Paris Opera Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 11-22, 2012

The Paris Opera Ballet, playing at the David H. Koch through July 22, gets the prize for vintage achievement. Formed in 1669, it has the distinction of being the world’s oldest classical ballet troupe. The academy that produces most of its dancers dates from 1713. Naturally, this legendary institution, absent from New York for 16 years, had to re-introduce itself.

The Paris Opera Ballet’s Aurélie Dupont (center, held aloft) with fellow artists of the company in Serge Lifar’s Suite en Blanc

The Paris Opera Ballet’s Aurélie Dupont (center, held aloft) with fellow artists of the company in Serge Lifar’s Suite en Blanc

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The first of the three ballets it performed on its opening night in New York declared that exquisite technique rules the company’s aesthetic. Serge Lifar’s Suite en Blanc, set to Édouard Lalo’s score for Namouna, is essentially a compendium of steps, steps immaculately executed by the dancers—almost all trained at the company’s school from early childhood—so that they seem to be the definitive, textbook, version of that step. The goal is, quite simply, perfection. Onlookers will find this sublime, curious, or off-putting, according to their taste. As for its being a ballet about ballet, it’s a distant cousin of Harald Lander’s Études, often performed by American Ballet Theatre, but neither gaudy nor wild. Suite en Blanc is completely confined within the parameters of good taste.

Some, almost random, particulars:

The women’s feet—in their spanking clean, neatly tied pink satin pointe shoes—seem to caress the stage floor and, incredibly, make no sound on the landings from jumps and leaps or on gentle pitter-pattering runs.

The women’s arms are graceful and ornamental, tracing filigreed patterns on the air. The head, neck, and shoulders harmonize scrupulously to produce an effect called épaulement, something Balanchine ignored, because it interfered with the speed he wanted and, perhaps, because it looked old-fashioned.

There are women who can balance forever on one foot—en pointe, of course—turning themselves into an unwavering middle-weight piece of sculpture, apparently through sheer will or perhaps a code of honor.

Everyone in the company, it seems, can turn like mad, some even like gyroscopes. Among the men the finishes—always the telling part of a turn—are sometimes uneven.

The men bend their knees slightly and shoot their bodies directly up into the air, beating their feet together, clearly and firmly, then landing neatly. Missteps, even on a first performance in an unfamiliar theater, are few and clearly destined for eradication.

The men are not only adept partners, but also infinitely polite and respectful cavaliers as well. And they manage to pull off impressive athletic feats without looking like cavemen. True this unremitting chivalry and control may exasperate the New York spectator. We’re simply not used to it.

Throughout, there’s not much variation in the weight of a step. Even in the air, the dancers don’t create the illusion of being ethereal—or, on the ground, impressively forceful. What they’re aiming for, I guess, is sublimity.

Aurélie Dupont and Benjamin Pech in Suite en Blanc

Aurélie Dupont and Benjamin Pech in Suite en Blanc

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The high point of Suite en Blanc is a duet in which I saw Aurélie Dupont, a ravishing dancer nearing the company’s compulsory retirement age of 42, sveltely partnered one evening by Benjamin Pech and the next by Mathieu Ganio. Dupont is undeniably a beauty—in both face and figure, a superb dancer with the lush quality of a Suzanne Farrell or a Sara Mearns, and a role model of calm, confident serenity. She exemplifies the rank of étoile (star)—which the company awards to those artists who have a luminous quality that draws viewers’ attention like a magnet and makes them rejoice in what they see. There’s a marvelous moment in the duet where the man walks forward holding her body above the floor and she “walks” too—on air. And another in which she lifts her arms over her head and intertwines her fingers as if to indicate at once the crown of a regent and the halo of an angel. If I had known about her earlier, I would have traveled to Paris more often.

Isabelle Ciaravola and Jérémie Bélingard in Roland Petit’s L’Arlésienne

Isabelle Ciaravola and Jérémie Bélingard in Roland Petit’s L’Arlésienne

Photo: Stephanie Berger

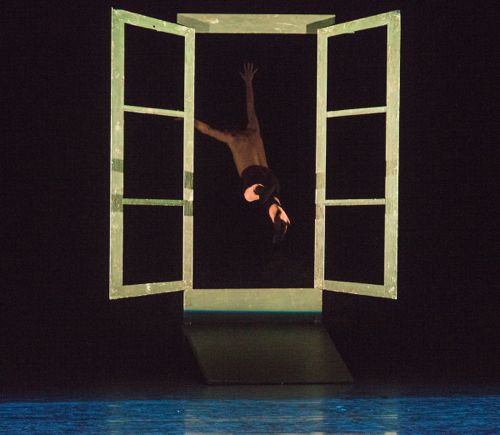

It took me a second viewing to figure out the tale Roland Petit’s 1974 L’Arlésienne was trying to tell and even then the story felt wrong-headed. The title itself, The Woman from Arles, appropriated from the Bizet score to which it’s set, is a red herring because the central figure of the ballet is a young man. He and the woman his fellow villagers—a 16-member corps—assume he will marry and settle down with, can’t make their relationship work because the youth has visions—visions of a love that’s utterly beyond earthly reach. Think of La Sylphide, in which James, slated to marry the charming, down-to-earth Effie, feels trapped in the ordinariness of his bride-to-be and the domestic life their community expects them to lead together, and so dreams of a love that’s literally unearthly. You know how that one ends.

The woman, played paper-doll style (is this how Our Hero thinks of her?) by Isabelle Ciaravola and more humanly and sweetly by Nolwenn Daniel, approaches her intended again and again—this is a tediously long ballet—and the two do try to connect, to no avail. He grows more and more possessed by his visions and allergic to her overtures and at last jumps out of a suddenly and conveniently appearing window to his death.

Jérémie Bélingard in Petit’s L’Arlésienne

Jérémie Bélingard in Petit’s L’Arlésienne

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The dancers I preferred in the leading roles were Jérémie Bélingard in the opening night cast—his acting was so convincing I almost believed in the goings on–and Nolwenn Daniel (who played a sweetheart any man would be proud to win) in the second performance.

Bolero: You know that Ravel music. And it’s still just as long as you remember. It belabors a simple melody, assuming that repetition, hand in hand with escalating volume and augmenting instrumentation, will hypnotize the hearer. The composer, it’s said, told a friend that he found the little phrase itself “insistent.” Apparently Bronislava Nijinska thought so too and was the first to choreograph the score, in 1928.

Nicolas Le Riche in the central role of Maurice Béjart’s Bolero

Photo: Stephanie Berger

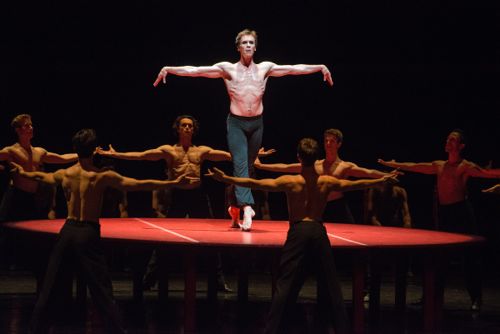

The Paris Opera Ballet does Maurice Béjart’s 1961 version. It’s an audience pleaser, god knows; I find it unbearable. The choreography features a man or a woman (I saw Nicolas Le Riche on opening night, Marie-Agnès Gillot the following evening), discreetly wearing as little as possible under the circumstances, standing on a red oval table to pulsate, gyrate, and gesticulate nonstop with increasing fervor. He (or she) is bordered on all three sides of the stage by a row of dancers who become drawn into the rite until, at the finish, they close in and lunge at the figure on the table, suggesting a synchronized orgasm.

Nicolas Le Riche and the male ensemble in Bolero

Nicolas Le Riche and the male ensemble in Bolero

Photo: Stephanie Berger

My guest for the opening night program, with which Bolero concluded—with a bang, you might say–condemned the piece, which she was seeing for the first time, as incredibly vulgar. I was bored by the trite choreography, but deeply impressed by the sensuous power and selfless dedication to the enterprise of the two dancers I saw in the leading role. It was definitely a case in which maturity counted. The audience as a whole went crazy for it. Standing ovation and all that. Yelps of delight.

The POB’s mixed repertory program will be followed by Giselle, created for the company in 1841. I can’t wait.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias