Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

The second night of the Ashton Celebration featured two dances, both Birmingham Royal Ballet productions, in which the choreographer operated in his free-flowing “barefoot” vein, presumably with Isadora Duncan as his muse. The legendary primogenitor of modern dance was surely past her prime when the 17-year-old Ashton witnessed a handful of her performances in London, but she nevertheless made a tremendous and lasting impression on him—through her musicality, her sense of plastique, her voluptuous weighted quality, her resonance in stillness, and the sheer charismatic force of her conviction.

The second night of the Ashton Celebration featured two dances, both Birmingham Royal Ballet productions, in which the choreographer operated in his free-flowing “barefoot” vein, presumably with Isadora Duncan as his muse. The legendary primogenitor of modern dance was surely past her prime when the 17-year-old Ashton witnessed a handful of her performances in London, but she nevertheless made a tremendous and lasting impression on him—through her musicality, her sense of plastique, her voluptuous weighted quality, her resonance in stillness, and the sheer charismatic force of her conviction.

Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan started out as a little nothing, a pièce d’occasion. From his recollections of Duncan, enlarged by the evocative action drawings artists had made of her—not attempting to replicate Duncan’s own simple choreography but freely extrapolating from it—Ashton set a single waltz on the superb dancer-actress Lynn Seymour for a gala in 1975. It was recognized as a gem and, the following year, he expanded the material into a suite, which entered the repertory of the Royal Ballet.

Seymour was extraordinary in the role. Even photographs, which inevitably diminish the vitality of the dancing they record, show that. One, by Peggy Leder, seizes the moment in which the Isadora figure rushes straight forward toward the audience, arms outstretched, rose petals cascading from her hands, head flung back to expose a strong, sensuous throat, the advance of the body led by a magisterial foot that confidently acknowledges gravity’s claim.

The BRB’s staging was danced by Molly Smolen, who had the immense good fortune to have Seymour coach her in the role. The result was glorious. Smolen moves with exorbitant energy, capturing the lion-hearted quality we associate with Duncan. What’s more, she makes the movement look impetuous; for a moment you think she might be inventing it on the spot. I suspect this quality characterized Duncan’s performances, which may well have encompassed a certain measure of improvisation. Running about the stage in a curving path, trailing behind her a huge swath of fabric that echoes the glowing peach hue of her Grecian tunic, Smolen seems to have turned herself into all things that ripple with life: wind, waves, flames. At times, she’s Dionysian, the incarnation of primal sexual instincts. Elsewhere, in repose, she seems to find the still center in which a single person can imagine herself to be the heart of the universe.

Unlike Duncan, and unlike Seymour, who danced with generously fleshed bodies, Smolen has an upper body that appears as slender as a stripling’s, and her arms retain some of the charming angularity and awkwardness of adolescence. Astutely, she uses this deviation from the generic Isadora image to her advantage. She lets the gaucheness set off the prevailing voluptuousness of the material and, with it, suggests something of the stubborn, single-minded rebelliousness, usually confined to impulse-driven youth, that characterized Duncan’s personality and actions, onstage and off, throughout her life.

Much credit for the pleasure and excitement Smolen generates in this Ashtonian gem is due to Seymour—for serving as mentor to an interpretation so valid for the ballet yet so unlike her own.

Dante Sonata, rescued from oblivion on the initiative of the BRB’s director, David Bintley, was choreographed in 1940, as Britain waited for the bombs of World War II to obliterate the happier life it once knew. A somber mood due to the recent death of his mother augmented Ashton’s response to, as he put it, “the whole stupidity and devastation of war.” (On another occasion, he used the word futility.) So the ballet’s juxtaposition of the Children of Light and the Children of Darkness is no good-guys-vs.-bad affair, but rather a lose-lose situation, in which, though the Dark figures are patently the aggressors, both tribes are ravaged and all but destroyed. Although the work is, admittedly, something of a period piece—with lots of Massine-derived, Robert Helpmann-style expressionism in it—it is piercingly relevant today. It should be required viewing, for instance, for anyone participating in the upcoming national conventions of our major political parties, alternating in repertory, perhaps, with Kurt Jooss’s The Green Table.

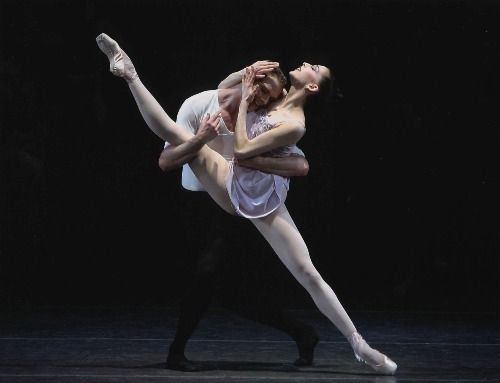

The ballet is based on the Inferno and Purgatorio sections of Dante’s Divine Comedy and set to music by Lizst that refers to the Dante via a poem by Victor Hugo. The choreography, like the costumes and backdrop by Ashton’s beloved collaborator Sophie Fedorovitch, are influenced by celebrated illustrators of Dante: William Blake, Gustav Doré, and John Flaxman. The female Children of Light are visions of innocence in unadorned translucent white gowns; their male partners, princes of purity, complement them in snowy chemises with blouson sleeves and immaculate danseur noble tights. The Children of Darkness favor black webbing and grimaces that transform their faces into ferocious (or is it agonized?) masks. The choreography owes most, however, to Isadora Duncan, not simply because most of the dancers are barefoot and the women’s long hair is unbound, but also—and primarily—for its emotion-invoking plasticity and its tidal surges of movement.

“What one mostly remembers from Dante Sonata,” David Vaughan writes in Frederick Ashton and His Ballets, “are its images of shame and suffering, turmoil and torment.” I can’t put it better and would merely add to it notice of the effective patterns Ashton designed for the warring groups—now starkly geometrical, as in Martha Graham’s 1931 Primitive Mysteries; now linked and braided as in Bronislava Nijinska’s 1923 Les Noces. Beyond that, I recall particularly the sheer pictorial beauty of the several ways in which the participants shield their faces, depicting grief, and the odd yet very apt things occasionally done by a single figure suddenly sprung from the ensemble—a woman, for example, nearly berserk with anguish, thrashing the air with her arms as she runs, as if beating frenetically on a giant invisible drum. This aspect of the choreography eerily prefigures certain traits in Mark Morris.

As I’ve indicated, Dante Sonata works as a polemic piece as well as on a purely aesthetic plane. Concerning the latter, the most intriguing aspect of the ballet may be its intensely pictorial nature. It ends, for example, with the simultaneous crucifixion of the male leaders of the Darkness and Light clans, but the shock and horror of the action is muted by the fact that the scene makes you think, first and foremost, of paintings of the subject you’ve viewed in the medieval and Renaissance sections of the world’s great museums.

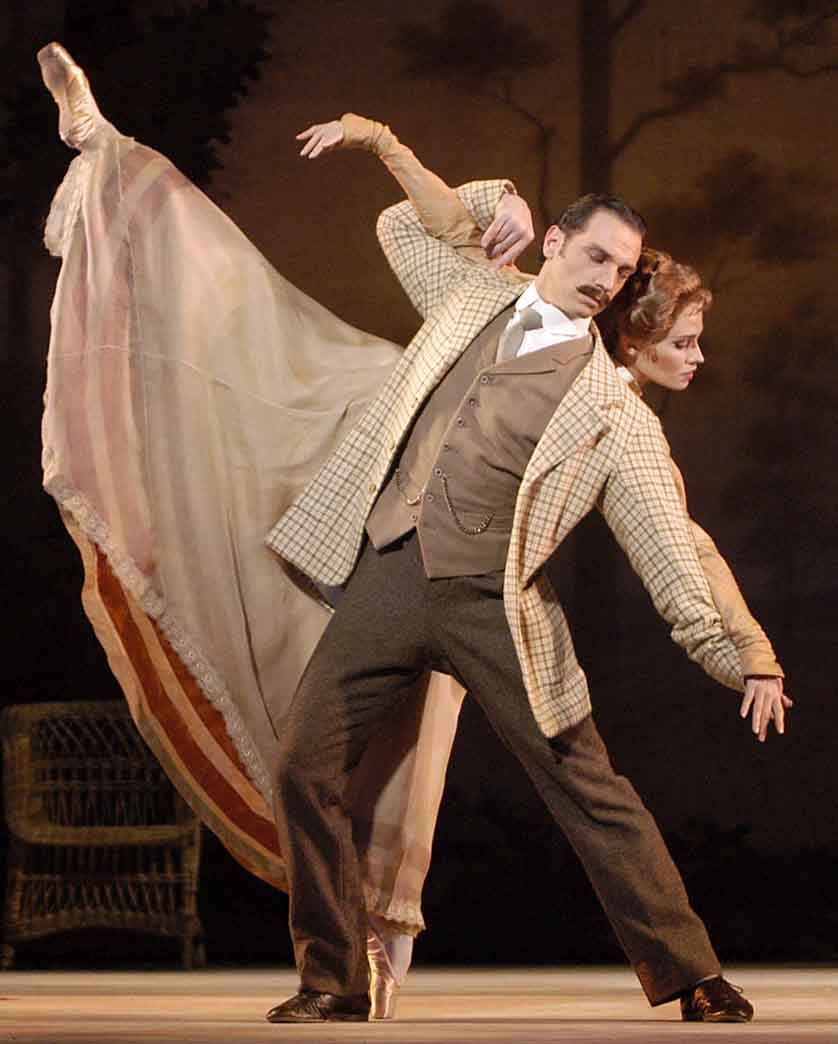

Photo credit: Bill Cooper: Molly Smolen in the Birmingham Royal Ballet’s production of Frederick Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

The ballet is set to the Edward Elgar score from which it takes its name, a suite of musical character studies of individuals in the composer’s circle. Ashton places the action in Worcester in 1898, the locale and time of the score’s composition, in the house and adjacent garden where Elgar is surrounded by his near and dear: his care-filled constant wife; a man who is his heart’s comrade; several endearingly eccentric friends (whose very absurdity invites affection); several ladies whose relationship to Elgar, though intentionally kept enigmatic, suggests the many faces of love (a flirtatious child-woman, a serene mature one offering a sensuousness that needn’t ignite, an ephemeral muse), and an assorted flurry of neighbors and functionaries.

The ballet is set to the Edward Elgar score from which it takes its name, a suite of musical character studies of individuals in the composer’s circle. Ashton places the action in Worcester in 1898, the locale and time of the score’s composition, in the house and adjacent garden where Elgar is surrounded by his near and dear: his care-filled constant wife; a man who is his heart’s comrade; several endearingly eccentric friends (whose very absurdity invites affection); several ladies whose relationship to Elgar, though intentionally kept enigmatic, suggests the many faces of love (a flirtatious child-woman, a serene mature one offering a sensuousness that needn’t ignite, an ephemeral muse), and an assorted flurry of neighbors and functionaries.

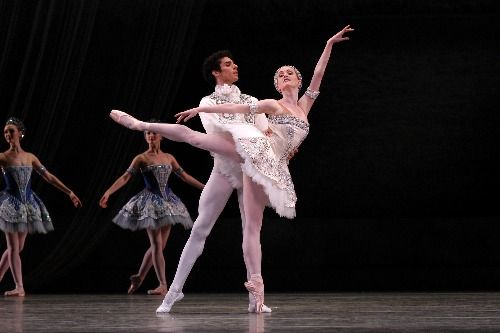

Gilliland, just turned 17, comes from Minnesota and from a distinguished matrilineage. Her grandmother, the late dancer and choreographer Loyce Houlton, founded Minnesota Dance Theater, blending the purity and lyricism of classical ballet with the deep texture of modern dance. Her mother, Lisa Houlton, who now runs that company, was herself a lovely dancer schooled in both modes. Gilliland, however, might be a changeling child. She seems to belong entirely to the ballet domain, indeed to a particularly rarefied part of it. Exceptionally tall, exceptionally slender, her small head poised like a jewel on her long neck, her spine as flexible as a young willow, she’s an ethereal, otherworldly creature. As the “Dark Angel” in Serenade, she seems to exist in a dream that is half the creation of Balanchine and Tchaikovsky, half her own fantasy. Even heading up the leg-flaunting chorus of Wrens in Union Jack, She manages to remain a little shy, luminous in her innocence. She will remind veteran observers of Allegra Kent.

Gilliland, just turned 17, comes from Minnesota and from a distinguished matrilineage. Her grandmother, the late dancer and choreographer Loyce Houlton, founded Minnesota Dance Theater, blending the purity and lyricism of classical ballet with the deep texture of modern dance. Her mother, Lisa Houlton, who now runs that company, was herself a lovely dancer schooled in both modes. Gilliland, however, might be a changeling child. She seems to belong entirely to the ballet domain, indeed to a particularly rarefied part of it. Exceptionally tall, exceptionally slender, her small head poised like a jewel on her long neck, her spine as flexible as a young willow, she’s an ethereal, otherworldly creature. As the “Dark Angel” in Serenade, she seems to exist in a dream that is half the creation of Balanchine and Tchaikovsky, half her own fantasy. Even heading up the leg-flaunting chorus of Wrens in Union Jack, She manages to remain a little shy, luminous in her innocence. She will remind veteran observers of Allegra Kent.