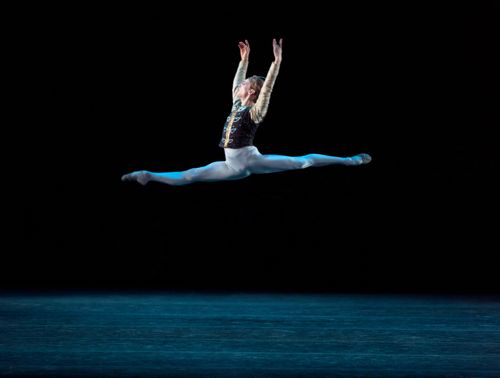

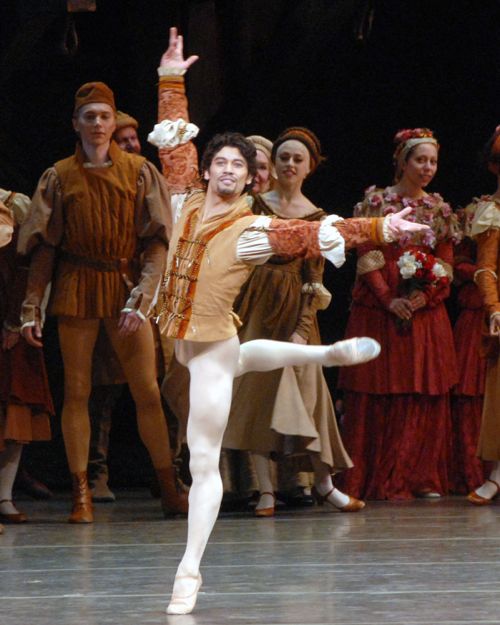

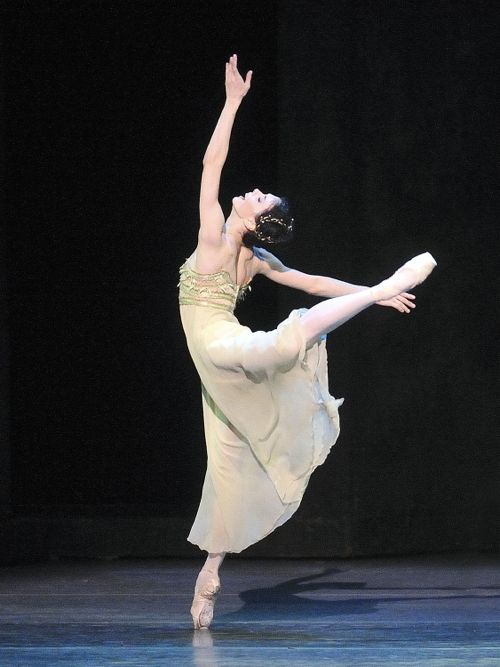

American Ballet Theatre: Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, with Natalia Osipova, David Hallberg, and Herman Cornejo / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 18, 2012

The near-hysterical joy of the audience at the Metropolitan Opera House on June 18—in response to American Ballet Theatre’s pairing of Natalia Osipova and David Hallberg as the leads in Romeo and Juliet—was a theatrical phenomenon in itself. The star-struck approach to ballet is hardly the only one to take; it may even be thought frivolous. But it can certainly make a performance vivid and powerful, all the while doing the essential job of selling tickets. (The house was packed.)

Natalia Osipova and David Hallberg in American Ballet Theatre’s production of Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet

Natalia Osipova and David Hallberg in American Ballet Theatre’s production of Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet

Photo: Gene Schiavone

On this occasion the casting in Kenneth MacMillan’s 1965 three-acter—to the Prokofiev score that, mood by mood, almost tells the story borrowed from Shakespeare in itself—was made super-effective by the inclusion of Herman Cornejo as Mercutio. Depleted as the company is of stars who’ve emerged from its ranks or are, at least, a full-time part of its roster, the abiding presence of Cornejo is something for which ballet lovers should be down-on-their-knees thankful. Is he still present because of loyalty? Dancing is such a precarious trade that its practitioners can’t afford too much loyalty. More likely is the fact that the fates have made this extraordinary artist a couple of inches shorter than is customary in a danseur noble.

Herman Cornejo as Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet

Herman Cornejo as Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet

Photo: MIRA

Cornejo’s dancing is phenomenal partly because of its correctness, to be sure. Everything he does is immaculately shaped and harmoniously placed, resulting in a succession of images—each with its particular texture—that you can envision days after the performance. But while you’re watching him, you don’t much dwell on that aspect of his work even though he makes the individual steps link together, forming rhythm-blessed phrases. The miracle of Cornejo’s dancing is that he makes what he’s doing look natural, like something an ordinary young man who goes in for sports might do. No matter what the challenges of strength, form, or sheer coordination, even when the choreography is charged with near-impossible feats, Cornejo’s dancing remains utterly human.

The team of Hallberg and Osipova is especially potent because each of them fuels the other, though they don’t even have fluency in a spoken language in common. Their communication seems to be intuitive and, when they play against each other, they’re able to fill the stage with feeling that seems spontaneous. One acts, the other reacts, and everything—including the narrative that begins in sudden rapture and ends in a desperate dual suicide—is activated as if for the first time. Without this factor, the superlative technique each of them possesses wouldn’t be entirely satisfying. (In the arts, technique alone never is.)

Osipova as Juliet

Osipova as Juliet

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Osipova seems to have thought out her motivation for each phrase of her role and renders it clearly. Even if you disagree with her interpretation at moments, you see what she means. And the details are many: When Juliet’s nurse tells the barely nubile girlchild that she must stop playing with her doll and cups the girl’s budding breasts, Osipova’s Juliet is one second in denial and in the next shyly pleased by this sign of burgeoning womanhood. From then on, we see Juliet discover, step by step, what love is—a supreme joy, yet capable of ruling over one’s entire existence and, in her case, possibly fatal. Osipova is haunting as well in conveying how bereft of human support Juliet has become by the time she accepts Friar Laurence’s potion for a death-like sleep, terrified that she make never wake again. That state of being alone has a very contemporary significance and Osipova makes it ring all too true. This was an eye-opener for me since, before this performance, I’d never thought of this dancer as a ballerina, the figure who can give a ballet a heartbeat. Albeit belatedly, now I do.

Hallberg begins the ballet as a dreamy youth in love with love. He runs after the sleek beauty Rosaline as if he were a puppy, or an infatuated teenager, which is just what he is. When he sneaks into Juliet’s coming-out party with his two best buddies, he’s simply a young guy having fun by breaking society’s rules and courting danger. Scene by scene, though, he matures; by the time the ballet ends, he has attained a grave and touching manhood. In the final scene, he evokes a very plausible agony, displaying a visceral as well as an emotional reaction to his belief that the perfect love he’d yearned for, and found, was now dead.

Hallberg as Romeo

Hallberg as Romeo

Photo: Gene Schiavone

As for the pure dancing aspect of his role, Hallberg is surely the most exquisite danseur noble on the stage today. In the balcony pas de deux, he dances with a princely perfection, almost entirely confident that Juliet is as smitten as he.

He turns Osipova’s incomparable lightness into something far more than a breathtaking physical phenomenon; it looks like a statement of how he makes her feel. Working together, if these two don’t convince you of the validity and power of teenage love, I can’t imagine who or what might.

What the couple fails to do is cope with MacMillan’s impossible lifts. (In another R & J cast this season, I saw the Royal Ballet’s infinitely appealing Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg bring off each one perfectly, so now I know it can be done. They’re both with the Royal Ballet, so maybe they get a lot of practice.) Nevertheless, what I’ve seen in several ballets recently is that Hallberg is still, physically, a mediocre partner. He has a rich and persuasive imagination, but it comes across best when he’s dancing (and dreaming) alone. Dancing as the suitor of a woman his character yearns for, he’ll get the emotional tone of a relationship just right, but he hasn’t yet perfected the mechanics of it.

Still, there was so much in this performance to marvel at, the peculiar latter half of the third act came as a rueful surprise. What went wrong? Well, in the first two acts, there were a lot of subtle adjustments to the choreography that could be explained away as “interpretation.” In the third act the Osipova/Hallberg dream-team was enjoying a kind of emotional free-play that reduced the audience to the status of voyeurs. The two dancers rely for much of their effect on an instinctive emotional and theatrical communication. This state of affairs can result in glorious performances—the kind you expect to tell your grandkids about. (Fonteyn and Nureyev come to mind. Sorella Englund playing the witch in La Sylphide to Nikolaj Hübbe’s James.) But who is to say where the line should be drawn? In this case I drew it when the dancing moved out of the realm of classical ballet.

Osipova and Hallberg in the title roles of Romeo and Juliet

Osipova and Hallberg in the title roles of Romeo and Juliet

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Enormously gifted, both Osipova and Hallberg have been trained to the highest degree in present-day classical dancing. Nevertheless they’re innocents when it comes to the kind of modern-dance vocabulary they seemed to be co-opting as the lives of the young lovers they played disintegrated. Suddenly the dancers’ bodies were reaching with frantic arms; writhing from the gut; flinging themselves, uncontrolled it seemed, into space; hunkering down as if to crawl their way to their terrible ending. Nearly inchoate, they were unconvincing. They resembled nothing so much as a bunch of preteens in a “creative dance” class, the dubious purpose of which was translating emotion into a graceless form of “animal behavior” (an ironic expression, since animals are naturally graceful). In the final scene, in the tomb, when Juliet awakened from Friar Laurence’s sleeping draught and contorted her face into a Munch-like scream, I decided that matters had definitely gone awry. This is nothing to complain about, really. As Blake wrote, “You never know what is enough until you know what is more than enough.”

Several of the ballet’s character roles were beautifully conceived. Susan Jones has long made a memorable impression as Juliet’s nurse, all motherly love tempered with down-to-earth practicality. Every bit of her behavior enlarges the portrait—the slow, rhythmical beating of her fists against the floor, for example, when Juliet, about to be married against her will to Paris, is discovered in her bed, seemingly dead.

Kristi Boone a smart, strong dancer with a flair for creating a character, continues to be an important—though not sufficiently recognized—asset to ABT. As Lady Capulet, Juliet’s mother, she accounts boldly for every feeling the woman has: pride in her social position; a claim to authority over her daughter, mercifully undermined, after all, by a mother’s love; unbridled passion for her lover.

Victor Barbee, whose dramatic-dance performances are packed with significant detail, played a steely Lord Capulet. As early as Juliet’s coming-out ball, he was shooting his gaze here and there, rightly suspicious that his wife was betraying him with Tybalt, his young daughter’s fiery cousin.

No one will ever replace the veteran artist Frederic Franklin as Friar Laurence but, having recently reached the age of 98, he has relinquished the part. The choice of Alexei Agoudine as his successor is a sound one. Agoudine has the perfect face—sober with belief—of a monk with only good intentions.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias