Even after my daughter, a School of American Ballet student, outgrew (literally–the costumes have to fit) a string of kiddie roles in Balanchine’s Nutcracker–Angel, Soldier, Polichinelle, Candy Cane–I still made many a trip to Lincoln Center for New York City Ballet’s annual offering of the holiday production. As a dance critic, I’ve found the ballet infinitely engaging and worth considering from myriad angles. This season I’ve gone twice, both times to focus on the company dancer who fascinates me most these days: Sara Mearns, who is appearing in two roles–Dewdrop and the Sugarplum Fairy.

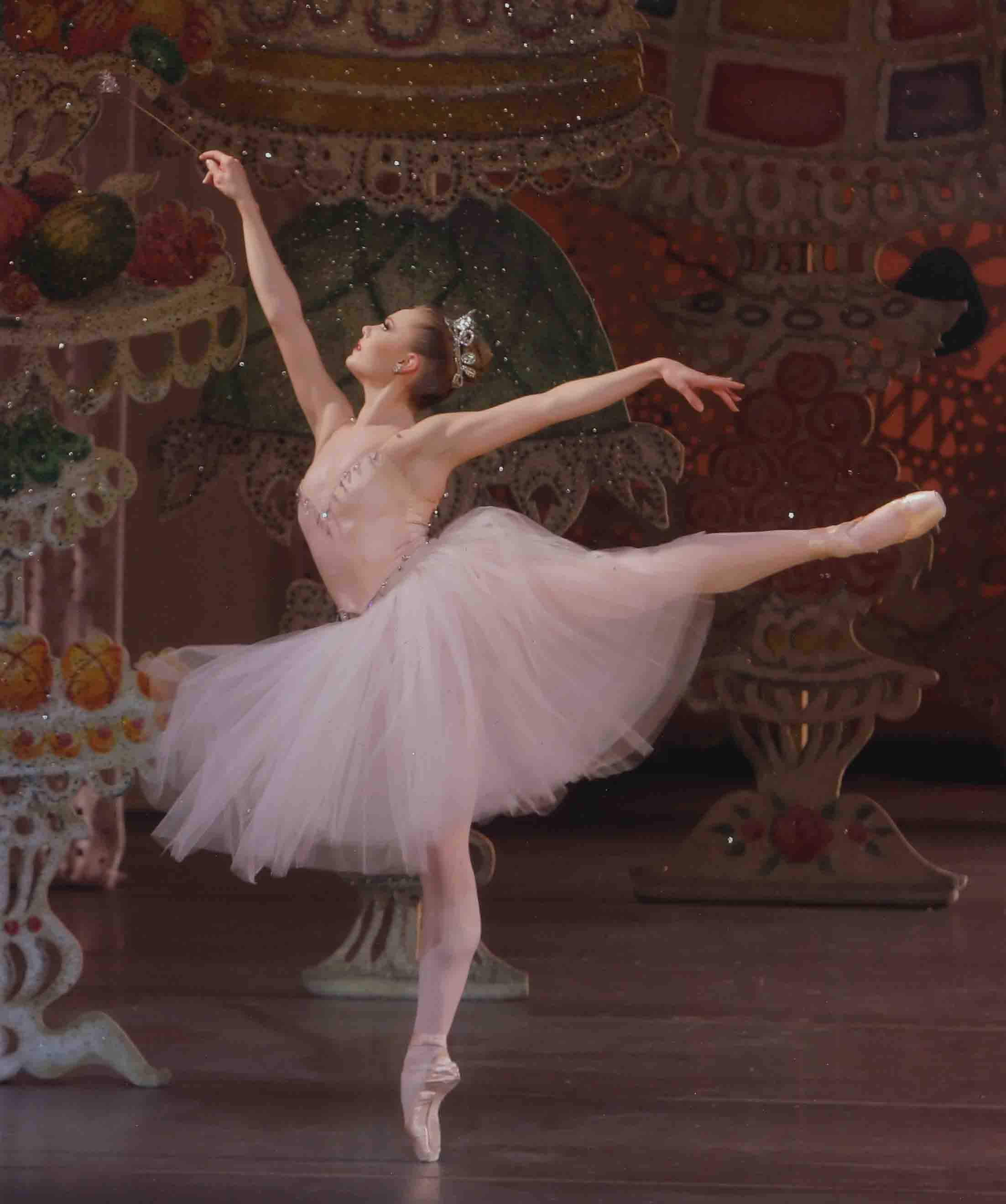

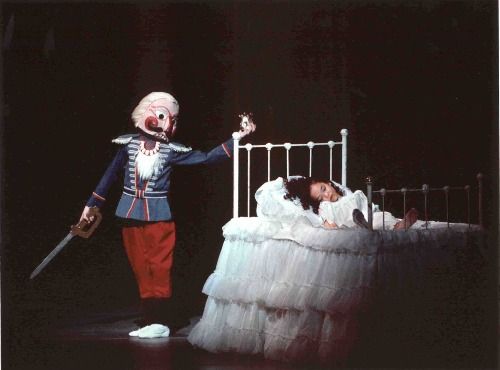

Enchanting the Children: New York City Ballet’s Sara Mearns as Dewdrop, in George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker

Photo: Paul Kolnik

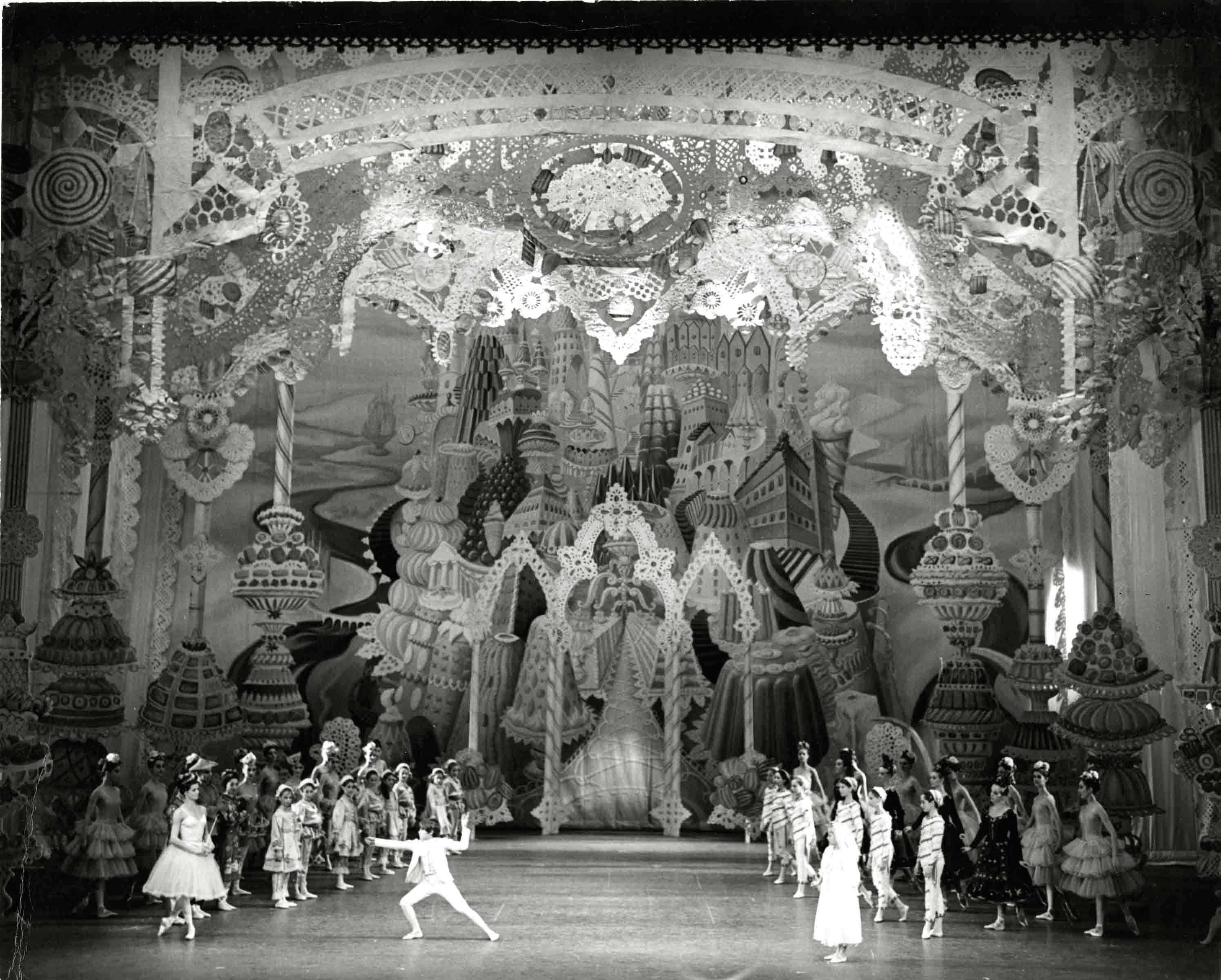

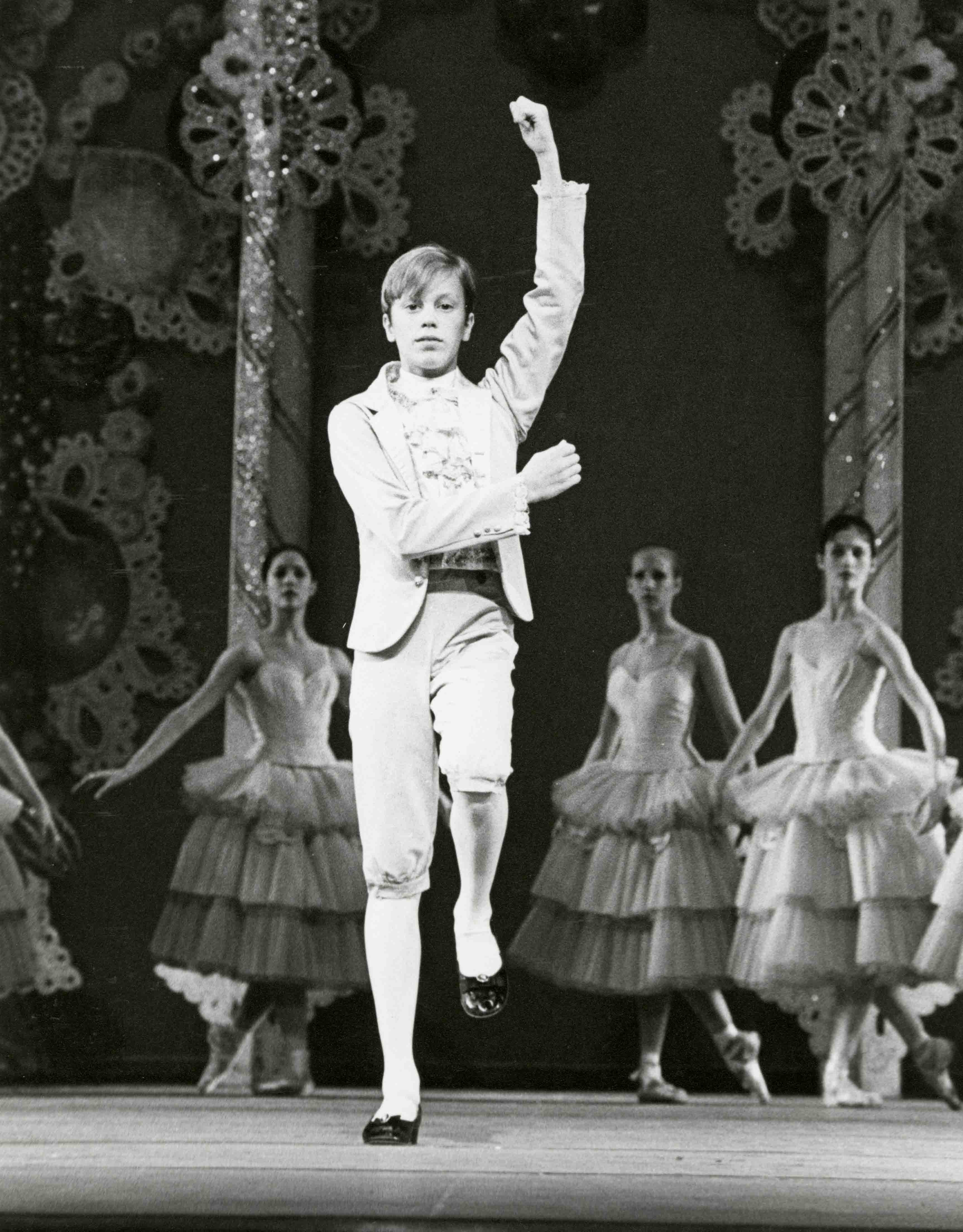

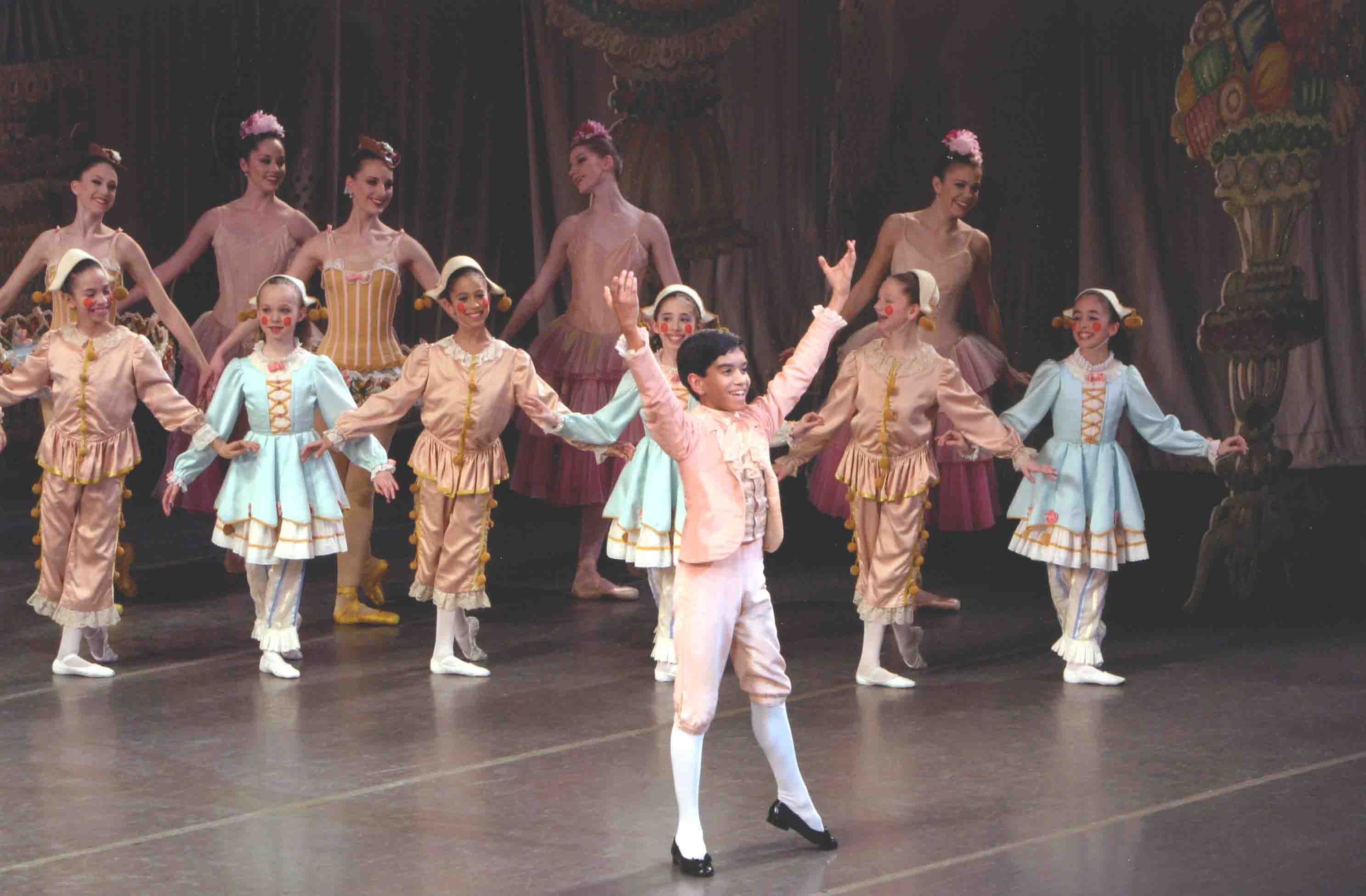

The two characters are distinctly different in kind. The Sugarplum Fairy has been played most touchingly by Balanchine’s ballerinas as tender, even motherly, to her “children.” When we see her first, at the beginning of Act II, she marshals a bevy of diminutive Angels (the youngest and most petite of SAB’s little girls), grave and often visibly nervous as they stream diagonally across the stage in intersecting lines, their tiny feet invisible underneath their gleaming white hoop skirts, their progress as smooth as poured cream. Soon afterward she’s a child-sensitive host to the young Nutcracker Prince and the friend of his heart, Marie–a pair of courageous and exquisitely mannered children whom she has the grace to treat as if they were grown-ups.

Dewdrop is not really human at all, but abstract, or perhaps metaphoric. Brilliant as a faceted diamond, she tears through space and her network of Flowers–a virtuosa amidst the flurry of pink petals suggested by the corps women’s costumes. The greatest Dewdrops I’ve seen were Heather Watts and Karin von Aroldingen, because somehow–only Terpsichore knows how–they gave the role a streak of the tragic. Their interpretation implied that a dewdrop, its shimmering life limited to a mere hour or two, was very much like dancing: dazzling, evocative, wondrous to be sure, but utterly ephemeral.

Mearns’s Dewdrop was probably less rich and less relaxed than it promises to be a few years from now; she still has the air of a stranger to the role or, more accurately, an explorer or an investigator of it. Nevertheless it made me notice an aspect of her dancing I’d so far ignored.

Justly beloved by audiences at large, Mearns is the opposite of the so-called “Balanchine type”: elongated, super-slender, and precise, every step hitting its mark. Mearns is generously proportioned, like Titian’s luxurious nudes, and she extends her body into space with a matching generosity, even though doing so regularly challenges the vertical posture so important to ballet. As Dewdrop, she did all this with her upper body, and produced her familiar sensuous results, not once, it should be noted, allowing her natural amplitude to distort the music’s timing. Her City Ballet predecessors in this kind of dancing have been rare, though memorable–Jillana, Stephanie Saland, and Balanchine’s most potent muse, Suzanne Farrell.

Meanwhile, Mearns’s legs and feet were telling a very different story. Her turns and swift footwork were airy, light, sharp–and plumb-line vertical. She was able to produce this quality at high pressure too. As her dance amidst her attendant Flowers progressed, she sped along the path they repeatedly opened to her with growing authority, excitement, and daring. The contrast between the two modes–lush and crystalline–was a show in itself. Born a natural dancer, Mearns has become a thinking one as well. This bodes well for her future.

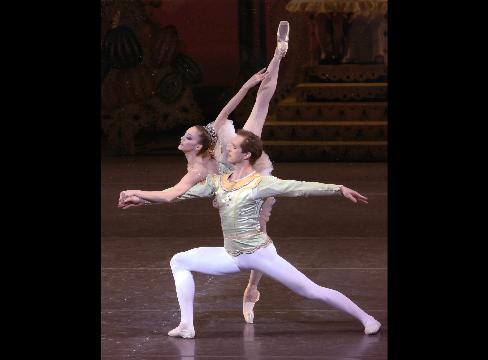

Wand in Hand: Mearns as the Sugarplum Fairy

Photo: Paul Kolnik

As interpreted by Mearns, the Sugarplum Fairy is a benevolent monarch, putting both the inhabitants of her realm and unexpected visitors (or were the children actually destined to come?) on a comfortable footing with her. We see her first early in Act II, bending slightly forward from the waist to greet the tiny gliding Angels (thereby emphasizing their delicious minuteness), waving them into motion with her wand, then finding a place in their dance, making them the framework for her very existence.

In her solo, to the otherworldly music of the celesta, Mearns traced the filigreed patterns of the choreography with delicate footwork, letting that ethereal quality permeate her body until she seemed to be made entirely of spun sugar.

Next she introduced the groups who would perform the divertissement dances–not as if they were subordinates or, worse, slaves trotted out to provide “entertainment,” but as beloved and distinct social enclaves within her realm. Several of the groups represent a foreign, often exotic, clime: China (Tea), for example, Arabia (Coffee), Spain (sweetened chocolate). Obviously Sugarplum is pro-active when it comes to immigration.

When the little Prince arrived with Marie, Mearns’s Sugarplum reacted with surprise, wonder, and concern as the boy related–in a mimed monologue Balanchine performed as a Maryinsky pupil in Russia–the sequence of events that led the youngsters to the “Land of Sweets.” When the account was complete, Mearns sighed with relief and rejoicing, sweeping her arms upward and drawing a long breath that filled her torso.

Cavalier in Attendance: Mearns as the Sugarplum Fairy, with Charles Askegard

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Cut to the grand pas de deux, where Mearns looked as if she were dancing in a cloud of her own perfume, letting her Cavalier be anonymous as, of course, Balanchine designed him to be. He’s there simply to support the woman–in balances, in multiple pirouettes, into the air–so that she can display the full range of her allure.

Remember, Balanchine’s the choreographer who declared “ballet is woman” and frequently said that his function as a choreographer was to serve her.

Mearns made everything in this duet soft, secure, easy–as if were occurring in the dream of a woman focusing on the sensations of her own being. Towards the finish line of this remarkable variation on the theme of lovers’ meeting, Mearns circled the stage in a wide chain of turns until she called to mind a race car speeding up to a wild and dangerous–potentially fatal–pace. This was typical of Mearns’s raw, caution-to-the-winds magnificence, which was one of the first things we knew about her.

Now we know more.

The New York City Ballet will be performing George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC, through January 2, 2011.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

The Nutcracker, in George Balanchine’s (for me) definitive version, danced by the New York City Ballet, opens November 28 at the New York State Theater for a run of six weeks. I know it well, not just as a dance critic but also as a one-time ballet mother whose School of American Ballet-attending child was for several years a member of the show’s huge cast of kids.

The Nutcracker, in George Balanchine’s (for me) definitive version, danced by the New York City Ballet, opens November 28 at the New York State Theater for a run of six weeks. I know it well, not just as a dance critic but also as a one-time ballet mother whose School of American Ballet-attending child was for several years a member of the show’s huge cast of kids.

![IMG_5744[1].jpg](http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/IMG_5744%5B1%5D.jpg)