New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 15 – February 24, 2013

The New York City Ballet opened its six-week Winter Season at Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater with George Balanchine’s Serenade, created in 1935 and set to Tschaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings. It was the first ballet the choreographer made in America. (In the two weeks immediately following, the company’s repertory is devoted—with a single exception, a new work by Peter Martins—to this extensive and often felicitous pairing of composer and choreographer.

The New York City Ballet’s Sara Mearns, airborne amongst her sisters, in George Balanchine’s Serenade

The New York City Ballet’s Sara Mearns, airborne amongst her sisters, in George Balanchine’s Serenade

Photo: Paul Kolnik

I saw my first Serenade back when the New York City Ballet was still performing at the New York City Center. “The people’s theater,” the then-dingy auditorium was called—meaning that even my schoolgirl allowance could cover the price of a ticket. Back then, as I recall, each season opened with Serenade. The ballet was already an icon—ravishingly beautiful, poignant in ways dependent on how you interpreted it, enormously inventive, and a statement of intent—a model of what a Balanchine ballet could be.

Regular members of the audience would then notice changes Balanchine had made in the choreography since the last season and boo them softly under their breath. How dared he? we were asking—and then remembering, with some embarrassment, that Balanchine, its maker, not his already ardent audience, owned it. But for those of us faithful watchers, it was as if a living being had been ruthlessly altered; season after season, it took us a while to get used to the “latest” Serenade.

The second-night performance of Serenade in the current season featured Sara Mearns—much missed last season because of an injury—who was making her debut in the ballet. Her talent is so prodigious, she’ll unquestionably be wonderful in the role; she’s already unforgettable. Like Suzanne Farrell, she imprints herself indelibly on the viewer’s perception. But, to my eyes, she still seems to be figuring out what the ballet is “about.” I’m eager to see further performances that will reveal her development of who and what she can be in the role.

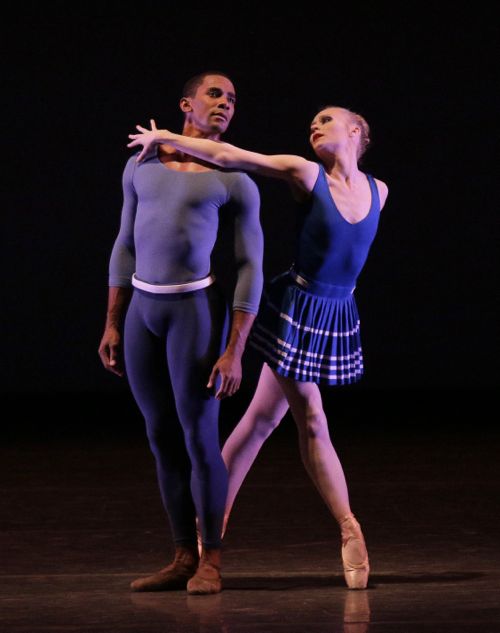

Sterling Hyltin and Chase Finlay, making their debuts in the central roles of Mozartiana

Sterling Hyltin and Chase Finlay, making their debuts in the central roles of Mozartiana

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The program moved on to an engaging rendition of Mozartiana led by Sterling Hyltln, Chase Finlay, and Anthony Huxley. Every season reveals Hyltin’s progress in the combination of delicacy and strength that makes us think of porcelain. Is it unreasonable to wish that she might develop a hint of a tragic dimension as well? Finlay is still a so-so partner, whose gradual improvement deserves to be coddled because he’s such a gifted and engaging dancer. He has a reasonably gracious partnering manner, but he’s still somewhat deficient in the coordination part of the job.

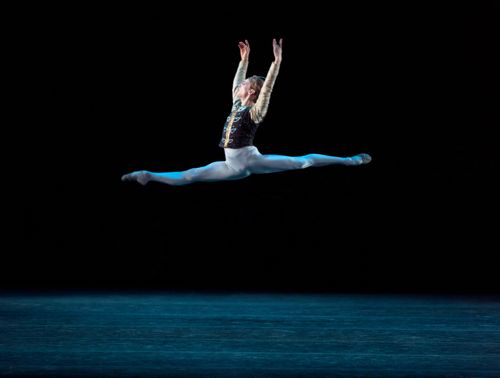

Anthony Huxley, one of the City Ballet’s several young men fulfilling their early promise, performing the Gigue in Balanchine’s Mozartiana

Anthony Huxley, one of the City Ballet’s several young men fulfilling their early promise, performing the Gigue in Balanchine’s Mozartiana

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Huxley offered the best account I’ve seen of the jester role, as I think of it, in a long time; he just needs to “throw it away” more so that you realize his character comes from the noble art of clowning. The whole ballet was meticulously danced as if, indeed, it had been meticulously rehearsed—not always the case at City Ballet, which frequently sacrifices polished renditions to presenting a large repertory. Balanchine himself had mixed emotions about “correctness.”

Teresa Reichlenand and Tyler Angle, icons of royalty, in Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2, formerly known as Ballet Imperial

Teresa Reichlenand and Tyler Angle, icons of royalty, in Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2, formerly known as Ballet Imperial

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2, which closed the program, was presented, rightly, as a compelling, large-scale event that, alone, would prove the company’s right to top-drawer status in the classical ballet world. Actually, it presents a world in itself—so convincingly varied yet cohesive, it arouses complete belief. The company happily managed this effect with grace and musicality as well as grandeur. Teresa Reichlen, who danced the critical female role, still needs more experience in roles requiring ballerina authority—just now she’s wonderful but somewhat too reticent. Her modesty is refreshing, though; it’s a virtue our culture honors all too rarely. In fashioning the choreography, Balanchine seems to have used everything he learned from Petipa and then doubled it in terms of invention, complexity, and sheer crowd control. The piece got more and more thrilling as it went on, all the while inviting—no, urging—its viewers to watch more keenly than ever.

© 2013 Tobi Tobias