Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater / City Center, NYC / December 2, 2009 – January 3, 2010

Beginning with the opening night gala, I visited the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (“The Ailey,” to its friends) many times during its month-long City Center season, which celebrated Judith Jamison’s 20-year tenure as artistic director. Jamison will become “artistic director emerita” at the end of this year. Her successor has not yet been named, but it will be hard to find her equal–first as a star dancer, then as a leader with unassailable authority, a sharp eye for talent, a tough work ethic, and irresistible charisma.

Opening night felt relatively subdued compared to the high-voltage atmosphere generated by such occasions in recent years. Its first half was devoted to generic speeches, excerpts from Jamison’s own so-so choreography, and a pièce d’occasion made in her honor by Robert Battle.

Battle’s offering, a male duet titled Anew, may have been about succession. If so, too subtly so. Its only striking element was the poised control, cloaking ferocious energy, of Jamar Roberts and Clifton Brown as they prowled through their space like big cats in the wild. Traditionally, this has been a skill of just about every member of the company, male and female, black and white. Jamison has brought it to a full flowering, as she has the leaps that shoot across uncanny stretches of space; and the sky-high leg extensions from a daringly tilted body. Performance after performance, Jamison’s dancers claim the right to be called acrobats of God.

Excitement quickened in the second half of the program, thanks to a knock-out performance of Ailey’s own signature piece, the 1960 Revelations. One of its highlights was Amos J. Machanic, Jr.’s exquisite and original rendering of “I Wanna Be Ready,” that gut-cruncher of a solo in which the sheer physical challenge (made, of course, to look effortless, even delicate) comes across as a humble, poignant cry of faith. More thrilling yet was the familiar, though never twice the same, sight of Linda Celeste Sims and Glenn Allen Sims performing the “Fix Me, Jesus” duet, which they’ve evolved to the point of incandescence. She lets herself fall from a succession of precarious positions, trusting he’ll there to save her from self-destruction, and he is, but these and many another feat–of coordination, of balance–have become as refined as a silkworm’s threads.

Overall, the company’s technique seems to be suddenly stronger and clearer than I’ve ever seen it. Often when this occurs in a dance troupe, the technical “improvement” is accompanied by the sacrifice of the dancers’ individuality, the texture of their movement, and that invisible but essential quality of soul. (Today’s New York City Ballet is a significant example.) The Ailey, on the other hand, seems to have increased its physical exactitude in order to make the choreographers’ (and dancers’) visions more piercing.

Repertory remains the Ailey’s perennial problem. This was clear from the Best of 20 Years anthology, which presented excerpts from pieces Jamison commissioned, revived (Alvin Ailey’s included), or acquired during her two decades as artistic director. The deficiency surfaced again in two of the three works given their premieres this season. If you can look behind the stunning performances the dancers invariably give it, the choreography offered by the Ailey is, with few exceptions, thin in invention, and stymied by prefabricated emotional agendas.

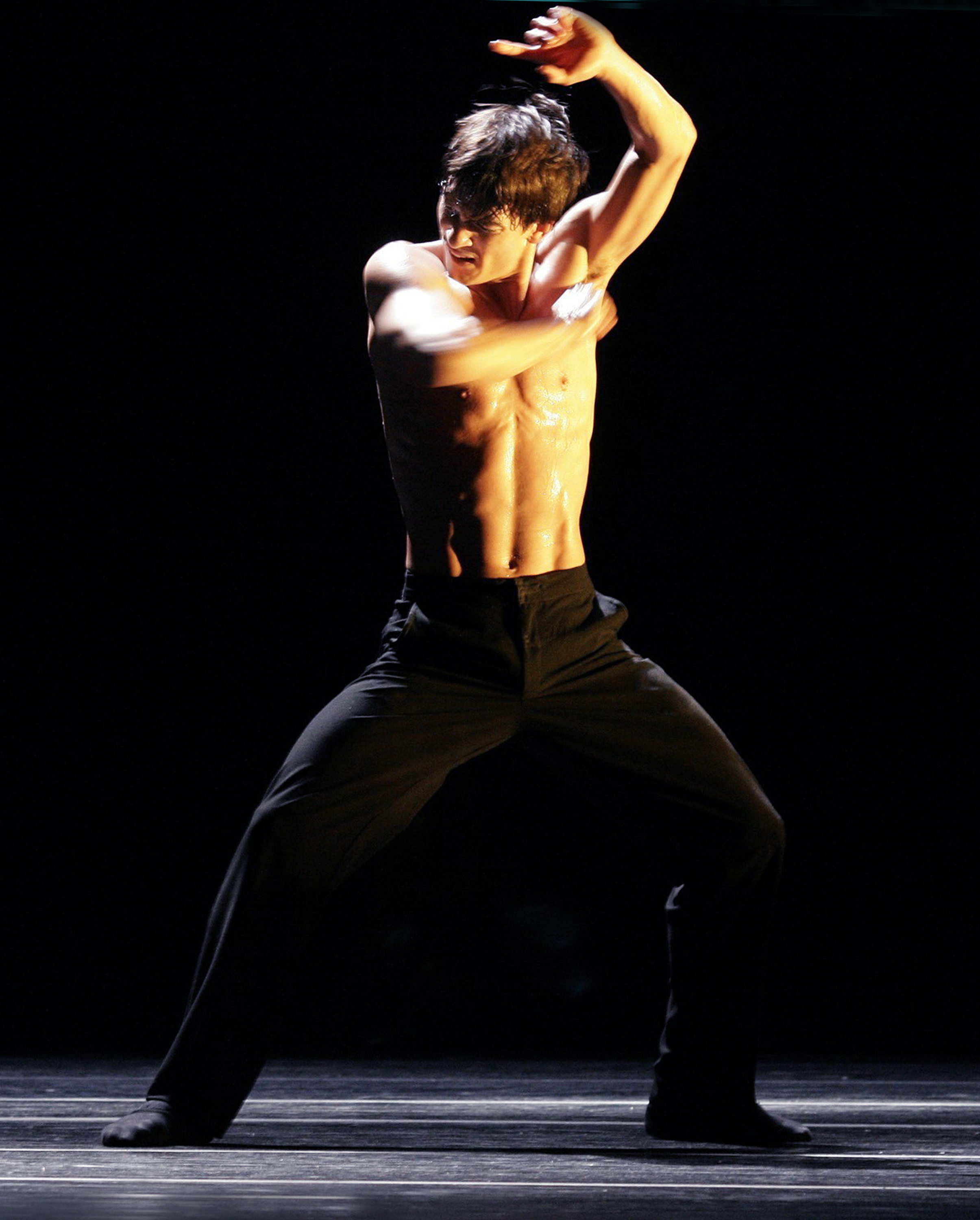

Jamar Roberts in Judith Jamison’s Among Us

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Jamison’s own Among Us (Private Spaces: Public Places), to music by Eric Lewis, shows us the fantasies of people at an (art) exhibition, the art naïf pictures being by Jamison. Granted, the encounters do include the traditional museum pick-up, but half of them remained inexplicable to me, even on a second viewing. The imaginary shenanigans are encouraged by a genie, played by Clifton Brown, a dancer so beautiful and gifted he can even get away with a tall blue feather waving from the top of his skull.

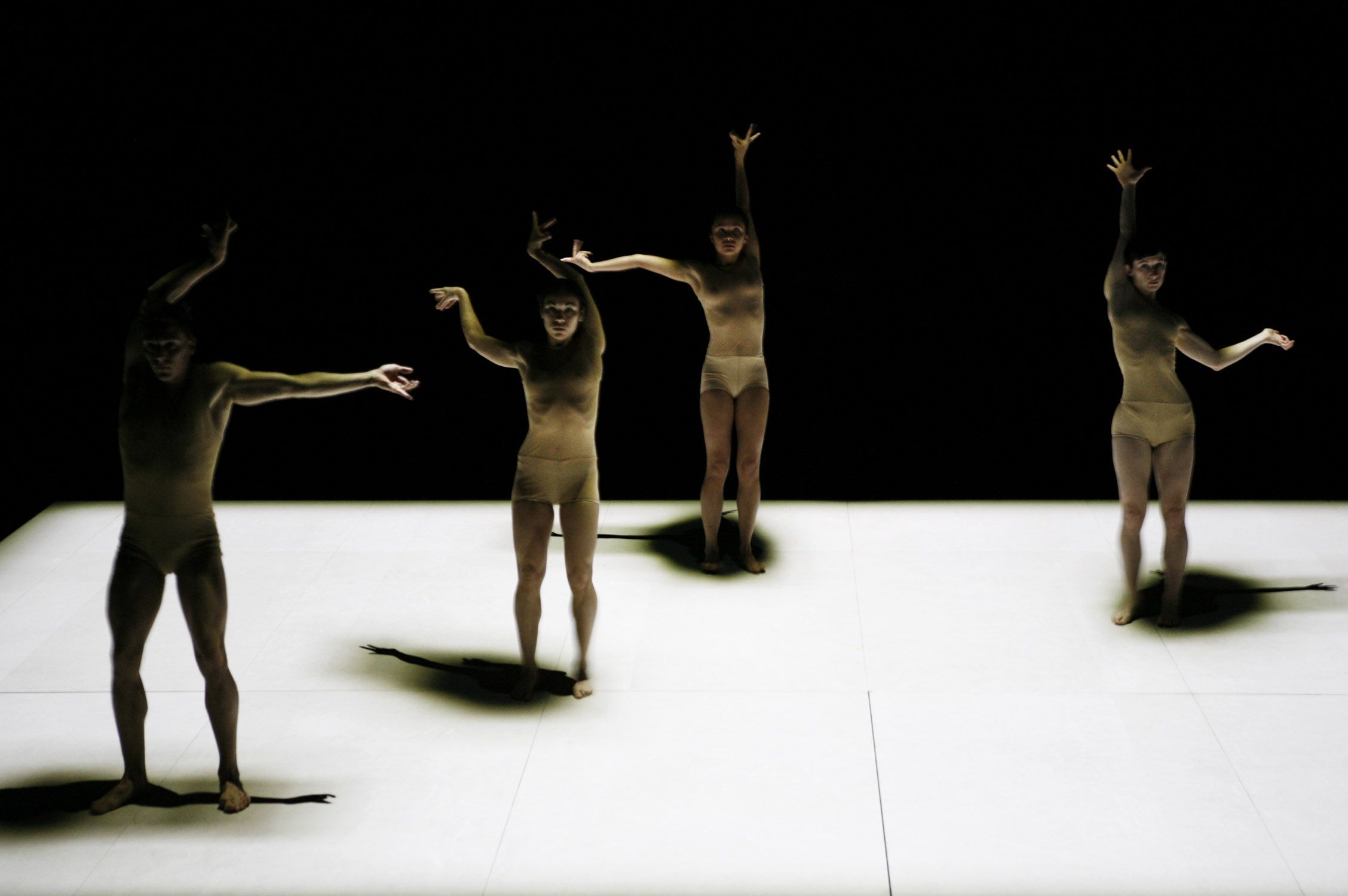

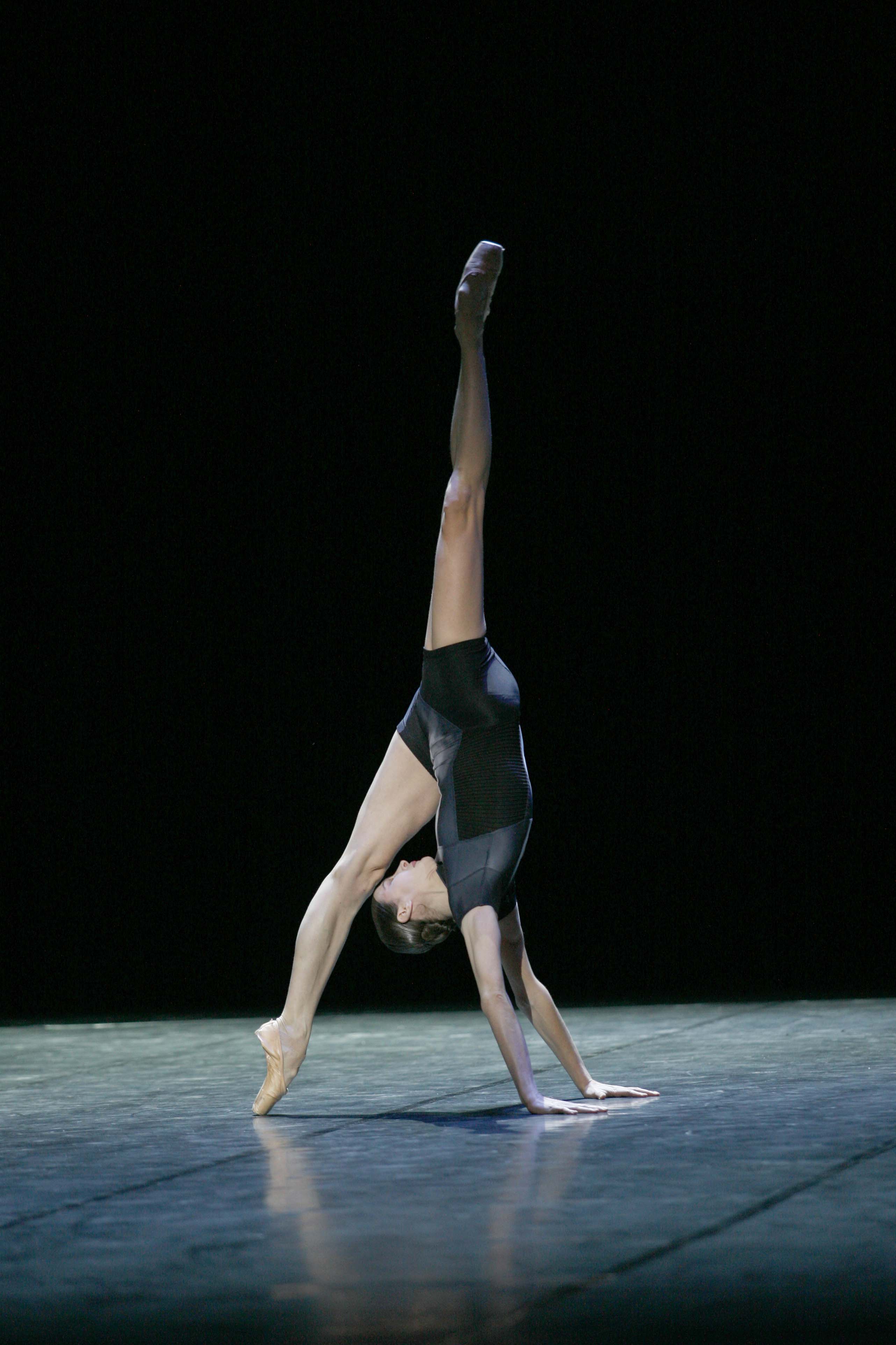

Linda Celeste in Judith Jamison’s Among Us

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The movement vocabulary draws from ballet, jazz, Horton via Ailey, and middle-eastern genres; despite this generous pluralism, the choreography falls flat. The most compelling dancing in the show comes from Linda Celeste Sims, all filigreed whirling in a ravishing flamingo-hued dress with a lushly flared skirt, and Hope Boykin, somberly expressive, in a deep purple business suit with an ingeniously pleated vent in its skirt that allows and draws the eye to her full-bodied movement. As I’ve indicated, the costumes, by Paul Tazewell, are marvelous, but clothes alone don’t make a viable dance.

Uptown, by Matthew Rushing, one of the company’s senior and most revered dancers, attempts to chronicle the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, in which a confluence of African-Americans made achievements in the arts (Langston Hughes, Josephine Baker) and social concerns (W.E.B Du Bois) that would influence generations to come. Both the street life and partying life of the period were memorably sassy too. Perhaps inevitably, the subject required as much talking as dancing–so the piece has a narrator (the hyper-fueled Abdur-Rahim Jackson at the performance I saw), who both speaks and moves, and recordings of the greats. Not unexpectedly, the choreography often falls prey to the impossible task of miming what is spoken. Overall, the result is more like an educational documentary film than a real live dance. By next season it might be playing to kids in middle school.

Nevertheless, Uptown contains occasional passages–the “Weary Blues” section, for instance–that suggest Rushing has some flair for choreography. So I hope he’ll be given another chance–perhaps in a workshop situation, to lessen the pressures of a big, important, and expensive production–to create a work that isn’t so dependent on library research.

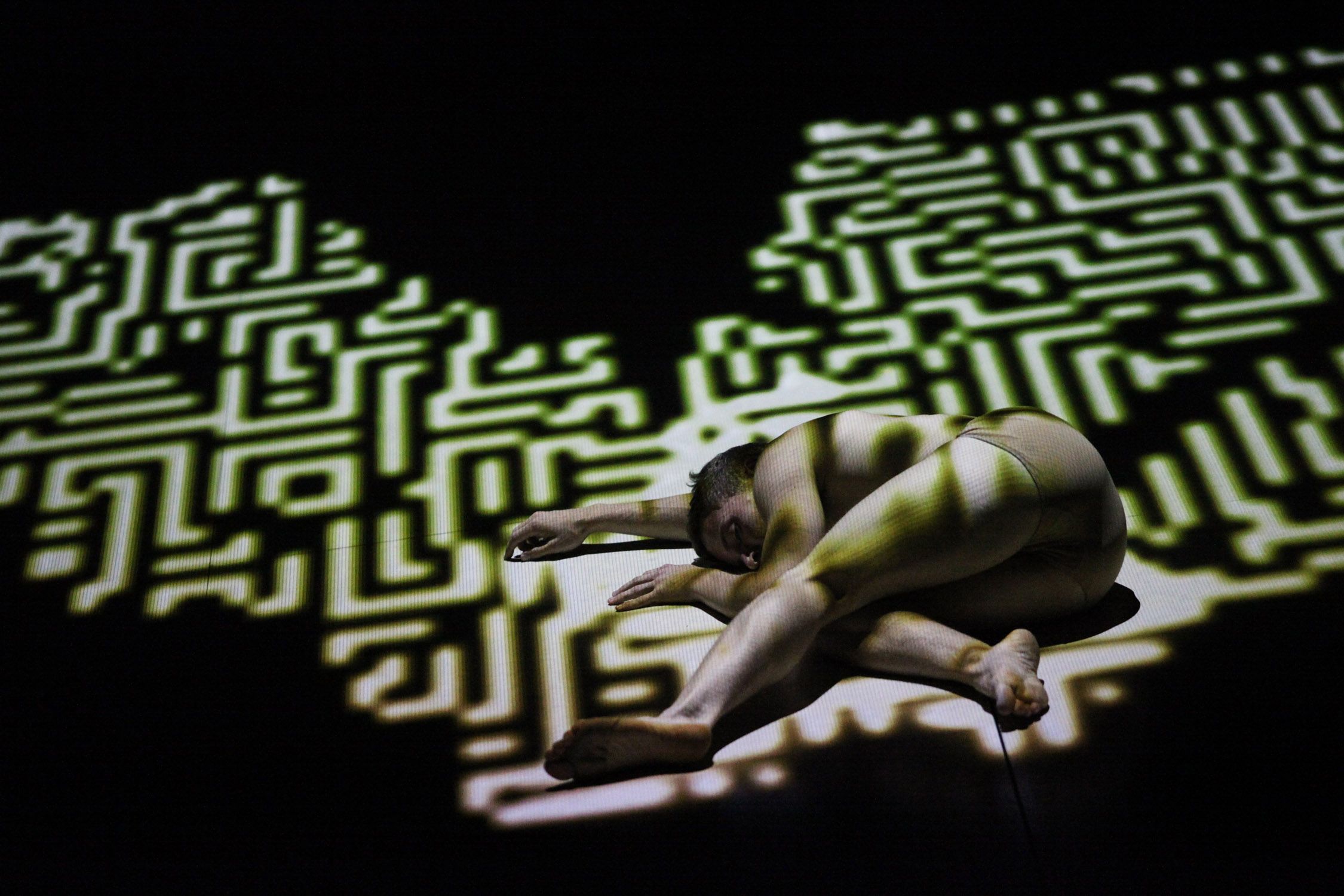

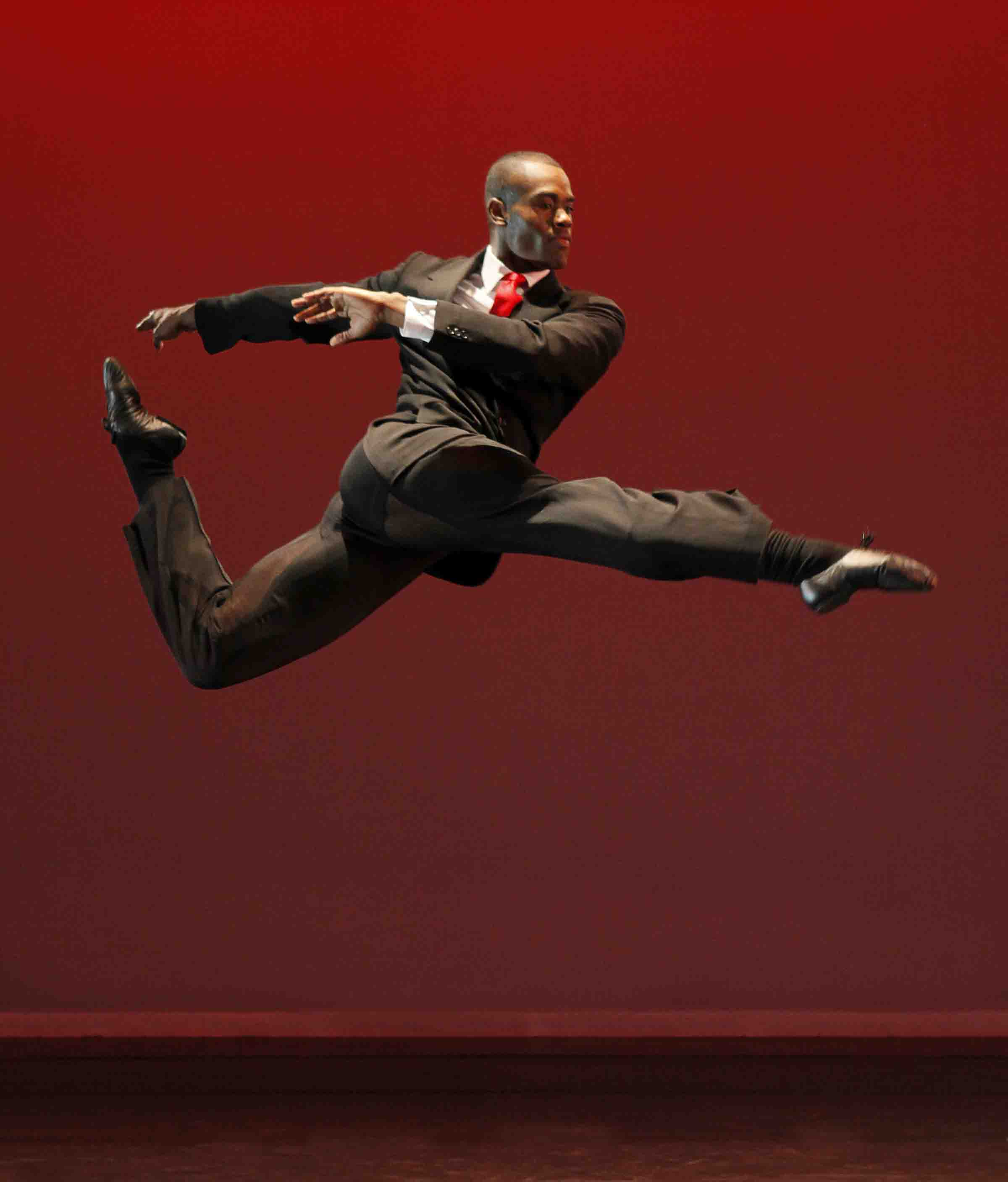

Matthew Rushing in Ronald K. Brown’s Dancing Spirit

Photo: Paul Kolnik

By far the best of the new works was Ronald K. Brown’s Dancing Spirit, its title taken from Jamison’s 1993 memoir, its score assembled from jazz, rock, and fusion music of then and now. Brown has created works for many companies in addition to the Ailey and maintains a troupe of his own, Evidence. Despite Brown’s slew of commitments, Jamison’s successor would be a fool not to co-opt him for the position of Choreographer in Residence at the Ailey. The move would benefit all concerned.

Dancing Spirit opens with the entrance of a peaceable man in white, who establishes an area of calm in a teardrop spotlight. A woman follows him, then another man, and so on. The slow procession has a ritualistic air–Brown’s dances are often spiritual–and you breathe deeper as it continues.

Then a punchier rhythm invites additional dancers into the stage space. Arms are quietly raised to the heavens, then strike out forcefully on the diagonal. The group’s movement suavely incorporates elements from the dances of the African diaspora and American modern dance; there’s a touch of jazz here, a hint of ballet there. Torsos ripple, hips sway, inviting the viewer imagine her- or himself part of this community, which depicts the realm of the spirit while giving the Earth its due.

Even so, the loveliest and most remarkable quality of the choreography is Brown’s confidence (that of a born architect) with the groupings and patterns the bodies make in space. A penultimate section is all throbbing percussion, but just when you think this climax will escalate until it sets fire to the theater, the dancers arrange themselves gently into a horizontal line downstage, standing still and self-possessed.

NOTE: The above article, commissioned by Voice of Dance, comes to you so late because VOD has held it without posting it since its timely submission on December 24. Not only has VOD failed to post the piece, it has also failed to pay me for it and for my previous article on its site, “Morphoses Falters,” a review of Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company, which it did post. Such is the lot of the free-lance dance writer.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias