Paris Opera Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 11-22, 2012

Say that, as a dance fan, you happen to have a young child in your life who’s showing a burgeoning interest in—perhaps even an instinctive love for—dancing. If you take her or him to the ballet to see one of the venerable 19th-century classics, you want to be sure it’s a production that’s faithful to its tradition—not savagely cut, skewed, or “reimagined” beyond recognition. The very young, with their acute receptivity, deserve the very best.

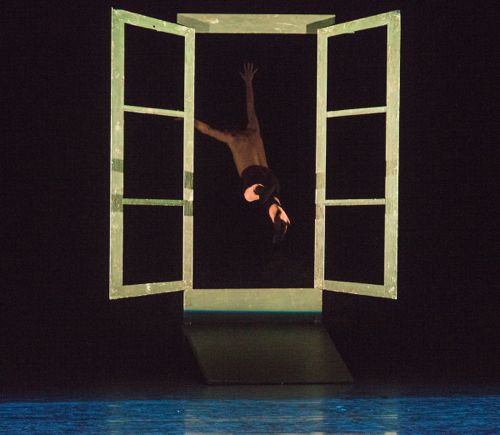

The Paris Opera Ballet’s Aurélie Dupont in the title role of Giselle, with the corps de ballet as wilis

The Paris Opera Ballet’s Aurélie Dupont in the title role of Giselle, with the corps de ballet as wilis

Photo: Stephanie Berger

I’ve had the pleasure and responsibility of fostering such a dance-avid child’s interest in ballet for a dozen years. (She’s 15 now—a scholar, a musician, and a runner.) We’ve had the luck of living in New York City, host to American Ballet Theatre, the New York City Ballet, and a plethora of ranking visiting troupes. As time went by, though, there was a diminishing number of satisfactory productions to be seen of touchstone works such as The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake.

Happily, the current visit of the Paris Opera Ballet has brought us the most beautiful and satisfying staging of Giselle that I’ve ever witnessed—and I, too, fell in love with ballet very young (without the help of a fairy godmother). Created for the company in 1841, this is a Giselle that sets the ballet where it belongs—in a pastoral community glowing with sunshine and good will until a dallying prince invades it (his excuse, he claims, is love), then in a dank graveyard populated by vengeful ghosts who can be vanquished only by a devotion existing beyond death (even then it’s a damned close call).

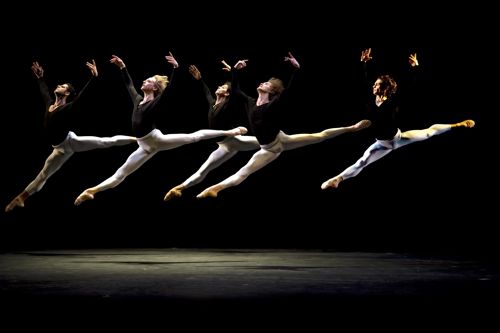

Dupont as Giselle, Mathieu Ganio as Albrecht, and the corps de ballet

Dupont as Giselle, Mathieu Ganio as Albrecht, and the corps de ballet

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Unusually, this production of Giselle is not entirely dependent on the ballerina playing the title role. Indeed, the work of the corps de ballet, 26 women, moving as one, creating one breathtaking sculptural image after another, is of equal—perhaps greater—importance. The interlacing lines of wilis (maidens who’ve died when their sweetheart betrayed them) crossing the stage in traveling arabesques made me gasp along with the neophyte viewers, though I’d seen the passage again and again. The stunning effect of the corps is no doubt due to the strict principles governing the dancers’ selection, their scrupulous training from childhood through adolescence (with many aspirants falling by the wayside) and, somehow, to their apparent communal dedication to animating the choreography at the highest level possible. It’s a zeal that never flags but is, instead, renewed night after night. I find all of this eerie and marvelous and feel privileged to witness it.

The costumes for the production, after those designed by the celebrated Alexandre Benois in 1924, are ravishing. The lower classes are modestly dressed. Then a procession of the aristocracy (to which the unreliable prince belongs), on its way to the hunt, brings rich color and magnificent detailing—in more or less medieval style—into the picture. The palette includes bright red, crimson, mulberry, violet, peach, cream, and deepest blue, the last offset with ermine trim. The complementary headgear is appropriately outré. Every last one of this 1% looks haughtily stunning.

In the second act, however, the wilis’ nearly surreal white costumes make the gorgeous worldly outfits we saw on the aristocracy look like mere gaudy outer skins of the earthly upper class. The wilis are clad in the uniform of their mystical if horrific rites. The ghostly women, veiled when we first see them, wear neat bodices above long tutus that flair out in quivering concentric circles when the women turn, as if creating a gently whirling cloud around their legs. From the back of their bodices sprout tiny translucent white wings. Where are they going to fly, I wondered, if they’re essentially dead and buried? No matter; once the second act is launched, susceptible observers will have entirely suspended their disbelief. They’ll see nothing but a stream of miracles.

Even the lighting of this Giselle is magical, most obviously in the slow coming of dawn, which robs the wilis of their power, saves the now-repentant prince’s life, and sends Giselle back to the sorrowful and lonely peace of her grave. It’s a peach-tinged light, a glow really, that increases as subtly as sleep finally arrives to an fretful insomniac.

As I write, I’ve seen three of the POB’s Giselles (and am signed up to see two more). By far the most gratifying was the first of them, Aurélie Dupont (whom I couldn’t resist visiting twice). The others were Clairemarie Osta and Isabelle Ciaravola.

Dupont is not the first ballerina you’d identify with Giselle. She has a devastating personal beauty (not necessary for the role, maybe even distracting) and an authoritative presence, no doubt encouraged by her years as an étoile–the A+ dancers of the company, according to its hierarchical system. Yet, as POB’s aesthetic dictates, she doesn’t “sell herself” but rather underplays and, in doing so, entices the viewer to join in the work of her imagination.

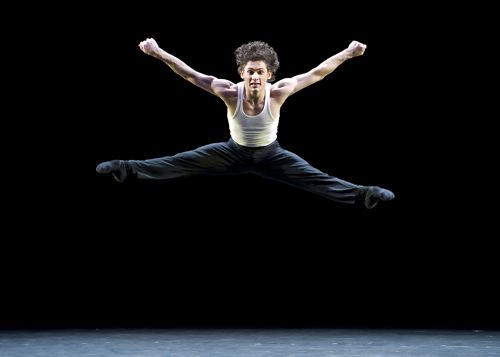

Dupont (center) as Giselle

Dupont (center) as Giselle

Photo: Stephanie Berger

In the first act of the ballet, her work is initially impressive only in the fluency and correctness of her dancing. But she’s a master of calibration and when she arrives at the Mad Scene she takes fire. First she looks like a child betrayed, then sketches the history she’s recalling of Albrecht’s (as the two-timing prince is called) courtship of her—making each feeble, jagged gesture a stab to the spectator’s heart, then leaping wildly here and there, as if to escape her sorrow.

Her second act was beyond terrific, her personal glamour sacrificed to create an image that was all air and pathos. She danced and acted as if those two elements might, quite naturally, be tethered to each other. At the moment of her appearance at the command of Myrtha, queen of the wilis, whirling as if seized by some untamable force of nature, she seemed to be a dead soul. Then, gradually, she achieved a piercing half-life through her memory of a love that refused to acknowledge death. She reacted to the now penitent and sorrowing Albrecht as if she didn’t actually see him and couldn’t really touch or be touched by him, yet somehow, deep within her senses, recalled an attachment to him that she would never abandon.

Dupont and Ganio as Giselle and Albrecht

Dupont and Ganio as Giselle and Albrecht

Photo: Stephanie Berger

In all this, she displayed two gifts essential to a ballerina: She makes you look at her (indeed refuses to let you look away) and she makes you believe in her.

Clairemarie Osta is a marvelous dancer—fresh, fleet, and buoyant. She’s no stranger to virtuoso feats where they’re appropriate. For one thing, she does the diagonal of hops on pointe traveling backwards—without in the least seeming to show off. Her Mad Scene has personal touches that are entirely apt. Overall she plays it as if she had slept while the prince-playing-peasant courted her and she responded with shy joy, and has now awakened to a nightmare. And yet Osta’s never entirely convincing as Giselle because she’s just not the type. She doesn’t come across as a fragile, vulnerable young woman to whom tragic things happen. She has the delicious personality of a soubrette; a born Lise in La Fille mal gardée.

Isabelle Ciaravola didn’t endear herself to me in L’Arlésienne and my lack of enthusiasm continued upon seeing her Giselle. Like her fellow étoiles she is amazingly capable. Still, the rank of étoile is supposed to be given for a charisma, a luminescence that is beyond technique. Instead I find Ciaravola dry, angular, even occasionally grotesque, as if she were activated by an unreliable puppet master maneuvering the strings. I’d prefer not to be so negative—especially about a dancer I’d never seen before now—but I understand, just from intermission talk, that she has many admirers, so if I can’t see what’s terrific about her, no matter. That’s the beauty inherent in having a diversity of dancers to interpret a role. The Parisians fielded four in New York and, with three of these close to retirement, no doubt have other candidates back home.

None of the Albrechts I saw seemed just right for the role, one too young and brash paired with a mature ballerina; another too mature to negotiate the technical challenges, though theatrically wise; a third who, with everything going for him, remained indifferent to the story the ballet means to tell. The men’s partnering, though, particularly in the second act, never faltered.

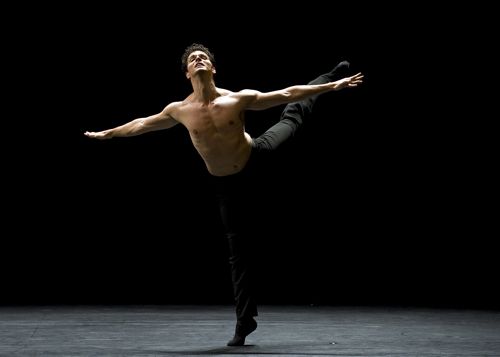

Marie-Agnès Gillot as Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis, in Giselle

Marie-Agnès Gillot as Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis, in Giselle

Photo: Stephanie Berger

As Myrtha, I much preferred Marie-Agnès Gillot, who alone had the force the role demands and a rare range of emotion. Gillot is one of the most versatile and impressive dancers in the august French company, and her presence permeates the entire second act—until Giselle’s literally undying love for Albrecht defeats her. Emilie Cozette, the first-cast Myrtha, was sweet, small, and tender. What had Casting been thinking of?

Apart from the excellence of the dancing, the company’s style in mime is ideal. Even when it’s in the traditional code vocabulary (for example, tracing a circle around the face means “beautiful”), it’s very underplayed—conversational, as it were. The POB dancers behave as if dancing were their poetry, mime their prose, and the two were intimately related. Think of the relationship between aria and recitative in opera.

The corps de ballet as wilis

The corps de ballet as wilis

Photo: Stephanie Berger

A minor but telling detail (one of many, the Parisians being well-nigh obsessive about detail): Just as in the lithographs of Romantic Age ballerinas, the wilis carry their heads inclined slightly forward, drawing attention to the back of the neck (la nuque, in French)—a part of the body that, according to Japanese culture, is considered particularly beautiful and erotic. Evidently, the Japanese are right.

Led by the Belgian conductor Koen Kessels, the orchestra of the New York City Opera delivered Adolphe Adam’s score sensitively and vibrantly. Ballet music is rarely so well treated in New York. It was a pleasure to hear what’s possible, given care and financial support.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias