Paul Taylor Dance Company / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / March 13 – April 1, 2012

What dance company director could resist the opportunity of playing the grand-scale Lincoln Center house formerly known as the New York State Theater, even if his or her usual venue were the now handsomely refurbished City Center? Not even Paul Taylor, who has firm, if sometimes oddball, principles. The Paul Taylor Dance Company seized the opportunity to perform there for three weeks and the people in charge of such things shrank the space and overlooked the fact the company couldn’t afford live music.

Michael Trusnovec and Laura Halzack in Paul Taylor’s Aureole

Photo: Tom Caravaglia

Black masking reduced the stage space from its New York City Ballet proportions (it was built primarily to serve Balanchine). It diminishes the height and width of the proscenium and thrusts the wings closer to center stage. I believe the cyclorama at the back of the stage has been moved forward too. The job has not been done with any imagination or grace and certainly with no luxury; it cheapens the frame in which the dance is the picture. Throughout the repertoire, the lighting has been inexplicably dusky, and the canned music sounds tinny. Some of the choreography looks OK in this venue; more of it doesn’t, though the company will adjust to the space as good dancers typically do. When it comes to Taylor’s dancers and Taylor’s dances, however, we’re not talking about plain old good. We’re talking about “frequently glorious” in both departments.

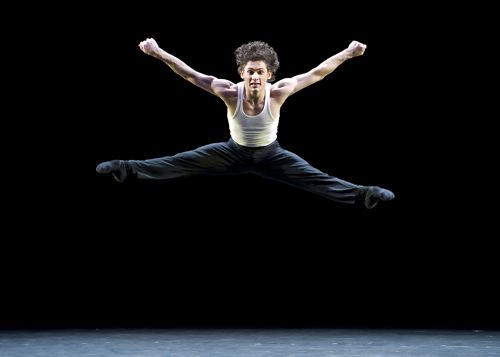

Michelle Fleet in Taylor’s The Uncommitted

Photo: Tom Caravaglia

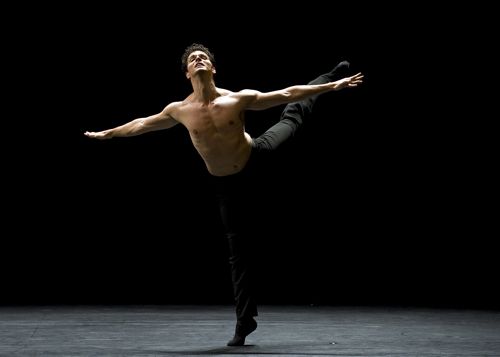

The repertoire for the season is incredibly rich in the masterworks created by Taylor over a half century. New to New York was The Uncommitted, set to music by Arvo Pärt, a favorite with choreographers given to exploring the poignancy of human existence. It describes a world populated by people who are pathologically unable to respond to society’s urgent message—“Only connect.” At first the eleven dancers move in a vocabulary that is largely a single gesture or, at its most generous, one little dance phrase after another. They’re not even a community, just unnervingly separated individuals occupying a shared space. Taylor also calls on an old trick of his: a group of dancers moving in a circle looses one of its members to take a central position, and then replaces him or her with another figure from the circle. Rarely can you see the switch happening; it seems to occur by magic. The person caged at the center is also deprived of fluency, managing to execute only a fragment—a shard, really—of dancing. The sole exception to this paralysis is Michael Trusnovec; everything he does, even standing in repose, looks like dancing.

The isolated movers next join in duets and trios—brief ones, however, as if the participants can’t sustain the contact involved in moving with another person. This section is beautiful and filled with pathos. Two pairs switch partners as if it doesn’t matter whom you dance with, whom you mate with, whom you love (if, indeed, you know what love is). Trusnovec and his partner, Laura Halzack, are granted a long duet but can’t seem to get it together and end, inevitably, by walking away in opposite directions.

Halzack and Trusnovec in The Uncommitted

Photo: Tom Caravaglia

A final section has the crowd of 11 walking aimlessly around and, if they make eye contact, immediately turning away. A woman adrift in a crowd has no boundaries, no destination, no one even to recognize her presence. The crowd travels back and forth, cross stage, peeling off one by one and disappearing. Halzack, the last person left, watches the man she has finally identified as her guy vanishing into uncharted territory and yearningly stretches out one arm in his direction.

Taylor’s treatment of the social alienation theme is a little pat, a little corny, and certainly déjà vu. The Uncommitted is interesting in its first section as an exercise in unlinked motion. From the earliest days of his career, Taylor has been fascinated by—and ingenious in exploring—how much you can subtract from conventional theatrical dancing before things fall apart. But, as a whole, the piece is not compelling in terms of feeling.

Halzack, Michael Novak, and Michael Apuzzo in Taylor’s House of Joy

Halzack, Michael Novak, and Michael Apuzzo in Taylor’s House of Joy

Photo: Paul B. Goode

A second work, House of Joy (i.e., whorehouse), being given its world premiere, is just nine minutes long and registers as the introduction to a dance that has yet to be (if you’ll excuse the wordplay) fleshed out. It has a large cast (of 12) garbed by Santo Loquasto in his familiar picturesque vein plus a set, also by Loquasto, in forced perspective, of a street in a run-down part of town. The players are three procurers who apparently scour the mean streets for randy guys who can pay for satisfaction; four clients—one of them a petite but feisty woman; and a quintet of “Shady Ladies,” one of them male. One after the other, boy meets girl, so to speak—one of the guys is a fussy geriatric—and then the curtain comes down. Huh?

Is Taylor’s genius so forbidding that he has no buddy who might have said, “Fill ‘er out, Paul, or let ‘er go”?

I didn’t get to see Gossamer Gallants, a third Taylor effort new to New York. I understand it’s a goofy gloss on Jerome Robbins’ The Cage. It will have to keep. There are, as urbanites complain, only a certain number of hours in a day. In this heady dance season, aficionados are finding that those are already double-booked.

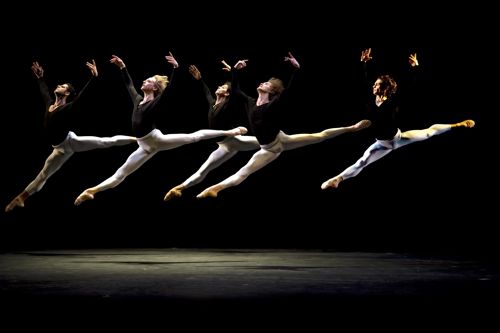

The original and current casts of Aureole bowing after the 50th anniversary performance of the dance

The original and current casts of Aureole bowing after the 50th anniversary performance of the dance

I did see the 50th anniversary performance of Taylor’s Aureole, one of the dance world’s loveliest classics, which, coupled with the faux-spring weather of the week, yielded a message about life’s being worth living. At the curtain call the originators of all the roles—Elizabeth Walton, Dan Wagoner, Sharon Kinney, Renée Kimball, and Taylor—bowed with the performers of the present, giving the audience a visual metaphor for the unbroken link between then and now.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias