In Philippe Decoufle’s “Tricodex” a wheeled wooden frame creates a proscenium evoking stages of yore; in and around it old-fashioned feats of balance and flying seem to be caught in gaslight illuminating the dark. Village Voice 5/4/04

BALLET GALORE: WEEK #1

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 29, 2004

Following are some comments on the highlights of the opening week in the New York City Ballet’s spring season, Part II of the company’s Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration.

LA VALSE:

I come to Balanchine’s La Valse laden with memories.

Shortly after the ballet’s creation in 1951, I had the privilege of seeing Tanaquil LeClercq in the role of the doomed girl—a striking figure of innocence in the glamorous, corrupt society sweeping feverishly around her. Francisco Moncion was her apt foil, in the role of Death.

Of all the dancers I’ve known who were potent in stillness, Moncion still ranks first; his gravity and projection in this ballet as he gradually but inexorably laid claim to his prey had the effect of smooth, heavy stones dropped into a calm, deep pool.

LeClercq—unique in everything she did, with her intelligence and wit, her long-limbed angular elegance, her chiseled profile, and her inherent mystery—played the ballet’s strange heroine entirely without sentiment. She asked not that you pity her but that you allow your imagination to participate in her fate. If Death took her as his bride because she was young, untouched, lovely, she also went to meet him—with curiosity, even bravado. She accepted the shadowy cloak in which he wrapped her, the macabre accessories with which he adorned her—relishing the jet jewels and plunging her hand into the long inky gloves—not with a reluctance born of fear but first with puzzled equanimity, finally with a rapacious appetite.

In the present production, Rachel Rutherford and Robert Tewsley (as her devoted, baffled suitor, the role created on Nicholas Magallanes), do the originals justice. Both exude the sense of place that makes the ballet potent. And both dance with real dramatic impetus, as if, for them, the story is new and vivid. Rutherford, a lovely but placid dancer, doesn’t possess anything like LeClercq’s instinct for fantasy, but she conjures up a believable and telling persona. She made me think of an adolescent, touching in her folly, who costumes herself in chic depravity and goes out on the town to risk her life.

In the present production, Rachel Rutherford and Robert Tewsley (as her devoted, baffled suitor, the role created on Nicholas Magallanes), do the originals justice. Both exude the sense of place that makes the ballet potent. And both dance with real dramatic impetus, as if, for them, the story is new and vivid. Rutherford, a lovely but placid dancer, doesn’t possess anything like LeClercq’s instinct for fantasy, but she conjures up a believable and telling persona. She made me think of an adolescent, touching in her folly, who costumes herself in chic depravity and goes out on the town to risk her life.

The ensemble dancers perform handsomely enough, but, for the most part, don’t seem to know what the ballet’s about. Blame their inability to probe their material on their own (a failure common among today’s performers) or blame their coaches, as you prefer. But how can they not have heard the frantic, decadent atmosphere in the music? For the entire first half of the ballet, they seem to be enjoying themselves at a pleasant-enough ball.

And Jock Soto, I’m afraid, is all wrong as Death. He has the right physical presence for the role—solemn and striking—but he emotes too much, as self-consciously sinister as a stagy Dracula, and simply does too much, reaching out to seize the girl and rough her up, instead of luring her into his realm through his magnetic presence.

Karinska’s inspired designs for La Valse are, of course, less vulnerable to the changes time inevitably wreaks on the interpretation of choreography. One of the glories of this ballet is the ankle-brushing tutus for the soloist and ensemble women. Overskirts of pearl gray gauze veil layer upon layer of gorgeous yet somehow horrifying color—scarlet, vermilion, magenta, lavender, rose, and tangerine—each gown adhering to one of three different palettes. The hues flame and blend variously when the women whirl on pointe or unfurl their exquisite, powerful legs, as if night and death could never fully conceal the magnificent and terrible sunset preceding the end of the world.

SONATINE:

At the moment of its creation, Sonatine was disguised as a curtain-raiser, a bagatelle, a pièce d’occasion. The occasion was the New York City Ballet’s Ravel Festival of 1975. The year marked the centennial of the composer’s birth and, while Ravel hardly inspired Balanchine’s choreography as Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky did, festivals excited ticket buyers’ interest, and attention to the composer functioned as a tribute to France. (Three decades ago America was not fussing about the local name for pommes frites, but still looking to France as a model of sophistication in the realms of the intellect, the arts, and, of course, cuisine and high fashion.)

The ballet—a duet accompanied by an onstage pianist—proved to be worth keeping, though casting it once the original dancers had left the company has been a challenge. Balanchine made Sonatine for Violette Verdy, a French import, and the ballet was tightly connected to that distinctive dancer’s extraordinary musicality and her piercing intelligence. (Verdy was fittingly partnered by another French dancer, Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux.)

The choreography depicts a partnership that is the acme of civilization. It displays its dancers in a multitude of promenades and gracious bows—to each other, to an unspecified occasion. The delicacy of ornament so prominent in French art surfaces in its small, precise articulations and flourishes. Delving deeper, the piece explores the myriad ways in which two bodies can relate to each other, hands joined, and, equally, how they can relate in space when they separate. The dancers seem to enjoy a state of mutual delight—yet one that is social, not intimate or passionate. Part of their pleasure appears to lie in sharing a standard of exquisite comportment.

Oddly enough, though, the moment in Sonatine that remains unforgettable to me from its early showings is all fervid Romanticism, a vein that keeps surfacing in Balanchine’s work, one that we overlook as we concentrate on the miracles he accomplished in his neoclassical mode. The headier leitmotif proposes a man who is all ardent reverence—call him the Poet; call him Balanchine, if you dare—yearning for an unattainable woman. She is not merely the object of his desire (tangible) but also his inspiration (ineffable). Think of the exalted adoration the man expresses toward the woman who twice vanishes and returns in the final passage of Duo Concertant. Think of the numerous occasions on which Balanchine portrayed Suzanne Farrell as the muse who is the elusive object of the Poet’s worship. Now this is not the way Balanchine usually cast Verdy, whose Cartesian temperament, with its emphasis on clarity and objectivity, was neither a likely purveyor of sheer sensual allure nor a likely object of ecstatic imaginings. But in this little moment I recall from Sonatine, Verdy, for just a few seconds, became such a figure.

At intervals in the dance, the woman leaves her partner, and he, in turn, leaves her. The departures don’t seem to carry any emotional freight; they’re intrinsic to the structure of the piece, allowing for solo work to offset the duet material and offering the temporarily inactive performer a little breather. But when she goes off—I think it’s a third time—the man dances briefly alone, then suddenly crouches low, Werther-like (originally, in the concave shelter of the onstage grand piano, though the position has now been moved to center stage). His despairing attitude leads us to believe she’s gone forever. Then—lo and behold!—she returns. Cued by a shift in the music, he looks up, gazes toward the faraway corner diagonally opposite him, and there she is, just standing there, like a statue gleaming in early morning sunlight. No need for her arm to beckon or for her face to register emotion. Even in dance, there are moments when movement is superfluous. Her mere presence is his entire consolation—his reward, perhaps undeserved, surely unexpected, a stroke of Fate in one of her rare benevolent moods.

This season the company invited a pair of Paris Opera étoiles, Aurélie Dupont and Manuel Legris, to fill the Verdy and Bonnefoux roles, and they made an exquisite job of it. Their execution of the choreography was a tribute to their schooling: very pure, very powerful, very controlled—yet fleetingly inflected with all sorts of subtle shadings. More than the originators of their roles, they allowed their contact to grow increasingly rhapsodic. So much so that the ballet’s ending—they exit whirling on crisscrossing paths to opposite sides of the stage—frustrated expectation. Verdy’s demeanor, on the other hand, hinted from start to finish that Apart was inevitably lovers’ destination.

KYRA NICHOLS:

The New York City Ballet called its all-Balanchine opening night program “French Tribute,” the scores for Walpurgisnacht Ballet, Sonatine, La Valse, and Symphony in C being by Gounod, Ravel, Ravel again, and Bizet, respectively. I’ve always thought that the atmospheric Emeralds section (Fauré) of Jewels was the most deeply French of Balanchine’s ballets, but never mind, the program offered a great deal of loveliness, which, for me, reached its pinnacle with Kyra Nichols’s dancing in Walpurgisnacht.

For the last several years, Nichols has quietly and steadily demonstrated how a ballerina can comport herself with continuing grace and growing luminosity as she nears the close of her performing career. Though time inevitably eroded her phenomenal technical capability, she has never relinquished the key elements—call them principles—of her dancing: the purity, the musicality, the self-presentation so modest, so tactful, so reticent that her dancing figure, offering almost no ego, looks simply like a flowering of the music or perhaps the incarnation of Balanchine’s imagination.

Many of Nichols’s former great roles are now beyond her, but in Walpurgisnacht she was perfect, spinning her silken web, phrase after phrase exquisitely modulated, the material inflected here and there, just fleetingly, with a hint of emotion, but not one you could ever put a name to. Nothing seemed calculated or forced; she moved, despite the intricate artifice classical dancing involves, with the radiance and joy of an ingenuous child. At the ballet’s last moment, when her partner displayed her in profile, perched high on his shoulder, her unbound hair streaming down her back, she looked like a figure on a ship’s prow, guiding her vessel out into uncharted territory, confident that she would encounter fair weather.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: (1) Rachel Rutherford and Robert Tewsley in George Balanchine’s La Valse; (2) Kyra Nichols in Balanchine’s Walpurgisnacht Ballet

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Sharing the Honors

Balanchine, Graham, Ailey, and De Mille appear, separated by perforation lines of course, on the United States Postal Service’s new 37-cent commemorative–American Choreographers. Issue date: May 4, 2004. Village Voice 4/28/04

TEMPTING FATE

Martha Graham Dance Company / City Center, NYC / April 14-25, 2004

If a long winter—meteorological or psychological—has scuttled your courage, you might want to check out a couple of terrific Martha Graham dances now being performed in repertory at the City Center. Cave of the Heart and Hérodiade are part of the Greek cycle that Graham created in the 1940s, spurred by the period’s newly awakened appetite for a psychoanalytical view of classical mythology. Both pieces present a pair of women, each tremendously strong in her own way, who oppose and complement each other. One is clearly the star of the show, the other secondary but essential. (It’s pertinent that both characters are female. Graham was certain her gender ran the world; men were necessary, of course, but auxiliary.) Respectively, the juxtaposed women represent the impassioned renegade and the voice of reason that attempts to dissuade that reckless iconoclast from her dire purpose.

In Cave of the Heart, revived this season, Medea, her ferocious jealousy ignited when her husband, Jason, transfers his affections to an ingenuous young princess, devises a hideous death for her rival and murders her own—and Jason’s—two young sons. (Though the latter deed is not actually shown, Graham could assume her audience knew these stories.) The Chorus, in the form of a single stately woman, tries at length to deflect her from what she has resolved to do. And fails. Not for lack of trying. Not because the Chorus is wrong; it’s not; it has reason—and all of civilization—on its side. The Chorus fails because there is no stopping the raging spirits Graham embodied. The whole point of them is that they’re beyond reason, incapable of being contained. If a little self-immolation is involved, a female hero of this ilk says to herself, so be it. She is, in Graham’s words, “doom-eager.” Graham probably knew, too, if only in her secret heart, that wreaking disaster is a form of self-expression.

Hérodiade reduces the nature of the two women and their relationship to its essence. The pair constitutes the cast in its entirety, and ties to the St. John the Baptist narrative are all but abandoned. The Hérodiade figure is simply a daring soul in crisis, examining herself—laying her bones bare, as the set’s anatomical “mirror” sculpture suggests—and deciding to commit herself to a fateful action. The other woman fills the role of confidante and counselor, servant and protector. She personifies the wisdom of the world on how one may live placidly, which is all most people ask of their existence. Don’t embark on that path, she seems to be saying. Think of the consequences. The Hérodiade figure, of course, stands for the life lived fully, in defiance of good sense, in accordance with one’s deepest impulses. Hérodiade falters—Graham deepens the character as well as the drama by showing us that—then repossesses her resolve and goes to her destiny, radical and intrepid. Talk about role models!

Hérodiade reduces the nature of the two women and their relationship to its essence. The pair constitutes the cast in its entirety, and ties to the St. John the Baptist narrative are all but abandoned. The Hérodiade figure is simply a daring soul in crisis, examining herself—laying her bones bare, as the set’s anatomical “mirror” sculpture suggests—and deciding to commit herself to a fateful action. The other woman fills the role of confidante and counselor, servant and protector. She personifies the wisdom of the world on how one may live placidly, which is all most people ask of their existence. Don’t embark on that path, she seems to be saying. Think of the consequences. The Hérodiade figure, of course, stands for the life lived fully, in defiance of good sense, in accordance with one’s deepest impulses. Hérodiade falters—Graham deepens the character as well as the drama by showing us that—then repossesses her resolve and goes to her destiny, radical and intrepid. Talk about role models!

Having created such female heroes for herself—not only on her own idiosyncratic body, in a vocabulary she invented for the purpose, but also from her own ecstatic mindset—Graham inevitably set up a succession problem. What dancer was dynamic enough to inherit these parts and inhabit them as they deserved? A glorious few live in the memory of veteran fans. Today’s answer to the question is Fang-Yi Sheu, who, this season, is reanimating the title role in Hérodiade.

Born and initially trained in Taiwan, Sheu is a small, delicately boned woman with powerhouse strength and laser beam concentration. Her face has the theatrical impact of a Noh mask. In all of this she resembles Graham. One hardly knows what to marvel at first—the sheer technical command (her ability, for instance, to spring from one shape to another without any visible transition), the psychic capacity that enables her to maintain intensity even in stillness, or the dramatic power, which draws the viewer inexorably into the world of her imagination and holds him there, riveted, until at the end of the dance she lets him go, shaken and quite possibly changed forever.

Wisely, the company confined the repertory chosen for the current season almost exclusively to the great works of Graham’s early and middle periods. This strategy ensured that nearly all the sets on view would be the stunning sculptural inventions of Isamu Noguchi—an added advantage. Nevertheless, management decided to revive Circe, a later and lesser affair—perhaps to show off the bodies beautiful of the men it now has on hand. Ulysses, who sails into the realm of the evil enchantress (ironically in a Noguchi set recycled from an earlier, failed, dance), was played by Kenneth Topping as a straight arrow, while his Helmsman (David Zurak) appeared uncomfortably undecided as to his own erotic inclinations. But the crew, already transformed by the lethal lady, when we encounter them, into Snake, Lion, Deer, and Goat—well, my dear . . .

