New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / September 17 – October 13, 2013

On September 19, with considerable fanfare in the media, the New York City Ballet gave its Fall gala. The orchestra was raised on a platform, liberated from the pit that is its usual home, to let the spectators ogle the musicians. The downstairs portion of the audience, many of them clearly one-percenters, was outfitted in expensive-date-night costume. Plenty to look at without a dancer yet in sight. Then the musicians charged the air with excitement, an enthusiastic rendering of John Adams’ Short Ride in a Fast Machine urging them on. Finally the dancing took over—the three major pieces on the program having their world premiere. Each was first introduced by a video that expanded upon Martins’ notion of allowing high-end designer fashion to play an important role in City Ballet’s proceedings and, by this means, to increase the company’s audience.

Up first was Justin Peck’s Capricious Maneuvers, set to music by Lucas Foss. The costuming is by Prabal Gurung (who, a program note wanted us to know, has clothed both Michelle Obama and the Duchess of Cambridge). The five dancers who share the stage space looked fresh and lively in a stern but striking palette of black, white, and red. There’s an onstage piano, around which the dancers gather when not in action–a move that is already a cliché.

New York City Ballet in Justin Peck’s Capricious Maneuvers

New York City Ballet in Justin Peck’s Capricious Maneuvers

Photo: Paul Kolnik

When they were fully animated, the performers looked like a cheery group of youngsters, a population typical of the disarmingly ingenuous types beloved by Jerome Robbins in his earlier and lighter ballets. If Peck had been given an explicit assignment, it seemed to be the job of creating an inviting curtain raiser. Capricious Maneuvers fills that order well enough, but it hardly filled the role of striking the viewer as something he or she didn’t already know.

If Peck’s contribution was charged with gaiety, Benjamin Millepied, named as the boss-to-be of the Paris Opera Ballet, initiated a heavy mood of doom that paralyzed the spirit. Its title? Neverwhere. Its music? By Nico Muhly, a frequent Millepied collaborator. Its costumes? By Iris Van Herpen, who is prominent (and attractively modest) in the introductory videotape.

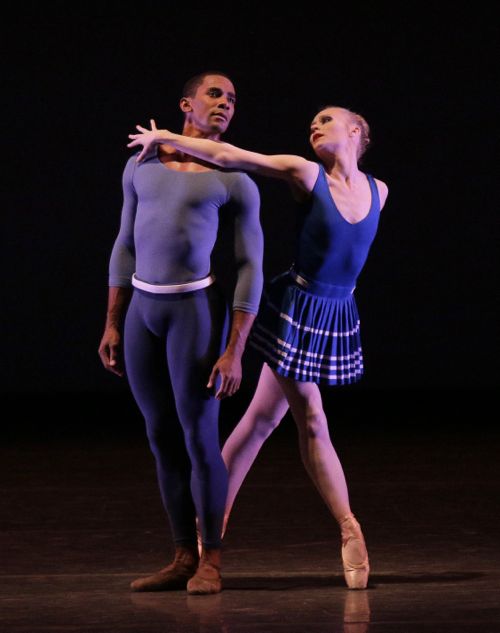

Sterling Hyltin and Tyler Angle in Benjamin Millepied’s Neverwhere

Sterling Hyltin and Tyler Angle in Benjamin Millepied’s Neverwhere

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Costume-wise, the big deal in this piece is the outré foot-gear. The six dancers in the ballet, three of each gender, wear practice garb in a fabric that looks like patent leather (but is light-years away, I can assure you, from kiddies’ Mary Janes). The women sport knee-high boots of a similar fabric. These ladies are also assigned short-skirted tutus that capture the light and have the appearance of dark (and, surely, evil) stars.

By the way, it’s just the women who wear the boots. The men are made to look barefoot in soft, flesh-colored ballet slippers. Surely there’s some amateur psychology lurking here, but I can’t bear to think of it, it’s so obviously faux-sophisticated. Or perhaps the foot-gear budget had gone way over its limit. The choreography is of negligible interest. And I suspect that the costuming is sheer eye candy—licorice perhaps.

It’s hard to know what the choreography may be trying to tell us—if anything. It seems to consist of brief, unrelated situations that have no affect at all. Here and there it simply yields one pretty position after another. Lots of the dancing takes place against a huge pyramid, which, as time goes by (oh so slowly), gets bathed in various colors of light. At one point a woman keeps testing the grip a man has on her—until he simply carries her away as if she were an unwieldy package he was destined to drop off at his next stop. At another point we see a duet disappearing, each of its dancers retreating to his or her corner, so to speak. But the choreography is largely devoid of instances of simple human connection. Who knows? Maybe the Parisians, who use aloofness as their default manner, will think it’s le dernier cri.

Tiler Peck and Robert Fairchild in Angelin Preljocaj’s Spectral Evidence

Tiler Peck and Robert Fairchild in Angelin Preljocaj’s Spectral Evidence

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Last of the new works was Spectral Evidence by Angelin Preljocaj, set to music by John Cage and costumed by Olivier Theyskens. If you worked hard at making the choreography “mean” something, you might have decided it was a gloss on the witchcraft hysteria that riddled Salem at the close of the seventeenth century. Theyskens offered muted clues: the men tightly clad in uniform forbidding black suits, while the women were wrapped in flowing pearly white, ornamented with red streaks that looked much like rivulets of blood. I couldn’t help wondering why Preljocaj chose to ignore the teachings Balanchine set forth again and again a good while ago, confidently demonstrating, through the example of his own ballets, the differences among the nature of literal narrative, suggestions of narrative, and absence of narrative, all of which he handled with aplomb.

At any rate, Spectral Evidence remained uncertain—and ineffectual—whether considered as a near-abstract ballet or one that referenced a specific historical event in America’s culture. Its confusion and its refusal to make any point decisively only added to the sense of hopelessness that grew more leaden until the audience was revived with a bit of Balanchine’s upbeat Western Symphony, then mercifully allowed to go home. I hope the watchers in the dark this evening remember the authority and elegance of the company’s dancers, despite the choreography they had no choice but to illuminate as best they could.

Balanchine’s Western Symphony, performed in October, 2010

Balanchine’s Western Symphony, performed in October, 2010

Photo: Paul Kolnik

As for the decision to overemphasize the importance of “what the dancers wore,” I feel this is a good moment to point out it was at Balanchine’s wish that in the house program the credits for each ballet the company danced at a given performance were listed with the creator of the music first; the choreographer’s name came second. The new ballets unveiled at the gala program—in deed if not in word—put its money on the clothes. We should remember, too, that for some of the most significant Balanchine ballets—The Four Temperaments being one example—the costumes found their final form by being “reduced” to the simplest of practice clothes.

© 2013 Tobi Tobias