Peter Boal: “The business of being a prince is not a look. It’s not an action. It’s a model. It’s the supreme example of how to behave in life.” Village Voice 3/10/04

PUPPET SHOW

Paul Taylor Dance Company / City Center, NYC / March 2-14, 2004

Paul Taylor’s current two-week run at the City Center reveals the company in splendid form, dancing as if an ardent, intensified study of echt Taylor style had reanimated it. Old and recent masterworks-Aureole, Airs, Piazzolla Caldera, Promethean Fire-look reborn. And you can spend an enchanted evening focusing on any one of three stellar women: the veteran Silvia Nevjinsky, who has acquired a new softness, calm, and sculptural dimension; Annmaria Mazzini, who follows in the line of Ruth Andrien and Kate Johnson as the girl everyone adores; and Michelle Fleet, a more recent addition to the troupe, who is instantly recognizable as the Next Great Thing. The fact that the two new choreographic offerings were non-events-flops, to put it bluntly-is almost beside the point.

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine’s Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky’s pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine’s libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine’s characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely-Taylor’s plot being improbable and pointless-to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor’s pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master’s tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine’s Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky’s pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine’s libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine’s characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely-Taylor’s plot being improbable and pointless-to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor’s pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master’s tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Taylor’s Emperor, dressed in a jet version of Napoleonic uniform, may be Fokine’s Charlatan, earning a living by displaying his puppets (just possibly human slaves) to a cruel audience in the market square. On the other hand, he may be: God; the autocratic Diaghilev; the founder-leader of a dance company that exists to dance that great master’s choreography (Taylor himself, perhaps); or one or another of the powerful guys dominating the news of late, who operate according to the conviction that they have the right to control how people should live (and die).

Such a puppeteer may be even worse than evil. Writing of his retirement from performing after chronic physical woes caused his collapse on stage, Taylor notes in his autobiography, Private Domain, “Once in a while it seems sad, but most times it seems comical. Our dance god, the Great Puppeteer up there in the flies, that ineffable string snipper, turned out to be an old-time prankster.”

The best thing in this excursion is the figure of the Puppet, played soulfully by Patrick Corbin, who evokes the photographic evidence of Nijinsky’s portrayal of Petrushka. Costumed in white, like a commedia dell’arte clown, Corbin is pitiably limp and disjointed, fatally pure and innocent. Taylor’s cleverest move in this piece is to have the Puppet led around, often dragged, on a long-reined leash attached to a noose-like collar. The initiated will recall another character on display in Fokine’s crude, raucous marketplace-the trained bear.

Taylor’s riff on Fokine also includes a subterranean stream of comment on homosexuality. It takes the form of the misalliance of the fop in lavender regalia and the Emperor’s minxish daughter as well as the daughter’s cavorting with her soldier paramour, not simply for their mutual lustful pleasure but to torment the Puppet. Balletomanes will recall the fact that Nijinsky was Diaghilev’s lover for a time, before a conniving woman came between them. Still, all the diverting speculation about who represents what in Le Grand Puppetier fails to conceal the fact that nothing interesting is going on dancewise.

A second new work, being given its local premiere, fared no better, though it was more fun. “In the beginning,” as the Good Book tells us, “God created the heaven and the earth.” For In the Beginning, his own typically idiosyncratic account of Creation and its consequences, Taylor takes a Classic Comics view, rendering the proceedings with simplistic, amusing charm. For musical accompaniment he’s borrowed from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana (of all things!) and Der Mond. Santo Loquasto has provided him with natty Middle Easternish costumes and a series of backdrop projections in childlike style of the relevant geography, fruit trees, doves, and rainbow (though the choreography supplies neither ark nor flood).

Taylor’s Jehovah starts out as an Old Testament God, a strict parent who, having created the human race, is prone to rage at its inevitable transgressions. Then, with a quick shift of wardrobe from black to white, as the piece skips blithely to literature’s greatest sequel, he (He, if you will) evolves into an icon of forgiveness. The hands that were all wrathfully pointing fingers now relax to deliver blessings from palm to gratefully bowed heads.

Adam and Eve are multiples. Taylor, no mean creator himself, produces no fewer than four of each, with a matching plethora of apples. A fifth woman, listed in the program as an Eve, turns out to be Lilith, apocryphal but tempting as hell, who relishes her job of luring the others into an orgy of group sex. Their paradise lost, naked and ashamed, scared and sorrowful, our first ancestors produce a horde of offspring. (Well, how else would the world have been peopled?) With the agonies of childbirth duly documented-in caricature mode, of course-Cain and Abel pop out first. In a matter of seconds, these large, hairy neonates go from fetal position to thumbsucking to a sibling rivalry that begins in normal boys-will-be-boys roughhousing and ends (as you may have heard), very, very badly.

Finding nothing more pertinent to do, the rest of the population engages in some innocuous Israeli folk dancing, at which point Jehovah reappears. It being in his job description, he throws an irate-power tantrum strangely reminiscent of some megalomaniac solos in the repertory of the redoubtable Martha Graham, with whom Taylor once danced. Chastized, humanity duly wanders, faltering, in the desert-in a crossover before a thorny front cloth. And then-by some theatrical or spiritual miracle that leaves you saying “huh?”-the beleaguered wanderers find themselves reinstated in God’s grace. As a curtain line, the tableau seems premature.

Taylor has done terrific work before with stock stories-in the 1983 Snow White (which boasts an unforgettable apple) and the 1980 Sacre du Printemps-and, indeed, with Bible stories, as in that crazily ambitious failure, the 1973 American Genesis. In the Beginning shows little evidence of ambition, just as it yields little rigor, little substance, and little resonance. But if this piece is slim, it’s still entertaining-silly and touching by turns, with brief moments and maverick insights that furnish clear evidence of genius.

Photo credit: Paul B. Goode: Members of the Paul Taylor Dance Company assembled for Taylor’s Le Grand Puppetier

2004 Tobi Tobias

Paul Taylor Dance Company / City Center, NYC / March 2-14, 2004

Paul Taylor’s current two-week run at the City Center reveals the company in splendid form, dancing as if an ardent, intensified study of echt Taylor style had reanimated it. Old and recent masterworks—Aureole, Airs, Piazzolla Caldera, Promethean Fire—look reborn. And you can spend an enchanted evening focusing on any one of three stellar women: the veteran Silvia Nevjinsky, who has acquired a new softness, calm, and sculptural dimension; Annmaria Mazzini, who follows in the line of Ruth Andrien and Kate Johnson as the girl everyone adores; and Michelle Fleet, a more recent addition to the troupe, who is instantly recognizable as the Next Great Thing. The fact that the two new choreographic offerings were non-events—flops, to put it bluntly—is almost beside the point.

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine’s Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky’s pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine’s libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine’s characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely—Taylor’s plot being improbable and pointless—to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor’s pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master’s tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine’s Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky’s pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine’s libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine’s characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely—Taylor’s plot being improbable and pointless—to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor’s pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master’s tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Taylor’s Emperor, dressed in a jet version of Napoleonic uniform, may be Fokine’s Charlatan, earning a living by displaying his puppets (just possibly human slaves) to a cruel audience in the market square. On the other hand, he may be: God; the autocratic Diaghilev; the founder-leader of a dance company that exists to dance that great master’s choreography (Taylor himself, perhaps); or one or another of the powerful guys dominating the news of late, who operate according to the conviction that they have the right to control how people should live (and die).

Such a puppeteer may be even worse than evil. Writing of his retirement from performing after chronic physical woes caused his collapse on stage, Taylor notes in his autobiography, Private Domain, “Once in a while it seems sad, but most times it seems comical. Our dance god, the Great Puppeteer up there in the flies, that ineffable string snipper, turned out to be an old-time prankster.”

The best thing in this excursion is the figure of the Puppet, played soulfully by Patrick Corbin, who evokes the photographic evidence of Nijinsky’s portrayal of Petrushka. Costumed in white, like a commedia dell’arte clown, Corbin is pitiably limp and disjointed, fatally pure and innocent. Taylor’s cleverest move in this piece is to have the Puppet led around, often dragged, on a long-reined leash attached to a noose-like collar. The initiated will recall another character on display in Fokine’s crude, raucous marketplace—the trained bear.

Taylor’s riff on Fokine also includes a subterranean stream of comment on homosexuality. It takes the form of the misalliance of the fop in lavender regalia and the Emperor’s minxish daughter as well as the daughter’s cavorting with her soldier paramour, not simply for their mutual lustful pleasure but to torment the Puppet. Balletomanes will recall the fact that Nijinsky was Diaghilev’s lover for a time, before a conniving woman came between them. Still, all the diverting speculation about who represents what in Le Grand Puppetier fails to conceal the fact that nothing interesting is going on dancewise.

A second new work, being given its local premiere, fared no better, though it was more fun. “In the beginning,” as the Good Book tells us, “God created the heaven and the earth.” For In the Beginning, his own typically idiosyncratic account of Creation and its consequences, Taylor takes a Classic Comics view, rendering the proceedings with simplistic, amusing charm. For musical accompaniment he’s borrowed from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana (of all things!) and Der Mond. Santo Loquasto has provided him with natty Middle Easternish costumes and a series of backdrop projections in childlike style of the relevant geography, fruit trees, doves, and rainbow (though the choreography supplies neither ark nor flood).

Taylor’s Jehovah starts out as an Old Testament God, a strict parent who, having created the human race, is prone to rage at its inevitable transgressions. Then, with a quick shift of wardrobe from black to white, as the piece skips blithely to literature’s greatest sequel, he (He, if you will) evolves into an icon of forgiveness. The hands that were all wrathfully pointing fingers now relax to deliver blessings from palm to gratefully bowed heads.

Adam and Eve are multiples. Taylor, no mean creator himself, produces no fewer than four of each, with a matching plethora of apples. A fifth woman, listed in the program as an Eve, turns out to be Lilith, apocryphal but tempting as hell, who relishes her job of luring the others into an orgy of group sex. Their paradise lost, naked and ashamed, scared and sorrowful, our first ancestors produce a horde of offspring. (Well, how else would the world have been peopled?) With the agonies of childbirth duly documented—in caricature mode, of course—Cain and Abel pop out first. In a matter of seconds, these large, hairy neonates go from fetal position to thumbsucking to a sibling rivalry that begins in normal boys-will-be-boys roughhousing and ends (as you may have heard), very, very badly.

Finding nothing more pertinent to do, the rest of the population engages in some innocuous Israeli folk dancing, at which point Jehovah reappears. It being in his job description, he throws an irate-power tantrum strangely reminiscent of some megalomaniac solos in the repertory of the redoubtable Martha Graham, with whom Taylor once danced. Chastized, humanity duly wanders, faltering, in the desert—in a crossover before a thorny front cloth. And then—by some theatrical or spiritual miracle that leaves you saying “huh?”—the beleaguered wanderers find themselves reinstated in God’s grace. As a curtain line, the tableau seems premature.

Taylor has done terrific work before with stock stories—in the 1983 Snow White (which boasts an unforgettable apple) and the 1980 Sacre du Printemps—and, indeed, with Bible stories, as in that crazily ambitious failure, the 1973 American Genesis. In the Beginning shows little evidence of ambition, just as it yields little rigor, little substance, and little resonance. But if this piece is slim, it’s still entertaining—silly and touching by turns, with brief moments and maverick insights that furnish clear evidence of genius.

Photo credit: Paul B. Goode: Members of the Paul Taylor Dance Company assembled for Taylor’s Le Grand Puppetier

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Cherylyn Lavagnino Dance

Lavagnino uses [pointe work] not as the extension it is of classical ballet’s svelte, codified vocabulary, but with deliberate perversity, as if the capability were a bizarre twist of nature. Village Voice 3/1/04

SCENTS & SENSIBILITY

“Fashioning the Modern Woman: The Art of the Couturière, 1919 – 1939” / The Museum at FIT, NYC / February 10 – April 10, 2004

“Temptation, Joy & Scandal: Fragrance & Fashion 1900-1950” / The Museum at FIT, NYC / February 24 – April 10, 2004

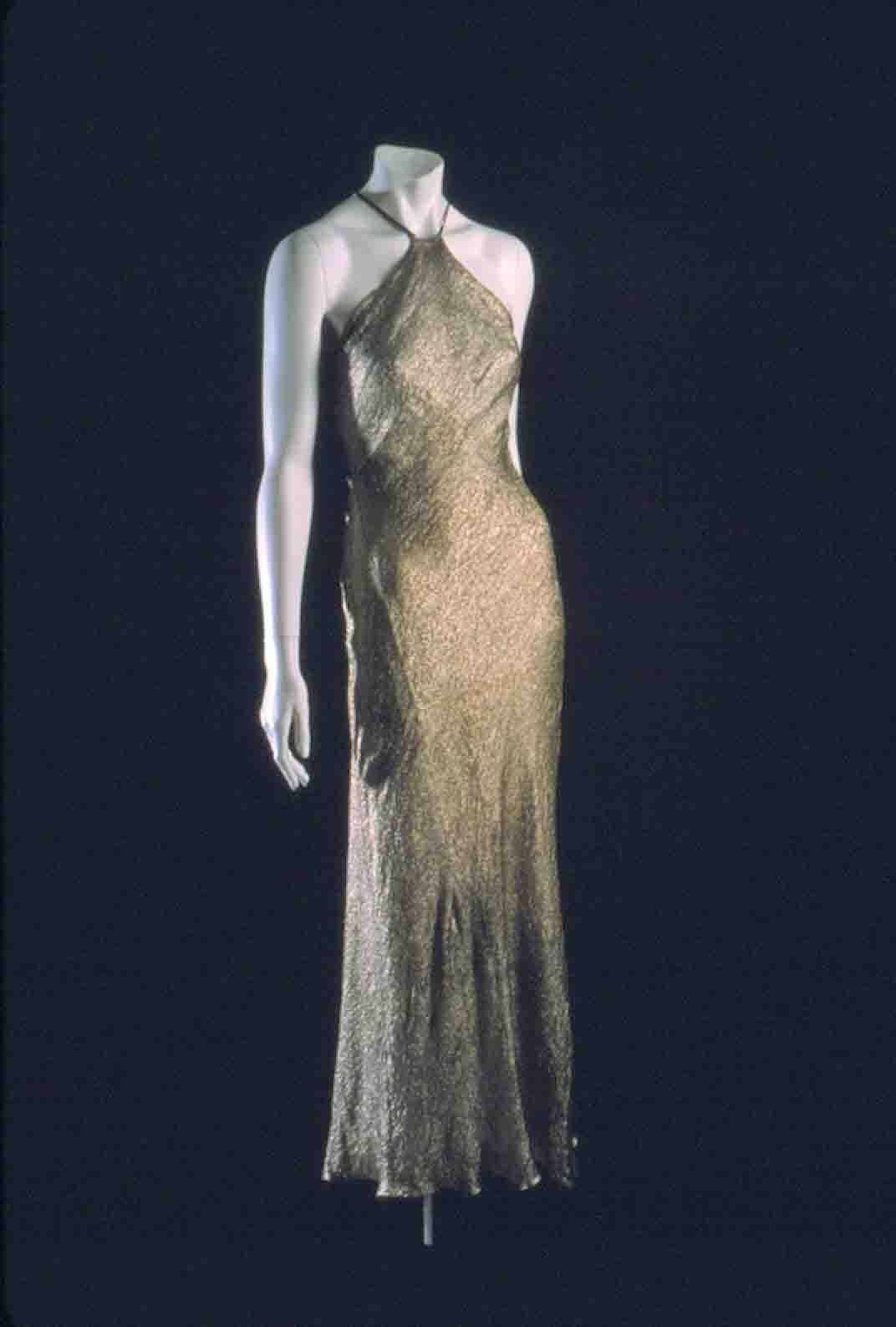

Valerie Steele’s argument is couldn’t be simpler. In the two-decade period between the World Wars (1919-1939), she points out, couturières, not couturiers—gals, not guys—dominated the field of designing for women. Before that, males held sway, as they have ever since. “Fashioning the Modern Woman,” the pleasurable exhibition Steele has curated for the Museum at FIT, reveals the depth, richness, and calm self-confidence of women’s achievement in this halcyon period. It does so with minimal supporting text and no theoretical fanfare whatsoever, but simply by offering up the primary evidence—garment by garment, the individual pieces chosen with sharply honed taste and then tellingly juxtaposed.

Represented here are the names everyone knows: Chanel, Schiaparelli—and then singular talents who are not quite household words, Madeleine Vionnet, Jeanne Lanvin, and Alix Grès. Others are familiar only to historically minded devotees of costume, among them the pair with conjoined names, Augustabernard and Louiseboulanger; Jeanne Paquin; Maggy Rouff; and the sister teams of Callot and Boué, whose collaborations might be the stuff of fairy tales. (The Boués called their house fragrance Quand les Fleurs Rêvent—When Flowers Dream.) And there are some about whom almost nothing is known, though their designs survive, bearing witness to their gifts.

Trace the winding path in the larger of the two rooms devoted to the exhibition (the entry chamber offers a historical prologue), and you encounter a parade of elegant, often innovative dresses and gowns, not one of them outlandish, each capable of transforming its wearer into a piece of poetry. If you can wrench your attention away from the sheer beauty and understated luxe of the display, you’re bound to be impressed by the element of conceptual invention.

A quartet of Augustabernard dresses from the early Thirties—one for day, three for evening—is an exercise in simplicity, at once adamant and lovely. It limits its collective palette to pale dusky peach (the hue changing according to the reflective differences between satin and crepe), matte black, copper, and a plum to which velvet lends added lushness. Like Vionnet, Augusta Bernard was a master of the bias cut, and her creations, fashioned for a willowy figure, drape as if nature allied them to the female anatomy. The dresses cling here, expand into a vertical column of fluid ripples there, giving a poignant delicacy to the figure, especially at the collar bone, the exposed shoulder blades, and the boyish hips. The hems are uneven, descending in back to make the faintest suggestion of a train—the sign, perhaps, of a princess in exile. The aggressive print of the day dress (at a distance it suggests hound’s-tooth check) is a wry joke, since the fabric is fine and the draping a marvel of lyric grace, while a little flourish of fabric at one shoulder looks like a cross between an epaulet and an angel’s wing.

The parade of 15 Chanels alone will make you want to set fire to your closet and will reveal to all but the most erudite costume aficionado a heretofore unappreciated range of the woman’s genius. Chanel’s concepts, as this display demonstrates, went far beyond the style tropes  for which she’s famous—and imitated. One example that held me in thrall was—is, it’s permanently burned into my imagination—a long black evening dress in which silk velvet, a fabric that manages to be dense and delicate simultaneously, describes a pinafore shape on the body. Inserts of fine-gauge black tulle, folded irregularly over flesh-colored material, are used for sleeves that stop, oddly, just above the elbow and for side panels at the torso, where the ribs house the lungs, as if these segments of the body had been exposed by x-ray. Velvet crops out again just beneath the shoulder, in a gathered flourish that cascades along the upper arms, like the petals of drooping flowers. The neckline plunges recklessly, and the back of the dress is slashed nearly to the waist, baring the spinal column. One imagines that, on a live woman (as opposed to a plaster mannequin), the vertebrae seemed to be transformed into eerie jewels. This is the sort of dress that makes you feel no other need exist.

for which she’s famous—and imitated. One example that held me in thrall was—is, it’s permanently burned into my imagination—a long black evening dress in which silk velvet, a fabric that manages to be dense and delicate simultaneously, describes a pinafore shape on the body. Inserts of fine-gauge black tulle, folded irregularly over flesh-colored material, are used for sleeves that stop, oddly, just above the elbow and for side panels at the torso, where the ribs house the lungs, as if these segments of the body had been exposed by x-ray. Velvet crops out again just beneath the shoulder, in a gathered flourish that cascades along the upper arms, like the petals of drooping flowers. The neckline plunges recklessly, and the back of the dress is slashed nearly to the waist, baring the spinal column. One imagines that, on a live woman (as opposed to a plaster mannequin), the vertebrae seemed to be transformed into eerie jewels. This is the sort of dress that makes you feel no other need exist.

A cluster of creations by Jeanne Lanvin almost equals the Chanels and is as eye-opening about the designer’s range. Though beautiful, much of Lanvin’s work seems bound to its time. Not so here. A trio of evening dresses, ankle-length and slim-lined, plays on the infinite possibilities possible in the manipulation of a mere three basic ingredients: black silk net, black silk tulle, and black paillettes (some square, some round). The resulting garments, playing on the contrast between translucent and opaque in costume’s most powerful hue, evoke seduction and armor, an inviting vulnerability and an arrogant glamour. Created in the early Thirties, these dresses would turn heads today even in the trendy restaurants and clubs of New York’s meat-packing district, where appearance is everything and the notion of chic is updated hourly.

My own taste leans to the simple and severe—to an emphasis on cut rather than adornment, to matte black rather than satiny pinks, but if it’s pretty you favor, there’s plenty of it here too: dresses that are effusions of poppies and roses; tributes to ancient Greece executed in metallic lamé; homages to the harem elaborated with beaded embroidery; even a handful of jeunes filles en fleurs affairs. In the hands of Vionnet, this last genre is treated so subtly, it achieves an immense sophistication, despite the sherbet tints.

Complementing this show is an exhibition rakishly titled “Temptation, Joy & Scandal,” with the subtitle “Fragrance & Fashion 1900-1950” to ground it. It was curated by FIT’s graduate students, but is no more an apprentice affair than the annual Workshop Performances of the School of American Ballet.

The modest available space has been transformed into a cave of dull-finish midnight blue that virtually swallows light. The soft, suggestive darkness is illuminated only so that a host of vitrines—poised so the visitor gazes not frankly at them but down into them—glow with their myriad scrupulously arranged treasures. Exquisitely fashioned bottles (collector’s items today) and their ingeniously contrived packaging gleam like Aladdin’s hoard, a medley of clear and etched crystal, burnished old gold, insouciantly painted flowers, and sleek stinging lacquers of Chinese red and implacable jet, here and there accented with turquoise and lapis lazuli. The show offers the requisite measure of scholarly reportage (and its excellent complimentary brochure, even more), but the presentation itself, aptly taking its cue from the nature of scent, is sheer enticement.

Photo credit: Irving Solero: (1) Madeleine Vionnet: Evening dress, silk lamé, c. 1938; The Museum at FIT, gift of Mrs. Rodman A. Heeren; (2) Gabrielle Chanel: Evening dress, black silk velvet and black silk chiffon, 1932-33; Museum of the City of New York, gift of Mrs. Harrison Williams

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Buglisi/Foreman Dance

The company [is] admirable for its insistence on live music and its terrific dancers, among them Christine Dakin, a paragon of experienced artistry, and the very young and altogether luminous Helen Hansen. Village Voice 2/25/04

BALANCHINE AT HOME #8: ORDER IN THE COURT

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

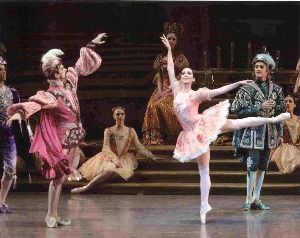

The Sleeping Beauty, that touchstone of classical ballet, addresses and illuminates several absorbing issues—among them, hierarchy. This is only natural. The work was created in 1890 in St. Petersburg. Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky, its composer, and Marius Petipa, its choreographer, lived and worked under the rule of the tsars. And classical ballet itself, in its training methodology and in the operation of the institutions that make it possible at its highest level of evolution, depends upon hierarchy—upon systematic development and the ordering of greater and lesser into a strong, self-confident whole.

The New York City Ballet’s production of Beauty—on display for two weeks to close the first half of the company’s Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration—is not by Balanchine, but by Peter Martins. Apart from its function of selling tickets—I hadn’t seen so many little girls assembled to witness a theatrical spectacle since I’d been to the ice show—it was included in the season to represent Balanchine’s heritage. The original Beauty was one of the glorious products of the Maryinsky Theatre, in whose academy the young Balanchine was bred.

The Sleeping Beauty proposes the court of the fictive King Florestan and his queen as a macrocosm, a hierarchical universe in itself. Attendants to the great are everywhere present in it. Beginning at the beginning—the christening of the royals’ infant daughter, Aurora—tiny, seemingly genderless pages bear the reigning monarchs’ trains, heads held high, chins thrust forward, feet busily working as they, probably first-year pupils in the company’s academy, progress in the adults’ footsteps. Soon slightly more substantial pages appear, bearing ornate cushions on which repose the gifts each of the fairies offers to the newborn princess. Just as a pair of nursemaids hovers over Baby Aurora, an octet of fairies-in-waiting accompanies the Lilac Fairy who will save, sustain, and bless the royal offspring’s life. Carabosse, the wicked fairy, is appropriately seconded by a team of jet-black insects who not only draw her carriage but also scuttle around her, metallic carapaces glittering, exuding, like a noxious fog, an atmosphere of fear and corruption. Even Little Red Riding Hood, one of the fairytale characters summoned to grace Aurora’s wedding, played by the most minuscule child imaginable, has a retinue of just slightly more robust children to play the trees of the forest that’s the scene of Perrault’s vulpine melodrama.

The Garland Dance, performed at the celebration of Aurora’s coming of age, is a veritable lesson in hierarchy. In the NYCB’s Beauty it is the one segment choreographed by Balanchine (after Petipa, of course). Here 16 pairs of adult men and women—their costumes executed in garden tints and adorned with flowers—waltz in unison, manipulating stiff semi-circular hoops festooned with blossoms. As soon as their charm has registered, they’re joined by 16 little girls with flexible flower chains that evoke the tender new growth trees sprout in spring. Eventually eight adolescent-looking girls are added to the picture, and the stage becomes a strictly organized floral tapestry—the geometric patterning recalling the formal gardens of the seventeenth century—its design shifting kaleidoscopically. Beyond the sheer prettiness and ingenuity of the display lies a clear message about the scrupulously calibrated stages of growth through which a ballet pupil must move to attain even a first foothold (corps de ballet rank) in the company and the strength such an institution acquires through each of its members and aspirants having and knowing her place.

Throughout the ballet there are myriad examples (in the many soloist roles and principal parts) of the further stages possible in a dancer’s development as well as rich evidence of the variety of functions to which a dancer may be assigned (technical virtuoso, soubrette, character dancer, mime), according to his or her particular gifts.

Today’s audiences finds the neophytes—the bevy of diminutive Garland Dance girls in their floppy pink skirts—irresistibly cute, and indeed they are. I just wish the same viewers would take a moment to think about what these very young children represent—how poignant their commitment to their goal is in a world that now scorns the restrictions necessary to hierarchal order, how fragile and unpredictable the artistic future of each child is, and how necessary they all are to the continuity of their art form.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Jenifer Ringer as Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty (choreographed by Peter Martins, after Marius Petipa; Garland Dance choreographed by George Balanchine)

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Fugate/Bahiri Ballet NY

The troupe was at its ravishing best in two small masterworks of lyrical dancing—Antony Tudor’s serene Continuo,with its miraculous floating lifts, and George Balanchine’s Valse-Fantaisie, a windswept bagatelle that restores your faith in romance. Village Voice 2/13/04

Jody Oberfelder Dance Projects

Many of the solos, duets, and small-group vignettes that constitute [Landmarks of Dreams] have a colorful, playful air typical of a circus with theatrical aspirations, their vocabulary cheerfully mixing acrobatics, ethnic dance, and the ingenious cantilevering of contact improv. Village Voice 2/13/04

BALANCHINE AT HOME #7: DARLING

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

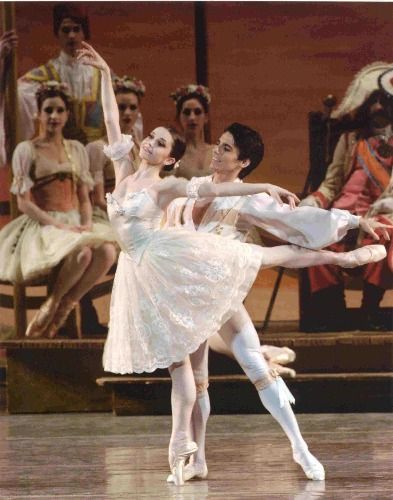

The evening before Valentine’s Day, Megan Fairchild, whose charming looks and diminutive stature echo her surname, made a notable local debut as Swanilda in the New York City Ballet’s Balanchine-Danilova Coppélia and was promoted to the rank of soloist. Not a bad day for a nineteen-year-old who joined the corps de ballet less than a year and a half ago.

What do we know about Fairchild? She trained primarily in her native Salt Lake City, at the school associated with Ballet West. In her subsequent brief sojourn at the School of American Ballet, the NYCB’s hothouse, she copped the academy’s highest award. Once in the company, she stood out almost immediately for her appeal and her technical prowess; she’s extraordinarily swift, strong, clear, and daring. Moreover, she’s now desperately needed as a partner for Joaquin De Luz, the tiny fireball recently imported from American Ballet Theatre, who played Franz to her Swanilda and will be paired with her in the Bluebird pas de deux in the upcoming two-week run of The Sleeping Beauty.

Fairchild has the face of a pretty child, all ingenuous sweetness and joy. What’s more, with its huge, widely spaced eyes, it’s an eloquent stage face. True, her knees seem slightly knobbly, and her feet (as well as hands) are disproportionately long for a person her size, yet every seasoned balletomane knows that the better the dancer, the less deviations from the prevailing classical ideal seem to matter. Being built on such a petite scale may exclude Fairchild from ballerina roles requiring physical grandeur, but her future is assured as a virtuoso and a soubrette. More important than anatomy, at the moment, is Fairchild’s mettle—not just her technical virtuosity, which is formidable, but her appetite for dancing. She seems confident, fearless, elated at having come into what is clearly her rightful kingdom, and of course she dances much larger than her size.

It remains to be seen what, if anything, lies below this surface. In the two casts of Coppélia that I saw, the main roles—Swanilda, Franz, and Dr. Coppélius—have been reduced to near-caricature. Watching them, I thought, like Alice, “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!” The dancers who originated these roles—Patricia McBride, Helgi Tomasson, and Shaun O’Brien—gave them a deep human dimension that in no way diminished the ballet’s bright comedy but, rather, enhanced it. The present production lacks that depth, just as it lacks wit and, most significant, the contrast between two neighboring worlds: that of the village square on which the sun shines perpetually, guaranteeing happy endings, and that of Dr. Coppélius’s workshop—dark, obsessive, and grotesque. Fairchild can’t be expected to enlarge her portrayal of Swanilda until she’s made aware of the subtle matrix in which the character operates. She has already earned her promotion; in terms of sheer dancing, her work is exhilarating. Now she needs the kind of staging and coaching that will encourage her to develop into an artist.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Megan Fairchild and Joaquin De Luz in George Balanchine’s Coppélia

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

BALANCHINE AT HOME #6: RESETTING GEMS

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

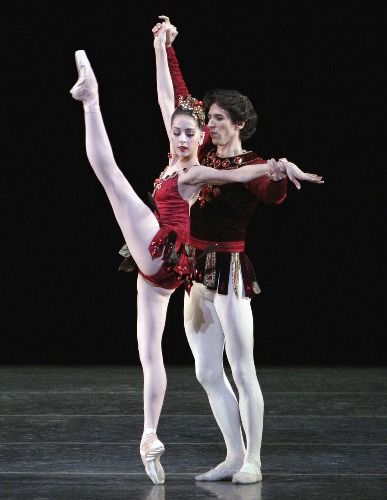

At the time of its creation for the New York City ballet in 1967,  Balanchine’s Jewels was much touted as the first program-length plotless ballet ever. The claim—good marketing fodder, like the anecdotes about the choreographer’s “fondling” a cache of gems, courtesy Van Cleef and Arpels—is tenuous. It is actually three discrete ballets—Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds—each independent of its sisters, as we saw subsequently, when Rubies successfully entered the repertory of other companies as a stand-alone.

Balanchine’s Jewels was much touted as the first program-length plotless ballet ever. The claim—good marketing fodder, like the anecdotes about the choreographer’s “fondling” a cache of gems, courtesy Van Cleef and Arpels—is tenuous. It is actually three discrete ballets—Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds—each independent of its sisters, as we saw subsequently, when Rubies successfully entered the repertory of other companies as a stand-alone.

The distinct difference among the segments of Jewels is the music, which calls on various aspects of Balanchine’s style—the French Fauré for the evocative, Romantic Emeralds; the American Stravinsky (like Balanchine, a Russian transplanted to New York) for the brash, jazzy Rubies; the nineteenth-century Russian Tchaikovsky for Diamonds. The latter two composers, of course, were Balanchine’s closest collaborators.

The segments vary in strength. Diamonds has always seemed to me to be the weakest—a reiteration of familiar Petipa-derived devices, apart from its poignant pas de deux—but that’s partly because it doesn’t hold a candle to another Balanchine evocation of the grandeur of imperial Russia (and the imperial Russian ballet), Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 (né Ballet Imperial). Rubies epitomizes the New World breakneck energy and syncopated rhythm that seized Balanchine’s imagination when he emigrated to urban America and fueled it for the rest of his career. The haunting Emeralds, conjuring up love not as it is, but as it’s remembered, has always been my favorite. In atmospheric force, its price is above rubies.

Originally, the unifying element of Jewels, apart from Balanchine’s sensibility, was the set—overhead, the same simple jewel-bedecked sky, below a cleared space for the action, the lighting shifting from green to red to white, according to the gem being celebrated. Peter Harvey, who created that décor, has come up with a new one for the Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration. Program notes claim that it’s meant to make the ballet look more contemporary (as if it needed cosmetic surgery!). What it does is intrude upon the choreography’s air space and, egregiously, like those extended labels for art works in museums, “interpret” the nature of the individual ballets (as if such choreography needed explaining!).

Emeralds, once “a green thought in a green shade,” has acquired a backdrop suggesting a woodland park, with strings of vulgarly enlarged brilliants looped overhead, as if for a low-end fête champêtre. Rubies, a seize-your-eyes ballet, must now fight for attention with a vicious abstraction of narrow vermilion columns that pierce the space vertically like exclamation points and crisscross in the heavens to fence in a fiery thundercloud; red glitter-glue is applied here and there for entirely superfluous emphasis. Diamonds has been converted to Snow, with backdrop and side pieces a wallpaper of white swirls against a meteorologically incorrect blue sky. An etching of black lines, like a beginner’s efforts with ruler and compass, provide a visual equivalent of static, while the requisite sparkling gems assemble themselves as overgrown snowflakes. The effect is everywhere ugly and claustrophobic.

As for the dancing in the current production of Jewels, there’s no point in my reiterating the complaints I’ve already made in this “Balanchine at Home” series about unfathomable casting, the lack of an empowering vision about the ballets, and the lamentable absence of coaching from the originators of the great Balanchine roles. I’d rather concentrate on some very good and interesting dancing in the two casts I saw.

In Emeralds, Miranda Weese, cast against type in the role Violette Verdy originated, was technically immaculate, cold, and voluptuous. She gave every phrase its carefully considered due and, by her second performance, had loosened up just enough, gained sufficient confidence in what she was doing, to make this carefully thought out rendition heart-catching. Of all the dancers I saw in Jewels this time round, Weese, from whom I’d least expect it, was the only one who made me feel the surge of profound, complex emotion, inexpressible in words, that used to be an all-but-guaranteed experience in watching Balanchine. I also admired Pascal van Kipnis in the pas de trois, where she captured the strange and wonderful combination of devotion to classical form and delight in sheer decoration typical of French culture.

Alexandra Ansanelli and Damian Woetzel can’t compare to Patricia McBride and Edward Villella, the original central pair in Rubies, who made their performance a glorious duel of wits. Still, this new team is altogether up to its assignment in terms of bravura technique and sensitivity to maverick timing. Woetzel needs to recover the street-smart aspect of his dancing persona evident in the brash performances of his early career, while Ansanelli, a very young principal, needs only someone to assure her she doesn’t have to be darling.

The tall, odd-girl-out role was entrusted to a relative newcomer to the company, Teresa Reichlen. She’s a throwback to a Balanchine type—pinhead, incredibly long legs—that the company no longer cultivates with ardor, though some key roles in the rep are based on it. The type, which Balanchine probably extrapolated from the image of the American showgirl—comes in two varieties: sharp and brittle or luscious. Reichlen, with her lush thighs and uncanny pliability, belongs to the latter group. She’s part goddess, part freak of nature, and, perhaps because she’s still inexperienced, seemingly innocent of her own effect. I’ve never seen anyone I’ve liked as much in this role.

In Diamonds, Maria Kowroski, City Ballet’s adagio specialist, with Philip Neal as her cavalier, made the pas de deux elegant and meaningful, a privileged glimpse into the very nature of a tsarina—a young woman subject to the urgings of love and the obligations of aristocratic duty, whose responses are all the more touching for being cloaked in exemplary behavior. Now I’ve gone and made the ballet sound as if it enacts a story. No, it’s both plotless and characterless, free from any of the literal stuff that can be pinned down in a program note. But the genius of Balanchine ensures that every viewer, on every viewing of Diamonds, can derive a new story—as well as new personas and new implications—from the rich store of potent suggestions the choreographer has planted in the ballet, all the while claiming that he was simply responding to the dictates of the music.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Alexandra Ansanelli and Damian Woetzel in George Balanchine’s Rubies

© 2004 Tobi Tobias