The Graham legend, a mythology in its own right, contends that she combined the Puritan and the sensualist in her makeup; ostensibly this made her an authority of sorts on forbidden games. Today, forty years after the premiere of Circe, its would-be sexy parts seem dopey to the point of embarrassment. The hero’s choosing to couple up with the ostensibly seductive witch bitch (a gimcrack figure in a gold maillot and firehouse-red cape) appears downright illogical; surely the extended soft porn shenanigans are setting him up for a frolic with the Helmsman. Snake, Lion, Deer, and Goat (Martin Lofsnes, Whitney Hunter, Christophe Jeannot, and Maurizio Nardi, respectively, the night I went), clad only in bikini trunks and face paint, were indeed ravishing to ogle. I’m happy to report that they danced with a grave beauty their circumstances hardly encouraged.

A third revival, The Owl and the Pussycat, proved, for any newcomer to Graham’s domain, that the choreographer had no gift for entertainment in the blithe gaiety mode. She could be mordantly witty—as in Acrobats of God, where she played herself, only slightly exaggerated, in the role of a driving ringmaster who has brought the cult of her own personality to the same fever pitch as her dancers’ skills. But the lightweight and the lighthearted lay beyond her.

Like Maple Leaf Rag, also included in this season’s repertory, presumably to leaven the dark psychological turbulence of Graham’s finest works, O&P was resurrected with André Leon Talley—Mr. High Style—speaking the familiar Edward Lear verse that the choreography illustrates with suffocating whimsy. A gentleman of impressive height, bulk, and panache, in still more impressive clothes (tweeds, cape, spats—contrived by Ralph Lauren), he was a sight to see, as were some charming moves the choreographer contrived for a trio of mermaids. (Unmentioned by Lear, these delectable, bipedally challenged creatures are viewed by the dance’s protagonists from their “beautiful pea-green boat,” contrived, in Noguchi-lite mode, by Ming Cho Lee.) Still, this is not the sort of concoction you want to encounter more than once in a decade. As for Maple Leaf Rag, I went home before its forced good cheer could be foisted upon me.

Photo credit: Arnold Eagle: Martha Graham (left) and May O’Donnell in Graham’s Hérodiade. Set by Isamu Noguchi.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

BAFFLED IN NEW YORK

North Carolina Dance Theatre / Joyce Theater, NYC / April 13-18, 2004

“It’s a puzzlement,” says the monarch in The King and I. Having witnessed one of North Carolina Dance Theatre’s rare New York performances, I can only agree with the king. The company is led by a pair of former New York City Ballet principals, Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux and Patricia McBride—the latter one of the great dancers of the twentieth century, the originator and/or brilliant interpreter of many a Balanchine role. Why, I wonder, did this energetic and engaging troupe ignore this heritage and offer a program comprising three pieces of middling worth only obliquely related to classical dancing?

My plaintive why is only intensified by the fact that NCDT’s repertory features a goodly number of Balanchine’s major works—all of them staged by McBride. The programming for New York is baffling—and frustrating. Even more so since, in the same week, Edward Villella—another star for the history books and frequently McBride’s partner at NYCB—is bringing his Miami City Ballet, consistently praised for the vitality of its Balanchine productions, within commuting distance of inner New York and essentially keeping the visit a secret. (Friday evening, April 16, at the Tilles Center on Long Island, MCB will offer the Rubies section of its excellent production of Jewels and two new additions to its sizeable Balanchine rep: Ballo della Regina, staged by Merrill Ashley, and Stravinsky Violin Concerto, staged by Maria Calegari and Bart Cook. Further information is available at www.tillescenter.com.) As far as I know, not a word of this appearance has been breathed to the dance press.

At any rate, there we were at the Joyce, watching NCDT in The River—vintage Alvin Ailey, to be sure, but hardly a piece that showcases classical prowess; Bonnefoux’s Shindig, a hoedown (set to welcome live music from the bluegrass band Greasy Beans) with sprightly footwork that fails to provide any adagio relief from its relentlessly brisk-‘n’-cheery allegro footwork; and Nicolo Fonte’s Brave! an all-too-generic modern-ballet deal featuring (1) an ominous atmosphere with intimations of violence; (2) sleek inky costumes that slowly—oh, so very slowly—give way to faux-nudity; (3) a plethora of high stools that get sat on and moved around; and (4) a cringe-inducing text (“I spoke my mind . . . I faced my fears . . . to love without prejudice”). Whose taste was the program geared to? The Joyce audience that supports annual four-week engagements of Pilobolus?

At any rate, there we were at the Joyce, watching NCDT in The River—vintage Alvin Ailey, to be sure, but hardly a piece that showcases classical prowess; Bonnefoux’s Shindig, a hoedown (set to welcome live music from the bluegrass band Greasy Beans) with sprightly footwork that fails to provide any adagio relief from its relentlessly brisk-‘n’-cheery allegro footwork; and Nicolo Fonte’s Brave! an all-too-generic modern-ballet deal featuring (1) an ominous atmosphere with intimations of violence; (2) sleek inky costumes that slowly—oh, so very slowly—give way to faux-nudity; (3) a plethora of high stools that get sat on and moved around; and (4) a cringe-inducing text (“I spoke my mind . . . I faced my fears . . . to love without prejudice”). Whose taste was the program geared to? The Joyce audience that supports annual four-week engagements of Pilobolus?

As so often, when choreography disappoints, the dancers cheer you up. NCDT’s are an engaging bunch. Uri Sands, a former Ailey stand-out, is the most gorgeous and sophisticated of them, with his eloquent upper body and a self-containment that seems to harbor deep emotional experience. He is the only one among them, at least in the offered repertory, who seems fully adult—and poetic.

Rebecca Carmazzi, captures some of the qualities that characterized McBride: the beautiful head that seems always to be turning to the light; the ability to be utterly clear, present in the space, wholly herself—without fuss or clamoring for attention. Nicholle-Rochelle, blessed with the build and looks of a Vegas showgirl, has the appetite and aplomb for pyrotechnical feats. Dynamos like this risk being coarse or mechanical; Nicholle-Rochelle is appealing because she seems to be having a good time.

Heather Ferranti-Ferguson, well matched with Sands in The River, is the loveliest of the women; she shares his calm and his suggestion of passions running deep. She’s a lyrical dancer essentially, but not one of those insubstantial, ineffable descendants of the Sylphide. Her movement is weighted, as if she’s been matching every ballet class she takes with one in modern dance.

The company harbors a slew of young men who might be undergrads at some mid-Western college—modest, still somewhat raw, their athletic inclinations lured off the beaten path into dancing. Their classical training seems to be right on target, urging them to be swift, crisp, immune to affectation. I wanted to see them again, so I could sort out which of them was which. And next time I hope to see them rising to the challenges and rewards of dancing Balanchine.

Photo credit: Marilyn Frenkel: Members of North Carolina Dance Theatre in Nicolo Fonte’s Brave!

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Ailey II; ABT Studio Company

They deliver physical wonders with a modesty so profound, it looks like our era’s most endangered commodity—innocence. (Ailey) Their rendering of Ashton’s sublime matched trios, Monotones I and II, which aimed, rightly, for immaculate classicism and calm repose, was infinitely poignant. (ABT) Village Voice 4/13/04

LIVING DANGEROUSLY

Compagnie Maguy Marin / Joyce Theater, NYC / April 6-11, 2004

A curtain of flexible strips in carnival colors screens the three walls of the stage like a vertical Venetian blind. Nine dancers—first one, then several—emerge from behind this pliant barrier, then, just as mysteriously, vanish back into the corridors it shields. Suddenly revealed, then quickly concealed, again and again, they’re figures in events without warning that occur in a territory in flux. Strong, swift, no-nonsense types (trained for the dance and dressed for the street, their faces registering nothing), they will spend 65 minutes uninflected by tale or temperament conveying the secret life of the hunted and haunted. The enigmatic name of the work is Les applaudissements ne se mangent pas (You Can’t Live on Applause). As its choreographer, Maguy Marin, indicates in her thankfully more pertinent program note, the piece springs from the horrific political and social conditions prevalent in Latin America, though the entire world, wherever power is wielded inhumanely, is implicated.

Some dancers enter by falling through the curtain, as if felled by sudden gunfire, DOAs. The others absorb the assassinations as if they were business as usual: glance down briefly, then immediately, automatically, turn away and go about their everyday affairs in which flight is prominent. The stricken bodies lie felled for a beat or two, then resurrect. One of the horrors of living in a state of siege, Marin implies, is that the events in it are infinitely recurrent.

Face to face encounters are often blank-faced confrontations. This is a society, if you can call it that, dominated by fear and the hostility that arises from chronic fear; the responses of one person to another are blunted or absent altogether. Unless they escalate to actual combat—most of it for couples, sometimes for several small groups. Without appetite or evident feeling—these people are beyond rage, emotionally anesthetized—they clamber up each other’s bodies to gain lookout posts, push one another down with a shove to the shoulder, then insult the abused body further, pushing it, kicking it, flinging it away like an unwieldy piece of trash. The roles of victim and perpetrator are interchangeable, of course. And the antagonism appears simultaneously political and personal. It infuses the climate. You can imagine the figures on stage, were they given to words, saying simply, “It’s the way we live now.”

Violence is interspersed with wary waiting. Even moments of stillness are charged with alarm.

Everywhere, people eye one another with ingrained suspicion. Trust, if indeed it ever existed, is absent from this terrain. Like spies, figures conceal themselves behind the curtain, then peek out—often, tellingly, to scan a temporarily depopulated stage space—or stealthily peer into the murky zone the curtain veils. As soon as one, looking in, proceeds to investigate what he’s glimpsed or imagined, another emerges from hiding to start a new probe. Later, one woman is left alone, abandoned by her companions who, moments later, appear to spy on her from a distance through chinks in the curtain. Elsewhere the population gathers to listen to furtively whispered secrets conveyed by a partner in an alliance that has a six-second life.

Yes, there is, fleetingly, some tenderness—a few embraces, but very few. Among the innumerable friend-or-foe? encounters, one, between two men, ends in a solemn hug. It’s motionless, just a pose, and so rare in the context that it startles. Are these the last people on earth who can remember love? Another, longer, embrace follows the most ominous group mêlée. The pair might be crying “Oh, my God, it’s you!” after some unspecific mass catastrophe had all but obliterated the hope of finding one’s significant other whole in the welter of the dead, the dying, and the debris. Even this relief lasts only a few seconds, though; the prevailing circumstances don’t allow a sense of safety to endure.

The most telling sequence in Les applaudissements goes like this: A woman falls. Another walks past her, looks down at her, then walks off. Cross-stage, three other figures, almost invisible behind the curtain, peer at the fallen body from between the slats, then go back into hiding. Seemingly close to death but not quite extinguished, the fallen woman—with the slow, fitful movements of the grievously ill or wounded—starts rolling to the opposite side of the stage as if some succor or at least shelter might lie there. Then, one after another, all the other bodies in the piece appear, recumbent like the first woman’s—feet pointing upstage, heads downstage—to roll after hers on the long horizontal path to the presumed safe haven. They make a terrible sound as they pick up speed, flesh impacting floorboard. Near corpses though they seem to be, they hurtle faster and faster, until all of them disappear to the far side of the stage—except for the last one, who doesn’t make it. A friend emerges to claim the doomed man, hold him as his life ebbs away, and remove him—to more hallowed ground, from the look of it, if, by chance, any should exist. At some point, as these events unfurl, we realize we’ve seen each element before.

Throughout the piece, the light glares and fades by turns. In the final minutes, the stage is steeped in a twilight so deep you can barely see what’s happening, yet from what you glimpse, you know. Much of it has occurred before, fully exposed. Ominous though it is, the growing darkness is merciful. By the time piece ends, you can barely make out what’s going on, but, pointedly, neither the spectators nor the figures that populate this nightmarish world are granted the mercy of a blackout. What’s going on here, Marin insists, keeps on going on.

Les applaudissements ne se mangent pas is handsomely done—with little air of contrivance. Using movement that’s rooted in a pedestrian’s vocabulary, Marin opts for the purity of the vernacular and bonds her viewers to her dancers. She manages the configurations of her stage picture as well as the continually shifting pulse of the action with an acumen a dance devotee can’t fail to admire. Even so, the piece may be difficult for the ordinary viewer to watch, let alone appreciate. Its duration—over an hour without a break—is a hurdle. And its refusal to succumb to the theatrical allurements of narrative, character, and structural patterns that offer obvious climaxes opens the door wide to monotony.

In the end, I suppose, the success of the work rests with its ability to kindle an emotional response in its audience—recognition of the universe it depicts, empathy with its inhabitants, identification with both, even incitement to leave the theater fired up to make the world at hand more pacific and just. In her own program notes, Marin describes Les applausdissements as polemical. Admirable though it is—it’s one of the most intelligent contemporary dances I’ve seen in some time—I don’t think it fully accomplishes what I take to be its humanistic goal.

Photo credit: Bruce Feeley: Members of Compagnie Maguy Marin in Marin’s Les applaudissements ne se mangent pas

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Maureen Fleming

When she swathes her nude body in miles of gauze animated by a wind machine and lit to look like fire, you cave right in to her theatrical know-how. Village Voice 4/5/04

TOYS R’NT US

Stephen Petronio Company / Joyce Theater, NYC / March 23-28, 2004

The press release for Stephen Petronio’s latest creation, The Island of Misfit Toys, being given its first New York showings at the Joyce, promised “themes that include obsession, guilt, insatiable desire and the mundane details of life.” The night I went, the crowd seemed wary—baffled perhaps—and gave it a lukewarm reception. C’mon, what’s not to like?

The press release for Stephen Petronio’s latest creation, The Island of Misfit Toys, being given its first New York showings at the Joyce, promised “themes that include obsession, guilt, insatiable desire and the mundane details of life.” The night I went, the crowd seemed wary—baffled perhaps—and gave it a lukewarm reception. C’mon, what’s not to like?

For some eloquent London critics writing at its premiere last year, the piece epitomized the downtown New York Zeitgeist—all glamorized dysfunction, decadence, and desperation. As with the solo Broken Man and City of Twist, two works from 2002 that shared the Joyce program (called “The Gotham Suite”), Toys proves Petronio to be a canny practitioner of a genre I’ve come to think of as KinkyChic. And, as is his wont, the choreographer has enlisted big names to bolster the edgy quality he lays claim to. The score is drawn from Lou Reed numbers; the set comes from Cindy Sherman; the costumes, from Imitation of Christ’s Tara Subkoff.

What’s not to like? Well, I have two complaints, both of them serious. One: Petronio substitutes fashion (not just clothes, but lifestyle, to use a relevant trash word) for meaning and feeling. Two: The dancing he devises—while executed with stunning fluidity, speed, and strength—is extremely limited in vocabulary, rhythmic interest, and structure. Not surprisingly, Toys is most telling in occasional images that would make reasonably potent shots in a latter-day glossy.

Sherman sets the scene with a pair of grotesque doll-like sculptures that loll on the apron of the stage, one huge-bellied with extra limbs and two pin-heads, the other with a gigantic head that sports a gaping hole where the face should be. Later she projects a totem pole of baby faces onto the backdrop. Each is rendered as a plump infant-Buddha mask, its impassivity distorted by fear, delight, rage, or grief. The visages evoke horror because, contrary to popular wishful thinking about the sweetness and innocence of the very young, people six months old really look like this as they experience primal emotions with unalloyed force. This photographic collage struck me as being the single genuine element in the show.

As the piece opens, Petronio—head shaved, sleek body outfitted in menacingly weird evening dress—lolls in a chair, back to the audience, smoking as he scrutinizes a bunch of figures with unreliable spines. He might be a PoMo Diaghilev auditioning prospects for his company. But, as if in a wannabe reference to E.T.A. Hoffmann’s riveting tales of the subhuman, the hapless dolls—creations, perhaps, of the Petronio character’s own imagination and ingenuity—come to half-life and wrest away his power.

The balance of the piece chronicles the gradual disintegration of the dolls—pajama-clad bodies inclined to mildly depraved sexual practices and an increasing impairment of their sense of center. As their physical coordination diminishes, they lose harmony, eloquence, purpose—in other words, the traits, based on connection, that define civilized beings. The dehumanization process goes on at a length that could only hold the attention of a voyeur, and I think Petronio casts his audience in that role. He doesn’t elicit empathy for, or even understanding of, the creatures in his garish, disjunctive parade; he offers the stuff up merely as titillating entertainment. Oddly enough, his inventions aren’t strong or singular enough to fill the bill.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

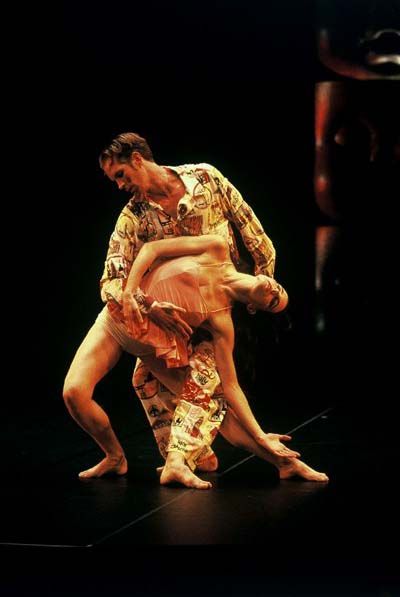

Photo credit: Angela Taylor: Gino Grenek and Jimena Paz in Stephen Petronio’s The Island of Misfit Toys

DARK VICTORY

Johannes Wieland / 92nd Street Y Harkness Dance Project at The Duke on 42nd Street, NYC / March 10-14, 2004

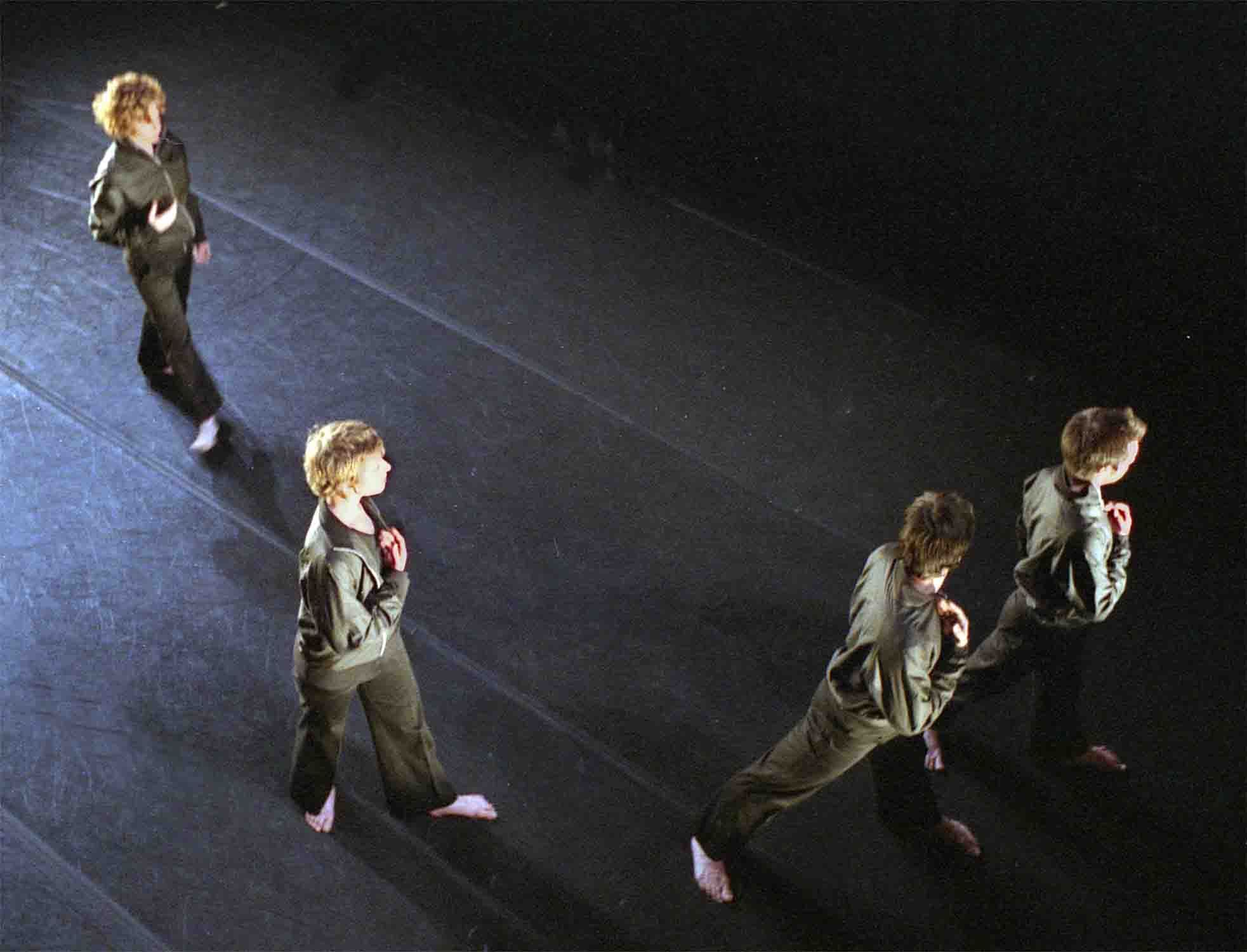

When Johannes Wieland operates in his signature style, he makes dances that are immaculately pared down and aggressive to the point of violence. Adamantly abstract on its surface, the work is haunted by subtle currents of emotion. His best achievement to date in this vein in the new Membrane, for eight black-clad dancers in a black-box void, only their faces, hands, and bare feet luminous as the moon in a midnight sky.

The figures are outfitted identically in jerseys, trousers, and windbreakers. Those chest-hugging zip jackets, though, are as much prop as costume. And they evolve, as the action develops, into a metaphoric skin—tough but capable of being shed or penetrated—that encloses and isolates the individual, cloaking his vulnerability to the effect of others, thwarting real connection.

The piece opens with a prologue of sorts. The man and woman who will prove to be the central couple (Julian Barnett and Eliza Littrell) maneuver each other into and out of their jackets, twisting and twining like a pair in a rubber-jointed circus act. Then the rest of the cast galvanizes into movement—sudden, powerful, and raw—that makes you think of gang warfare. Repeatedly, one dancer flings another’s weight around his body, finally positioning the partner high on his shoulders. The ploy suggests that their roles have abruptly reversed, slave becoming master, victim becoming terrorist.

The dancers group into duos, trios, quartets that reveal Wieland’s inventive command of structure. (He actually makes good on his press materials’ lofty declaration that he employs “an architecturally driven understanding of bodies, movement, and space.”) One trio, replicated by another in greater shadow, has dancer A supporting dancer B in a burly grasp so that B, predatory legs scrambling in the air, can tread up and down dancer C’s body as C stands riveted in place, stoically tolerating the repeated aggression. Then Wieland adds the two remaining cast members, who’ve stood immobile on the outskirts of the scene, like bystanders at a horrific event who can’t stop watching but do nothing to intervene or turn their backs, stonily refusing the role of brother’s keeper. And at this moment Wieland exercises his true gift. He gets you to quit admiring his organizational acumen and feel what a tough world these figures (indeed, all of us) inhabit, physically and psychologically. He has you walking right down those mean streets.

Eventually the dancers shed their windbreakers, and much is made of the stripping (usually at another’s hand) and of the garment stripped, which the owners continue to animate—viciously flinging it about, nuzzling it like a child with his “blankie”—even though they’re no longer wearing it. The shedding of the protective shell and the ensuing ridding the self of it—so that it’s not merely gone from the wearer’s back, but no longer in his possession–leads only to more violence, which builds to a frenzy. So much for the romance of attaining maturity.

In what you might call a coda, the dance refocuses on the main couple, now alone in the gloomy arena. Having, with the greatest difficulty and effort, laid themselves bare, they reap no reward. Instead, they’re consigned to continue their hard-won togetherness in a void of endless inconsequential repetition, treading in an amorphous space with no destination. It’s a suitable latter-day ending for a latter-day condition. Wieland neither sentimentalizes nor overdramatizes it. This calibrated reticence is a key aspect of his talent. He need only beware that it doesn’t stifle him.

Occasionally Wieland ventures into modes quite different from the one Membrane epitomizes. Another new piece, Filtrate, uses three distinct generations of dancers; eerily lit Plexiglas boxes that serve as cages for the participants; and an absurdist text involving a freezer, memory, and ice cubes. For the first third of its 27 minutes, while I was still making my best effort to scrutinize it, I found it inscrutable. After that, I found it affected and dull. But, though I would never willingly watch this piece again, I’m not railing at Wieland for making it. Like ordinary folks, choreographers have to explore paths that may lead them to swampland, even quicksand, in order to get where they’re really meant to go.

Photo credit: Sebastian Lemm: Isadora Wolfe, Eliza Littrell, Branislav Henselmann, and Julian Barnett in Johannes Wieland’s Membrane

© 2004 Tobi Tobias