Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater / City Center, NYC / November 28 – December 30, 2012

I went to an Ailey matinee and the space was filled with children, onstage and off. The dance-trained kids were inserted into Revelations where the choreography had no need of them, yet they seemed beautifully schooled, spines marvelously erect yet flexible, without a glimmer of ersatz showbiz in them, and, like the New York City Ballet’s wunderkinder, utterly at home being ogled by a huge audience—from classmates and loved ones to hordes of strangers. Whatever the Ailey’s school is doing to produce this effect, other schools might usefully take note. Yes, even classical ballet schools.

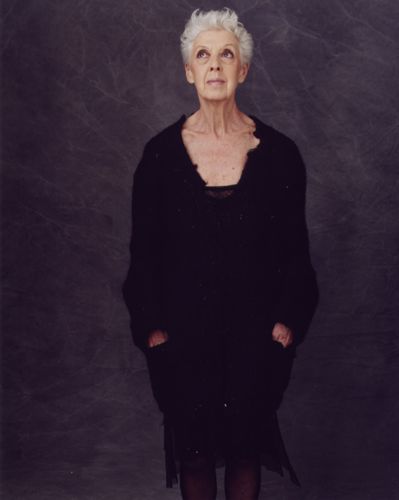

Dancers of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, led by Jacqueline Green, in Kyle Abraham’s new Another Night

Dancers of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, led by Jacqueline Green, in Kyle Abraham’s new Another Night

Photo: Paul Kolnik

I was at the theater especially to see to see Another Night, by the youngish, much-feted choreographer Kyle Abraham. It’s set to Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers’ rendition of Dizzy Gillespie’s “A Night in Tunisia.” (Hence, I assume, the title of the dance.) But here Abraham’s often-daring subject matter and tone were oddly defanged, perhaps relegated to less Big Deal venues. The choreographer is also frequently noted for freely combining different dance genres, but that is done so regularly nowadays, we hardly notice. At any rate, I was underwhelmed by this piece, which seemed to fit right in with much of the earlier Ailey repertory.

Of course there were lovely passages in the dance. Not for a moment would you doubt either Abraham’s skill or imagination. He translates the dancers’ extraordinary physical strength into sailing through the air—often in complex contortions—and landing with delicacy and confidence. And he takes the humanity these dancers display the moment their feet hit the floor and their upper bodies reach into space and makes it something every pedestrian can share.

The dancing itself was no less terrific than we’ve learned to expect from the Ailey, with each of the performing artists making his or her work unique—as if only this body, this individual way of executing a step or phrase, this indication of intent made an essential contribution to the effect of the whole.

This dichotomy in quality between mediocre choreography and stellar performance is a situation that has long plagued the company, but as the repertory continues to expand—not simply in number, but in genre–the tide may turn. Meanwhile the Ailey keeps putting on shows that keep a world-wide audience watching.

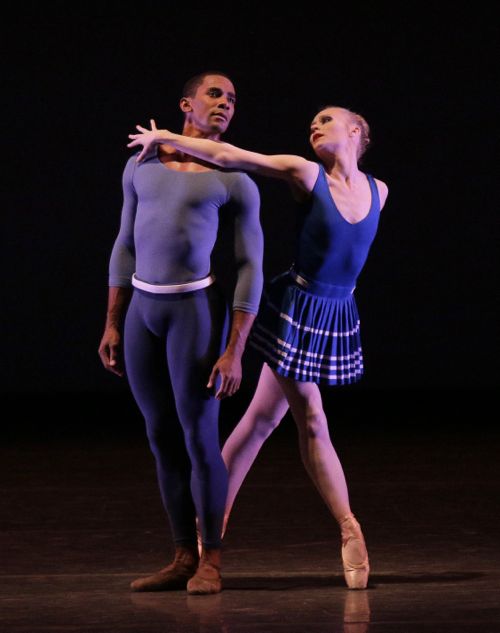

On December 9, Renee Robinson, a member of the Ailey company for 31 years, celebrated that amazingly long tenure with the troupe, surrounded by the splendid and loving efforts of colleagues who had danced beside her at various stages of her career.

Renee Robinson, veteran of 31 years with the Ailey company, in the founder’s classic Revelations

Renee Robinson, veteran of 31 years with the Ailey company, in the founder’s classic Revelations

Photo: Andrew Eccles

For this retirement-from-the-company’s-stage event (she hasn’t announced her plans for the future yet) Robinson herself took on key roles in the 1974 Night Creature (set to music by Duke Ellington) and in Revelations (created, in 1961, to traditional songs of the black community). In Night Creature the lady she plays is sexy as all get-out (yet, typically of Robinson, not raunchy) and convinced that she’ll emerge a star. Robinson herself says she had to travel a long road to stardom, but I think the essentials were already there by the time she studied at the Jones-Haywood School of Ballet, the only classical dance academy in her home town of Washington, DC, that accepted black dancers. (Interestingly, she has transferred from classical to modern dance smoothly. That alone is quite a feat.)

In the “Wading in the Water” section of Revelations, Robinson uses her umbrella—with its generous white fabric—almost as a fifth limb, a mark of herself as a beauty created by wisdom and experience. In the irresistible finale of the piece, “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham,” as its community gathers for what promises to be ebullient worship, she demonstrated the joyful sassiness—greeting her girlfriends with the camaraderie that, I suspect, has saved many a troubled soul and keeping the menfolk from taking “friendship” too far.

Highlights of Robinson’s fellow dancers’ efforts included Matthew Rushing, an unusually romantic dancer in the male contingent—one of the few who looks as if could never go to war—performing “A Song for You” with loving—and specific—devotion. Linda Celeste Sims, another longtime company favorite, danced an excerpt from Alvin Ailey’s famous 1971 solo Cry—an abstract, yet viscerally touching account of a black woman’s experience, surviving a life without privileges. The piece was done on this occasion with two additional women echoing the main figure. (The Ailey has never yet admitted to itself that “more” is often “too much.”)

The mood of the program and its reception was rejoicing—celebrating a long life in a merciless art that, at its best, provides ecstasy—for both performers and their witnesses. Not a tear was shed, at least not onstage.

Renee Robinson

Renee Robinson

Photo: Andrew Eccles

© 2012 Tobi Tobias