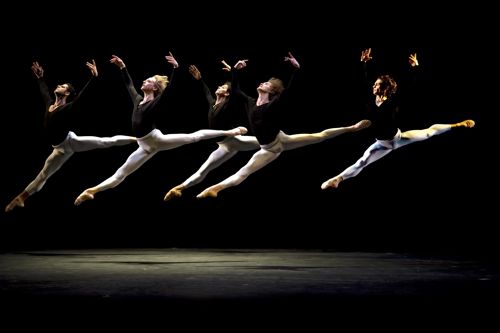

Kings of the Dance: Opus 3 / New York City Center / February 24-26, 2012

For the third time, Ardani Artists, an outfit specializing in the spectacular, brought us Kings of the Dance, a series of star turns contradicting Balanchine’s famous pronouncement that “ballet is woman.”

Photo: Gene Schiavone

This time the kings were—in alphabetical order, of course—Guillaume Côté (National Ballet of Canada), Marcelo Gomes (American Ballet Theatre), David Hallberg (ABT and Bolshoi Ballet), Denis Matvienko (Mariinsky Ballet), and Ivan Vasiliev (Mikhailovsky Ballet). Each in his way worthy of a crown.

The roster included no dancers from the New York City Ballet—or, for that matter, from the Paris Opera Ballet—though these are two of the world’s most aristocratic troupes. Are their dancers forbidden to undertake such assignments because the gig isn’t high-minded enough? For all their circusy atmosphere, the two previous kingly productions managed to include some high-quality material—Frederick Ashton’s soul-stirring Dance of the Blessed Spirits, for example—that rescued the show from hopeless vulgarity. Still I guess you could say the very premise of Kings is anti-art in its notion that ballet can be fairly represented by tours de force deprived of meaningful context and casting limited to a single gender.

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Regardless of its high-achieving dancers, Kings III is done in by its rep. The participating choreographers are, as a group, enough to make the heart sink: Mauro Bigonzetti, Edward Clug, Patrick de Bana, Jorma Elo, Marco Goecke, and Marcelo Gomes (the last renowned as a dancer but little known as a dance-maker). All of the ballets are new, apparently made for the Kings’ tour that, ending in New York, had visited venues as disparate as St. Petersburg and Orange County.

Strangely enough, most of these new pieces seem related, as if the choreographers had been handed a list of required moves at the studio door. The opening work, Bigonzetti’s Jazzy Five, has a sequence of angular, interleaving moves for the arms and hands that was maddeningly reiterated throughout the piece, which usurped the entire first half of the program. It then cropped up, like an insidious virus, throughout the rest of the evening. Even before I saw it infect a second body, I wanted to taser it. Jazzy Five presents its quintet of lavishly gifted men, experienced in their art, as a brotherhood of goofy adolescents clowning around in the locker room or at a sock hop. The material insults these dancers; worse yet, they can’t bring it off. BTW: None of the Kings is convincing in the jazz mode. These guys are experts in classical dancing. Did the Ardani folks not notice that? Is it not enough?

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Post-intermission, the program offered a protracted solo for each dancer. Each of the men trained in the Russian tradition was touching in his devotion to the mood in which his character wallowed, even though, to an American viewer, he might have seemed melodramatic. In Clug’s Guilty, Matvienko appeared to be not so much haunted by his misdeed (think Dostoyevsky) as already tried, convicted, and imprisoned by ruthless powers-that-be—a scenario associated with Russia from tsarist times to right now.

Vasiliev was even more vivid in de Bana’s (titled as if by Graham) Labyrinth of Solitude. His evocation of chronic melancholia was completely persuasive. Unfortunately this achievement was undercut by the flaw plaguing the entire program: the dancer’s own best steps were inserted into the choreography like lardons into a roast. Vasiliev’s specialties are airborne and fantastic; they don’t do much to convey clinical depression.

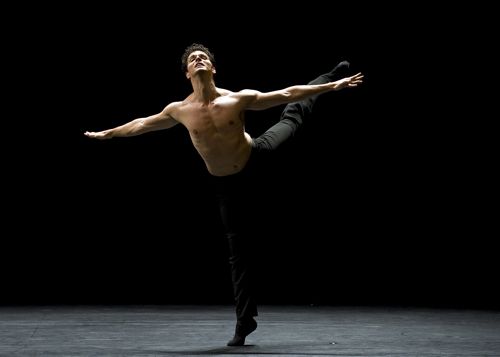

David Hallberg, with his immaculate dancing, lithe figure, and personal beauty, was criminally ill-served by Nacho Duato’s Kaburias. His costume, drastically flared and fringed ankle-length black culottes that he had to manipulate—flinging the fabric over his head, grasping a swath of it with his mouth—made him look inept and foolish. I guess that the choreographer hoped to kindle some sort of gutsy passion via this material, but Hallberg, a strikingly pale blond who is an icon of purity, just isn’t a likely conduit for earthly concerns.

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Côté, who combines precise technique with an unexpected flowing quality, gave as good a rendition as was possible of Goecke’s Tue under absurdly limited circumstances. The piece consisted mainly of vibrations of the hands with a throbbing obbligato from the head. Goecke treated these body parts as if they were the chief sources of power and beauty in neo-classical dancing, as they are, arguably, in Indian dance. The curtain line of the piece had Côté executing a classical port de bras. Inevitably, once he hit this formal stance (en couronne, ironically), he sent it into reverberation mode.

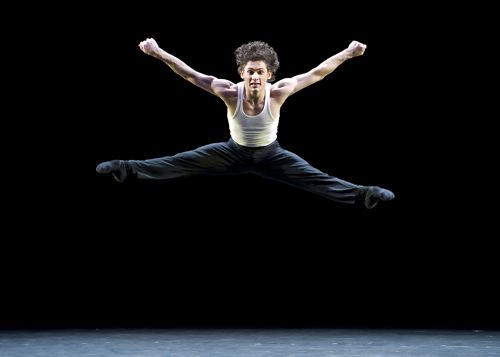

The absurdist play-on-words title of the solo assigned to Marcelo Gomes, Still of King, itself announced that the choreographer was the inexplicably popular Jorma Elo. It’s Elo who regularly claims his viewers’ attention by murdering language in that meaningless, pompous way. Then he moves on to offing la danse. He takes it as his mission to deconstruct the classical ballet vocabulary then walk away, leaving the jagged shards on the floor, but not before adding some lethal moves to the mess to give it the correctly bleak postmodern mood. Lately, he’s resorted to classical music as a foil; here he appropriates parts of a Haydn symphony. But the abettor aiding him most is Gomes himself.

Photo: Nikolay Krusser

Yes, the dancer starts out doing Elo’s familiar stutter-stop business, but, given his fleshy, muscular presence and his sexy good looks, there’s no way he’s going to look jittery or victimized doing the spastic routine. He remains fully in command of the situation despite the gyrations; he looks almost coherent, even relaxed. Best of all, he has a sense of humor. Where Elo’s choreographic ideas are patently ridiculous, Gomes makes them mildly funny, even fun, companionably sharing the joke with the audience. This was the only item on the Kings program that I’d be willing to see again.

KO’d, with an overwrought classical-style score by Côté and busy, busy choreography for all five of the Kings by Gomes, provided a finale of sorts. In theory this recognition of multiple talents in a single artist can only be seen as positive. Meanwhile, though, Gomes probably shouldn’t quit his day job.

Photo: Gene Schiavone

© 2012 Tobi Tobias