Paul Taylor Dance Company / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / March 5 – 24, 2013

Paul Taylor, having boxed in the stage of Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater so it won’t look outlandishly large for a modern-dance group—it was built, first and foremost, for the New York City Ballet—has added two new works to the repertory of his company, which is in residence through March 24. As usual when Taylor comes on stage at the end of the program to take a slightly abashed bow—he has never forgotten the boy he once was—his gala clothes seem to fit his swimmer’s body with a slight awkwardness and absurdity. In the era in which he was still dancing, he took his curtain calls in a ratty blue terrycloth bathrobe—a more Taylorish outfit, if you will. The present set-up was bound to look “faux” to old-time fans.

Still, Taylor has reigned for over half a century as one of the supreme choreographic talents of our era—think Aureole (1962); think Last Look (1985); think all the astonishing wonders before, after, and in between that bear witness to both the joys and horrors of the examined life and its extension into the imagination. I hesitate to be negative about a gift and an output that’s well-nigh unequaled in modern dance, even if this season’s newbies don’t figure among Taylor’s best achievements.

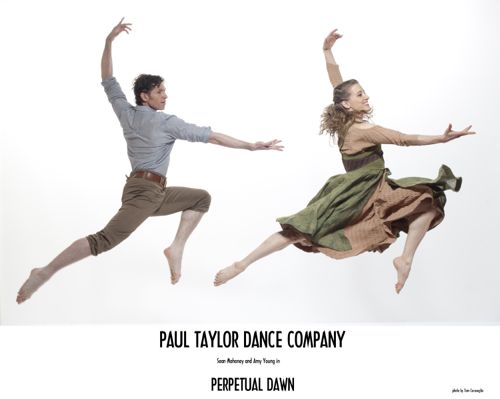

Dancers: Sean Mahoney and Amy Young Photo: Tom Caravaglia

The better by far of the two novelties is Perpetual Dawn, set to an easily forgettable score from Johann David Heinichen’s “Dresden Concerti.” The dance is a pretty thing mired in the greyish-pink sweetness of Santo Loquasto’s set, but not even the celebrated Jennifer Tipton’s lighting can lend it the necessary contrasts that might infuse the dance with vitality.

Loquasto’s set, as the ballet’s title suggests, is firmly committed to a palette of pink that is, granted, carefully not intolerably cloying, and a mousey gray-brown that makes you think of real velvet and its seductive texture. Trouble is, it’s just all too nice. One doesn’t—or shouldn’t—go to the theater for “nice.” “Nice” is for Hallmark cards. With these tones, the set vaguely delineates a peaceable outdoor landscape early in what promises to be a lovely day. Has Taylor conveniently forgotten that, more often than not, “pretty” is not a compliment in the art world? Loquasto’s complementary costumes, in the decoratively-inclined country-folk vein, are just what you’d expect and a telling example of why girls now often prefer jeans.

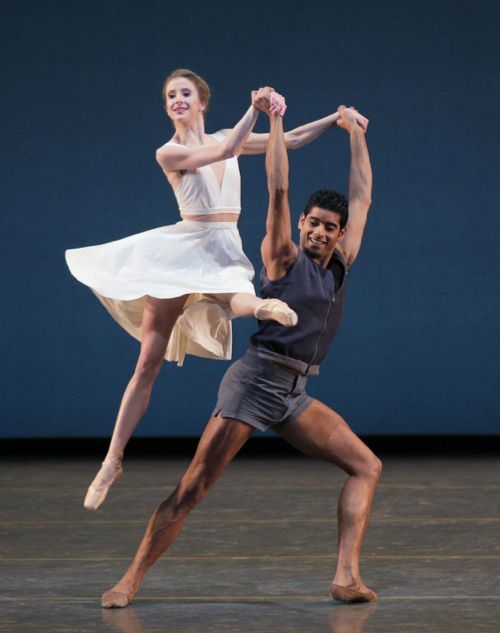

Expressing their pleasure in their surroundings with much pairing off, the 11 dancers of the piece couple up a lot, loyal as pigeons, it would seem, but the choreography is a clear set-up for the odd-man-out situation. In this case the character usually lacking a partner is played by a self-confident woman, Michelle Fleet, whose stardom has grown slowly and evenly during her years with the company, strewing much admiration along the way. I may be hypersensitive in bringing this up, but I was distracted by the fact that the character who was shunned—and understandably acting displeased with her situation—is the only black performer in the company.

The dancers display sheer joy in their dwelling place, but when the time of day slides into eventide, with its thoughtful or dreamy melancholy, the dance is finally given the contrast and variety it deserves (and needs).

Towards the end of the piece, Taylor’s lovers become especially playful with each other—a guy shepherds a gal through a slow cartwheel and the pair makes the move seem sexy, not circusy; it’s then that you finally feel you’ve had a meaningful peek at this choreographer’s multifaceted intelligence.

Dancers: Francisco Graciano, Robert Kleinendorst, and Sean Mahoney Photo: Tom Caravaglia

The second new work, To Make Crops Grow, starts out with some gourds and suchlike in the form of harvest items, and moves on to a version of a familiar myth, perhaps best known from Shirley Jackson’s short story The Lottery, which I recall from a classroom reading assignment in Middle School (back then, Junior High). Maybe Taylor read it there too, though I believe his formal education was sketchy. (Just as well.)

The gist of the mythic tale it is that a human member of a small, tight-knit community is sacrificed to make the group’s harvest fruitful; the victim is chosen by lottery with the common consent of all involved. Taylor’s version has some of the ominousness appropriate to such a venture, but, as far as I could see, no new take on a situation you’d assume was just up his alley. At one point there’s a loving duet for a pair who, it seemed to me, were worth their weight in gourds, and then some.

Most of the characters (some of them presented as youngsters, others as elders—that is, as part of a family)—seem to be into farming, though there’s at least one pair wearing more citified clothes. Customers at a roadside stand? At any rate—my grip on the goings- on got more and more slippery as the dance progressed. The farming folks are visited by some sort of cockamamie magician who, with doubtfully intentioned assistance (and, thanks to Loquasto, a complicated hat), indicates he’ll work wonders for the community’s harvest. Each person choses a folded slip of paper that (as these ‘lottery” tales go) indicates, when opened, whether its recipient will be chosen to be sacrificed so that the gourds et al. may be plentiful, delicious, even, ironically, life-giving—or spared .

Onstage, the whole business seemed rather tame and unclear, though the the situation called for excitement, fear, and hysteria in both individuals and small crowd clusters, and, in the end, a climactic attack. Perhaps a major choreographer should employ a knowledgeable dance watcher to whisper into his ear on the rare occasion it’s necessary, “No, dear, not this one.”

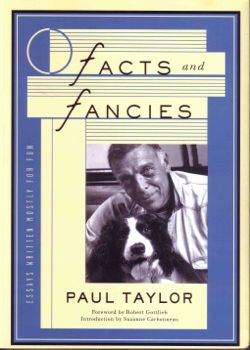

Meanwhile Taylor has published a new book of essays on dance, Facts and Fancies (Delphinium Books, $11.48 through Amazon). It’s nowhere near as important as his earlier memoir, Private Domain, and the degree of irony present in each of its pieces is exhaustingly varied. It does reprint from Private Domain Taylor’s wonderful essay on the making of Aureole, his first hit, which the choreographer finds less wonderful than do most of his public.

© 2013 Tobi Tobias