American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / through July 7, 2012

We are in India, a long and mythical time ago. A Brahmin priest lusts after Nikiya, the loveliest of the temple dancers, a situation acceptable neither to his gods nor to the young woman. She loves the warrior Solor, who returns her feelings. Solor, however, has been promised to the rajah’s daughter, Gamzatti, who, in desperation (or an access of evil), finishes off her rival with a poisonous viper embedded in a basket of flowers. Nikiya has a busy time of it in her afterlife—beginning with the sublime Kingdom of the Shades scene and ending in cataclysm, after which she and her beloved are finally joined for keeps in a luminous apotheosis. American Ballet Theatre takes us on this tour with Natalia Makarova’s staging of Marius Petipa’s La Bayadère, a combination of colorful hokum and classicism at its purest.

In a single week ABT fielded no fewer than seven ballerinas in the role of Nikiya. Of those I saw, the one that ignited my imagination was Veronika Part. Shedding her long uncertainty about her technical capability, she has come into her own to the point that her rendition of the role extinguished my desire to see any other.

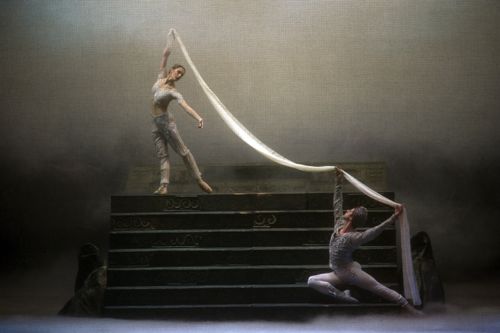

Veronika Part (as Nikiya) and Marcelo Gomes (as Solor) in Natalia Makarova’s production (after Petipa) of La Bayadère for American Ballet Theatre

Veronika Part (as Nikiya) and Marcelo Gomes (as Solor) in Natalia Makarova’s production (after Petipa) of La Bayadère for American Ballet Theatre

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Possessing extraordinary personal beauty in face and figure (tall, exquisitely proportioned, with just enough flesh to give her a voluptuous air), Part is, just physically, a perfect object of desire. Strangely enough, though, In the world of classical ballet, good looks don’t count all that much; dancing is unquestionably the key factor. Galina Ulanova, among the greatest of the 20th century’s ballerinas, was plain-faced and stocky, but the eloquence of her dancing—which I saw only at the end of her career and then only briefly—remains one of my touchstones.

At least half of the ravishing dancing Part did in Bayadère was predictable. For some time now audiences have reveled in her softness and liquidity. Her Nikiya seems to be dancing on plush and moving, as people once said of Margot Fonteyn, like honey poured from a jar. Her line has always been magnificent—an ever-shifting picture of grace, harmony, and royal breeding—but only now does she display it with full confidence, giving her audience example after example of what classical dance (that strange, exacting art) makes possible. What’s more, nothing she does looks forced; she doesn’t appear to be making any effort at all. (Needless to say, this is an illusion.)

Other elements in Part’s evolution—the strength, the control, the precision—are probably the last thing her admirers expected. In the past, although she offered her fans enough for them to consider her unique and wonderful, she’d hold back in her attack on a step, a phrase, a balance, or a lift, apparently through anxiety about her ability to execute it securely. Her hesitation was frequently so evident that her spectators grew nervous too. Now she trusts herself more and the audience can trust her in turn.

Part and Gomes in La Bayadère

Part and Gomes in La Bayadère

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Part’s interpretation of Nikiya has a distinct through-line logic. Her Nikiya personifies the powerful innocence of a child; she’s a creature who knows exactly what she wants (Solor, forever). Single-minded, she pursues her goal, dangerously loath to recognize evil—shocked time and again by its manifestations—or even opposition. Confronting Gamzatti to insist upon her claim to Solor, she’s completely unaware of the conniving familiar to the world of wealth and power.

At the same time she’s impulsive—ready, literally, to plunge a dagger into Gamzatti if her rival insists on co-opting the man she loves. When the priest offers her an antidote to the viper’s poison (as I’ve suggested, the narrative of Bayadère requires utter suspension of disbelief), she sees Solor leaving the scene with Gamzatti and opts for death. Part’s Nikiya is also, tragically, incapable of realizing that people can be of two minds about an issue of utmost importance, Solor being the poster boy for that state.

Of course I doubt that Petipa was concerned about subtle motivations for his characters. It’s the people who subsequently staged Bayadère who tried to make the narrative acceptable for their own time, so that Petipa’s choreography, similarly adjusted, would be remain available.

Part and Gomes in the apotheosis of La Bayadère

Part and Gomes in the apotheosis of La Bayadère

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Part was matched with the Solor perfect for her—Marcelo Gomes, who is not merely an imposing dancer, but also an intuitively supportive partner; no ballerina could do better than to be in his care.

Gillian Murphy, who plays Nikiya on other occasions, here gave the role of Gamzatti a sympathetic psychological dimension. At first she’s the rajah’s daughter, assuming her entitlement to Solor. Then, in an affectingly developed solo, she realizes that her beauty, her regal status, and its accompanying stupendous wealth are not enough to possess him. Rightly, she doesn’t go so far as to realize the unpredictable, irrational (or at least inexplicable) nature of love, because that would make the ballet a tragedy when it was surely first conceived of as an entertainment—albeit an entertainment created by genius.

The quality of the dancing throughout the ranks was excellent; the female corps de ballet in the Kingdom of the Shades scene was superb. Throughout, from its reaction, the audience, ensconced in its red velvet chairs, seemed to know what was good enough, what was really good, and what was beyond belief wonderful. Without question Veronika Part’s dancing fell into that final, sparsely populated, category.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias