As E.B. White’s famous mouse observed, “There are always so many worth-while things going on in New York at night.” Beginning OCT 25, I’ll be in a different theater every night for nearly a week and still miss performances I consider must-sees. I plan to write a brief review of each event that will post shortly after its performance. I won’t have time to send the usual e-alert on each posting to my subscribers, but hope all my readers will have a look at SEEING THINGS on a daily basis, starting OCT 26.

The Farrell Dilemma

Suzanne Farrell Ballet / Joyce Theater, NYC / October 19-23, 2011

The Suzanne Farrell Ballet, named for the transcendent dancer who was George Balanchine’s last muse, celebrates its 10th anniversary this year. Ironically, after a decade of generously favorable response to the group’s work, some observers are questioning the wisdom of the enterprise’s very existence.

Sarah Kaufman, the Washington Post’s Pulitzer Prize-winning dance critic, sums up the situation clearly in her review of the troupe’s showing at Kennedy Center in DC (the Farrell Ballet’s official home), which directly preceded the present New York run. The Center’s support for what became the Farrell Ballet had been urged by James Wolfensohn when he was chairman of the Center’s board. Like so many of us, he had been inspired by the ballerina’s incomparable dancing.

Thanks to Farrell’s unique experience with Balanchine and her own vision and skill, the company she evolved over the past decade has consistently offered passages of sensitive, selfless, profoundly musical dancing. Nevertheless, it remains essentially a small pick-up group that can work only sporadically with Farrell. Inevitably, few if any of its dancers have been of the highest professional caliber. Under these circumstances, which are dictated by well-intentioned yet insufficient funding–and the absence of a Lincoln Kirstein clone to guide its growth–the organization can’t hope to develop even as far as an aspiring regional ballet. “The questions now are,” Kaufman concludes, “Could Farrell’s talents be better used? And could [Kennedy Center’s] money be better spent?”

Once it was clear that the New York City Ballet, under Peter Martins, didn’t care to have Farrell around in her ideal role–coaching the dancers in the Balanchine repertory–I once hoped another sort of plan might work. What if three companies ripe for and worthy of what she can offer–Miami City Ballet, just for example–each agreed to hire her for a residency of three months per year, during which time she would coach and teach company class, imparting her deep understanding of Balanchine’s principles? This was a pipe dream, my colleagues insisted; logistics alone would make it impossible and the present state of the economy would make it unlikely.

So dance fans are left with what Farrell can do with the resources she has. What I saw on the opening night of her company’s New York run was disheartening. The ballets performed were Haieff Divertimento (1944), which Farrell had reconstructed; the pas de deux from Diamonds (1967), in which she originated the ballerina role and hasn’t been equaled yet; Meditation (1963), the first ballet Balanchine created for her; and the justly renowned Agon (1957).

As a curtain raiser–a meet-and-greet affair, introducing the dancers to the audience–the light-weight Haieff Divertimento would have been just fine if only Farrell’s dancers had the ability to toss it off with ease technically and the principals had invested in it dramatically.

The work for the four-couple corps and a central, unpartnered man is dotted with spiffy little bows from one dancer to another and from the dancers to the audience. You see immediately that this is the work of Balanchine because of the swift, crisp footwork, the inventiveness in the use of formal classical steps, and the liveliness and logic of the stage patterning. All of this reminded me of the perkier sections of the more substantial, and equally arch Danses Concertantes (1944; revised 1972).

And then, at the heart of the piece, we get the Romantic Balanchine. The man who lacked a partner meets the one destiny has chosen for him. He yearns to possess this sylph or muse who, as women of her ilk do, keeps floating away from him. The best that can be said for the Farrell crew’s execution of the choreography is that Kirk Henning was promising as the main guy and everyone tried really hard to bring it off. The problem here–and throughout the program–is that effort is just what you don’t want to see in a performance.

The pas de deux from Diamonds, the concluding section of the three-part Jewels, revealed most clearly what Farrell has been able to accomplish with her dancers and why the deck is stacked against her. Balanchine created the ballerina role on her and her dancing persona. Her grandeur, her lushness, her daring, and her potent dance imagination are incorporated into its design.

As in every ballet Farrell has mounted on her company, her coaching has clearly been superb and miraculously without ego. But she is working with people (here Violeta Angelova, partnered by Momchil Mladenov) who are dancing the coaching, phrase by phrase, step by step, as if they had a microchip containing Farrell’s wise, detailed, and objective instructions embedded in their bodies. The dancers operate as if they understand these instructions and respect them but they can’t follow them–or, when they do–can’t make them cohere. The results include missteps, disjointedness, and a woeful absence of confidence and spontaneity.

Agon was all too obviously beyond the technical abilities of Farrell’s dancers, and yet its timing was, in every detail, as deliberately strange and adept in its relationship to Stravinsky’s spare, compelling score as it had been at the ballet’s premiere. I remember being one of the astonished witnesses of that first night, merely a teenager but able to recognize that Agon was what the City Ballet was “about.”

The ballerina role in the climactic pas de deux was created on Diana Adams (partnered by Arthur Mitchell). Farrell later inherited the part and now has assigned it to Elisabeth Holowchuk, who performed leading roles in three of the four ballets on the Joyce program. Holowchuk is an accurate dancer but, lacking both inherent drama and sensuousness, she simply doesn’t register as a theatrical personality.

The most relaxed dancing on the Joyce program came with Meditation, made for Farrell when she was still in her teens. It’s a duet that’s a man’s (Everyman’s? The choreographer’s?) naked confession of love for the dream woman he can never fully possess. It registers as a powerful rush of emotion (the Tchaikovsky score helps a lot), leaving little memory of specific steps and or stage patterning. Performing it, Holowchuk managed to entertain the possibility of expressiveness while Michael Cook was convincing through his authenticity and mercifully unpoetic. Any guy could find himself in this situation, he suggested. And this is certainly true–if only because unanswered love can be as emotionally gratifying as love fulfilled.

Shoring up the sporadic performances of her troupe, Farrell has contrived projects that are supposedly do-gooders for the dance community. Borrowing dancers from other companies to fill out the ranks of her necessarily small troupe is claimed to enlarge the visiting dancers’ opportunities. Does importing more proficient dancers than she has to lead a production fall into the same category? Or is it evidence that the Farrell Ballet is not in a position to produce stars from its own ranks?

Another undertaking, reviving Balanchine works previously thought to be lost, presumably rescues them from oblivion. But Balanchine, an undeniably productive and resourceful choreographer, himself allowed these works to disappear. Often he recycled the best inventions in them when he made a new ballet. In viewing Farrell’s reconstitution of the “lost” works, Balanchine fans with long memories can enjoy the parlor game of seeing where some phrases or effects showed up in subsequent ballets–reworked, refined, and elaborated in their new context.

Farrell’s projects, especially when given formal names like the Artistic Partner program and the Balanchine Preservation Initiative, may engender respect for her company and elicit significant funding. But they are, in the end, essentially social work and scholarly endeavor, not art.

Farrell’s dancing was an immense gift to the world. People who never had the chance to see it “live” fall in love with it via video alone. Once a ballerina who couldn’t be surpassed, Farrell subsequently demonstrated her extraordinary ability as a teacher and coach of Balanchine’s style and repertory. Surely she’s earned the opportunity to function at a level that corresponds to her gifts.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Don’t Go Near the Water

New York City Ballet: Ocean’s Kingdom / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / September 22, 24, 25, 27, 29

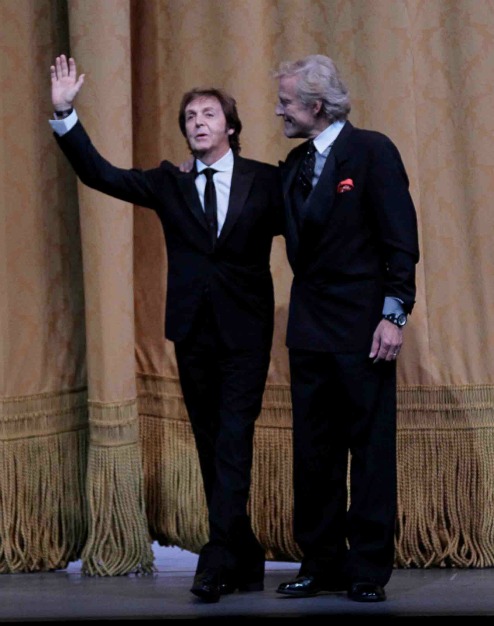

Much touted in advance, New York City Ballet’s just-premiered $800,000 Ocean’s Kingdom is a once-in-a-lifetime (please, god) collaboration by Paul McCartney (first a Beatle, now a knight) and Peter Martins (first a superb dancer, now a company director, a choreographer, and a Danish knight to boot).

Pas de Deux No. 1: Paul McCartney and Peter Martins, creators of Ocean’s Kingdom for New York City Ballet

Photo: Paul Kolnik

On the side of Good in the new ballet is an undersea population devoted to peace and love, featuring Princess Honorata (Sara Mearns). Representing the Bad–aggression, abduction, violence, and threatening hair-do’s–are the invading terrestrials, among whom the only nice guy is Prince Stone (Robert Fairchild). He falls in instant, Romeo & Juliet-style love with the Princess, and of course she, requiring a shade more persuasion, with him. But his nasty elder brother, King Terra (who plagued these characters with their names?) wants this trophy naiad for himself.

Pas de Deux No. 2: Sara Mearns and Robert Fairchild, heroine and hero of Ocean’s Kingdom

Photo: Paul Kolnik

When the ballet winds down its 55-minute reign, it ends happily, without for one moment having earned the right to call itself a fairytale, its dramatic and emotional range being picayune. Real fairy tales–a powerful literary genre–take good and evil seriously and enact them with force. Observe any kid in their thrall.

When it comes to classical-music credits on his résumé, McCartney’s been there and done that for nearly a decade. Nevertheless, his score for Ocean runs the gamut from movie music to faux-Broadway. The fashion designer Stella McCartney, daughter to Sir Paul, did the costumes, which range from limply imagined blue tunics for the ladies from the sea to gaudy tattooed cat suits for “The Baddies,” as the composer deftly nicknamed them. The scenery, for which the program blames Perry Silvey, is weightless, almost non-existent, consisting of unconvincing projections. Does the feeble decor reflect City Ballet’s making a last-ditch gesture toward keeping expenses down just in case the ballet fails to prove immortal?

The pre-curtain efforts of the City Ballet’s chief music man Fayçal Karoui and his orchestra to make a case for the score were well brought off but unconvincing. The little teaching session served to fill in time because, I’m told, McCartney refused to have any other ballet share the gala opening-night program, (not even Balanchine’s Union Jack, which was originally scheduled).

“Baddies”: Amar Ramasar (in black tights) heading up the gang of villains in Ocean’s Kingdom

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The choreography is instantly forgettable. Even the magnificent Sara Mearns offers merely a stymied sampling of the gifts that make her one of the most riveting dancers of our time. Instead of using her full-bodied emotional power, for example, she just acts with her face, now sweetly in love (Sara Mearns? Sweetly?), now vapidly sorrowful. Her suitor, Robert Fairchild, looks benumbed by the choreographic vacuity and seems to be doing nothing beyond what he’s been told to do. This is hardly the dancer–ardent, witty, alive to every event–who last year originated the hero role in the City Ballet’s far-better venture into the waves, Alexei Ratmansky’s Namouna.

The couple have the requisite love duets in which Mearns fleetingly recalled her fluent, sensuous, and imaginative self–and one duet that briefly suggests apache dance. Yet not a single phrase that Martins choreographed for the pair is likely to be remembered once the curtain falls.

Dark Angel: Georgina Pazcoguin (r.) in Ocean’s Kingdom

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The only distinguished dancing in the show came from the veteran corps dancer Georgina Pazcoguin, in the role of Scala, a handmaiden of Honorata who, for reasons negligently kept secret, first betrays her mistress and the lady’s suitor, then saves their lives, sacrificing her own on their behalf.

Pazcoguin stood out among the more than 45 dancers trapped in Ocean by following her usual method of building a full persona for her character. In her starkly cut black gown she looked like a Graham dancer from days of yore, the confidante who tries to warn the heroine that the situation is dire. Needless to say, this approach didn’t fit in stylistically with anything else going on, but, for me, it was the only meaningful action on stage. Pazcoguin should have been made a soloist long ago.

For some reason, there’s a grand party–to pep things up with some acrobatic, exotic, and comic dancing, perhaps–but its raison d’être, plot-wise, is obscure. It features Daniel Ulbricht, the company’s expert in the acrobatic mode. He shines far more, however, when he’s used as a regular dancer, not a freak, or when the antics of a jester are part of the character he’s dancing.

Would I recommend this product to a friend, as the Internet so often inquires? Rhetorical question. No need for a reply.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Bournonville Remembers

To the reader:

The essay below, on the ballet school scene from August Bournonville’s Konservatoriet (The Conservatory), was commissioned by the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, Denmark. It first appeared, translated into Danish by Lise Kaiser, in the Royal Danish Ballet’s illustrated program in Spring 2011. The original English version appears here for the first time with the gracious permission of the Royal Theatre.

August Bournonville (1805-1879)–dancer and choreographer, instructor and artistic director–gave the Royal Danish Ballet a repertory and a dancing style that have made it, and kept it, a world-class phenomenon. As his voluminous memoir, Mit Teaterliv (My Theatre Life), reveals, several of his ballets that are alive in the repertory today were inspired by his personal experience. Konservatoriet (The Conservatory), created in 1849, is one of them.

Charles Andersen (in flight) and Jean-Lucien Massot (r.) as the ballet master in the Royal Danish Ballet’s production of August Bournonville’s Konservatoriet

Photo: Costin Radu

Bournonville was trained for a career in ballet from childhood–at Copenhagen’s Royal Theatre, where his father, Antoine, was ballet master (that is, artistic director). In the 1820s, to put the finishing touch on his skills, he traveled to Paris, then the dance capital of the world. There he studied with the celebrated Auguste Vestris, who came to be known as le dieu de la danse (god of the dance). Eventually, through his talent and diligence, the young Bournonville progressed to performing with the Paris Opera Ballet, even partnering the most celebrated ballerina of the Romantic age, Marie Taglioni.

Diana Cuni in flight in Konservatoriet

Photo: Costin Radu

After distinguishing himself abroad, Bournonville returned to Denmark to rescue the Royal Danish Ballet from an arid period and to rejuvenate it. But through a long career as ballet master in Copenhagen, he never forgot his experience in Paris. Some two decades after his return home, just after he retired from performing, he immortalized in Konservatoriet his memory of the classroom of those early days. Music–both borrowed and composed–by Holger Simon Paulli evoked the scene, as did the women’s filmy white tutus, emblems of Romantic-era dancing.

The setting of Konservatoriet is one common to ballet studios everywhere–an uncluttered space. In today’s renditions, the scenic design omits even the ornate pictures on the walls in the original version. Now only a single decorative element signals the grandeur of Parisian ballet–a crystal chandelier, albeit one that’s swathed in gauzy fabric to keep off the dust during the day, when the theater’s routine work takes place.

(L. to r.) Charles Andersen, Gregory Dean, and Alexander Staeger, with pupils of the Royal Danish Ballet’s school behind them, in Konservatoriet

Photo: Costin Radu

The studio is peopled by a ballet master who directs the daily class and dances as well; a bevy of freshly minted adult dancers, two of the women obviously favorites–by virtue of their talent and charm; a handful of children who are being trained for the stage by taking class alongside their role models; and a violinist to accompany them all in their exertions.

The choreography Bournonville devised for these characters has an architecture that is impeccably ordered, varied, and balanced. Viewers may absorb this great virtue only subliminally because of the vitality and beauty of what is right before their eyes: the duets and trios, the solos that sometimes hint at a particular personal quality, and the small groups that sweep across the floor one after the other, as if they were impelled by the dancers’ camaraderie. And of course the children have their little moment in the sun. Audiences are invariably enchanted by the immature bodies’ precocious technical aplomb.

Children of the Royal Danish Ballet’s school with Nicolai Hansen as the ballet master in Konservatoriet

Photo: Costin Radu

Bournonville’s deftness in turning the commonplace practices of the classroom into theatrically fascinating material is everywhere apparent. Example: The ballet master summons first one of his protégées (demonstrating that he wants her to begin with the backbend phrase of a sequence he has no doubt taught her), then the other. The two proceed to execute the same bit of choreography, but with the second woman a phrase behind the first. So, when a leg is extended hip-high by one and then the other, both women turning in place, the pair creates the hypnotic effect of a pair of windshield wipers gone out of synch. As if by magic–you can’t catch how it’s done–they end by working in unison.

Thomas Lund, flanked by Gitte Lindstrøm (l.) and Gudrun Bojesen (r.) in Konservatoriet

Photo: Martin Mydtskov Rønne

At the heart of the work is a dance for three–the ballet master and the two “special” young women, who fleetingly hint both at sweet sisterhood and competitive rivalry. Its various solos, duets, and trios are connected so naturally they look joined by happenstance–or, more likely, inevitability.

One of the many marvels in the ballet school scene is its opening. It’s no accident that Konservatoriet begins and ends with the same basic step–a grand plié–that a dancer does, many times over, every day of his or her dancing life. It makes for stretch and suppleness and, done without support as it is here, is a challenging test of balance. The curtain rises on a view of the performers neatly aligned in rows, facing the audience. In unison, they take one step forward, then–legs and feet “turned out” so that their kneecaps face opposite sides of the stage–bend their knees and smoothly, torso erect, head exquisitely poised, lower their bodies towards the floor. And, still without a tremor, rise again.

The ballet finishes with the same action, this time adding a single flourish–the sudden flaring of one leg into a curved position behind the body while the opposite arm is raised in a complementary arc. The pose recalls statues by the Renaissance sculptor Giovanni da Bologna that inspired the use in ballet of this sublimely balanced position. The figure represents Mercury, messenger of the gods.

Susanne Grinder (l.) and Kizzy Matiakis (r.) as the prize young women of their class in Konservatoriet

Photo: Costin Radu

Konservatoriet is danced in the unique style that Bournonville developed for his dancers. To this day there has been no classical dance company in the world that can equal the Royal Danish Ballet in its specialties.

Notice, for instance, the way these dancers look when they travel horizontally through the air. Their leaps don’t take the swift, straight path of an arrow or bullet; rather, they’re buoyant, like feathers blown by an April breeze.

Notice, too, the quick, crisp footwork. On the women it looks positively filigreed. Wherever possible, jumps are festooned with beats of one foot against the other, executed immaculately and at hummingbird speed. Viewers keeping close watch will marvel at the fact that, on the landings, just for a split second, the turned-out feet snap shut–right heel against left toes, left heel against right toes–as uncompromisingly predatory as a shark’s jaws, the exactitude and energy of that action helping the dancer rebound into the air.

Above the waist the head, neck, and shoulders continuously shift position, gently, to complement the formidable work of the legs and feet. The torso is pliant but calm; the arms, often held low and still.

Bournonville’s choreography requires dancers who, within even a brief passage, can alternate slow and fast movement, perform difficult steps with equal panache to both right and left, and spring into any direction at all without the slightest hint beforehand of which way that will be.

Dancers often say that Bournonville style demands a killer technique, especially because the performer must behave as if everything were perfectly easy. What’s more, the choreography must be offered to the audience with a friendly, modest demeanor in which there’s not a single thing that’s fake. And whatever group is on the stage at a given time, all its members must present themselves as part of a heartfelt community. To dance according to Bournonville’s values is to create a metaphor for civilized conduct.

The Konservatoriet we know today was not, at first, a stand-alone ballet. As its original title indicated, it was longer–Konservatoriet, eller Et Avis Frieri (The Conservatory, or A Proposal of Marriage Through the Newspaper). A lightweight but appealing plot, bubbling with gaiety and requiring eloquent mime, was wrapped around the ballet class scene.

Monsieur Dufour, a late-middle-aged, bumbling yet self-congratulatory administrator of the leading ballet academy in Paris, has half-promised to marry his faithful housekeeper. Nevertheless hoping for a more glamorous match, he places an advertisement in a newspaper personals column. Seeing this, the academy’s students inveigle him into an evening at a restaurant with an outdoor space for dancing, a peaceable view of nature, and a huge and varied clientele. There, amidst much fun his expense, Dufour learns to accept reality.

The very young Kirsten Ralov as the aspiring child, Fanny, flanked by Else Højgaard (l.) and Margot Lander (r.) as the budding ballerinas who befriend her

Photo: Huset Mydtskov, 1933

Meanwhile little Fanny, the daughter of impoverished street musicians, longs to get the serious dance training her native talent deserves but is turned down by Dufour because she can’t pay for lessons. The academy’s two budding ballerinas “adopt” her cause and see to it that her future is assured.

By the mid-1930s, the time of the full-length Konservatoriet had come and gone; in 1941 the ballet class segment began to be performed independently. In 1995 the complete version was revived by a trio of seasoned Bournonville experts that included Kirsten Ralov–a Royal Ballet stalwart as dancer, instructor, and administrator–who had danced the role of Fanny as a child. While the revival had its charm–and, certainly, historical interest–it didn’t appeal to today’s audience. However, the classroom scene continues to thrive, describing with affection what ballet was like in early-nineteenth-century Paris.

Konservatoriet offers far more than nostalgia, though. It indicates how Bournonville absorbed the crystalline precision of the French style of dancing and quietly adapted it to the humane values of Danish culture. Even so, he was not merely adept. It was his unique genius–inborn, rare, impossible to explain but easy to recognize–that allowed him to create this gleaming ballet about classical ballet, which reveals the very foundations of the art.

Tobi Tobias writes a weekly column on dance, SEEING THINGS, for ArtsJournal (www.artsjournal.com/tobias). For her work on Bournonville and the Royal Danish Ballet, she was honored with a Danish knighthood.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Fox Tale

Mark Morris Dance Group / Rose Theater, Lincoln Center / August 18-20, 2011

Who does Mark Morris think he is, Bronislava Nijinska? George Balanchine? These superlative choreographers are among the several who preceded him in providing the choreography for Igor Stravinsky’s foxy music-and-dance entertainment, Renard. Nijinska was the first to do so, in 1922, for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Balanchine choreographed the first American production in 1947 for Ballet Society, a forerunner of New York City Ballet. Last week Morris brought his own version, recently premiered at Tanglewood, to the annual Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center.

Who’s Who: Members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris’s version of Stravinsky’s Renard: (l. to r.) Dallas McMurray, Laurel Lynch, William Smith III, Jenn Weddel, Aaron Loux, Rita Donohue, Domingo Estrada Jr.

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Stravinsky based his jaunty opera-ballet on a Russian folk tale and French stories that stem from the Middle Ages. It gives a simple account of a barnyard trickster, Fox, who is typically out to capture Cock for his dinner. Cat and Goat come to their poultry pal’s rescue–twice. After the second round they prevent a third by offing the villain. Of course Fox is resurrected as the ballet closes; evil is irrepressible.

In Morris’s version the piece has seven dancers enthusiastically covering the original’s cohort of “clowns, dancers, and acrobats.” In the pit are four singers–two tenors, one baritone, and a bass–along with the Mark Morris Dance Group Music Ensemble, conducted by Stefan Asbury. The exuberant score, composed in 1916, derives from a rich mix of musical traditions ranging from folk to classical. It has a colorful, rough-hewn instrumentation featuring the cimbalom, a stringed instrument played with mallets.

The composer wrote his own libretto, which–apart from a couple of cheerfully lewd moments–would make a great comic book for the very young. (No doubt Renard‘s designer, Maira Kalman, has already thought of this). The piece is also said to retain a hint of satire, aimed at the clergy and aristocracy. That’s hard to see today but, as in Æsop and La Fontaine, the “characters” are all animals because that has proved to be a safe device for exhibiting a spectrum of human foibles.

The Princess Edmond de Polignac (daughter of Isaac Singer, who made his fortune with the sewing machine), commissioned the score from Stravinsky for her salon. Hence, perhaps, its brevity; the piece is about 15 minutes long. Instead, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes co-opted it, staging it in Paris in 1922, with Bronislava (Les Noces) Nijinska providing the choreography. Serge Lifar choreographed the company’s revival of the piece in 1929. And so on. What enticed Morris to try his hand? As so often happens, I assume, the music made him. And, as he told Robert Johnson, of the Star-Ledger, he finds Renard “interesting because of the folk references: the folk theater, and the clowning, and the tragedy.”

A Game of Cock and Fox: Aaron Loux (peering) and Dallas McMurray (hiding) in Morris’s Renard

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The value of Morris’s version lies largely in its apt and amusing details. There’s little of the stuff we call choreography to ogle, but each of the animals gratifyingly moves according to its species. (You don’t have to read their t-shirts, which spell out their names in a divided way, to identify them.) Cock sits atop his fence radiating self-importance (though dissolving into self-pity with quotes from The Dying Swan when the sneakily prowling Fox attacks him). Being birds of very little brain, the three Hens (Morris’s addition to the romp) work as an indivisible trio, pecking at any available grain and flustered by every event. As for Cat, he is simply adorable, velvety in every pawfall.

I was especially fond of the quotes from Martha Graham, which Morris doesn’t usually indulge in. Fox replicates the scuttle in kneeling position that Graham often used to indicate pleading, and the doing in of that wily fellow parodies the murder of Agamemnon in Clytemnestra. Armed with a gargantuan butcher’s knife and a hangman’s rope, Cat and Goat move their victim out of sight, as is the custom in classical Greek drama. While the “fatal” assault is taking place behind the picket fence, it’s indicated by blood red streamers rippling frantically from the talons of the Hens.

The set and costumes were provided by Maira Kalman, author-illustrator of two blogs for the New York Times and, better yet, a series of brilliantly drawn-in-paint and whimsically written books for kids. (See the end papers of Ooh-la-la [Max in Love], which feature sketches of the Ballets Russes era, including portraits of, I believe, Stravinsky and Balanchine.)

For Renard, Kalman designed a simple set of home bases for the characters (a tactic Noguchi used for Graham). Center stage is a picket fence with disappearing peepholes, which rotates to reveal how Cock manages to sit atop it and serves as a hideout when mayhem threatens. The bright, cheery costumes look like mid-twentieth-century threads for gung-ho teens, with ears and tails as appropriate.

While Renard is merely a bagatelle, the balance of the program was devoted to a pair of recent Morris masterworks, Socrates and Festival Dance, which I wrote about here and here.

Emblems of Dancing: Aaron Loux and Rita Donohue in Morris’s Festival Dance

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Even if your life seems to be full of sly foxes (and/or cunning vixens), I’m sure Festival Dance would improve your outlook. Set to a piano trio by Johann Nepomuk Hummel that cries out to be danced, its ingenious use of stage patterns (advanced math in motion) never once distracts your attention from the tender love between the leading couple, Laurel Lynch and William Smith III, and the community of six pairs to which they belong. The bond between personal and communal love is one of Morris’s perennial themes and the piece expresses it touchingly.

Heart to Heart: (center) Laurel Lynch and William Smith III in Morris’s Festival Dance

Photo: Stephanie Berger

While Festival Dance is entirely accessible, Socrates is a profoundly subtle dance that, accompanied by Satie’s reticent, haunting music of the same name, takes you into the philosopher’s world and mindset. Watching the dancers represent the situation with movement that unites the sober grace of Greek statuary and literal gesture, the susceptible viewer is gradually led into experiencing Socrates’ calm, courageous death just as the dancers portray it: as his or her own.

Bound Together: Members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris’s Socrates

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Nothing is dramatized in this process, you understand. It has nothing to do with acting and everything to do with action. The performers’ attitude is completely neutral. Throughout the piece, by turns, each of the dancers has appeared to be the pivotal character for a fleeting moment. At the close of the piece, every one of them is Socrates. Fifteen bodies lie supine, filling the stage in orderly lines, finally bereft of the motion that made them eloquent, And the empathic spectator is no longer a looker-on but one of their number.

Note: Jacques-Louis David’s 1787 painting The Death of Socrates was part of the inspiration for Morris’s choreography and indeed provided the palette for Martin Pakledinaz’s beautifully understated Grecian-style costumes. The picture is in the permanent collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. To discover more of Maira Kalman’s work, go here.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Interim Report

Dear Readers,

My next posting on SEEING THINGS will cover the NYC premiere of Mark Morris’s new Renard (to Stravinsky’s score for a small-scale opera-ballet) at the David H. Kohn Theatre, Lincoln Center, August 18-20. The performances are part of the Mostly Mozart Festival.

The program will include two other Morris works, which I’ve written about earlier, Socrates and Festival Dance.

After Labor Day, as the fall season gets underway, I’ll resume more frequent posting.

Best,

tt

Russian Unorthodox

Mariinsky Ballet / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 11 – 16, 2011

A Is for Arabesque: The Mariinsky Ballet’s Yekaterina Kondaurova in the title role of Alexei Ratmansky’s Anna Karenina

Photo: Natasha Razina

When New York’s dance fans heard “The Russians are coming, the Russians are coming!” they were duly aroused to fever pitch by the news. As part of this summer’s Lincoln Center Festival, the Mariinsky Ballet (having officially gone back to its birth name) arrived at the Metropolitan Opera House for a week. From July 11 through 16, it rotated three programs that–surprise!–didn’t have a swan, a wili, or a beautiful dreamer in sight.

The company brought its own orchestra as well as Valery Gergiev, the celebrated conductor who is also the artistic director and general director of the Mariinsky Theatre. The vibrant sound and fervor Gergiev drew from his musicians put our best known local ballet maestros to shame. His taste in composers, however, is questionable. Gergiev was having a field day celebrating the work of one of his long-time favorites, Rodion Shchedrin.

Opening night was devoted to Alexei Ratmansky’s Anna Karenina, created for the Royal Danish Ballet in 2004. The ballet was, quite simply, a flop, despite its inventive Mikael Melbye décor and the admirable efforts of the dancers. When the curtain fell and it was time for American dance enthusiasts to rise, applauding and bravo-ing madly–well, in my countless visits to the Met, I have never witnessed such a tepid response.

What’s wrong with this ballet? Well, for one thing, it doesn’t have much of a relationship to Tolstoy’s novel. It blithely ignores setting off the doom-eager adulterous relationship between Anna and Vronsky with the quiet domestic contentment achieved by Kitty and Levin. Taken together, the two pairs make a profound statement about human nature; Anna and Vronsky alone encourages melodrama.

Heartbreak House: Anna Karenina with Diana Vishneva (as Anna) in the arms of Yuri Smekalov (as Vronsky)

Photo: Stephanie Berger

What’s more, the piercing detail with which a character’s inner life is explored in the novel finds no equivalent in Ratmansky’s choreography. (Given the rich and complex work this choreographer has produced in recent years, I suspect he could do a better job on the material today.)

Worse still, even if you’re willing to forget about Tolstoy, the ballet doesn’t offer the satisfaction of watching a heady illicit romance come to the grief for which it’s clearly destined. The choreography keeps on making gestures toward feeling–setting you up, as it were–but it’s always so fragmented that nothing peaks or resolves. Just when you assume the ballet is about to deliver a solo, duet, or trio for Anna, Vronsky, and Anna’s husband (the father of the child that is Anna’s strongest link with domesticity), things begin and then abruptly break off, as if the muse had come to the choreographer on union time.

The dancers did their best under the unfavorable circumstances. Typically, Diana Vishneva’s Anna was thoughtfully constructed to convey the heroine’s driving emotions–here erotic passion, anguished indecision, and despair. If Vishneva didn’t quite own these emotions, the Mariinsky’s current stylistic preferences hardly encourage her to do so. As Vronsky, Yuri Smekalov, substituting at the last moment for Vishneva’s usual partner in the role, did a credible job playing a generic irresistible lover. Islom Baimuradov made an appropriately arid husband, who lives by traditional rules of conduct, unable to deal with events lying beyond these boundaries.

They say that you never leave a show humming the scenery but, given the movie-music nature of the score and the failure of the choreography to offer a rich, fluent narrative, let alone convey emotional depth, the audience is left to admire Mikael Melbye’s décor. Melbye relies heavily on projections onto bare walls to indicate place–from the upper-middle-class lavishness of Anna’s home to the dismal street on which Vronsky lives. Three-dimensional objects are kept to a bare minimum, for example, the child’s toy train (symbolizing, first, the railway accident that coincides with the lovers’ fateful meeting, and then Anna’s suicide) and Karenin’s handsome desk (a safety zone from which he tries to keep control over things that are tragically beyond his grasp).

Melbye’s tour de force is the projection of a dark train moving heavily through a gloomy dusk, headlights glowing, then swiveling to reveal a lighted interior populated with passengers. It prophesizes Anna’s suicide of course, but also plants the idea that the train that will kill Anna will be carrying ordinary people, going about their ordinary lives. This kind of irony is something the choreography could use more of; as we know, irony used in an amusing vein has become a Ratmansky specialty.

You Go, Girl! Viktoria Tereshkina in Alexei Ratmansky’s The Little Humpbacked Horse

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Ratmansky’s The Little Humpbacked Horse, was not only the hit of the Mariinsky’s New York engagement, but quite possibly the hit of the New York dance season. Like this choreographer’s much enjoyed The Bright Stream, recently adopted by American Ballet Theatre, it’s a transforming remake of an old ballet. Like his Namouna, created for New York City Ballet last year, it juxtaposes so many elements of dancing–classical ballet, folk dance, popular dance, traditional mime with some literal additions, quotes from ballets we already know, bits of pedestrian action–expertly weaving them together, that you want to see the show again, right away, so as to fully grasp its delights.

The history of the ballet, neatly compressed in the program note, begins in 1864 with choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon to a score by Cesare Pugni and continues with a revival by Petipa in 1895 and a Petipa-derived version by Gorsky in 1901. In 1960, Alexander Radunsky created his own production, which featured a new score provided by Shchedrin and starred the composer’s wife, the celebrated ballerina Maya Plisetskaya. Ratmansky’s version had its premiere in 2009.

From the first, Horse has been based on a mid-19th century story by Pyotr Yershov, presented in the manner of a folk tale. Every Russian child, apparently, is exposed to it. Only long experience with tweeting could enable a succinct account of the narrative. Here’s the best I can do: Old farmer has three sons, the elder two no better than they should be and the youngest, Ivan, thought to be a fool. (In Russian literature a “fool” is often an inept stripling who hasn’t yet grown up to be a hero.)

Wild horses are ravaging the family’s wheat field. Uninvited, Ivan goes out to cope, catches a mare who gives him a pair of magnificent horses and a puny hunch-backed one in exchange for her freedom. In the course of these events Ivan encounters a flock of Firebirds and comes away with an outsize feather purported to work wonders (think Fokine’s Firebird).

Ivan’s ne’er-do-well brothers steal the fine horses and repair to the town square–where much ebullient activity is carried on (think Petrushka)–to sell them. Ivan repossesses the steeds just in time for the Tsar–a short, puny man of a certain age with a childish sense of entitlement–to commandeer them for himself, in return giving Ivan the powers of his present right-hand-man, the Gentleman of the Bedchamber. Said Gentleman is justly resentful and connives to send Ivan on three impossible errands. (As you knew already, everything in fairy and folk tales comes in threes.)

Task #1 is to seek out the Firebirds in their home at “the outer edge of the world,” where they harbor the Tsar Maiden, whom the Tsar has seen in a vision and yearns to marry. Result: Ivan falls in love with the TM and she with him. Task #2: Back at the palace, the TM staves off the Tsar’s advances by saying she must have a special engagement ring that lies under the sea. Away goes Ivan and gets it, with the help of his magical little horse, a cooperative Princess of the Sea, and a whole underwater community (think Bournonville’s Napoli, Act II, and Ashton’s Ondine). Task #3: The TM informs the Tsar that she can only marry a man who’s young and handsome. One can achieve such a make-over, it seems, through immersion in boiling water. The Gentleman makes Ivan try it first, the little horse casts a temporary spell on the water, and our hero emerges unscathed, still young, more polished, and better dressed. The Tsar goes next and the burning bath conveniently does him in. After the court and general populace indulge in the briefest of mourning periods, Ivan gets his just deserts: the hand of the Tsar Maiden and the tsardom itself.

All’s Well That Ends Well: Vladimir Shklyarov (as Ivan) and Tereshkina (as the Tsar Maiden) in The Little Humpbacked Horse. The white-bearded man just above the pair of water nymphs on the left is Vladimir Ponomarev.

Photo: Stephanie Berger

In a glorious finale everyone in the story returns to the stage, alive, joyous, and the very best of friends.

Despite the whacky, complicated narrative, which is played out with robust enthusiasm, the ballet provides lots of dancing. The virtuosic and lyrical passages, which include a couple of crackerjack pas de deux, are matched with theatricalized folk dances that only Mark Morris could equal. Ratmansky’s dance for an octet of Gypsies is a major proof of how wild, sensuous, and yet communal such a generically trite entry can be. Ensemble dances follow this choreographer’s innovative custom of allowing no formations composed of lines that are straight and evenly spaced, creating an imprisoning grid, but rather letting the lines swoop, curl, or track back on themselves here and there, and having a group of twelve re-form not just into the obvious three fours or four threes but, say, a five and a seven.

Ask a a bunch of Horse enthusiasts to name their favorite section of the ballet and you’ll get widely various answers. Let me tell you mine. It’s the scene in which the wet-nurses (if you’ve got a young kid with you, it’s simpler just to say “nannies”) feed the Tsar and settle him down to sleep. Since he’s childish, the nurses respond with instinctive empathy, tenderly treating him like a child. We’ve met them earlier–a sextet of gentle young women modestly dressed in plain cardigans and longish dark skirts, as innocent as girls who might soon be joining a nunnery. Although they’re radiantly beautiful, they prefer to keep their heads bowed, their eyes downcast. As they tend the Tsar, they cluster and re-cluster. One of them eventually feeds him (with a spoon), as one would feed milky porridge to a baby. To amuse him, they tickle him, then settle him down to sleep, one of them reading him a bedtime story as the others tiptoe away (on pointe, of course). The event is ludicrous, yet the atmosphere is straight out of Goodnight Moon.

Full Fathom Five: Yekaterina Kondaurova as the Queen of the Sea in The Little Humpbacked Horse. The grouping of the underwater community recalls Nijinska’s Les Noces and Balanchine’s Prodigal Son

Photo: Natasha Razina

At their most engaging, Maxim Isayev’s sets–radically pared down and striking–derive from the work of avant-garde Russian artists in the Supremacist and Constructivist movements, Kasimir Malevitch and Alexander Rodchenko, for instance. His costumes are drastically simple, boldly colored, and occasionally plain weird. Example? The undersea folks, male and female alike, are clad in bathing caps and long tulle skirts; each chest is emblazoned with an upside-down image of the owner’s face–that is, the individual’s reflection in the water. Both kids and sophisticated adults with a bent for whimsy will appreciate them mightily.

The dancers seemed to be enjoying themselves to the hilt. Vladimir Shklyarov, the epitome of boyish charm and breathtaking technique, took top honors as Ivan, though his alternate, Alexander Sergeyev, was fine, too; it’s a great role. Alina Somova was delectable as the Tsar Maiden; she got the tone of the character just right–funny and adorable in equal parts, the right tsar’s perfect mate. I must admit that I didn’t care for Victoria Tereshkina in the part. She may be the company’s mistress of steely technique, but when she tried to be goofy she turned into Carol Burnett. Andrei Ivanov was perfect as the Tsar, ridiculously self-involved yet with an undercurrent of pathos. Islom Baimuradov, playing the Gentleman of the Bedchamber, made a villain with a sense of humor. These last two characterizations are prevalent in Ratmansky’s mature work, which is generous and humane. No figure is dismissed by being labeled.

Ratmansky will no doubt work further on this piece, as I understand he will do on his Nutcracker for ABT and has done with Namouna. He may well tie up some of the loose ends and edit flights of fancy that are just too bizarre. He might even improve the ballet by shortening it a bit. If Horse is taken on by ABT, such fixes would be useful, but they’re not imperative. Just as it stands, this ballet generates a helluva lot of happiness.

The single mixed-repertory program in the Mariinsky engagement was as mixed as you can get. The tenuous connection between the two ballets on offer was their being set to music by Bizet. Sort of. Balanchine’s ravishing Symphony in C was wisely content with echt Bizet; Alberto Alonso’s 1967 Carmen Suite, was set to a score by the overly prominent Shchedrin that re-orchestrates parts of Bizet’s ever-popular opera and interpolates excerpts of two other Bizet pieces.

Can You Forgive Her? Yevgeny Ivanchenko in Alberto Alonso’s Carmen Suite, as the Toreador, whom the lady can’t resist

Photo: Stephanie Berger

A matter of red and black ruffles and ruffled passions, Carmen Suite was surely intended to be about sex and death. Yet it turns out to be about female legs as an erotic fetish, a weapon brandished as a means of enticement. The ballet’s prominent motif appears to be stalking, which the music admittedly encourages. Alonso gives us the three familiar main characters–Carmen (a gal who spells trouble) and her two (let’s say) boyfriends, Don José (who loves her truly, despite or because of her tempestuous nature) and the Toreador (who–well, you know how it is). A fourth personage, a woman unitarded in black from the tip of her toes to the top of her skull, was announced by the program to be Fate. I would have guessed Death, but–whatever. The ballet is arranged as a string of vignettes, no doubt intended to hit just the high points of the tale. It uses a paltry vocabulary and is exasperatingly mechanical, almost robotic, besides. As the heroine, Vishneva was fluid, luxuriously slow, only toward the close of the ballet, when Don José stabbed her. Then, dying, she slipped from his arms to the floor, all sensuous flesh.

Bizet à la Russe: Andrian Fadeyev partnering Alina Somova in the first movement of Balanchine’s Symphony in C

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Balanchine’s 1947 Symphony in C–with its sublime second movement and its glorious evidence overall of the range classical ballet can encompass–was the lone traditional work the engagement presented. It came as no surprise that the Russians should dance the piece very differently from the New York City Ballet crew whose predecessors danced it for decades after it was created on the Paris Opera Ballet. The Mariinsky’s production emphasizes delicacy (even in the pastel hues of the costumes), precision, and mastery, rather than the spontaneity and barely contained energy of the New Yorkers. Of course I prefer “our” style, but that may be partly because I grew up with it.

Alina Somova and Andrian Fadeyev led the first movement, she with tremendous fluency and ease (and few of her old show-offy habits), he with clarity and naturalness. Yevgenia Obraztsova was perky and peppy in the third, allegro vivace, movement. Her partner, Vladimir Shklyarov, showed once again why he’s the guy everyone’s been talking about.

Our Object All Sublime: Ulyana Lopatkina partnered by Daniil Korsuntsev in the second movement of Symphony in C

Photo: Stephanie Berger

What counts most, though, in Symphony in C is the second movement. The Mariinsky first showed the ballerina role cast to type, with Ulyana Lopatkina, the company’s undisputed queen of adagio. Her interpretation was eerily unearthly, her face tilted slightly toward the heavens, her piercing gaze fixed on a faraway point visible only to such a being as she. I assumed this was an interpretation rather than a rigidly set personal style, since she smiled engagingly once she was participating in the work’s grand finale. Her performance in the duet had the rarefied beauty and the exaggerated, compelling refinement that make many fans love ballet and naysayers loathe it.

A second rendering of the piece was far more musical and relaxed than the first, the company having already proved that it could successfully bring a crucial Balanchine work to the town in which the choreographer’s career matured. It was Yekaterina Kondaurova’s dancing in the second movement that made me decide she’s my favorite in the company’s flock of ballerinas. The others I saw are unquestionably amazing, each in her own way, but often so intent on a high degree of artifice that they seem estranged from humanity. Kondaurova is the only one who makes substance equal to style.

A small but splendid treat of the Mariinsky’s visit was the chance to watch the company’s senior mime, Vladimir Ponomarev, work his subtle Stanislavsky-esque magic. In Anna Karenina he played the elderly servant of uncertain gait and trembling hands who doted, almost pathetically, on Anna. Ponomarev is the sort of artist whose work beguiles you into inventing a character’s past because he makes the figure’s present so believable. I gave the nameless, faithful old man he created a back story of having been with Anna’s family even before she was born and having begged to join her new household when she married. No wonder he’s now reduced to tears by her plight.

In Horse, Ponomarev played the aged, work-ridden farmer, who was father to the three disappointing sons, but I believe he deliberately played the role at one remove, imagining himself to be an over-enthusiastic actor who was part of the multi-referenced fantasy Ratmansky had concocted. When we saw this rural paterfamilias with his boys–two lazy and dishonest, one presumably a fool–he made his gestures rough and exaggerated, the way an itinerant trouper might execute them, feeling all the while very proud of his skills. Simultaneously, he showed another quality, a positively Biblical one, bending his offspring to his will with utmost gravity, like the father in Balanchine’s Prodigal Son. Ponomarev seems to agree with Ratmansky’s idea that people’s personalities and actions can indicate one thing and yet another, even a third, and that this infinite richness is one of life’s gifts.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Deborah Jowitt

I’m delighted to welcome Deborah Jowitt and her blog, DanceBeat, to the small but ardent cluster of dance writers at ArtsJournal. As many readers who have followed Deborah’s writing–some of us for decades–know, her love for our subject is warm, her knowledge deep, her penetration keen, and her writing style distinctive. From my own earliest days at our trade, I learned from her. From our proximity on AJ, I expect I will learn still more.

Alina Cojocaru at ABT

American Ballet Theatre: Alina Cojocaru / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / MAY 16 – July 9, 2011

She’s a darling, Alina Cojocaru–petite, pretty (without being pert or saccharine), fragile-looking as a waif. Her secret, which, of course, she reveals almost immediately after her entrance on stage, is a technical proficiency that would impress you even if her appealing personality–that joy that’s always slightly tinged with sorrow–hadn’t already captivated you.

Cojocaru, who has just completed a third guest stint with American Ballet Theatre in its May 16 – July 9 season at the Metropolitan Opera House, was born in Bucharest, Romania, and trained in Kiev for seven years, eventually joining Britain’s Royal Ballet, where she became a principal dancer in 2001. Today, the lyricism, the exactitude in small things, and the graceful manners of the English style predominate in Cojocaru’s dancing. Still, if you watch closely, you can also see the virtues–such as the projection of both movement and feeling on a large scale–that she acquired from the Russian style of dancing she absorbed in Ukraine.

Split-second Timing: Alina Cojocaru

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Her technique is formidable. Although she’s small, she makes a terrific impact on space, floating or slicing through it, as the occasion demands, churning the air in turns. Her petit allegro, precise and delicate, makes you think of a hummingbird.Ours is an age of superlative technicians. Among the ABT women, triple fouettés are a current fixation and, as inevitably happens, once a single ballerina masters a new feat, a flurry of her sisters will be seen following in her footsteps. ABT’s men have been enjoying a friendly competition as they invent wicked (and sometimes witty) variations on the multiple pirouette. Some–certainly not all, but some–of these marvels make both dancer and audience forget about artistry.

Cojocaru is not likely to forget what she’s about. For one thing, she can act. The commitment to make wordless motion expressive naturally puts an artist on the side of subtlety. What’s more, Cojocaru’s acting isn’t limited to creating a persona and then just hitting the high spots–love, trouble, joyous or tragic outcome–of that persona’s story. No, Cojocaru acts in phrases, each one displaying her character’s response to the situation of that particular moment. And she invariably fuses the series into a whole. The effect makes me think of Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness tactics.

Soul Mate: Cojocaru and David Hallberg in Giselle, Act II

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

New Yorkers got to see Cojocaru in three ballets this season. She offered indelible effects in each. Take Giselle, where she was paired with David Hallberg: Once Albrecht’s perfidy is revealed, Cojocaru begins the Mad Scene as a trusting, now betrayed child, miming “He promised to marry me” and then, for a moment, becoming radiance itself as she recalls their love in broken, feeble mime gestures. The whole stage is hers in this scene–Albrecht, mother, Hilarion, villagers, aristocrats seem to grow dim. She lives entirely in her own world of memory and imagination while, before our own shocked eyes, she slowly self-destructs into madness and dies, in both senses, of a broken heart.

Look, No Hands! Cojocaru and Jose Manuel Carreño in Don Quixote

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Dancing Don Quixote with Jose Manuel Carreño, whose Basilio is one for the history books, Cojocaru gave no hint that she was cast against type. She shot onto the stage in a burst of energy and played a saucy little spitfire–all verve and sparkling footwork. Only once she had laid claim to that type did she begin to show off her exquisite fluidity. Did she manage the Plisetskaya trick, on an exuberant grand jeté, of arching her torso and kicking the back of her head with the trailing foot? Of course she did.

Cojocaru’s balances are famous for the length of time in which she can sustain them without either wobbling or, even more disquieting, visibly worrying about wobbling. In Act III of Don Q, Carreño, obviously acquainted with her mettle, positioned her into a balance on one foot–on pointe, of course–one arm flung up triumphantly, the hand like a tiny waving flag. He then unobtrusively stepped backward and left her there, connected to the earth only by the toes of one foot. They did this twice.

The crowning glory of Cojocaru’s work with ABT this season was her Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty, a portrayal of such beauty, finesse, and dramatic depth, it almost made the awfulness of the production disappear.

Wonderfully musical, she used her keen sense of timing to create a dialogue between the choreography and Tchaikovsky’s score.

As is her wont, she kept the small things small (and as precise as the work of a jeweler), letting the large things flare out so that their images seem to fill the whole stage space and beam out through the house.

She gave a fully nuanced interpretation of Aurora’s experiences at her Sweet Sixteen party–where we first meet her. The princess’s introduction to her quartet of suitors via the Rose Adagio had the look of a real human event with a wide spectrum of believable emotions. Even the (in)famous balances appeared to be a dimension of dancing.

When Aurora pricked her finger on the near-fatal spindle, Cojocaru showed her ricocheting between the fear and confusion she felt as Carabosse’s curse enfeebled her body and attempting to retain her familiar carefree gaiety. She was like a cosseted teenager into whose life nothing bad had fallen until this terrible moment.

In the Vision Scene, looking impalpable was the least of Cojocaru’s achievements. More riveting was her expression of the sorrow and mystery of sleeping (and no doubt dreaming) for seemingly endless hours, days, and years.

The Wedding Scene in this production is such a disaster (blame Kevin McKenzie, Gelsey Kirkland, and Michael Chernov) that not even Cojocaru’s tenderness and incandescence could save it. The grand pas de deux was admirably executed but the surrounding event was so devoid of logic and taste that I began to wish the lovers had simply eloped.

Wedding Belle: Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg in The Sleeping Beauty

Photo: MIRA

Cojocaru’s Prince Désiré was Johan Kobborg, a fellow principal with the Royal Ballet and her real-life partner. Kobborg was born and trained in Denmark, where classical dancing has traditionally been understood to encompass acting. He may not be quite a world-class dancer, but his dramatic skills are superb. When he and Cojocaru dance together you see a dual example of fluctuating mood brought to life, each moment hinting at an emotion that arouses the imagination of the spectator.

Cojocaru is well mated with Kobborg, actually enlarged by him, but he’s compelling on his own, too. He introduces suggestions that may well be his alone (not his coach’s, not memories or videos or photographs of his predecessors). These are not egoistic intrusions; they make you understand the character he’s playing–even the whole ballet–more deeply. For instance, Désiré has his eyes covered by a length of black cloth in a game of Blind Man’s Buff with the frivolous society of his milieu. The moment the blindfold is removed, he sees everything anew–his companions, their trivial world, and himself as an odd man out, a dreamer not yet certain of his dream.

Kobborg doesn’t equal Cojocaru’s stardom but together they make a marvelous theatrical team. Since the newspaper of record has already announced their plans to marry, I’ll take the liberty of wishing them godspeed.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Milestone

American Ballet Theatre: Jose Manuel Carreño’s farewell performance / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 30, 2011

Jose Manuel Carreño bowing to the audience at the close of his farewell performance with American Ballet Theatre

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Is any dancer among us today as much loved as Jose Manuel Carreño? The ardor was apparent at American Ballet Theatre’s June 30th performance of Swan Lake at the Metropolitan Opera House. The occasion was the company’s official farewell to the 38-year-old star playing Prince Siegfried who has been one the pillars of its fame. Yet the evening seemed not so much a regretful goodbye on the part of the dancer and his audience as a celebration of Carreño’s artistry and the personality that informs it.

A brief bio is in order. Born and trained in Cuba, Carreño joined the National Ballet of Cuba headed by the legendary taskmistress Alicia Alonso. After winning a couple of major international competitions, he moved on–to the English National Ballet in 1990, then to the Royal Ballet in 1993. Gradually he realized that, despite all he learned from these opportunities, he and England were ill-matched–the people too buttoned up, the weather too gray–and joined ABT, where he has danced to continuous acclaim since 1995.

Since then, I’ve seen dozens of his performances and can report this about them: The moment Carreño appeared onstage, you sensed his warmth, his erotic appeal, his unquenchable joy in dancing, his generosity, and his impeccable manners. Just a few minutes into the proceedings, his remarkable physical prowess had you gasping. The showiest aspect of it comprised astonishing feats made to look like a form of exuberant self-expression, not, as occurs too often, the material of a second-rate circus. Carreño’s technique was clear and correct yet still sensuous, innately musical (rhythm ran through him), and wedded to harmony of line. Longtime fans have been talking, too, about how, even as the bravura capability that first got him noticed inevitably began to fade, it didn’t matter much for a while, and, when it did, he decided to take leave of the company that had been his home in his physical heyday.

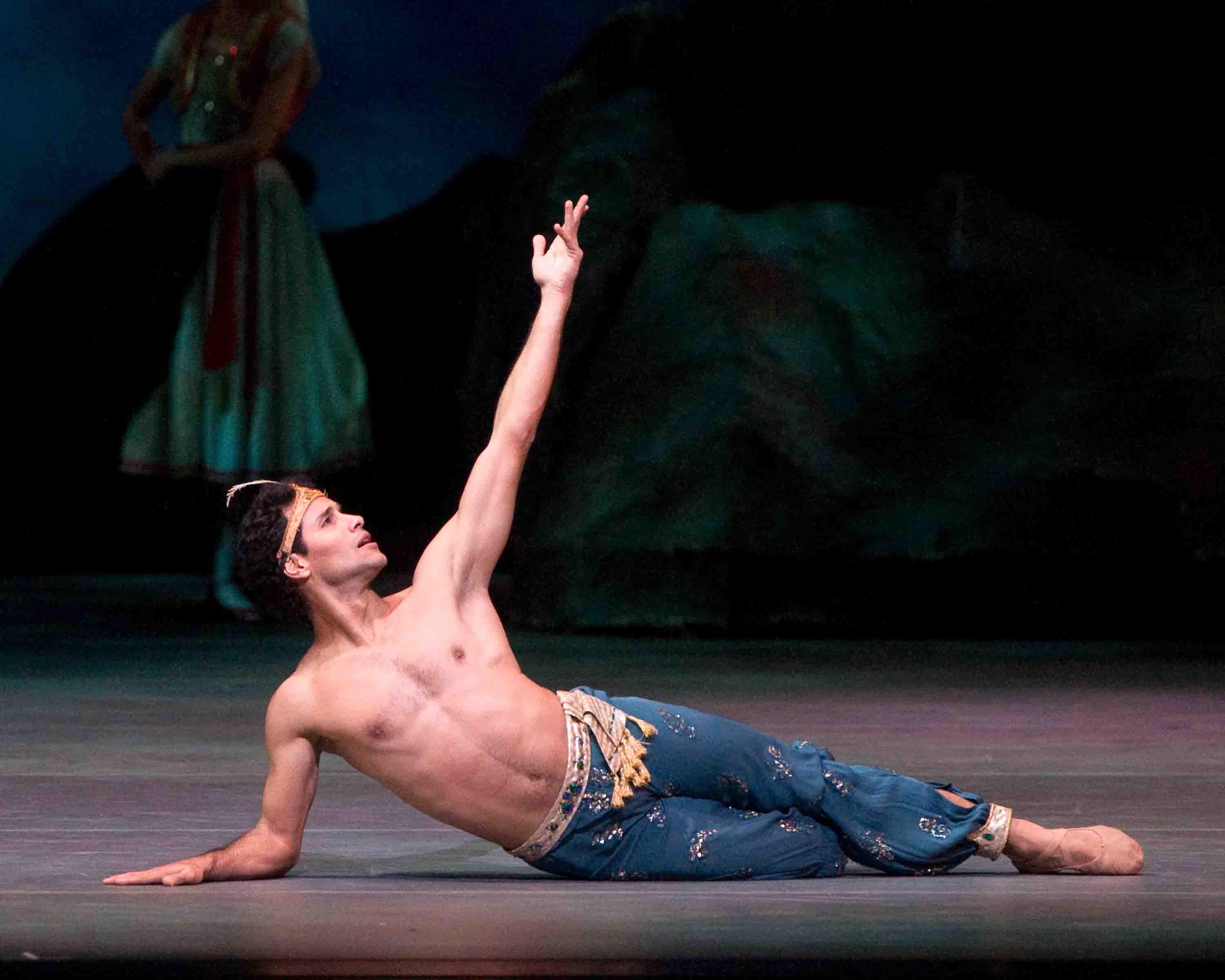

Carreño in the role his fans most identified with him: Basilio in Don Quixote

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

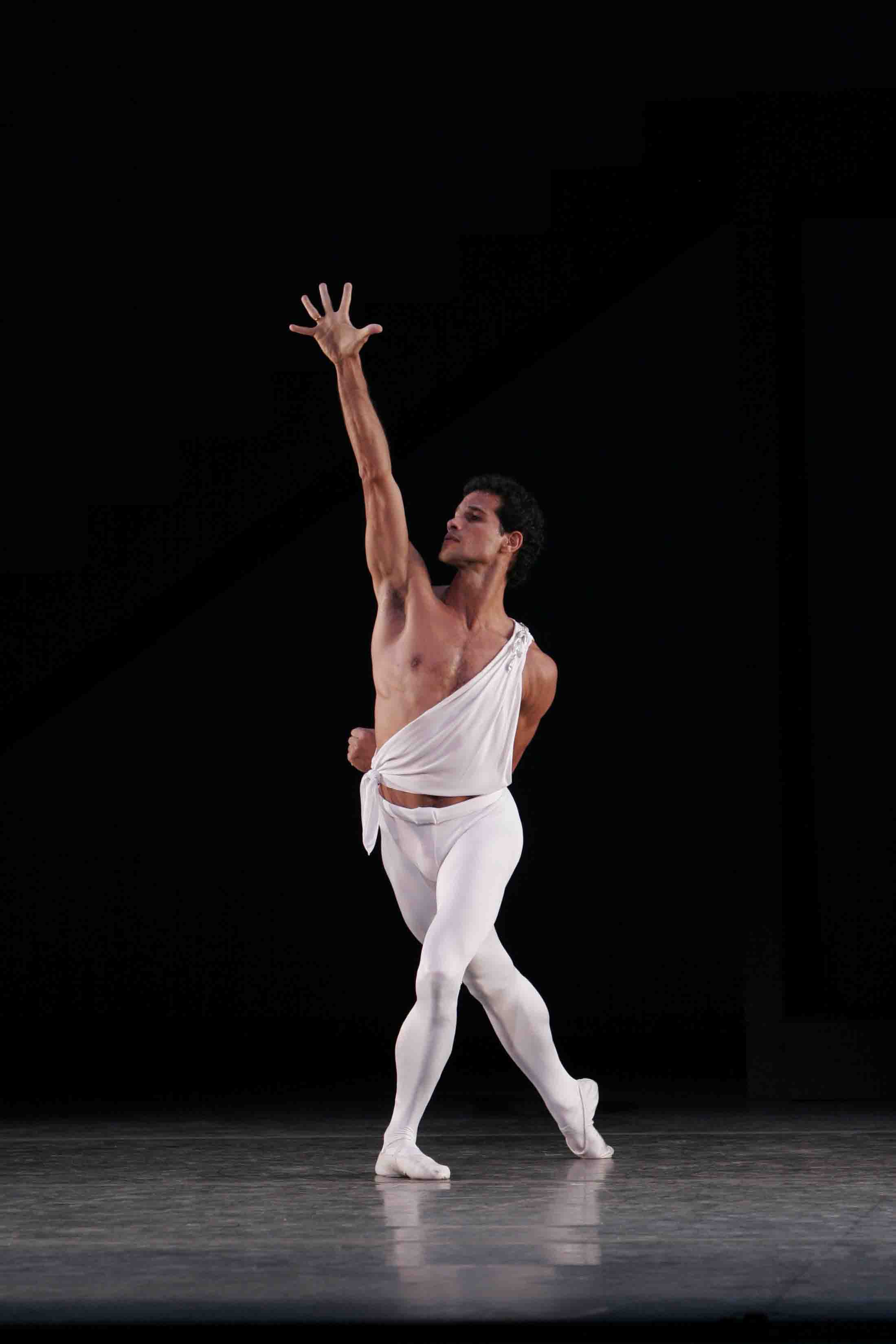

Carreño performing the title role in George Balanchine’s Apollo for ABT

Photo: Marty Sohl

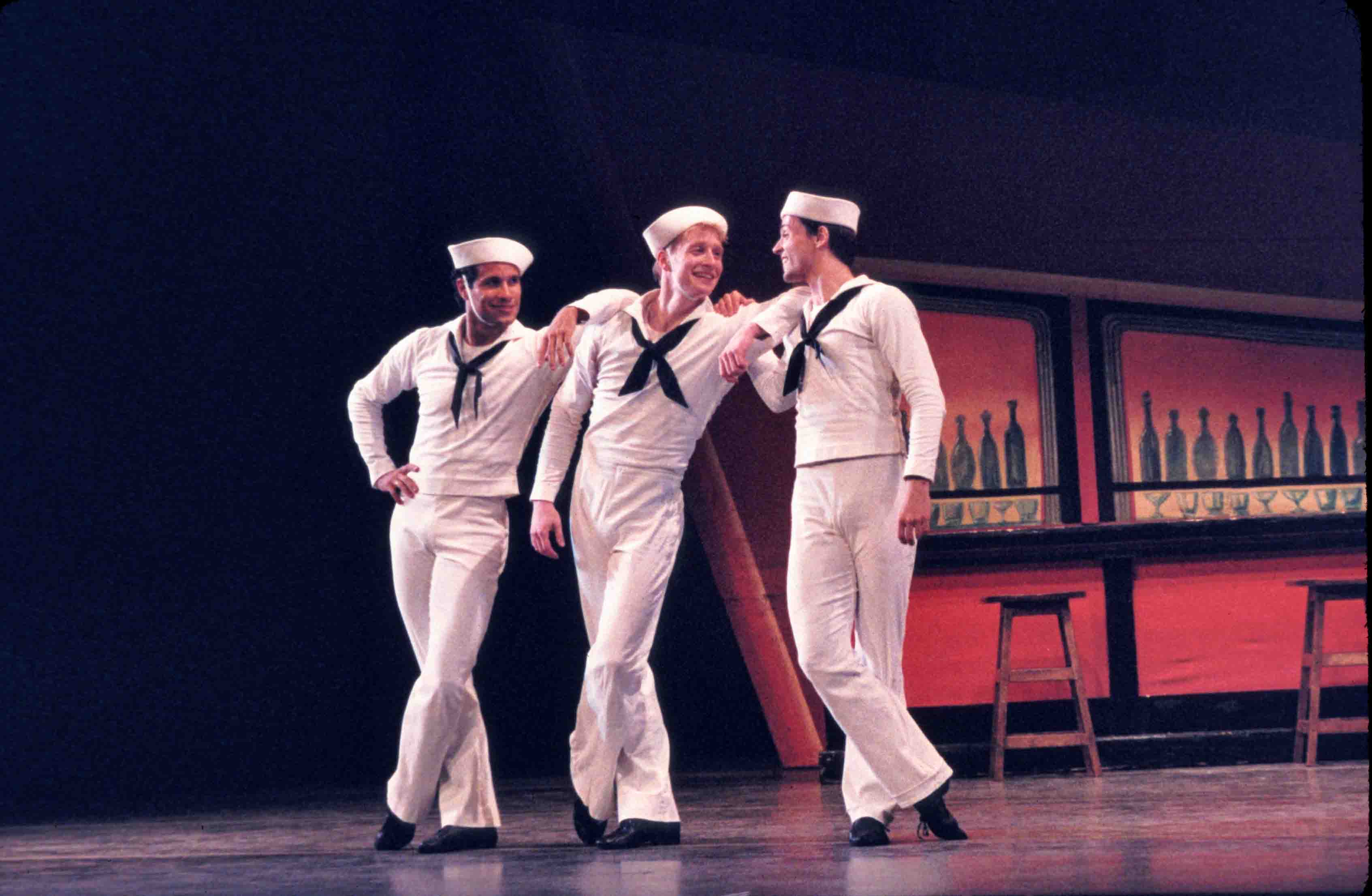

From left: Carreño, Ethan Stiefel, and Angel Corella in Jerome Robbins’s Fancy Free

Photo: MIRA

Carreño has been wonderful in both classical and contemporary roles. He’s played just about all the danseur noble roles in the international repertory, from Albrecht to Apollo, and was equally comfortable in the more slangy styles of Jerome Robbins and Twyla Tharp. If classical ballet, 19th-century style, didn’t convince a viewer that Carreño was terrific–and a heartthrob, to boot–this resistance would likely be overcome by his performance in Robbins’s 1944 Fancy Free, which charts the adventures of three sailors on leave in New York. He played the part Robbins created for himself, the guy who does the sexy rhumba with the chair.

As many a grateful ballerina has attested, Carreño has also been the ultimate cavalier, infallibly gracious to his partner, whoever she might be. It’s as if “Woman” were a generic character in his stage life, eliciting from him an instinctive response of deference and devotion, to say nothing of astute partnering.

Despite the fact that farewell performances often require the audience to take on faith the best achievements of the honoree, Carreño’s was thrilling in and of itself.

He was surrounded by friends. Two of his most frequent partners split the leading female role between them, as has occasionally been done in the past, to tailor the technical challenges to each ballerina’s specific gifts. Julie Kent was the epitome of poignant regret and fragility as Odette (the white swan); Gillian Murphy, a voluptuous, witchy daredevil as Odile (black). Susan Jaffe, a third ballerina with a long history as Carreño’s partner, came out of retirement to play the Queen Mother. Cast as Benno, Joachim de Luz–a close pal from earlier ABT days, who’s now with City Ballet–added sparkle to the Act I pas de trois. Melanie Hamrick, Carreño’s fiancée (as was recently announced in the New York Times) was featured in the Spanish Dance and as one of the two swans who do the weighty mirror-image adagio passage that underlines the swans’ communal sorrow. In truth, though, it seemed that the entire company was working as a united force to make the performance as splendid as Carreño deserved.

Carreño himself danced the way, perhaps, he dreams of dancing; everything worked, his gifts and his current abilities coalescing. He nailed each of his solos. The virtuosic demands were well considered, ably met, and finished with neat, cushioned landings, while Siegfried’s melancholy solo when he feels alone and loveless in a crowd of his paired-off friends, was handsomely sculpted and beautifully acted. Performances like this come only rarely in a dancer’s life, and usually at a poorly-attended matinee on a rainy Sunday. Here, with some 4,000 pairs of eyes fixed on him alone, there were many passages that must have made the spectators wonder why the guy was retiring at all.

Carreño and dancers of ABT in Le Corsaire

Photo: Gene Schiavone

True, his leaps these days are not what they once were. They’re softer in attack and lower at their peak. Still, now as well as back then, for a dancer who always seemed so much more of-the-earth than most danseurs nobles, he appears very light in the air–not ethereal, but simple very light, as if gravity had reduced its claim and the air itself made him buoyant.

Turns are Carreño’s specialty and his continue to be unsurpassed in their finesse. Throughout his ABT career, as I recall, he was in the forefront of inventing variations on multiple pirouettes–as with the working foot poised at the knee of the standing leg and then, with a barber-pole effect, stealing down the standing leg to hug the ankle. Lately, while still swiveling smoothly, he can make the working foot sneak upward again. He can also diminish the speed of a multiple pirouette so that it starts out ferociously energetic and finishes in a contemplative calm. Such inventions, adopted by his peers and the rising generation of standout men, enliven and enrich the ballet vocabulary though they occur so naturally, we hardly notice them.

Time has only enlarged Carreño’s adroit partnering skills. In terms of physical support, he’s keenly sensitive to what his ballerina needs, how much, and when. At the same time he builds an emotional rapport between her character and the way she’s playing it and his. Everything he does is governed by a self-effacement that seems to be central to his temperament. Though his stardom is indisputable, he tempers it with humility.

Carreño in his farewell performance with ABT, dancing Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake with Julie Kent as Odette

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

In his response to Kent’s Odette, he gauged his presence and held back in intensity. He was never not there, but he never overwhelmed her. The music for their lakeside pas de deux was taken at so slow a pace–presumably requested–that it provided a gossamer surround for the ballerina’s fragility. Carreño performed as if the character Kent had devised for herself were the most important element in the ballet–as if, indeed, he’d forgotten to whom the evening was dedicated.

Carreño in his farewell performance with ABT, dancing Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake with Gillian Murphy as Odile

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

With Murphy, he matched both her physical challenges (which were spectacular, such as triple fouettés enlivening the obligatory 32 singles) and the nearly excessive excitement with which she played the temptress. In their pas de deux he even smiled for a few seconds like someone having an indecently good time; then let some doubt that Odile was his beloved Odette shade his face; next quietly and sweetly surrendered himself to Odile as her prey. Given the mounting incendiary quality of their match, the firebomb explosion when the villains’ duplicity was revealed seemed a crude afterthought.

Some of the wonders Carreño worked were very small and subtle, yet they registered large as moments charged with meaning–and magic. An example: At one point Siegfried is searching, futilely, for Odette among the lamentation of swans; then she enters the stage from behind him and he seems to feel her presence at the nape of his neck. Carreño’s expression of Odette’s effect on him–simply through her being near him, before he turns his head to see her–is an effect I’ve witnessed only in classical Japanese theater. I’ve seen it attempted in Giselle of course, but never convincingly.

From Carreño’s farewell performance with ABT: Carreño (center, with bouquet); to his left, David Hallberg; to his right, Kevin McKenzie, ABT’s artistic director

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Then, the bows, always the final act of such an occasion. As the curtain fell on Swan Lake the spectators in the packed theater rose as one, applauding and shouting their acclaim. First the full cast, much of it in white feathers, bowed. Then the dancers of the solo parts, and then the principals: David Hallberg who’d been spectacular as the licentious von Rothbart (a dancing role in the current ABT production), then Carreño and his two ballerinas.

As the sequence was repeated, Carreño kept the pair of ballerinas by his side as long as he could before he allowed himself to take a solo bow. Needless to say, it elicited roars from the house. Murphy and Kent had retreated to the sides of the stage and, with the rest of the cast, were applauding Carreño who, turning his back toward the audience, knelt and bowed his head in homage to the company.

While all this was going on, red and white flowers were hurled from the heights of the auditorium and flung over the orchestra pit. No sooner had a more formal presentation of tributes concluded than a parade of Carreño’s colleagues marched onstage from the wings, one by one, to deliver embraces along with their own floral offerings–so many that the bouquets and laurel wreaths had to be laid to rest on the floor, where the petals and leaves, gently crushed, formed a mound of tribute.

After another round of bows for the principals in front of the Met’s iconic golden curtain–mind you, the applause went on steadily for some 15 minutes–Carreño, by now weeping between smiles, took his last bow, one arm around each of his lovely, raven-haired teenaged daughters. No confetti. No helium balloons. They’d have been a frivolous distraction at an event that anatomized devotion.

ABT’s Jose Manuel Carreño in the company’s production of Le Corsaire

Photo: MIRA

Carreño’s future in dance is assured. He talks about the possibility of guest appearances with ABT and beyond. He’d love to perform on Broadway or in film. He is also already celebrated as a teacher, working with the boys at the School of American Ballet (New York City Ballet’s academy) and giving company class at ABT. This summer he’ll offer a comprehensive summer program for the young, the Carreño Dance Festival, in Sarasota, Florida. Perhaps he’ll have more time for some favorite diversions: playing tennis, exercising his salsa chops in the clubs. We won’t see as much of him, but we’ll never forget him.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias