—control, which makes immaculate precision possible. Peck played ceaselessly with the idea of the individual in contrast to the group, not with the entities as rivals for the available space or the viewer’s attention but as partners in creating his singular world of youth at play and, inevitably, in love. Jerome Robbins’ Interplay, which now seems corny (and was always arch), might still be usefully thought of as Year of the Rabbit’s godfather.

Joaquin De Luz and trio in Year of the Rabbit

Joaquin De Luz and trio in Year of the Rabbit

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Most “emerging” choreographers fold references to their elders and betters into the new work they’re making. Like the best of them, Peck slips this sort of material into his own matrix with wit and understanding as well as admiration. Needless to say Balanchine is always there—as in the moment when the dancers are seen half in and half out of the wings the way they are in Symphony in Three Movements, but Peck has them lying supine, visible only from waist to crown. I enjoyed most the takes on Bronislava Nijinska—because they’re ingenious and beautiful of course, but particularly because they seize upon a school of classical dancing that is not part of the Balanchine legacy. (Peck is a product of the School of American Ballet, from which he moved directly into City Ballet.)

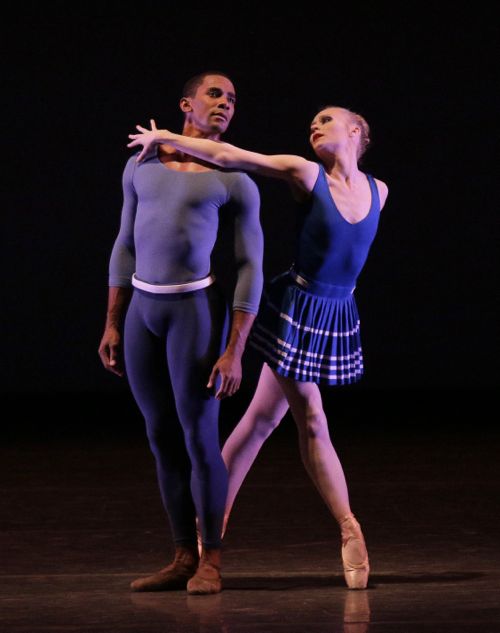

Craig Hall and Janie Taylor in Year of the Rabbit

Craig Hall and Janie Taylor in Year of the Rabbit

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Rabbit is structured within an inch of its life. The stage pattern, shifting like a kaleidoscope running on High, is always balanced—which would, of course, be wearisome if it weren’t arranged in such refreshing ways and rearranged every few seconds. The qualities of romance and its best friends, melancholy and yearning, make their appearance in several passages that are not as original or imaginative as the presto sections. They are workmanlike to be sure, occasionally touching, but I hope, one of these days, to applaud the moment in which Peck invites legato out on a date.

Throughout the ballet, Peck’s authority is evident. As is his earnestness of purpose. Both qualities will help him push forward. In time, if we’re lucky, he’ll allow the unplanned to expand what he’s doing.

Earlier this season, though unable to write at the time, I marveled at City Ballet’s rendition of Balanchine’s choreography in three programs devoted solely to the master’s work. I wondered then, as I have on several other special occasions, why the company allows lackluster performances when it can render the work with the empathy and brilliance it deserves.

A special evening was also devoted to honoring the fashion designer Valentino whose “costumes” can give a society woman marvelous éclat, but who doesn’t get—and why should he?—the very basics of ballet costuming. Valentino gave his “dancing girls” tutus in peculiar and unflattering shapes worn over white panties that might have come from today’s equivalent of Woolworth’s. The women’s legs were sheathed in tights in the dreadful pancake-makeup tint that, in bygone times, was supposed to represent Caucasian flesh. (To my knowledge City Ballet includes no African-American women.) The leg line—classical ballet’s hieroglyphic—was set afire at its tip by the inevitable red pointe shoes, red being the designer’s signature color. The effect traduces the Moira Shearer film that got it just right.

Anyone will tell you that these gala evenings are not meant for the critics but rather for the company’s donors, as one of several means of inducing them to keep up their much-needed, much-appreciated financial support. But what could we learn from the Valentino evening—that wealthy patrons of the company, communally, have tawdry taste?

© 2012 Tobi Tobias