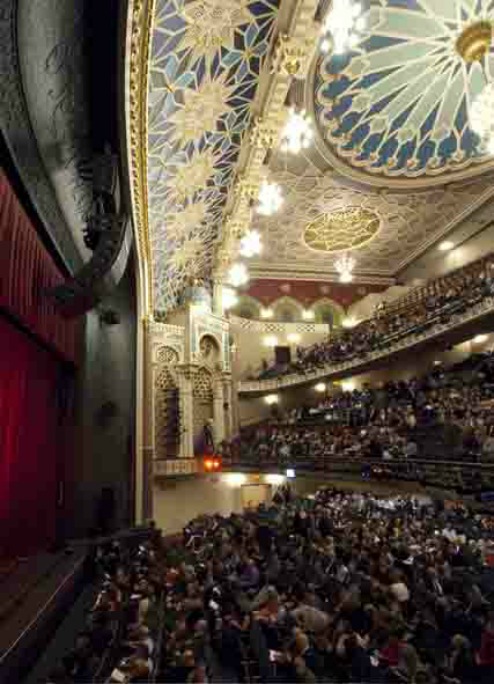

The Forsythe Company / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn, NY / October 26 – 29, 2011

I’ve always shared George Balanchine’s idea that a dance should speak for itself. William Forsythe certainly doesn’t. At BAM last night The Forsythe Company, based in Germany, opened a four-day run of his enigmatically titled work I don’t believe in outer space, created in 2008. Vigorously applauded by a largely pre-middle age audience, it would have remained as impenetrable to me as its title, had I not read the reviews and previews from its earlier showings in London.

Here’s the story I pieced together: The choreographer’s 60th birthday made him conscious of his own mortality. He decided to make a piece to explore the almost unfathomable idea of leaving the world, of simply being absent from everything he knew. (By odd coincidence I had that experience once as a child and naturally have never forgotten it. The notion of non-existence can be terrifying.)

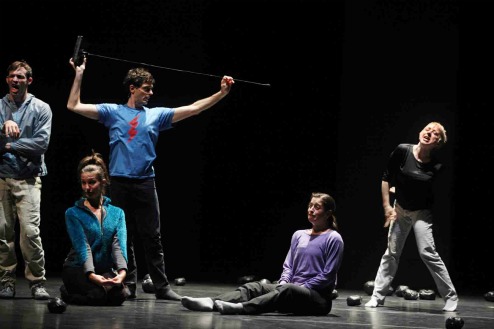

The Forsythe Company in William Forsythe’s I don’t believe in outer space

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

In conjunction with considering his own past and his future prospects, Forsythe explored the idea that the domain he’d be leaving had no meaningful structure or even concrete reality. Things fell apart, came together haphazardly, fell apart again, came together again, and then, maybe, exploded. Everything that happened, happened “as if by chance.” Yet, somehow, life was very much worth living. All of this was accompanied by the notion that at times the goings-on could be amusing.

I don’t believe in outer space uses 17 dancers; live sound and recorded sound (to which the dancers often lip synch); music by Thom Willems; a plainspoken set with dimly lit upstage portals for appearances and disappearances; and, strewn helter-skelter on the stage floor, numerous rough-hewn balls made from the black gaffer tape the backstage crew uses to install flooring and then discards after the show. The balls look like miniature meteorites, fallen from–well, outer space.

The star of the show is Dana Caspersen (Forsythe’s wife). She plays a witchy figure who survives any disaster because of the unquenchable force of her rage. She’s fueled by fury, like creatures of primal evil in the Brothers Grimm. Once you recover from the shock of her presence as this character–the hands like vicious claws, the squatting walk, the loud, grating voice–you’re lured into a shamed admiration of her daring tactics and their success. Caspersen also plays this demon’s alter-ego, a Little Goody Two-Shoes housewife, who doesn’t stand a chance.

Once the major ideas of the piece are presented, Outer Space continues as a series of vignettes. They flow into one another in a manner so subtle that their order seems random–as strings of events so often do in what we think of as real life.

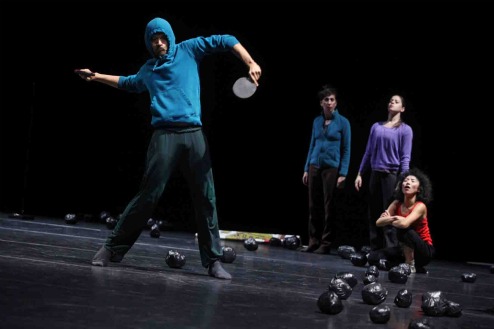

The Forsythe Company in Forsythe’s I don’t believe in outer space

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

In a scene that Alice might have witnessed in Wonderland, two guys play ping-pong. Of course there’s no table, no net, and, what’s more, no ball. But they man their racquets in tandem with the exact sound of the celluloid ball striking an invisible surface. Of course, life being what it is, this absurd match becomes a fatal competition. Even when one of the men captures his partner’s racquet, the two manage to go on “playing.”

At intervals we see a handsomely built male couple–doing what exactly? Making love standing up (more or less) or fighting, in close. The viewer is left to choose which or to settle for the obvious–both. The pair is passionately locked in combat.

Now and then, a petite, fleet woman with a mop of curly dark hair, flashes through the space wearing something red. She’s like a spark of fire briefly animating the prevailing darkness.

As time goes by, events get increasing violent and/or surreal. Finally Yasutake Shimaji introduces some welcome calm into the raucous proceedings. A Japanese-born man, slender and supple, he has a long, haunting, less-is-more solo in which he’s all self-containment and quiet grace.

Suddenly, unexpectedly, matters turn almost sentimental as the narration becomes a long, loving citation of all the things in life you relinquish when you disappear. It may bring tears to your eyes (“no more years, calendars, planning”). You may think it’s sappy (“no more running with your brothers on a railroad track”). I thought the most telling entries on Forsythe’s list were the ones connected to dancing: “no more speed, direction, going, different ways of going”; “no more trees, Fall/fall, things that fall.” And then, the most searing loss of all: “No more touching.”

The 17 dancers who make all this happen are a fabulous bunch. They deserve accolades for power, precision, flexibility, and individual presence. I’m certain that, if I saw them more often, I’d grow fond of the personas they project, just as I did with the performers in Pina Bausch’s early works. Meanwhile, it’s thrilling to see that nearly all of Forsythe’s dancers have their muscles on high alert and that they seem devoted to their boss’s vision. The sight of the full cast simply running cross-stage at top speed can convince you that it’s the journey, not the arrival, that matters.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias