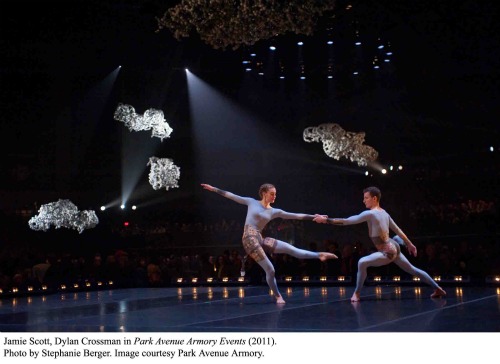

Merce Cunningham Dance Company / Park Avenue Armory, NYC / December 29-31, 2011

A Merce Cunningham Event, as the choreographer described it in a program note, is a performance of about 90 minutes, without intermission, “consist[ing] of complete dances, excerpts of dances from the repertory, and often new sequences for the particular performance and place, with the possibility of several separate activities happening at the same time to allow not so much an evening of dances as the experience of dance.”

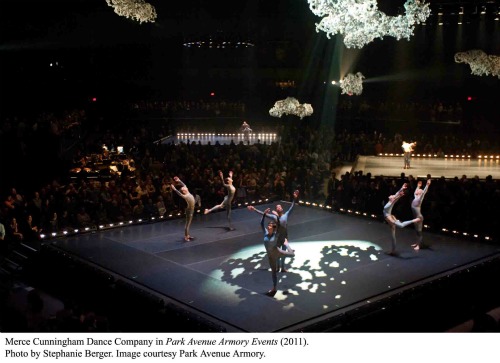

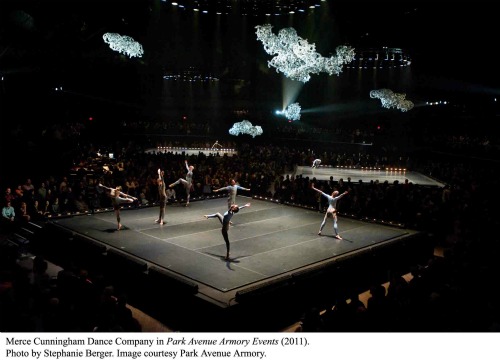

In the course of his career, Cunningham presented almost 800 Events in a grand range of sites worldwide. Fittingly, given the mutability expressed in the form, it was with an Event that the Merce Cunningham Dance Company concluded its existence on New Year’s Eve, December 31, 2011, in New York’s Park Avenue Armory, a cavernous space able to accommodate the three large platforms on which the dancers appeared. (Actually, you could parade the troops there, even a horse-mounted brigade.) Five other performances of this Event, constructed by Robert Swinston, the company’s Director of Choreography, preceded this last goodbye.

In the course of his career, Cunningham presented almost 800 Events in a grand range of sites worldwide. Fittingly, given the mutability expressed in the form, it was with an Event that the Merce Cunningham Dance Company concluded its existence on New Year’s Eve, December 31, 2011, in New York’s Park Avenue Armory, a cavernous space able to accommodate the three large platforms on which the dancers appeared. (Actually, you could parade the troops there, even a horse-mounted brigade.) Five other performances of this Event, constructed by Robert Swinston, the company’s Director of Choreography, preceded this last goodbye.

New music for the Events was contributed by David Behrman, John King, Takehisa Kosugi , and Christian Wolff. Typical of the sound scores played simultaneously with Cunningham’s choreography, these suggested two realms— the future, predominantly, with intermittent excursions into the workings of nature. Lots of annunciatory brass suited the Brobdingnagian space and the solemnity of the occasion.

New music for the Events was contributed by David Behrman, John King, Takehisa Kosugi , and Christian Wolff. Typical of the sound scores played simultaneously with Cunningham’s choreography, these suggested two realms— the future, predominantly, with intermittent excursions into the workings of nature. Lots of annunciatory brass suited the Brobdingnagian space and the solemnity of the occasion.

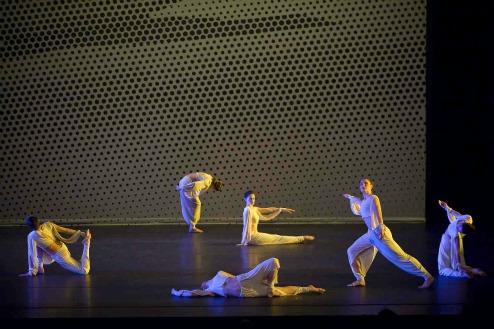

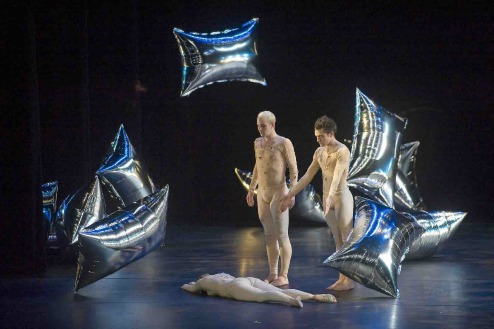

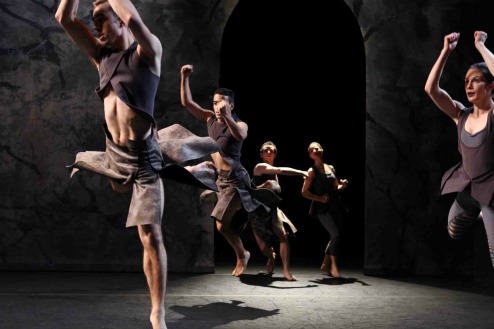

Daniel Arsham studded the lofty height of the space with “clouds”—irregular clusters of off-white to gray balls with the lightweight look of material subject to the impulses of the wind. Anna Finke created the costumes: silky unitards that fit the dancers like second skins, in a subtle palette of gray, blue, beige, and peach. These body stockings were imprinted—most densely at mid-body—with designs suggesting faraway cultures, several of them clearly urban, or intricate tribal designs.

The most important elements of the performance were, of course, the invisible presence of Merce Cunningham and the very much present (and thrilling) dancing provided by Brandon Collwes, Dylan Crossman, Emma Desjardins, Jennifer Goggans, John Hinrichs, Daniel Madoff, Rashaun Mitchell, Marcie Munnerlyn, Krista Nelson, Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Robert Swinston, Melissa Toogood, and Andrea Weber.

The most important elements of the performance were, of course, the invisible presence of Merce Cunningham and the very much present (and thrilling) dancing provided by Brandon Collwes, Dylan Crossman, Emma Desjardins, Jennifer Goggans, John Hinrichs, Daniel Madoff, Rashaun Mitchell, Marcie Munnerlyn, Krista Nelson, Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Robert Swinston, Melissa Toogood, and Andrea Weber.

I chose a seat on a front row bench on one side of the center platform, from which I could get glimpses of what was happening on the other two. Here’s what I saw:

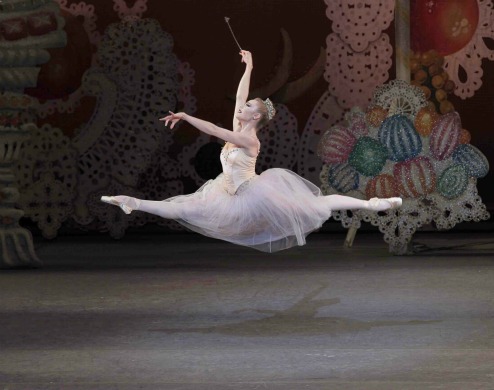

• Leaps springing up from the floor as if it were a trampoline.

• Dancers running, falling, spilling onto the floor again and again, only to repeat the sequence of moves as if exhaustion were not a possibility. They seemed, briefly, to have defeated time and the way time erodes the physical capacity of an ordinary human being.

• The way Cunningham groomed his dancers to shift their weight, and thus their center of gravity, with uncanny speed and daring, through a tilt, a lunge, a fall, or just the move of a single limb or turn of the head.

• The seamless shifts from walking to stalking to running to falling. The seamlessness of spinning turns used to travel through space.

• The intricate beats for the legs and feet that were firm in their clarity, yet had the volatile effect of quicksilver.

• The preternatural equilibrium of long steady balances in which only the toes of one foot made contact with the floor. And, even more extraordinary, the fact that this was treated as no big deal. Indeed, Cunningham’s choreography routinely suppresses evidence of effort. In this it takes an Eastern rather than a Western point of view.

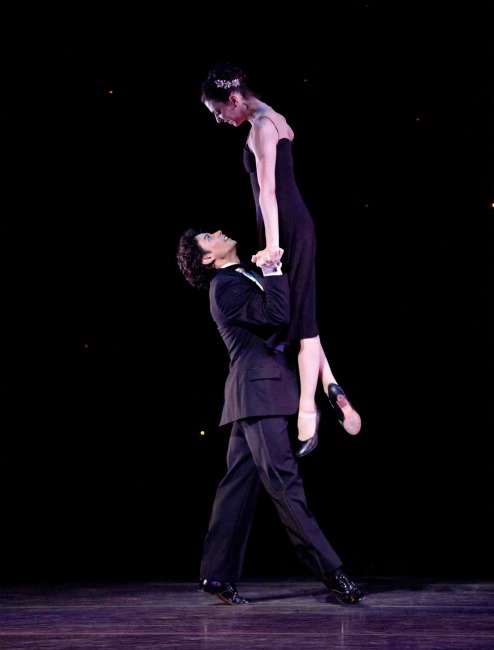

• Partnered work that projected no dramatically conveyed emotion—“Make of it what you will,” Cunningham seemed to be saying—but rather investigated what is possible when one body meets another instead of operating alone. If the viewer wanted to attach a mood or a tale to the material, well that was his or her own affair.

• The absolute trust partners placed in each other at moments of physical risk.

• The articulateness of small things.

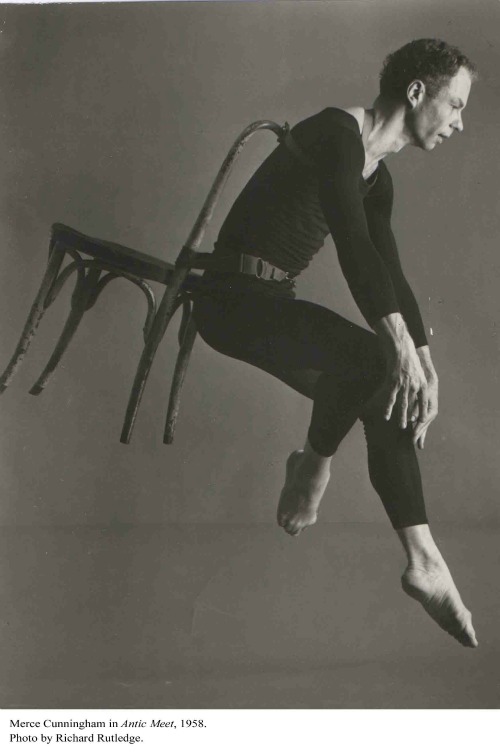

• At one point Robert Swinston, the senior performer, arrived with a “prop,” a slatted wooden folding chair. He sat on it, quiet and contemplative, then proceeded to explore the object’s repertoire. With a delicate touch and attentive care, he got it to tip and spin gently on the outer edge of a single leg. This accomplished, he folded the chair and walked away with it tucked under his arm.

• At one point Robert Swinston, the senior performer, arrived with a “prop,” a slatted wooden folding chair. He sat on it, quiet and contemplative, then proceeded to explore the object’s repertoire. With a delicate touch and attentive care, he got it to tip and spin gently on the outer edge of a single leg. This accomplished, he folded the chair and walked away with it tucked under his arm.

• But is this dancing? someone is bound to ask. That’s a very good question, likely to yield many a provocative answer.

• All the movement is certifiably abstract, of course. Nevertheless it is heady with implications that are not merely about the body, time, and space. Cunningham’s choreography with its hints of mood, emotion, and, yes, even story is an invitation to the viewer’s imagination.

• The spectators ogled the proceedings as if transfixed. Because of the three-platform layout, each with its own arrangements for viewing, and the house lights that were never fully extinguished, the lookers-on seemed to be part of the show, if only a motionless one.

The audience for the closing night Armory Event was even larger than that of the opening night, which I also attended. The first five performances of the run were quickly announced to be sold out. This final one was crammed tight with long-time admirers and curious newbies and proved to be enthusiastic in an unusual way. Fully aware of the historical importance of the occasion, the onlookers applauded and cheered the dancers’ entrance, which was entirely understandable. Irrepressible, however, they also clapped and hooted at the end of everything they took to be a separate segment of the action—a solo, a duet, and so forth—instead of treating “the experience of dance” as a continuum.

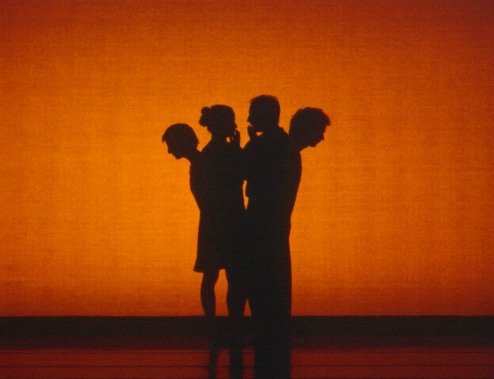

The curtain calls were many, with the dancers lining all four sides of the central platform and then reforming as a tight hand-in-hand circle again and again.

It was hard to believe that this was the last time.

The Events that linger most clearly in my memory took place in Cunningham’s studio in Westbeth, an industrial building converted to give living and working space to artists a good while before Manhattan’s meat-market district became the locus of fashionable young New York.

The Events that linger most clearly in my memory took place in Cunningham’s studio in Westbeth, an industrial building converted to give living and working space to artists a good while before Manhattan’s meat-market district became the locus of fashionable young New York.

Out of respect to the studio’s pristine wooden floor, you took off your shoes at the entrance to the studio, then moved into the performance space where the audience sat on rows of metal folding chairs leading a rickety life on risers or—if enough people came, and they did—foam cushions on the floor.

One magical evening Edwin Denby—among other things, one of the greatest dance critics who ever lived and one of the most beautiful souls I’ve ever known—waved to me and invited me to take the seat he was saving next to him. Once I had edged my way to his side I saw that he’d placed a little pile of magazines under his stockinged feet. He offered me another pile. “Otherwise, he explained, “your feet will get cold.” I believe the magazines were back issues of the New Yorker.

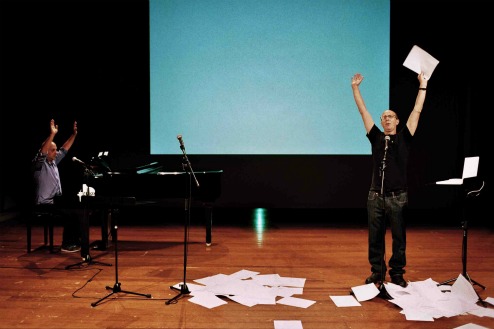

A different musician or musicians were invited to play for each Event. As was Cunningham’s custom with his regular repertory, the music had no formal, pre-ordained connection to the dancing; it simply happened at the same time as the movement. The music itself could be inscrutable; more often than not, though, what the ear heard enriched what the eyes saw, if only in oblique ways. There was certainly no need for décor. What was visible from the studio’s huge windows was sufficient. It was often a glorious—even gaudy—sunset.

The dancers, dressed in unassuming practice clothes, entered the space, faced a variety of points in space (there was no designated “front”), and began to move, performing excerpts from the regular repertory—from several different dances at once, of course.

Some observers, the critics, especially, were eager—even frantic—to know which of Cunningham’s works the various fragments came from. I always thought that was not a very useful or satisfying way to watch an Event. It also created a petty kind of competition on I-know-and-you-don’t lines. As an aide-memoire to the dancers, a sheet noting what would be danced and by whom was posted, usually backstage, a day before each Event, even on the very day. (I wonder if any of these sheets have been saved.)

Some observers, the critics, especially, were eager—even frantic—to know which of Cunningham’s works the various fragments came from. I always thought that was not a very useful or satisfying way to watch an Event. It also created a petty kind of competition on I-know-and-you-don’t lines. As an aide-memoire to the dancers, a sheet noting what would be danced and by whom was posted, usually backstage, a day before each Event, even on the very day. (I wonder if any of these sheets have been saved.)

Occasionally the head and shoulders of the person in front of you partially blocked your view of the dancers. It was in these circumstances that I absorbed what I considered to be a Cunningham principle: The dance was simply what you saw. I stopped twisting my torso and craning my neck, relaxed, and enjoyed the part of the show that was accessible to me at that moment in time and in my position—as well as the dancers’—in space. This attitude was beatifically calming, and that calm made awareness possible.

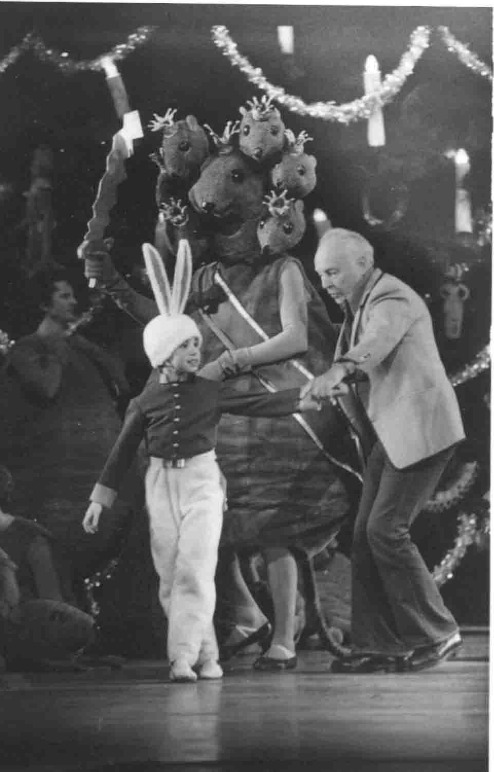

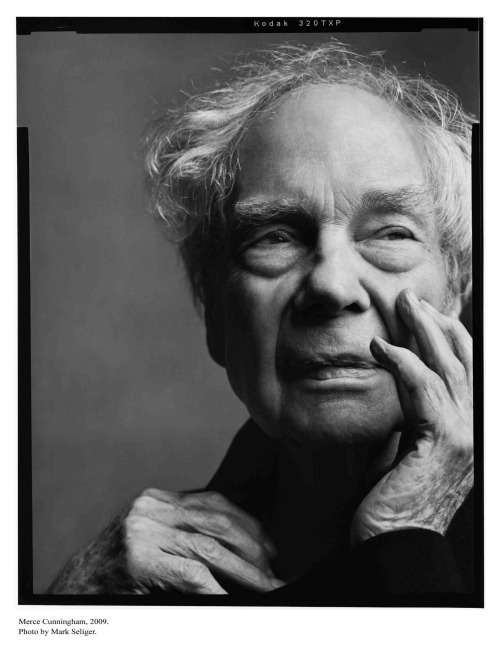

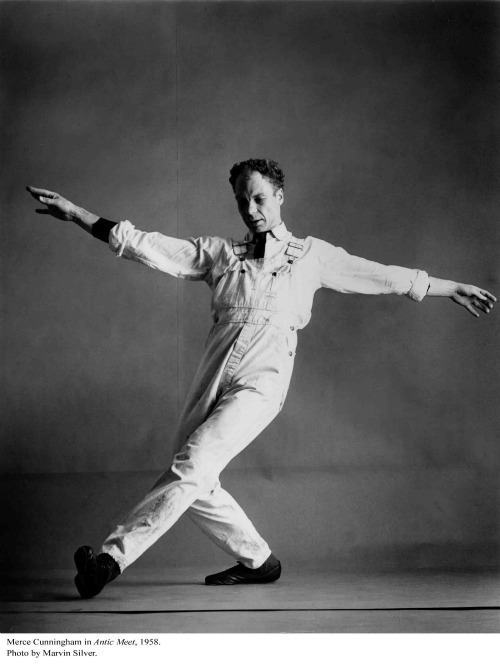

When I started going to these Events Cunningham was still performing. His mass of curling gray hair surrounded his face like a halo. His eyes were riveting. But it was his whole body, taut and alert to every moment in time, that—despite the compromises it had been forced to make with age—offered a wisdom about dance, and simply about being, that made everything else in the space disappear.

© 2012 Tobi Tobias