The second company of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, may be chamber-size, but its young dancers possess enough exuberance to fill a stadium. (Hubbard Street 2); No reference here to the legendary Elssler’s sensuous allure. No nod even to the lush waltzing that’s the national dance of Straussville. (The Ballerina Fanny Elssler) Village Voice 11/19/03

POST-MOD WEATHER REPORT

Rosas (Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker) / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / November 12-17, 2003

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rain, performed by her Belgium-based company, Rosas, draws upon defining devices of early postmodern dance—the inventions and innovations of the late 1960s and the 1970s—and gives them a sleek, forceful theatricality. Indeed, it makes them fit for an opera house—the venue, laden with tradition, on which postmodernism originally turned its back in contempt. Such a development is both ironic and inevitable—the mainstream is a magnet for the work of its rudest antagonists—and De Keersmaeker’s piece is very handsome indeed.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rain, performed by her Belgium-based company, Rosas, draws upon defining devices of early postmodern dance—the inventions and innovations of the late 1960s and the 1970s—and gives them a sleek, forceful theatricality. Indeed, it makes them fit for an opera house—the venue, laden with tradition, on which postmodernism originally turned its back in contempt. Such a development is both ironic and inevitable—the mainstream is a magnet for the work of its rudest antagonists—and De Keersmaeker’s piece is very handsome indeed.

The pictorial aspect alone is stunning. The setting, designed and lighted by Jan Versweyveld, is a circular amphitheater demarcated by a curtain of hanging cords. It might be a field of prowess or combat; a stage, like the Greeks’, for theatrical endeavor; or perhaps the planet Earth, surrounded by a nebulous cosmos. The lighting bathes the structure in a pale golden glow, a cross between the qualities of sun and moon. The scene darkens several times, in response to the course of events, but never looses its immanence.

The dancers’ simple, casual costumes—by the Belgian couturier Dries Van Noten—echo the neutral pallor at first. Unobtrusively, as the piece progresses and the energy of the dancing intensifies, their palette shifts to include livelier colors: bright raspberry, flame, and damped-down tangerine. It shifts again as the dance winds down, subtracting the brighter hues and substituting the sheen of ivory satin, the glitter of metallic thread, as if to indicate that the wearers have earned celestial status.

Seated in a ring behind the cord curtain, visible as through thin-bladed half-open window blinds, black-clad members of Ictus and Synergy Vocals perform Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians, a hypnotic score typical of those used by pioneer postmodern choreographers, once they capitulated to using music at all.

Rain opens with movement that looks very natural—well, choreography-style natural—emphasizing running and loosely flung limbs. It builds gradually but inexorably, adding to its modern-ballet base gymnastic feats and inflections from foreign climes—capoeira and the like—all relying on elastic joints and quick reflexes. Buoyed by the mesmerizing music, the action goes on for seventy minutes without a break, accreting into one of those feats of sheer endurance that audiences love to greet (and did on opening night at BAM) with standing ovations.

The piece begins with a longish stretch of ensemble work in which all of the figures have equal importance. Eventually the group of ten dancers (three men, seven women) breaks down into smaller units—septets, trios, duets, even brief solo turns—woven with masterly skill into the picture of the whole population. Midway, a long passage suggests the community’s selecting one of its young women for a rite-of-spring-style sacrifice. Instead of building to fever pitch, though, the idea is deliberately allowed to blur. The victim is excused and allowed rejoin the clan, another is chosen, and then the whole matter is dropped, almost absent-mindedly, the myth seemingly depleted of its significance, given the current climate of the imagination.

Another, more specifically erotic motif succeeds the sacrificial-virgin idea. Men carry off women in Rape of the Sabines style, and images of intercourse–earlier brief, casual, and affectionate—mount to an extended explicit coupling of some violence that both participants appear to relish. (Is there a pc agenda at work here?) Still, the motif of the anonymous ensemble, activated but essentially purposeless, recurs frequently, often as a lineup of the full cast moving across the stage like a windshield wiper, clearing it of specific events and feelings. And yet, and yet . . . even in these essentially uninflected lines, you spy a couple arm in arm, because humanity can’t do without one-on-one bonding and can’t help telling stories (or at least, to the watcher, appearing to do so).

Watching is RAIN’s watchword. At intervals the dancers arrange themselves in a flat frieze and gaze directly at the audience. There’s nothing confrontational in this; it’s just an acknowledgement that they know you’re there—freighted, however, with the implication that, if you weren’t there watching, they and their doings wouldn’t exist. The audience might be God; the dancers, the world s/he created. The performers keep stopping for a nanosecond to look frankly and pointedly at one another, too, and seem pleased by what they see. Adam and Eve? Whenever the choreography focuses on the doings of just a few of the group, other members of the little tight-knit tribe gather on the sidelines to observe. The lookers-on are neither sympathetic nor cruelly impassive; they are simply there, bearing witness with enigmatic calm. (Oddly enough, there are similar happenings in Balanchine’s Serenade, but that is another story.)

About three-quarters of the way through De Keersmaeker’s venture, the dancers begin to emit wordless cries of exertion and excitement. These raw, guttural vocals lead to their escaping from their cage. They plunge recklessly through the cord curtain that contained them to invade the musicians’ space, then surge back into their own, as if the original boundaries agreed upon for performance had proved inadequate or artificial, limits crying out to be destroyed. As the dancers’ behavior grows more and more transgressive spatially, their dancing aspires increasingly to Dionysian intensity, until the music climaxes and halts. Stilled by silence, they animate the curtain that enclosed them with one final wave-like slash and vanish, perhaps en route to an alternative universe.

The message here would seem to be that, ultimately, the life force can’t be controlled, not even by whatever gods may be. De Keersmaeker, though, is clearly in control—she’s a deft calibrator—and it’s this evident calculation in the staging, this canny use of both traditional and postmodern theatrical devices, that makes Rain more a clever synthesis of latter-day dance theater explorations—a summary of and perhaps even a conclusion to them—than a blazing, gratifyingly discomfiting breakthrough.

Photo credit: Stephanie Berger: Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rain

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Noche Flamenca; “Black Burlesque (Revisited)”

[Soledad Barrio] can access the deepest, most primal feelings and project them directly to her audience. Impelled by will and imagination, she turns herself into an engine of arousal and destruction. (Noche Flamenca) [An] infectiously joyous show, which proves that distinctive ingredients need not be diminished or obscured when they meet and mix. (Black Burlesque [Revisited]) Village Voice 11/12/03

DANCE TO THE PIPER

George Piper Dances / Joyce Theater, NYC / November 4-9, 2003

George Piper Dances, at the Joyce through November 9, is named for the conjoined moniker-in-art of Michael (middle name: George) Nunn and William (Piper) Trevitt. The pair of Brits with charm to spare and an unexpected taste for austere, ostensibly cerebral choreography are also known as the Ballet Boyz, after the title of a popular T.V. series they did on dancers’ backstage and offstage lives (a subject of enduring public curiosity).

Brief chronology: Pals at the Royal Ballet’s august academy, Michael and Billy (as he prefers to be called) went on together to put in a dozen years with the parent company, rising out of the corps to the rank of First Soloist and Principal respectively. Gradually they found their jobs to be same old same old, and their discontent was exacerbated by internal roiling in the grand old institution. So off they went to do their own thing, to “make it new,” as feisty artists have longed to do since modern times began. A venture called K Ballet in Japan turned out to be insufficiently high art for them, hence George Piper, founded in 2001.

Brief chronology: Pals at the Royal Ballet’s august academy, Michael and Billy (as he prefers to be called) went on together to put in a dozen years with the parent company, rising out of the corps to the rank of First Soloist and Principal respectively. Gradually they found their jobs to be same old same old, and their discontent was exacerbated by internal roiling in the grand old institution. So off they went to do their own thing, to “make it new,” as feisty artists have longed to do since modern times began. A venture called K Ballet in Japan turned out to be insufficiently high art for them, hence George Piper, founded in 2001.

Last spring, Nunn and Trevitt worked up Critics’ Choice *****, a program of short pieces by five contemporary choreographers they admired intercut with videotaped documentation of the works’ creation—the idea being to show how each choreographer operates. The Joyce program continued the policy of offsetting the live dance numbers with hyperactive video footage that may not reveal all that much about the creative process but vividly presents the Ballet Boyz as regular guys, modest and dedicated to their work, at the same time wry and irreverent—in other words, apt candidates for popularity.

Five dancers performed the Joyce bill of three strenuous works: Trevitt and Nunn, along with Hubert Essakow (another ex-Royal) and a pair of killer-chic women from elsewhere, Oxana Panchenko and Monica Zamora. The dances were uniformly abstract, with long monotonal stretches and minimal affect—a programming flaw guaranteed to make the most resolute modernist sensibility succumb to a momentary longing for a story, a recognizable character with a self-evident problem, even a swan.

William Forsythe’s 1984 Steptext, which opened the show, stated the adamantly non-objective aesthetic that was to prevail. Set to shards of a Bach chaconne, it glamorizes ferocious mean-mindedness. The dancers labor arduously in isolation, handsome and fraught, or in couple work that masks deft physical cooperation with a confrontational attitude. A repeated motif consists of raising the arms, right-angled at the elbow, and beating the fists together. Someone—the other guy, the whole goddamn world—is angling for a fight. Much of the action suggests the disjunctive dancing that takes place in rehearsal—isolated bits and pieces that cut off abruptly, impatient waits for musical cues, frustrating passages of partnering that don’t cohere. Of course, if you’ve a mind to, you can take this stuff as a metaphor for life itself. Or, if you prefer, you can fret over the way Forsythe’s women get manhandled, despite their own tough hostility. At one point, the growing menace of silence is broken by the music, whereupon the stage lights are extinguished, and the audience sits watching a dance it can’t see.

Christopher Wheeldon, Resident Choreographer at the New York City Ballet and the rising youngish hope of the ballet community, provided the show’s most attractive piece, Mesmerics, expanded to quintet status from its earlier trio form. Set to a kaleidoscope of Philip Glass music, the dance centers on an elaborate, languorous twining of long, svelte limbs, often with the dancers splayed out on the floor. They might be underwater swimmers, even dream figures enacting a wordless romance, except for the fact that brute strength clearly underlies their grace. Erect, the dancers travel on lateral paths, arms wheeling occasionally, as if as if tracing brief moments of turbulence on an infinite timeline.

As always with Wheeldon, everything that happens is beautifully contrived, carefully placed in a scrupulous architectural structure. The piece maintains its look with a consistency you’ve got to admire, yet this thoroughgoing adherence to pattern suggests an unfortunate cousinship with sleek interior decoration. Although the piece eventually achieves some mounting intensity, little happens that’s unexpected, nothing occurs to disturb the universe as the choreographer first proposed it. I admire Wheeldon’s skill, but I distrust his impulse. To me, all his exquisitely crafted dances seem to be fashioned from the outside in. They may look terrific, but they fail to accomplish one of art’s first duties—shaking up the mind or the heart.

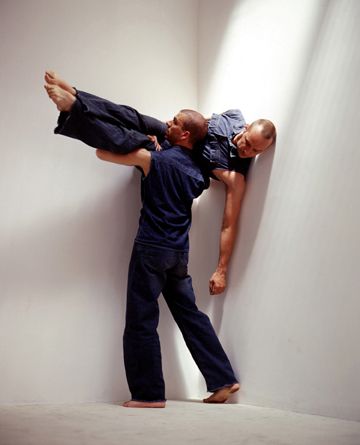

A duet for Nunn and Trevitt, seemingly based on the dancers’ close friendship, Russell Maliphant’s Torsion relies on that oh-so-yesteryear tactic of combining movement genres that (1) have little in common and (2) are absent from the curriculum of traditional dance academies. Contact improvisation dominates here, seconded by devices from capoeira, hip-hop, yoga et al. The friendship business goes on forever, oddly blue in tone, as if togetherness were impossible to maintain or reclaim, and dismayingly dependent on the partners’ alternately outstretched and clasped hands. And here we were thinking, from the upbeat sophomoric humor of those videos, that the boyz were going great, their bond so firm and cheerful. If the audience is not to confuse life and art, then George Piper should not employ strategies encouraging it to do so.

Things to know, if you believe the folks who say that GPD represents the future of classical ballet, an art they claim is dying on its feet: (1) Classical ballet is a technique that can serve anywhere. Wheeldon is essentially operating in it, using newfangled stuff largely as ornament. Forsythe seizes parts of it as his heritage then proceeds to conduct an ongoing argument with it, sometimes with inventive results. Even Maliphant, with his polyglot, anti-Establishment movement vocabulary, falls back on it when he thinks you’re not looking. (2) Classical ballet is also an art form that, like opera, is most itself when it can operate with a goodly number of performers in a sizeable house. The court ballets of Louis XIV’s era, the ballets of Petipa, and most of Balanchine’s and Ashton’s memorable works depend on generous dimension and on a hierarchy that distinguishes among principal, soloist, and ensemble ranks for choreographic purposes. Corps de ballet, remember, may be translated as “body of the ballet” and the power of a group moving in unison is not to be underestimated (as military parades prove). To be sure, there are unforgettable chamber-scale ballets (think of Ashton’s Monotones), but a repertory consisting solely of small numbers, even if they’re gems, offers its audience a very limited experience.

Another thing to know: Even with the purest of intentions—for the sake of argument, let’s credit the Boyz with these—it may be impossible to engage a broad audience with highbrow “advanced” choreography. Mikhail Baryshnikov had a splendid go at it for some years with his White Oak Dance Project on the strength of his name and his gifts as a dancer even after age and injury eroded the virtuoso aspect of his powers. But, to paraphrase Lincoln Kirstein—who masterminded Balanchine’s career, to say nothing of the development of the New York City Ballet as an institution—ballet is simply not destined to interest as many people as football does. There are indeed ballet moms as well as soccer moms, but a huge difference remains in their numbers. While George Piper Dances is fine and dandy, Nunn and Trevitt might do well to concentrate their considerable talents and energies on expanding the scope of their repertoire instead of trying to make themselves household words.

Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning: Michael Nunn and William Trevitt in Russell Maliphant’s Torsion

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

PATCH WORK

American Ballet Theatre / City Center, NYC / October 22 – November 9, 2003

American Ballet Theatre’s annual fall season at City Center, now expanded from two weeks to three, looked foolish even before the curtain went up.

A new marketing ploy organized the repertory being offered into four set programs. The most misguided of them, “Innovative Works,” served up Nacho Duato’s Without Words, William Forsythe’s workwithinwork, and Within You Without You: A Tribute to George Harrison, choreographed by various hands, including David Parsons, who has a deft finger on the pulse of popular taste. “The W Show,” as I came to think of it, restricted itself to presenting dancers clad for today–in unitards, low-slung jeans, and gloom. I assume it was designed for folks who feel threatened by tutus. Only the Forsythe piece, a strong, concise example of his post-Balanchine style, was worth a moment of one’s time.

This inflexible system all but guaranteed the annoyance of potential ticket buyers with some knowledge of the art. For instance, Balanchine’s diamond-brilliant celebration of classical dance Theme and Variations could be seen only at the opening night gala or the “Family Friendly” matinees, occasions that tend to be undermined by restless audiences (the all too rich and the all too young). It created a few delicious absurdities as well. Agnes de Mille’s charming revue-style romp from 1934, Three Virgins and a Devil, also relegated to gala/matinee position, may well have entertained underage spectators, but surely it occasioned a dubious instructive opportunity: “Mommy, what’s a . . . ?”

The issue of virginity also dominates Antony Tudor’s 1942 Pillar of Fire, given the imprimatur of placement on the “Master Works” program, as if its being one of the twentieth century’s most potent dramatic ballets–a searing essay on sexual repression, revolt, and redemption–were an insufficient guarantee of its worth. Donald Mahler, apparently the official purveyor of Tudor to ABT, staged this revival, and I attribute its failings largely to him. His productions of Tudor, attentive to detail, invariably lack a governing theatrical impulse. Watching them is like looking at a picture painted by numbers. The discrete images are there, but they don’t quite cohere, and they don’t seem driven by an intense vision. I wonder if Sallie Wilson, once a notable ABT interpreter of Tudor roles, who now mounts Tudor’s choreography elsewhere, might be more capable of restoring the essential dynamics to this ballet.

Granted, the present time has not cultivated dramatic dancers like Nora Kaye, who originated the role of Pillar‘s tormented heroine, Hagar, and brought to it a turbulent force at once physical and psychological. Gillian Murphy, distinguished by her grandeur of body and technique, is promising in the part, but as yet almost adamant in her refusal to let Hagar’s situation and feelings engulf her. Julie Kent–an ethereal beauty, and thus cast against type–is naturally too fragile in style (Hagar’s plight is not an occasion for delicacy) and, like Murphy, too placid, almost immune to what Tudor tells us is going on. Toward the end of the ballet, though, she offered a glimmer of authentic feeling. (I’m writing this before Amanda McKerrow takes her turn in the role.) In both casts I saw, the character of Hagar’s male foils–the one who offers her sex (Marcelo Gomes; Angel Corella) and the one who offers her sympathy and a future (Carlos Molina; David Hallberg)–hadn’t cohered. Only Xiomara Reyes, as the little minx of a younger sister, is already perfect in her part.

Granted, the present time has not cultivated dramatic dancers like Nora Kaye, who originated the role of Pillar‘s tormented heroine, Hagar, and brought to it a turbulent force at once physical and psychological. Gillian Murphy, distinguished by her grandeur of body and technique, is promising in the part, but as yet almost adamant in her refusal to let Hagar’s situation and feelings engulf her. Julie Kent–an ethereal beauty, and thus cast against type–is naturally too fragile in style (Hagar’s plight is not an occasion for delicacy) and, like Murphy, too placid, almost immune to what Tudor tells us is going on. Toward the end of the ballet, though, she offered a glimmer of authentic feeling. (I’m writing this before Amanda McKerrow takes her turn in the role.) In both casts I saw, the character of Hagar’s male foils–the one who offers her sex (Marcelo Gomes; Angel Corella) and the one who offers her sympathy and a future (Carlos Molina; David Hallberg)–hadn’t cohered. Only Xiomara Reyes, as the little minx of a younger sister, is already perfect in her part.

Another masterwork, a revival staged by Wendy Ellis Somes of Frederick Ashton’s 1946 Symphonic Variations proved to be the chief of the season’s pleasures. This infinitely serene dance for six, set to César Franck’s Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra, is about as abstract as dance can get. Nevertheless, it projects a strong atmosphere of hard-won serenity, of calm after storm, of people resuming their communal lives after devastating disruption. The date of the work–1946–is a clue to the meaning embedded in the choreography. When, as they periodically do, the dancers run in a serpentine pattern across the stage, linking hands as they travel to form an ephemeral human chain, it would be hard not infer a message about life’s fragility and the unquenchable human desire to reclaim territory and connections after even the gravest violence has been done to them.

However one chooses to interpret the dance, its overall effect is one of sublimity. This is odd, considering how much of the movement in Symphonic Variations is most peculiar. Time and again, the use of the arms and hands systematically contradicts balletic convention. The arms frequently extend straight from shoulder to wrist instead of rounding softly. They thrust athwart the torso rather than graciously framing it. They shield the head, masking expression. The hands stray from their prescribed cupped position, fingers arranged like tendrils, to an emphatically closed, flat one, sometimes sharply angled from the wrist. Even odder is the fact that these deviations from the classical norm actually blend in with the lovely acquiescence to its rules that prevails in the ballet, the new and strange being absorbed into the old and, what’s more, enhancing it. Is Ashton giving us an illustration of how the academic dance ballet vocabulary has evolved?

Every member of the first cast (the second hadn’t performed at press time) looked dedicated to getting the dance right, and the purity and steadiness of this aspiration was, in itself, infinitely touching. Thus far, Ashley Tuttle, an exemplar of the classical style in its gentle mode, is the only one in the sextet to achieve the illusion of repose ideal for the choreography. Her accomplishment is evident both in the harmony and composure of her dancing and in the moments–one of the ballet’s most telling motifs–when she’s utterly still, like a breathing statue or a Zen practitioner, just being. Tuttle’s role was originated by Margot Fonteyn, and her rendition of it, though utterly free from the strains of imitation, serves as a homage to her predecessor.

Providing a certain requisite dazzle, the company offered an excerpt from Marius Petipa’s 1898 Raymonda. Staged by Anna-Marie Holmes, who specializes in the nineteenth-century Russian classics, and ABT’s artistic director, Kevin McKenzie, the ballet is slated for performance in its full-length guise during the company’s 2004 spring season at the Met.

Over at the New York City Ballet, George Balanchine, who, at various times, excerpted the segments of Raymonda that remain viable for a contemporary audience, seemed fully aware that, despite its glorious Glazounov score, the whole show, with its murky narrative set in medieval Hungary, will no longer fly. ABT, from earlier attempts of its own to resurrect a surround for the indisputably marvelous passages in the choreography, should know this too. Maybe some audience survey, revealing the general public’s yen to be told a story in a lavish setting, persuaded ABT’s management to try again. (Management has never been known for a firm aesthetic stance.)

This season gave us a preview of the upcoming production, the “Grand Pas Classique,” which provides legitimate occasions for that ABT specialty, male pyrotechnics, along with the show-offy glamour of svelte, smiling beauties arrayed in fur-trimmed tutus. More important, it contains splendid choreographic inventions–a solo for the ballerina that’s inflected with signature moves from the czardas; a male quartet based on the camaraderie and competition at the heart of male bonding; and experiments with the hierarchical distinction between soloist and ensemble that are strikingly forward-looking.

Things weren’t going too well yet at the performances I saw, one led by Paloma Herrera and Jose Manuel Carreño, the other by Michele Wiles and Carlos Acosta. The text for the male lead’s big solo seemed to adhere to the instruction “Don’t worry, it’s not set in stone. Just do your flashiest steps.” The pas de quatre guys, having established a gracious, genial relationship, flubbed the series of double air turns that’s the element everyone remembers from their material. Meanwhile, the ballerina role is crying out for intensive coaching from Martine van Hamel, who, in earlier ABT versions, embodied just the right dual image for Raymonda: tsarina of Imperial Russia and gypsy full of secrets, many of them erotic.

On the “Contemporary Works” program, a matched pair of acquisitions created by the celebrated Jirí Kylián, whose home base is the Nederlands Dans Theater, were juxtaposed with a home-grown novelty, Robert Hill’s Dorian. Hill has taken as his springboard Oscar Wilde’s macabre, titillating tale in which a narcissistic man remains young and beautiful in appearance while his portrait registers the progressive corruption of his soul. The family unfriendly subject matter is undeniably tempting, but Hill simply doesn’t possess sufficient craft to re-animate–in terms of ballet–the narrative, the characters, or the lusciously decadent mood of his literary source. The mime necessary to convey the scenario is not so much acting as “sort of” dancing, which leaves matters vague, while the set pieces of dancing, which should spring from the story line like aria from recitative, are so thin, pallid, and predictable as to seem nonexistent. In the course of the near hour it took for Dorian and his doppelgänger to come to their horrific end, I couldn’t help wondering, What would Antony Tudor have done?

Despite follies of programming, casting, and coaching and the perennial tug between the concerns of commerce and those of art, the ABT season repeatedly delivered little miracles. One instance of utter perfection: the Cornejo siblings, Erica and Herman, as the Couple in Yellow in Martha Graham’s Diversion of Angels. Light, swift, exuding joy–working, rightly, from a gut-sprung base–they equal, perhaps surpass, the finest Graham-bred exponents of the roles that I’ve seen. On them, the choreography that classical dancers struggle with because it is basically alien to their training suddenly, astonishingly, looks spontaneous.

Photo: Marty Sohl: Marcelo Gomes, Gillian Murphy, Erica Fischbach, Xiomara Reyes, and Carlos Molina in Antony Tudor’s Pillar of Fire.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

KISSING COUSINS

Susan Marshall & Company / BAM Harvey Theater, New York City / October 21-25, 2003

In our current climate of branding, dance concerts must have titles.

The choreographer Susan Marshall, already branded as a genius by her copping a MacArthur Fellowship 2000, slyly called her latest program, part of BAM’s Next Wave series, Sleeping Beauty and Other Stories. The words on both sides of the (pointedly unitalicized) “and” are simply the names of her two newest works. The first is one of the finest efforts of her career.

Like the landmark Marshall pieces Interior With Seven Figures (1988) and Arms (1984), Sleeping Beauty, while pretending to be abstract, evokes the poignancy of the human condition. It takes as a given the darkness in which we all operate, acknowledges the basic futility of human relationships, yet charts (and celebrates, I think) the persistence with which we doggedly continue trying to make them work—as if our identity depended upon the hope-fueled effort. All of this is done so unemphatically, with so much sheerly visual gratification along the way, you hardly know what’s happening to you until the piece ends and your emotional experience has been so profound, you can barely move or speak.

For Sleeping Beauty, Douglas Stein has provided a stern beauty of a set. Multi-paned crackle-glass panels partition the space, creating an open field framed by semi-private corridors. Through the panes, tiny windows offering different degrees of translucency, both dancers and viewers can see variously—fully, partly, or not at all. Huge work lights hang high above the dancing ground, suggesting, despite the austerity of environment, the chandeliers Perrault might have given Aurora’s palace. The scene is subtly and eloquently lighted by Mark Stanley (who surely deserves a MacArthur of his own).

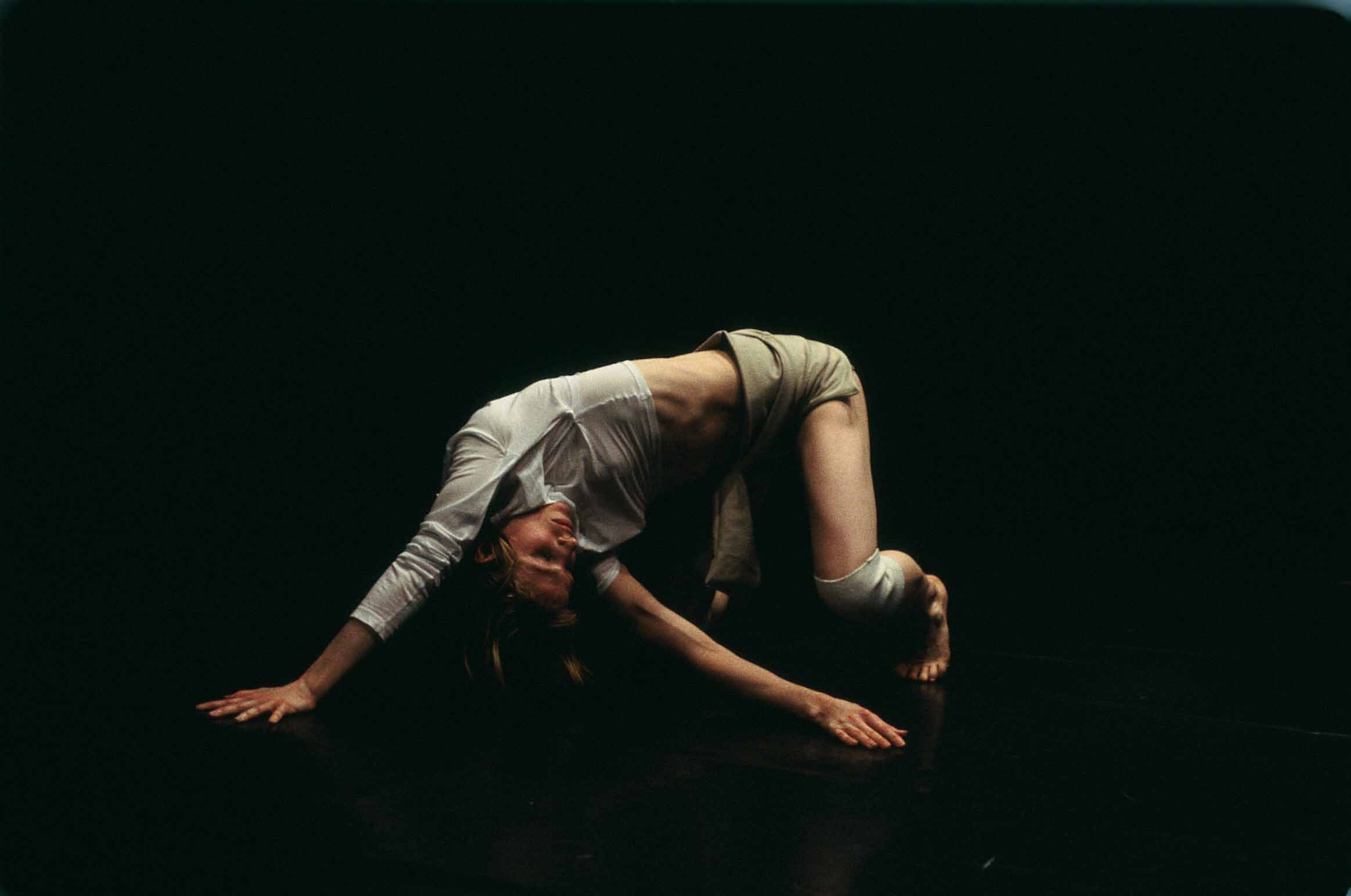

The focal point of the choreography is a young woman, the pale, grave-faced, Kristin Hollinsworth, distinguished for her long-limbed flexibility and grace. Surrounding her is the small crowd one might call family or society. Movement motifs define the girl’s difference and strangeness: Her arms and legs stretch, oddly angled, as if to shield her from view or point to a faraway nowhere; her whole body, held off-kilter, falls into fits of stasis as if she were absorbed in a dream. She is luminous in her isolation, and inscrutable. (Doesn’t this lie at the heart of being a princess—remaining aloof and apart from the ordinary run of humankind?) The crowd insists upon making her one of them.

The focal point of the choreography is a young woman, the pale, grave-faced, Kristin Hollinsworth, distinguished for her long-limbed flexibility and grace. Surrounding her is the small crowd one might call family or society. Movement motifs define the girl’s difference and strangeness: Her arms and legs stretch, oddly angled, as if to shield her from view or point to a faraway nowhere; her whole body, held off-kilter, falls into fits of stasis as if she were absorbed in a dream. She is luminous in her isolation, and inscrutable. (Doesn’t this lie at the heart of being a princess—remaining aloof and apart from the ordinary run of humankind?) The crowd insists upon making her one of them.

Together the two camps, Herself and The Others, perform the activities of rehabilitation. Again and again, the girl’s often unresponsive body is positioned into the anatomical positions that mean contact (even the small interactions so-called normal folks take for granted), communication, lust and its aristocratic cousin, love. Occasionally the girl initiates the exercises herself; sometimes her would-be rescuers, losing patience, bully her into the process; otherwise the action, even when physically fraught, exudes a clinical serenity. Whatever the emotional atmosphere, the result is always the same. The girl’s body halts; passive and flaccid, it drops from her would-be helpers’ arms. As both sides give up for the moment, the girl moves away with an air of a hurt bafflement, retreating into her chamber of living death. (Once in a while, though, there’s a flicker of stubbornness about her response, a glimpse of the madman’s will to persist in his madness because it constitutes his only security.) Inevitably, heroically, both sides keep coming back for another go.

The saddest thing about the circumstances Marshall depicts is that the afflicted girl seems (though only seems, and only intermittently) to want to join in the flow of common life, to be part of a social world, to connect. But, despite repeated effort, both heartbreaking and exasperating in its futility, she can’t—and both she and the people concerned with her plight are doomed to not knowing why. Or is the saddest thing, after all, the fact that, increasingly as the piece progresses, the crowd reveals itself to be simply a collection of people like the girl, the difference in their condition being merely one of degree, not kind? In the closing image, both heroine and nameless crowd, the ostensibly maimed and the ostensibly whole, lie outstretched on the ground, rolling back and forth in a horizontal line, like wind-whipped ocean waves in an eternity of sameness.

Other Stories, the companion piece to Sleeping Beauty, is dutifully joined to its partner on the program by its opening image: a woman’s body lying supine on a raised plinth, illuminated by a glaring shaft of light on an otherwise dark stage. But the piece quickly moves on to its own concerns, revealing, in edgily fragmented sightings, seven hyperactive characters in search of an auteur to provide them with one of drama’s basic necessities: narrative—or at least dilemma, or at the very least situation.

As it is, they’re merely fugitives from the stage that is perennially set for dreams when we sleep, or perhaps the lurid personae that spring from the synthetic sleep of anesthesia (think of the old term “operating theater”), or souls lost in the outtakes of a movie doomed to failure from the start. Their antics—shards of high (melo)drama, surreal opera, and vaudeville, along with the frantic chaos invariably attendant on theatrical enterprises—seem to go on for a century, gradually relinquishing their right to our attention. I think the piece is supposed to be funny, and the opening night audience did chortle cooperatively a few times, but Marshall, who has a look of Garbo about her, doesn’t laugh with confidence or ease.

The one terrific thing about Other Stories is the costuming, by Kasia Walicka Maimone, who has served Marshall long and well, but usually, as in Sleeping Beauty with subdued lyricism. Here the costumes are a medley of wildly fanciful finery borrowed from the worlds of princess, slut, and itinerant entertainer—garb for a poetic Hallowe’en.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

SNAKE EYES

Merce Cunningham Dance Company / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, New York City / October 14-18, 2003

Dancing usually hangs out with music—and with good reason. Think rhythmic, structural, and atmospheric support. Think Tchaikovsky-Petipa; think Stravinsky-Balanchine. Merce Cunningham, celebrating the 50th anniversary of his company at BAM this week, was a pioneer in disconnecting the two arts, inviting them to exist in the same place and time yet avoid co-dependency.

With avant-garde practitioners like John Cage, Cunningham evolved the policy of commissioning composers to provide a score of a specific duration (giving them no other parameters or clues to his own intentions), while he created choreography of the same length. Music and dance met only on opening night of the production. So it was not entirely astonishing to learn that a pair of forward-leaning rock bands, Radiohead and the Icelandic Sigur Rós, would provide the sound for Cunningham’s newest work, Split Sides, the ostensible climax of an event-filled anniversary year, though the choreographer usually goes for more highbrow types. But rock commands an audience and BAM, like any other producing organization, needs to sell tickets.

It should be mentioned here that the use, in productions featuring contemporary choreography, of musical and visual artists who will attract their own crowd to the performance is nothing new at BAM. Indeed, this shrewd blend of avant-garde elements, historically related to holes in the wall, with astonish-me spectacle has been a regular practice of the house’s Next Wave series since its inception in 1983. Some of the combinations have been truly organic, the happiest, perhaps, being the teaming of Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, and Lucinda Childs for Einstein on the Beach. Others have been contrivances with an opportunistic air. Fortunately, in Cunningham’s case, given the persistent integrity of his work and his personal dignity (a mix of modesty, piercing intelligence, and wit), nothing the man is involved in looks cheap or merely canny.

Nevertheless, in addition to the musical choice made regarding Split Sides, other aspects of the dance’s construction turned venerable Cunningham practices into publicity stunts. Most important was the roll of the dice, an I Ching practice that allows chance, through its random effect, to enlarge one’s sphere of action beyond the narrow, prejudicial dictates of personal choice. For the 40-minute Split Sides, Cunningham created a pair of 20-minute dances and ordered up two backdrops, one each from Robert Heishman and Catherine Yass, and two sets of costumes and lighting plots, from company regulars James Hall and James F. Ingalls, respectively. A roll of the dice before each performance would dictate the order in which the elements were used in the two-part piece. If all the journalism this adventure generated could be turned into a $100 grant per word, Cunningham might never have to go begging again.

For the opening night gala, attended by a packed house of the rich, the famous, and the curious, augmented by squads of rock music fans and their Cunningham-reverent equivalent, as well as an extra component of security folks, the dice rolling was done onstage, in the presence of the musicians who would later be hidden in the pit and a few dancers picturesquely warming up. It featured New York’s Mayor Bloomberg at his most aggressively exuberant (to compensate for Cunningham’s decades of under appreciation?), with the rolling done by celebs like former Cunningham collaborators Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cunningham ur-dancer Carolyn Brown.

Eventually, after all the brouhaha, here it was, another Merce Cunningham dance, and this time, as chance would have it, not a particularly distinguished one. Following the dictates of the dice, the first segment used Part A of the choreography, Radiohead’s accompaniment, Heishman’s backdrop (like Yass’s, a pale blow-up of an abstract photo), and Hall’s black and white costumes (hyperactively scribbled-over unitards) as opposed to the ones aggravated with psychedelic tints; the second segment, the alternatives.

Neither sound score was what devotees of, say, Bach—favored by choreographers of various persuasions—would call music. Yet neither, though far less intellectually sophisticated than the work of, say, John Cage, was radically different, in effect, from the aural accompaniment Cunningham has traditionally provided for his dances. Hazard determined whether or not, at any given point in the proceedings, it meshed with the movement or served as a maddening distraction. Both Radiohead and Sigur Rós laid down a background of hypnotic New Age chimes-and-gongs (music to space out on), agitating it with the static of indecipherable speech, mechanical noise, and threats from nature (thunder, the buzz of swarming insects). Presumably the competing, fragmented sounds and rhythms reflected the contemporary mindset. To my ears—untutored in such matters, I grant you—all of it sounded terribly dated. Ignoring its hovering partner, the movement went serenely about its business.

Unfortunately, that business seemed to be a simplistic version of what Cunningham usually does—as if, having lured in a crowd unfamiliar with the sort of dancing he’s evolved in the last half century, he’d made his work more readily accessible. This friendly but artistically diminishing impulse was most evident in the structure department. Cunningham habitually composes long, flowing ensemble passages, streams of dance that seem capable of going on forever. Within these, an individual viewer is free to highlight, through his attention, the action of smaller groups. As if the choreographer had been reluctant to tax the patience of neophyte watchers, Split Sides makes a clear distinction between brief stretches of group movement decidedly reduced in complexity and solos, duos, trios, and so on that stand out—sharp and self-contained—like vaudeville turns. (The opening night crowd applauded several of them with relish.) What’s more, although Cunningham rarely dictates tone, there seemed to be several deliberately humorous patches—playful, even arch arrangements for twos and threes in which the dancers flirted and clowned like figures from some postmodern commedia dell’arte. I felt as if I were watching Cunningham 101, though that imaginary course would, more appropriately, consist of 20 minutes chosen at random from any of the choreographer’s masterworks and viewed in a state of calm receptivity.

For me, the treat of the evening was the 2002 Fluid Canvas, being given its New York premiere. In it, Cunningham’s 15 dancers, ravishingly lighted by James F. Ingalls, epitomize their breed. They’re a highly refined race noted for fluidity, fleetness, psychic as well as physical harmony in the most off-kilter positions, high alertness, and deep concentration. Several of the beautiful glimmering unitards—in gunmetal and aubergine—that James Hall designed for the piece are cut deep to the waist in back, and it was a surprise to see, not five minutes into the action, the gorgeously muscled flesh glistening with sweat, because the figures seemed superhuman creatures for whom effort was unnecessary.

The choreography makes much of unusual postures, sometimes with so much torque to them and such anti-intuitive arrangements of the arms, the dancers look like gargoyles—albeit extraordinarily handsome ones. At the same time, Cunningham allows the upper body to contradict its lower half, so that two very different kinds of activity are going on at once. These explorations do not so much refute classical ballet (which plays a much larger role in Cunningham’s resources than, say, the modern-dance inventions of Martha Graham, with whom once he danced) as they investigate, with a sympathetic curiosity, the reverse of its coin.

More typically of Cunningham—though more emphatically than usual—Fluid Canvas calls our attention to the varying numbers of dancers on stage at a given time. It also makes us acutely conscious of negative space. The voids created on the stage are as potent as the areas filled with human bodies carrying out a wide and subtle range of ever-shifting designs. Towards the end of the piece, the dancers sit hunkered over their own bodies, heavy and one with the earth, it would appear. Suddenly, they help each other up and rush swiftly, light as windswept autumn leaves, into the wings. Once they’ve vanished, the stage remains empty for a few seconds, just long enough to let the emptiness register, then the light is extinguished and the curtain falls. The dance isn’t over, Cunningham instructs us, until our eyes and minds take in the significant condition of not-dancing.

Photo credit: Jack Vartoogian: Daniel Squire and Holly Farmer in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

OZU MOVES

“Yasujiro Ozu: A Centennial Celebration” / Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater, NYC / October 4 – November 5, 2003

Dance aficionados as well as film connoisseurs will be drawn to the Walter Reade Theater for the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s “Yasujiro Ozu: A Centennial Celebration,” October 4 – November 5. The lure for the dance crowd? The iconic director’s insight into movement and his rendition – always sensitive and frequently sublime – of feelings that lie past the reach of words.

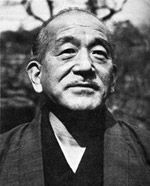

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing – an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period – extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties – once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing – an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period – extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties – once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Creating a peerless series of black and white “talkies” over two decades, Ozu probed the extraordinary ways in which limitation can serve to reveal the intangible (and most significant) aspects of existence, focusing the attention on essences rather than events. One of his most apparent means was stasis: minimal body and facial movement for the actors (emoting was thus precluded) and a fixed position for the camera, which then regarded the material before it like the unwavering eye of God. What is most curious about this denial of motion is the tremendous importance motion assumes when it does occur. Like that of very different masters – Balanchine, Ashton, and Tudor – Ozu’s “choreography” creates epiphanies by manifesting intense, unarticulated feeling through physical action. And it does so in remarkably varied ways.

In the 1953 Tokyo Story, as is typical of the mature Ozu, plot has become as fragile and translucent as a silver-penny petal. The film is dominated by a theme that obsessed Ozu throughout his career: the nature of human experience as it is expressed in the relationships between parents and their grown children.

An aging pair make a momentous visit to the big city where they find their adult offspring largely too preoccupied with their own concerns to give them the loving respect and attention one might assume to be a parent’s due. Resigned to their disappointment, they journey home, whereupon the mother succumbs to a stroke and lies unconscious on her deathbed. Ironically too late, the children gather in attendance around her pallet. Although charged with feeling, the scene – with the inert body at its center – is utterly quiet and self-contained. It’s almost a still life, the actors and the camera are physically so subdued.

The younger brother arrives after the others, explaining he’d been away on business when the summons came. He’s literally too late; while the camera gazed outward to the town, the sky, the river – the larger, sentient universe – the mother expired. By custom, her face is covered with a square of white cloth. “Look at her,” an elder sibling urges the latecomer, “she looks so peaceful.” The son moves to lift the cloth and, with typical Ozuian obliqueness, the camera – its rhythm as unforced and acutely timed as a sleeping child’s breath – cuts away. So we don’t see what the son sees – the mother’s placid face in death. We don’t need to. It already exists in our imagination. Nor do we see the son’s face; Ozu would consider even such a minor bit of melodrama tactless both emotionally and aesthetically. Instead, he slews the camera around to the other figures’ response, a kind of visual harmony to the unrecorded event. Kneeling, passive as hills, gazing down at their hands, they lift their heads to witness their brother’s sight, then, as one, incline slightly from the waist and neck, instinctively bowing to the sacredness of the moment.

This passage from Tokyo Story epitomizes the beauty and deftness with which Ozu makes his primary emotional point through a single move – the bow – in an environment of physical and emotional quiescence. In The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (1952), the climactic scene is based upon a journey – geographically minute and on domestic turf, poetically immense and structured as formally as a classical ballet. An estranged husband and wife, having reached the point of reconciliation, penetrate by stages into the core of their home, the kitchen. A modest room at the back of the dwelling, down several stairs, it fulfills a basic human need – hunger – yet this long-wed couple hardly knows where it is. (The erotic parallel is obvious, though it’s not in Ozu’s nature to belabor it.)

The husband is a simple man – blunt, good-hearted, tenaciously unaffected. His taste is for the common, unpretentious things of his background. They fit him, he explains at one point, later amplifying his observation: “It’s how a married life should be.” Superficially sophisticated, disappointed in the dullness of their union, his wife has rebuffed him for his lack of refinement. Now, having learned through pain to understand and appreciate each other, they celebrate by going in search of a midnight bowl of rice doused in green tea – a peasant meal, typically consumed with slurping relish.

The kitchen is hidden, almost unknown, territory to this comfortably-off pair, but to preserve the intimacy of their newfound accord, they choose not to summon their sleeping maid to serve them. Side by side, touching each other so lightly and unemphatically, their physical contact is barely visible, they slide back the wall panel of their living room, pass through a narrow, dimly lit corridor, slide open yet another panel, and illuminate a primitive hanging lamp that discloses the humble kitchen so mysterious to them. Together, they prepare their repast – he gently draws back her kimono sleeve as she washes her hands – and return by the same route, soft-edged shadows on the translucent panels they shut behind them.

Their journey – with its unstressed sexual parallel – is one of venturing by degrees, of lifting veils and entering uncharted passageways. As it progresses, the bourgeois environment and the bourgeois situation dissolve into evocations of legendary quests: Orpheus descending into the underworld in search of Eurydice, the prince of Perrault’s Sleeping Beauty crossing the barriers that separate him from his heart’s desire.

Late Spring, made in 1949 and perhaps Ozu’s most exquisite achievement, uses an image of nature in motion to express human feeling. The tale – again, one that Ozu reiterated as if he could never be done with the issue – concerns a widower who realizes he must release his beloved and devoted daughter from tending him into a life of her own. She’s reluctant to leave the serene, secure shelter of her girlhood, so he deceives her into thinking she must marry because he wants to remarry. The idea of her father’s entering into a sexual alliance after her mother’s death revolts the young woman. Matters come to a crisis at a Noh performance, when the daughter sees her father exchange gazes with the lovely widow who will presumably appropriate her place.

This being an Ozu film, not a word is spoken directly about the matter, but the daughter’s swiftly mounting feelings of anger and desolation are clear, almost unbearable in their repressed intensity. The theater scene ends and, as is Ozu’s custom in shifting locale, a landscape shot is inserted. Technically, it’s a transitional device; aesthetically, it’s a container for human emotion so dense and many-faceted it can’t be particularized. Several such shots, earlier in this film, showed a few thin, barren tree trunks. Now Ozu’s camera looks up at a flourishing tree, proudly set against the blank sky. At the peak of its maturity, the tree is wide and thickly branched, in full leaf. A wind blows through it, making its foliage dance in the sunlight, as if to emphasize its vitality, and its already luxuriant expanse seems to inflate, like a lung. The tree – whether you take it to be just a tree or a symbol of unquenchable, continuing life – is breathing. The breath is the breath of immanence.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

BACK STORY

This week’s performances of Ballett Frankfurt at the Brooklyn Academy of Music mark a critical stage in the career of William Forsythe, who has shaped the company according to his singular aesthetic. I’ve invited the dance writer Roslyn Sulcas, our New York expert on Forsythe, to provide some background. Here is her report:

William Forsythe has been quietly enlarging the world of classical dance over the last two decades. Born in New York, and trained at the Joffrey Ballet School, Forsythe moved to Germany in his early twenties to join the Stuttgart Ballet and has lived there ever since. Although he has been a major presence on the European dance scene since Rudolf Nureyev commissioned In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1987, it is only during the last few years that he has become better known to an American dance public, as companies nationwide have acquired works like In the Middle, Herman Schmermann, and The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude.

More frequent tours to New York in recent years have also meant that Forsythe has been able to show in greater depth the elaborate movement vocabulary that he and his dancers have developed during his tenure in Frankfurt, alongside the inventive theatricality and creative use of lighting that characterize his work. Even if it often strays from ballet’s emphasis on lengthened line and effortless virtuosity, much of Forsythe’s work is engendered by the ideas present in the forms of classical dance. It also looks balletic because he uses classically trained dancers, whose bodies instinctively enact the formal rules (turn-out of the hips, pointed feet, the extension of the spine and limbs, epaulement) that characterize the art form, even as they deploy it in unconventional ways.

The result is dance that (among other things) disregards the vertical planes to which the classical positions of the body are fixed, uses the thrust and momentum of the dancer’s weight to alter conventional transitions between steps, deploys the upper body to generate movement rather than accessorizing the legs, and offers a complex display of coordination and counterpoint.

Sadly, the ensemble with which Forsythe has developed this distinctive vocabulary and a huge repertoire of dances will cease to exist as of June next year. The reasons for the company’s dissolution remain somewhat murky. In early summer last year, rumors circulated that a newly politically conservative Frankfurt city council, which funds the company as part of the Frankfurt Opera ensemble, was reluctant to extend Forsythe’s current contract past its expiration date of June 2004, preferring to re-establish a more conventional ballet company in the city and hoping to cut costs on an increasingly beleaguered cultural budget. (An illogical idea, if true, given the even greater expense of running a conventional ballet company.) After the media seized upon the news, thousands of e-mails and faxes from all over the world, protesting this decision, poured into the mayor’s office, prompting a statement that there was no intention to fire Forsythe. By then, however, Forsythe had decided that he didn’t want to go on in an atmosphere that was hostile to his work. (Subsequently, the city council announced that Ballett Frankfurt could continue if the budget was cut by 80%.)

The dissolution of Ballett Frankfurt is of great consequence to the dance world. Over two decades, Forsythe transformed this company into one of the most consequential contemporary ballet ensembles in the world, creating dances out of a profound body of deeply ingrained physical knowledge. Choreographers need their tools – dancers – and the best tools are those who have been honed into perfect form for the work at hand. Forsythe will, of course, continue to be sought after as a dance maker, and will no doubt go on to make important pieces; there is talk at present of his forming a smaller company that would be partially funded by the states of Saxony and Hesse. Nonetheless, those twenty years’ worth of ballets, the heritage present in the collective body of dancers, is a significant loss to the world of dance, and well beyond.

© 2003 Roslyn Sulcas

AFTER THE FACT

Ballett Frankfurt / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / September 30 – October 5, 2003

I wish I liked William Forsythe’s work more. After Ballett Frankfurt’s opening night at BAM, I felt an inch closer to appreciating it – as the enthusiastic audience, peppered with dance-world celebrities, clearly did. But no more than an inch. Yes, the vocabulary is inventive (if narrow). The pictorial sense at work is superb. The Forsythe-groomed dancers perform with extravagant energy and commitment. But the dances seem to be telling the same story over and over again – or no story at all. You watch these creations and nothing happens to you. (For “you,” read “I” and “me.”) This choreography doesn’t galvanize my feelings; it leaves my perception of the universe intact. I walk out of the theater exactly the same person I was when I walked in. “I just don’t get it,” complained one of my colleagues in the second intermission, waving his hand toward the stage as if to indicate the whole Forsythe oeuvre. But he and I are in the minority.

Forsythe calibrated his program – perhaps Ballett Frankfurt’s farewell to New York – astutely. Two largish group pieces framed a pair of chamber-scaled works, a women’s duet and a male quartet, the public encasing the intimate. Austere elegance governed the overall effect. Minimal music, provided by Forsythe’s regular sound man, Thom Willems, or silence broken only by the dancers’ emphatic breathing accompanied lush, high-voltage dancing. The “scenery” consisted merely of black drops, in heavy velvet or translucent gauze. The costuming alternately reflected dancers’ practice clothes and pajama-casual schmattes – the antithesis of fancy dress that’s almost a moral stance these days. Talk about suave!

The Room As It Was served well as a curtain raiser since it presents Forsythe at his most typical. Eight dancers come and go, working in ever-shifting small groups or as loners tangentially connected to the “crowd.” Hyperactivity – strikingly, in the torso and pelvis as well as the arms and legs – contrasts with slow swirls that twist off the vertical to spill, still writhing, into horizontal positions on the floor. Small vortexes of motion occur constantly. Sometimes they’re charged with a little feeling, even a little drama; more often they look like calculated investigations into the possibilities of the human anatomy.

Images fleetingly suggesting confrontation and combat interlace with tentative, solicitous handholds, as if the participants had joined an encounter group and were sensitively trying to figure out how to get along with one another. Shards of disaffection and absurdity à la Pina Bausch surface too, as in a sequence where a fellow repeatedly attempts to plant a gentle kiss on the neck of an indifferent young woman who doesn’t even bother to repulse him but merely deflects his efforts as she waits impatiently for a better offer.

Though the piece is very bright and busy, it doesn’t make a dent in your consciousness until its very last moments, when a mid-stage scrim rises, doubling the depth of the available space and revealing a pair of dancers in shadow. A fragment of music is heard; it seems to announce that the show has now begun.

(N.N.N.N) – Forsythe goes in for abstruse titles – uses lots of gestures that lie (in the middle, somewhat elevated, you might say) between pantomime and dancing. When the full cast of the piece – four guys – is involved, clustered tight, with no music to help out, timing becomes a tour de force. The imagery borrows from sports, martial arts, artificial respiration, and just plain goofing around. Fighting and bonding, Forsythe seems to be saying, that’s what men do, and the clue to their nature is that they do it simultaneously. Unfortunately, on this occasion, they do it for far too long. The extended proceedings begin to look aimless because, unlike Merce Cunningham – the master of going on at length without many clues to mark where we are, where we’re heading, and what’s happening en route – Forsythe can’t make us confident that his choreography harbors an internal structure, albeit a hidden one.

In Duo, Forsythe shows us what women do – understand the aspects of life that can’t be seen or explained and, via this intuition, become one with the inner workings of the world. Although it has its share of Forsythian middle-of-the-body wriggles and slews off the vertical, the movement language of this duet emphasizes long stretched limbs, diagonalled arms suggesting the hands of a clock, the swing of a pendulum. Moments of stasis, alternating with calmly paced action, lend the bodies a sculptural effect and, with that, an emotional dimension. The women seem to be allying themselves with passing time, mastering it by giving in to it.

Women can also, Forsythe observes as a footnote, dress to kill. And he has dressed this voluptuously bare-legged pair in shiny black bikini briefs, veiling their torsos and arms with the sheerest imaginable jet stretch fabric, so that the top of the body appears naked but glamorously shadowed. Having noted what a sheath of see-through black stocking can do for the leg, he made the imaginative leap to what it might do for breasts.

One Flat Thing, reproduced, used as the program’s closer, is unabashedly based on a gimmick: It opens with fourteen dancers aggressively rushing forward, pushing before them large utilitarian tables that, arranged in an uncompromising grid, nearly fill the stage. They proceed to dance on top of them, underneath them, and in the stingy spaces left between them. The effect is that of humanity alive and kicking despite a world that has almost no space – space being to dancers as essential as air. Inevitably, the whole business is ridden with clichés: The tables become autopsy slabs, coffins, and the like; dancers not engaged at a given moment stand at the back of the space in a twilight of inaction, staring, expressionless, at the audience.

The piece is almost unwatchable, partly because, as with (N.N.N.N), its structure is ill-defined. Between the initial attack of the tables and their withdrawal, which closes the dance, the activity seems to occur almost at random, utterly even toned, threatening to go on forever, giving the viewer far too much time in which to ask, “What’s this about?” Are we watching teenagers rampaging in their high school cafeteria or yet another one of those apocalyptic affairs art is prone to? Both maybe, and in both the spirit of Jerome Robbins seems not very far away.

Thinking about these works in retrospect as I was writing about them, I found more in them to admire than I did when I was watching them. Is this because a central aspect of Forsythe’s choreography is conceptual rather than visceral? I must say I’ve always been leery of choreography that appeals more as idea than as dance.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias