American Ballet Theatre: Gala / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / May 14, 2012

The 15 items presented in American Ballet Theatre’s gala opening night program proceeded, one after another, like items on a To Do list. The individual numbers, most of them familiar (at least half of them overfamiliar), provided many an occasion for multiple fouettés for the ladies, kamikaze feats both old and startlingly new for the gentlemen, and crises of passion for the couples. The show fulfilled its ostensible purpose of presenting every principal dancer on the roster—and many of the soloists. As a whole, though, it was exhausting to the eye and the spirit.

Considered individually, of course, almost every entry contained something very fine or at least instructive to notice. Here’s what I noticed:

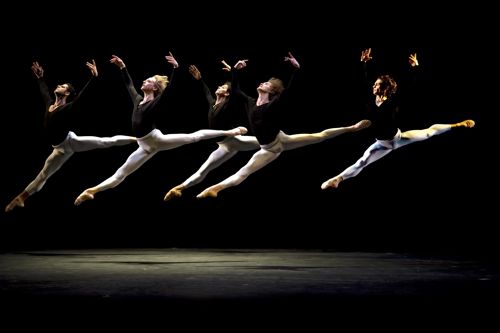

American Ballet Theatre dancers in Christopher Wheeldon’s Thirteen Diversions

American Ballet Theatre dancers in Christopher Wheeldon’s Thirteen Diversions

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Sections of Christopher Wheeldon’s Thirteen Diversions (music: Britten) opened and closed the program. Every dancer participating seemed as swift and sleek as a human being could be. However, the choreography—to my mind, some of Wheeldon’s best—suffered mightily from being broken up.

Strangely excerpted from Le Corsaire (Anna-Marie Holmes, after Petipa and Sergeyev; music: Adam), three Odalisques revealed clear individual temperaments. Sarah Lane demonstrated the beauty of small things rendered with exactitude; Misty Copeland represented vitality; Isabella Boylston proved, once again, that clarity has a spiritual dimension.

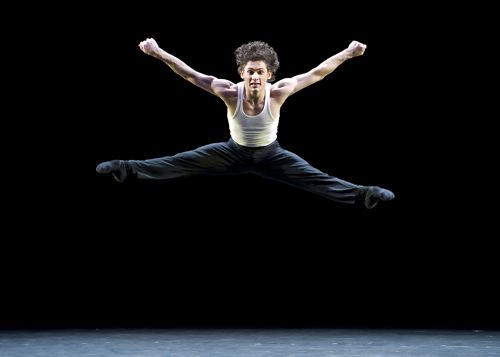

David Hallberg in La Bayadère

David Hallberg in La Bayadère

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Trailing clouds of glory, David Hallberg showed that his concurrent work as a member of the Bolshoi Ballet is the graduate schooling for his talents. In the Act II pas de deux from La Bayadère (Makarova, after Petipa; music: Minkus) with Polina Semionova, his dancing was clearly more spacious and forceful, with no loss of subtlety. Semionova is not the best partner for him, even though she does complement him in height; she’s too much of a strongwoman, while he projects dreams you can understand as if they were your own.

The program returned to Le Corsaire—a ballet clamoring to be excerpted—but Paloma Herrera and Cory Stearns failed to distinguish themselves in the “Bedroom” pas de deux. Without doubt, Herrera is technically superb, but her representation of feeling always looks painstakingly learned, not experienced. As for Stearns, he is perhaps not the guy you’d want to trust to let go of you mid-air.

Veronika Part is invariably fascinating to watch, but even she can’t transform Susan Jaffe’s Blue Pas de Deux (music: Alessandro Marcello) into a silk purse. Her partner was Thomas Forster, unprepossessing in the role, though not even Marcelo Gomes could have saved the day.

Gala programs frequently harbor a piece for a star in a guise other than the one he’s accustomed us to. The slot was filled this time by the acrobatic virtuoso Daniil Simkin proposing himself as a French low-life who hangs out in seedy cafés. Ben Van Cauwenbergh’s Les Bourgeois, set to a Jacques Brel song of that name, had Simkin clowning around, to be sure, but only in between executing never-before-seen feats.

Probably the most famous duet in classical ballet, the Act II pas de deux from Swan Lake (here, “after Ivanov”; music: Tchaikovsky) was danced by Irina Dvorovenko and Maxim Beloserkovsky. The two are poorly mated for double work in the traditional vein because (1) she overwhelms him physically and (2) their stage temperaments clash. She’s a Russian diva type; he’s essentially a Romantic dancer whose ideal Odette might be Alina Cojocaru.

Polonaise D’Enfants (music: Glazunov), choreographed by Raymond Lukens, a member of ABT’s education and training team, presented a selection of students ranging from grade schoolers through ABT’s junior troupe. The two littlest boys were irresistible; a medium-sized boy displayed a virtuoso’s ambitions; the young female teens were outranked by their School of American Ballet counterparts. The members of the junior company, who have not necessarily come up through the ABT school, have already jumped, unscathed, through flaming hoops.

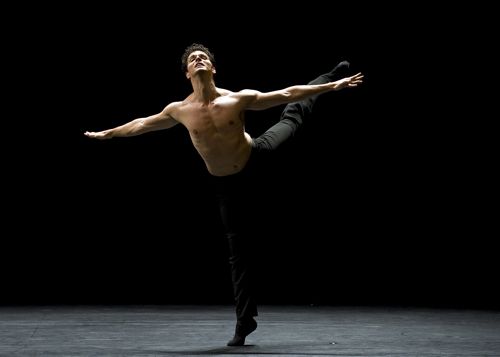

Marcelo Gomes and Diana Vishneva in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet

Marcelo Gomes and Diana Vishneva in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

In the Balcony pas de deux from Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet (music: Prokofiev), Diana Vishneva created a motivation for her every move. I loved the way she walked out onto her balcony and raised her arms to the sheltering night sky and her initially running away from her newly beloved like a moth terrified of being trapped. Her Romeo, Marcelo Gomes, was nowhere near as febrile as she but so adept as a partner that he seemed an organic part of her own dancing.

It was marvelous to see Herman Cornejo in fine fettle once again after a long recovery from injury and last season’s comeback performances. His partner, in the Act III pas de deux and coda from Don Quixote (after Petipa and Gorsky; music: Minkus), Xiomara Reyes, has nothing like his artistry, but she’s a spiffy technician. Fouettés—of which we saw far too many in the course of the evening, each set with its quirky variations—are child’s play to her.

Angel Corella and Alina Cojocaru in MacMillan’s Manon

Angel Corella and Alina Cojocaru in MacMillan’s Manon

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

In the Act I pas de deux of MacMillan’s Manon (music: Massenet), Alina Cojocaru, sympathetically partnered by Angel Corella, coupled the theme of sexual urgency with that of irresistible youthful sweetness. The dismal fate of these lovers was foreseen only by viewers familiar—as many balletomanes are—with the long, tangled tale.

Gillian Murphy and Vadim Muntagirov made an odd couple in the Act III pas de deux and coda of Swan Lake (after Petipa; music: Tchaikovsky), she playing an Odile only America could have bred (athletic, straightforward evil), while he was an Old World Siegfried (all elegant balletic manners, no rough urgency). He’s Russian born, trained in Perm and at the Royal Ballet. They might learn a lot from each other.

Ironically, in the Act I pas de deux from John Cranko’s Onegin (music: Tchaikovsky), Roberto Bolle, who hasn’t yet learned how to act, looked far too young and unsophisticated for the role, while Julie Kent, a veteran ballerina, was utterly convincing as an inexperienced young girl suddenly hurtling from virginal innocence to reckless passion. Cultivating acting as part of her skill set has lengthened Kent’s career by a decade.

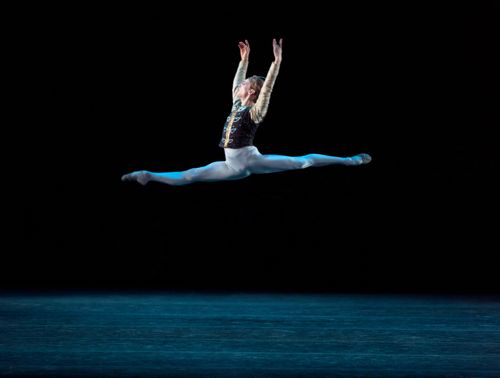

Natalia Osipova in Flames of Paris (after Vainonen)

Natalia Osipova in Flames of Paris (after Vainonen)

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev brought the gala performance to a rip-roaring close dancing the Flames of Paris pas de deux (after Vainonen; music: Asafiev)—a party-piece for super-adventurous virtuosi. She astonished with her ability to levitate. He was a wild man, eager to risk life and limb—he did even fall once—in order to be swifter, higher, more physically inventive than any danseur or stunt man in the movies. Fortunately he brought some mocking wit to the undertaking, which diminished its vulgarity.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias