A lovely intimate exhibition . . . The entire room seems filled with the fragrance of roses. Village Voice 5/20/04

BALLET GALORE: WEEK #3

American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / May 10 – July 3, 2004

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 29, 2004

AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE: GALA

American Ballet Theatre’s opening night gala was a model of good taste. The company’s well-heeled supporters, definitely part of the show as they milled about the lobby and curving staircases of the Metropolitan Opera House, were exquisitely dressed. Immaculately groomed men in the black and white uniform their role requires provided a complementary background for their gaudier ladies. The women’s ensembles—a preponderance of them cut Botticelli-style from delicate fabrics in springtime hues—constituted a delectable fashion parade (and were duly ogled as such by the more pedestrian crowd peering over the balcony rails). The onstage entertainment was equally graceful, the many entries on evening’s program scrupulously chosen and balanced. Amidst all this refinement, I must admit, I almost missed the raw vulgarity—on both sides of the footlights—of the Bad Old Days: the garish gowns-from-hell, the acrobatic variations on the theme of the 32 fouettés.

If the program was, as my date remarked, “all arias, no recitative,” the smorgasbord (to shift metaphors) approach was appropriate to the occasion—providing a taste of things, no deep immersion—and consciously reflected ABT’s sense of its present identity.

Represented first and foremost was the idea of ABT as a custodian of what can loosely be called “the heritage”—classics from the nineteenth century and latter-day works explicitly declaring their adherence to that tradition. The performance opened with the first movement of George Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial, and it’s significant that ABT’s production of the piece harks back to the old version, which evoked the glories of tsarist Russia in its costumes and décor, though the New York City Ballet has itself moved on to a streamlined scenic investiture and has renamed the ballet after its music, Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2. Representing the actual nineteenth-century part of the heritage category were the extended unison adagio for the female ensemble from the Kingdom of the Shades scene of La Bayadère and chunks of both classical and “Hungarian” passages from the company’s new production of Raymonda, which is about to have its official American premiere.

All three excerpts, and they were substantial ones, were performed with great care, reflecting admirable commitment and hard work from the dancers and their coaches. For the most part, though, the material didn’t quite take wing. The company seems caught between the deliberate Russian style with its sculptural and soulful beauties, and American style, with its speed, sharpness, and verve. Despite its good intentions—and, indeed, its frequent beauties—the dancing seemed deficient in breath, musicality, and, above all, spontaneity. Only the Bolshoi-bred Nina Ananiashvili, in Raymonda, looked fully at ease with her assignment, confidently opting for Russian sublimity as if the alternatives were irrelevant to her identity as a ballerina.

Two pièces d’occasion proved engaging enough to be repeated on other occasions. Carmen Fantasy featured the onstage performance of the violin virtuosa Sarah Chang, gowned in red sequins, playing Pablo de Sarasate’s score with fiendish precision and wild feeling. Kirk Peterson’s choreography is a distillation of the Carmen theme—an elixir of tawdry glamour, bad blood between the lovers, voyeurs and provocateurs in the form of cigarette girls, and so on. Miraculously Peterson keeps his material from lapsing into Backstreet Spanish clichés; instead, he makes the dancing swift, vivacious, technically and atmospherically out for blood—and astonishingly contemporary.

To honor that seemingly ageless man of the ballet theater, the soon to turn 90 Frederic Franklin—still a force in coaching and in retrieving worthy old ballets from limbo, as well as a sometime performer—ABT’s artistic director Kevin McKenzie devised the punning A Sweet for Freddie. The affectionate bagatelle invokes Franklin’s long identification with Coppélia, which ABT will present later in the season. (Once upon a time, Franklin played Franz to Alexandra Danilova’s memorable Swanilda for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo; in later years he moved on to a finely etched portrayal of Dr. Coppélius and to stage the ballet as well.)

McKenzie generously gives the debonair Franklin two Swanildas to waltz with (Amanda McKerrow and Ashley Tuttle, the most gentle-tempered of ABT’s ballerinas), and then provides two more, each eventually furnished with a slightly dumb, slightly loutish Franz. From time to time the multiple Swanildas lapse into Coppélia’s mechanical-doll state and have to be rescued from such restrictions on their mobility and élan through a bit of Freddie’s trenchant yet graceful mime. At the end, Franklin gets to leave with all four beauties on his arm, their swains registering bafflement as to how the dude brought it off.

The indelible moment of the piece comes right up top, where Franklin, dapper in evening dress, enters and strolls briskly down the diagonal of the Met’s enormous stage with the fluency of a well-exercised fellow one quarter his age. He doesn’t look like he’s dancing, and he’s immune to the affectations of performing. He simply looks like he’s walking—on a clear day in mild weather, certain as any instinctively sanguine man can be that the future is about to offer him unexpected delights.

In the program’s gimmick department—an element absolutely essential to galas—we got David Parson’s Caught, which uses strobe lighting to freeze-frame its solo performer (here Angel Corella) in a swift succession of suspended-in-air positions, and Christian’s Spuck’s Le Grand Pas de Deux, a spoof of the genre dependent on junior high school humor, emphatically performed by Irina Dvorovenko and Maxim Beloserkovsky.

True to its mission, the evening showcased the company’s extraordinary constellation of stars—among them, in addition to those noted above, Alessandra Ferri and Julio Bocca, gorgeously lascivious in the bedroom pas de deux from Kenneth Macmillan’s Manon; Gillian Murphy and Ethan Stiefel, mistaking the tone of Balanchine’s Tarantella, but dazzling nevertheless; and Jose Manuel Carreño as both take-your-breath-away technician and the guy everyone wants to go home with, in his solo from the bravura Diana and Acteon pas de deux. It also managed, with the Kingdom of the Shades passage, to pay due homage to its ensemble, from which the next generation of stars will spring.

NEW YORK CITY BALLET: CHRISTOPHER WHEELDON’S SHAMBARDS

“Is this a word we’re supposed to know?” a fellow was asking in the intermission that followed Shambards, Christopher Wheeldon’s latest work for the New York City Ballet. Well, no, and the audience would have benefited from the elucidation that was available in the press kit but not in the house program. The ballet’s score was commissioned from the Scottish composer James MacMillan, who titled its middle section “Shambards” after an epithet in an Edwin Muir poem that mourns the destruction of the national ethos, calling Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott “sham bards of a sham nation.”

Wheeldon’s ballet, which is semi-abstract, seems only vaguely related to this issue. It prioritizes patterning, with an ensemble that moves in intricate sharply-etched configurations. The corps work is infused with references to tightly controlled shape—in the parades of Scottish bagpipers, Highland dancing, and the intricate formalities of Celtic design. All this essentially decorative business is carried out cleverly and meticulously in the ballet’s three movements. The result, though, feels too neat, too clean, too self-conscious. Its lack of organic impulse leaves it devoid of sweep and surprise.

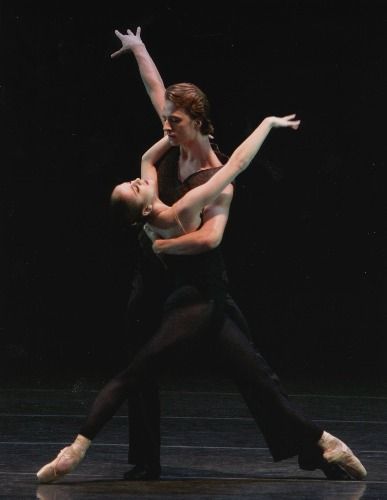

Punctiliously positioned against the corps work are some baffling exercises for the soloists. In the opening section, called “The Beginning,” Carla Körbes and Ask la Cour seem to be merely central figures in the handsome shifting patterns that inexorably take possession of the stage. I read this couple as primogenitors of the race, who emerge from the tribe and are, perhaps, ritually sacrificed at its hands.

“The Middle” focuses on a couple (Miranda Weese and Jock Soto) with more contemporary romantic tsuris. We see disagreement, along with hints that it’s rooted in chronic, low-lying anger. We see sorrow, and then rapprochement; shards of a waltz tune surface in the music. Suddenly the man flings his partner to the floor, drags her around by one arm, then holds her limp body in front of him, as if bearing a corpse. Observers more concerned with the evolution of academic ballet technique than the plight of battered women will explain that Wheeldon is experimenting productively here with the traditional adagio form, “advancing” it so that the lady is free to relinquish her right to verticality for a horizontal position on the ground, her gentleman friend lending a hand as he looms above her.

“The End” adds two diminutive pairs of virtuosi (Ashley Bouder and Daniel Ulbricht; Megan Fairchild and Joaquin de Luz) to the ensemble for some immaculately structured dancing in kaleidoscopic patterns. This material escalates from folkish exuberance to the edge of danger, at which point Weese and Soto return to re-enact their catastrophic encounter. Now, instead of presenting her body straight on to the spectators with the air of a horrified penitent, he drags it sullenly into the wings. The ensemble, which had arranged itself like an allée of trees to frame the terrible scene, simply melts away in the descending darkness, as if it had been destroyed by what it witnessed. If you work hard, you can make the onstage scenario fit the Muir.

Holly Hynes has created stunningly simple costumes for Shambards in a palette of browns, grays, russet, claret, and ebony. A set of skirts that look like kilts with some bounce to them is nothing less than ingenious. Mark Stanley has worked complementary wonders with the lighting, rendering the stage dense with brooding and threat.

The very best thing about Shambards is that it provides a featured role for Körbes, a nascent ballerina worthy of far more significant assignments than she’s currently getting. Indeed, she’s the only one of the company’s young women on the rise who would be perfect in both female roles in the NYCB’s most rewarding excursion to the Highlands, Balanchine’s Scotch Symphony.

HERE ON A VISIT:

I. NYCB: LORNA FEIJÓO & GONZALO GARCIA

Guest dancers from companies with a “Balanchine connection”—through their artistic directors, past or present, and their repertory—are adding spice to the NYCB’s already eventful season. To date, the most gratifying visitors have been Lorna Feijóo (currently with Boston Ballet) and Gonzalo Garcia (from San Francisco Ballet). Although neither of them seems destined by training to be an exemplar of the Balanchine style, they revivified the exhilarating Ballo della Regina.

Feijóo, a product of Havana’s National Ballet School and a former principal with Ballet Nacional de Cuba, displays the virtues of that tradition—killer technique coupled with fervent feeling. Think Alicia Alonso. To my mind (I saw her work with the Cuban company), Feijóo is essentially a Romantic dancer, and she didn’t, indeed, embody the qualities of fresh-air fleetness and crispness on which the Ballo role, originated by Merrill Ashley, was built. Yet her performance—full of exuberance grace, eager to please yet not show-offy—was both delightful and persuasive.

Gonzalo Garcia, who is only 24, trained in his birthplace, Spain, before emigrating to San Francisco. Along the way, he seems to have won prizes at every ballet-competition in sight: youngest to take the gold at the Prix de Lausanne, and so on. In Ballo, he looked like a boy dancing not for the gold but for the hell of it, out of sheer animal spirits. Arms loose and free, he seemed to gambol, now over the earth, like Pan, and just as easily, like Ariel, in the air. He brought off the virtuoso feats the choreography requires without emphasizing them, incorporating them instead into the coursing flow of the movement.

Beyond their command of the formidable technique Ballo demands, both dancers displayed an ardent involvement with the feelings that lie latent in the choreography as well as an intense communication with each other. (Risky as it is to generalize, passion, too often absent from classical dancers who are American- born and –bred, seems to be the birthright of those whose mother tongue is Spanish. It must be something in the culture.) Wrongful though kidnapping may be, I’ll bet New York balletomanes have been speculating on the possibility of Feijóo’s and, especially, Garcia’s remaining with the hosts of their recent brief encounter.

II. ABT: ROBERTA MARQUEZ

Remarkable dancers from Elsewhere have long been a staple of the star-conscious American Ballet Theatre. The Kirov’s Natalia Makarova was just one such acquisition, and it was in her staging of La Bayadère that the Brazilian-born and –trained Roberta Marquez has been introduced to stateside fans, first in DC, now in New York.

The 26-year-old Marquez is a principal with the Municipal Theatre Ballet in Rio de Janiero and a guest artist with England’s Royal Ballet. She’s is an extremely petite woman, small and delicate enough to make her partner, the concisely built Ethan Stiefel, look bulking and towering—way macho. If she is not a great artist, she is clearly a star. The earmarks? Impressive technique with the daring to match, sensational projection, and, I suspect, the kind of confidence and desire usually reserved for people performing acts that are going to result in military medals or canonization.

She may be small, but she dances huge. In Bayadère, from the moment her veil is lifted to reveal her piquant face and a body that is tremulous even in stillness, she’s eager to reveal Nikiya’s single-minded passion for a lover whose heroism is nowhere up to hers, the hurt-child pathos proper to the situation, and (half-hidden, of course) the character’s yen for immolation. (Nikiya’s finest hour, Bayadère watchers know, comes after her death).

As the living and loving, rivaled and wronged Nikiya, Marquez is persuasive in her earnestness, admirable in her commitment to the melodrama of the story. Once Nikiya is a ghost, Marquez duly makes her as remote and disembodied as a spirit should be, all the while attempting to convey the tenderness and longing Nikiya still feels for her sorry lover. Somewhere along the way, though, Marquez loses her grip on her viewers’ rapt fascination and belief—because her conspicuous physical prowess and her apt characterization lack the support of that indefinable yet immediately recognizable element we call “soul.”

In many ways the model for Marquez is, in her own generation, Alina Cojocaru, and, before that, Gelsey Kirkland. Marquez is similar to them physically, arguably their near-equal technically, but she lacks their incandescent spirit. Perhaps it is lying dormant in her and will surface with time. I hope so, but I’m not counting on it, since the quality is one that, in ordinary life as well as artistic life, is usually evident by adolescence. Such a blessing is impossible to conceal.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Carla Körbes and Ask la Cour, in Christopher Wheeldon’s Shambards

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

New York Theatre Ballet

Frederick Ashton’s 1930 “Capriol Suite,” a gloss on 16th-century dance forms, mingles peasants and aristocrats, lusty ebullience and aloof grace, easy charm and stabs of poignant imagination. Village Voice 5/14/04

John Ollom

They say everyone has one novel in him. It’s the fruit of a life’s experience–the tale, the feelings. John Ollom certainly does, but he happens to be a choreographer. Village Voice 5/14/04

Company Rindfleisch

Slow, subdued, and handsome, Elke Rindfleisch’s “Enamoured” traces the vagaries of relationships–amorous and the inevitable opposite. Village Voice 5/14/04

BALLET GALORE: WEEK #2

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 29, 2004

Following are comments on the highlights of the second week in the New York City Ballet’s spring season, Part II of the company’s Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration.

LIEBESLIEDER WALZER

Balanchine’s Liebeslieder Walzer, created in 1960 and given three luminous performances in the New York City Ballet’s Balanchine 100 centennial celebration, lasts for about an hour. It is so lovely and so infinitely inventive, you feel you could watch it forever.

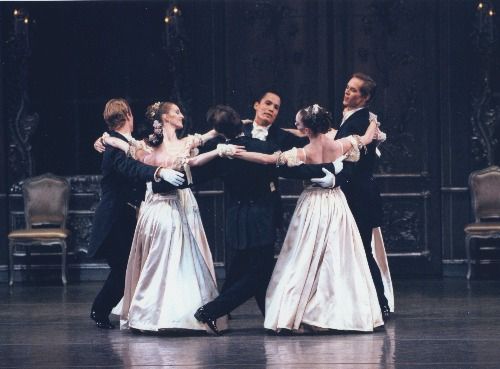

A quartet of singers and a pair of pianists perform onstage for four couples who dance, the conceit being that they are all participating in a musical evening at home, a familiar pastime among the upper classes of nineteenth-century Europe. Their music consists of two Brahms song cycles whose titles translate as Love Song Waltzes and New Love Song Waltzes. Their setting, designed by David Mitchell and said to be inspired by Munich’s Amalienburg Palace, is an elegant interior with filigreed paneling and furnishings to suit, the space gleaming bronze and pearly gray, as if softly lit by the candles in the wall sconces and the crowning chandelier. Dancers and singers wear similar period evening dress. Karinska’s now legendary gowns for the women—cut with panache from luxurious low-gloss fabric, each in a different, barely perceptible, pale shade of off-white—are beautiful in stasis and ravishing in motion.

The choreography for the first half of Liebeslieder is an extension, along balletic lines, of social dancing, specifically the waltz, but it is no more like decorous social dancing than are the duets of Fred and Ginger. It constitutes a lexicon of movement, timing, impulse, and suggested emotion—all kept within the confines of waltz tempo and the situation that has been proposed. There are lifts, for example, but they skim the ground, never vault into the air; if on occasion they soar a little higher, the woman’s partner still holds her vertical, as if she had just floated some inches upward from her erect dancing position. All the while, the tours de force of timing are coupled with mercurial shifts in mood. The tact, intelligence, and sheer theatrical genius with which everything is deployed seems nothing short of miraculous.

It’s important to note, I think, that Liebeslieder’s four couples form a community of familiar friends. They gather regularly, one is lead to assume, in each other’s exquisitely appointed homes for an evening of music and dancing. They’re more than acquaintances surely, and perhaps, on occasion or merely through the mind’s fugitive caprices, cross-couple intimates (though ultimately faithful to their partners). From time to time, two, three, or all four couples dance together, and this periodic deflection from the duet form that dominates the dance is perfectly calibrated, and frequently astonishing. Besides providing variety, the larger interaction roots the proceedings in the idea of social intercourse, proposing it not merely an amenity but as an element crucial to a life fully lived and fully felt.

When the first songbook comes to a close, the dancers throw open the room’s three double doors and escape into the moonlit gardens that one imagines lie beyond—for a breath of fresh air, or perhaps to exchange sentiments that belong to two people alone. Some moments later, the artificial candles extinguished, the lighting given a blue cast that heightens the impression of night and mystery, the dancers reappear. The women who trod the floor lightly enough in their heeled ballroom slippers and voluminous ground-brushing skirts are now clad in pointe shoes and gauzy tutus with blossom- and dewdrop-studded ribbons lying just visible under the top layers of mist-tinted tulle. The flesh-and-blood inhabitants of the gracious room have been transformed into the creatures of their own dreams, launched into a space of uncertain boundaries.

In this part of the ballet, each couple has more time alone, unwatched by the others, because the illusion of a social occasion has been shed, and because the dancing has shifted to a fantasy world, a venue that—apart, of course, from folies à deux—is essentially private. The choreography for the latter half of Liebeslieder is, as you’d expect, more conventionally balletic than it was in the first—swifter, more daring, more intense—but it retains vestiges of social dance that link it to all that has gone before, and, as before, it is suffused with heady emotion. Eventually, pair by pair, the dancers flee even this less circumscribed space, and the stage is abandoned to the musicians.

The lyrics of the final song come from Goethe: “Now, you Muses, enough! In vain you strive to describe how misery and happiness alternate in a loving breast. You cannot heal the wounds that Amor has caused, but solace can come only from you, Kindly Ones.” Slowly, again in couples, the dancers return, once more in mufti, to sit or stand meditatively, listening. When the music concludes, they gently applaud the musicians with their immaculately gloved hands as the curtain falls.

Liebeslieder has no narrative content, unless you count the precipitous shift from reality to ecstasy that occurs between its two parts as a specific event in time. (I don’t; I think it’s the kind of leap lyric poetry makes, independent of plot.) Neither is the choreography tethered to the lyrics of the songs. Its subject, apart from the music itself (as the choreographer might have argued), is, I would say, the many faces of love. If there is any aspect of civilized love that Balanchine hasn’t treated here, I can’t imagine what it might be. Charged with moods that fluctuate like spring weather, sometimes within a single brief duet, the ballet reveals romance to be, by turns, tender, joyous, pensive, flirtatious, wistful, tempestuous, angry and conciliatory almost in a single breath, occasionally near-tragic. Love in Liebeslieder is imbued with nostalgia, existing as much in perfumed memory as in the ardent—often impetuous—declarations of a present moment. It is shadowed here and there by intimations of death, as if affairs of the heart could have no meaning without reference to the inevitable event that would annihilate them. If you’re susceptible, the ballet stirs all your hidden feelings about love, perhaps even a few you’ve been keeping secret from yourself.

Innumerable leitmotifs weave through the ballet, surfacing and ebbing, according to the “climate” of a particular performance and the individual viewer’s focus of attention. Over the years, observers have detected a theme they refer to as “the girl who is going to die.” Her initial duet with her partner is happy and bounding, almost like a polka. But in their second she seems to be attempting to tell her lover some terrible secret, one that he already knows in his heart but can’t bear to hear. He shields his face with the back of his white-gloved hand; her lips, ready, finally, to whisper the fateful words, nearly brush his palm. And all the while they go on dancing; none of the lightly etched gestures and poses of this little drama interrupt or override the momentum of their movement to the music. In a third duet, though, she swoons backward in his arms, hand to brow, the image of a person overtaken by faintness or fever. Regaining her footing, she moves away from her partner, as if illness likely to prove mortal had already isolated her from the consolation of his embrace. After a moment, they come together once more, but when she falters in his arms a second time, he lifts her extended body horizontally so that, for a brief but indelible moment, she is already a corpse. One of her arms is folded so that her hand rests on her breast; the lavish folds of her long pale skirt streaming away from her body resemble a winding sheet that has not yet been pinned into place. In Part II the relationship of the pair has almost no dramatic implications, but as the role is danced today, the young woman has become cousin to The Sleeping Beauty’s Aurora revealed to Prince Désiré as a vision and Giselle’s doomed heroine returned to Earth as a spirit—in other words, impalpable.

Grace governs this ballet. The dancing, with the waltz as its heartbeat, is graceful. The behavior of the inhabitants of that exquisite room is as graceful in its sense of decorum’s parameters as it is in its gestures. And the dancing figures, first experiencing a gamut of the subtle emotions that belong the real life of people with high sensibility, then suddenly projected into the wilder world of their imagination and yet safely returned home, are surely in a state of grace.

At the premiere of Liebeslieder, in 1960, they took the house lights down to half for the extended pause between the two sections. I remember sitting in the hushed twilight and thinking, This is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen. I’ve had little cause to change my mind since, despite casts subsequent to the original one that were not quite as wonderful. To my mind, the company’s current rendition is the finest—the most coherent as an entity, and the most moving—since the ballet’s first season.

The original dancers were: Diana Adams and Bill Carter; Melissa Hayden and Jonathan Watts; Jillana and Conrad Ludlow; Violette Verdy and Nicholas Magallanes. The current dancers are: Darci Kistler (in the Adams role) and Philip Neal; Kyra Nichols (Verdy) and Jock Soto; Miranda Weese (Jillana) and Jared Angle; Wendy Whelan (Hayden) and Nikolaj Hübbe.

Even today Liebeslieder remains charged with the dancing personae of the artists on whom it was created. Yet it is magically potent for viewers ignorant of past. Just this week, a burgeoning ballet fan told me, “I’ve never seen anything staged with such a combination of fragrance and philosophical depth.”

EPISODES

Because of the way the NYCB has organized the second half of its Balanchine 100 centennial celebration–with “Tribute” evenings that cluster ballets to scores from a particular nation—a surfeit of lushness prevailed in the first two weeks’ programs, when first Germany then Austria took their turn in the spotlight. Entering the rep at the close of week two, Episodes, to a handful of typically brief, stringent pieces by Webern, was a welcome relief—a dry martini, citrus sorbet.

The current production is stunning. It’s performed on a bare stage against a pearly blue-gray cyclorama and side pieces, their cool simplicity emphasizing the high vault of space stretching over the dancers’ heads. In this empyrean emptiness, clad in severe black practice clothes and moving with impeccable clarity, the dancing figures conjure up images of graphs, musical scores, Asian calligraphy. At the same time, they seem very human, acutely attentive to nuance as they execute their austere, enigmatic rites. It’s startling to realize that, forward-looking as Episodes was when it was made in 1959 and forward-looking as it remains, the choreography might be the skeleton of crystalline passages from Petipa.

Symphony, Opus 21:

The steps seem to fall between the notes, both steps and notes spare and dry, compelling in their simultaneous oddity and logic. Here music and choreography appear to be the related languages of a locale in interstellar space.

Relaxed but remote, the performers’ faces are uninflected by expression. Their bodies, deployed in space and time, do all the talking.

When the dancers need to stop what they’re doing and get to another spot on the stage to begin again, they just quit, without flourishes, and walk casually to where they need to be. This tactic is unheard of in classical ballet.

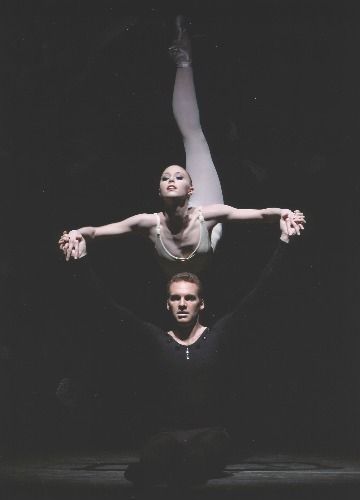

Five Pieces, Opus 10:

A duet for strangers in the night.

The space is so dark it seems borderless. Roving spotlights, beamed from above, pick out the two figures—a man (James Fayette) in black, with only a sprinkling of reflective material at the neckline to increase his visibility, the woman (Teresa Reichlen) sheathed in chalk white. She’s one of the company’s Tall Ones, with legs that go on forever, and uncannily malleable. Awed, curious, and occasionally baffled, the man manipulates her fantastic body, and she cooperates as if being the clay in his hands were her chosen destiny, twisting and twining into seemingly impossible positions. The effect is eerie, sometimes grotesque, occasionally funny. One thinks of Balanchine coming to America—the choreographer led, through the cryptic workings of Fate, to the land of extraordinary female anatomy, and setting to work.

Concerto, Opus 24:

At this point, a ballet with a normal regard for convention would offer its centerpiece—a love pas de deux. This duet is one, of sorts, in a way that’s ironic and illuminating. Pliable as a rubber band, Wendy Whelan exaggerates her loose-jointed, sinuous capabilities, keenly alert to timing and texture. Albert Evans anchors her with his potent theatrical presence. The four women constituting their entourage perform their spider-like maneuvers—all lines and angles, understated, mesmerizing. The weirder the goings-on in this ballet, the more beautiful they are.

Ricercata in six voices from Bach’s “Musical Offering”:

Just when you thought the universe had been reduced to fragments, Webern puts it together again, anatomizing Bach. In the lead, Maria Kowroski and Charles Askegard are angels of coherence. They’re abetted by 14 women who form matrixes that make order visible. Facing the audience straight on, they advance towards it on legs that devour space, or place themselves like markers on an invisible grid, standing erect on their knees. When you notice that this drastic, peculiar image harks back to the opening section of the ballet, you understand that, throughout the piece, Balanchine has been holding the world safely in his hands, rendering it comprehensible despite its elements of chaos, perhaps even relishing those excursions into disorder, like a god at play.

OCCASIONS:

I.

May 1, the New York City Ballet declared its performance—of Balanchine works to the music of German composers—to be Alumni Night. It was the public face of a weekend-long reunion of NYCB dancers, some 200 of them, dating back to the company’s official beginning in 1948. With offhand charm, Peter Martins emceed the onstage presentation of dancers who had originated or inherited principal roles in the ballets about to be danced. The ballets were : Kammermusik No. 2, Liebeslieder Walzer, and Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet. The dancers were: Jacques d’Amboise, Karin von Aroldingen, Gloria Govrin, Melissa Hayden, Jillana, Allegra Kent, Sean Lavery, Sara Leland, Colleen Neary, Adam Lϋders, Mimi Paul, and Suki Schorer.

Then Martins asked the other alums present, seated in the audience, to stand. Of course the rest of us wanted to peer and cheer. And so we did, long and loud. We were looking at nearly six decades’ worth of remarkable people, major and minor talents alike, who had dedicated themselves to one of the great communal artistic enterprises of the twentieth century—the creation and (since a dance lives only in its performance) the ongoing re-creation of Balanchine’s ballets.

It was interesting to identify these notable dancers, featured and ensemble players alike. Folded into the house program was a list of their names, most of which, to veteran fans, evoked images and memories far more vivid than those provided by the entries on the old-acquaintance rosters of our college reunions. It was absorbing as well to contemplate the further unfurling of their careers after they left the stage. Many, of course, have gone on to the logical extensions of a dancing life as artistic directors, choreographers, teachers, stagers, coaches, and members of dance institutions’ production and administrative staffs—often with the NYCB and its affiliate academy, the School of American Ballet. Others have ventured farther afield, into a range of professions that includes writing and photography, medicine and the law. And it was tantalizing, since we knew them in their onstage incarnations primarily as physical presences, to find out how they look now, in body and dress, as “pedestrians.” But no matter how avidly we stared and guessed, curiosity and gossip being fundamental to human nature, I, for one, had to admit that what they offered Balanchine and their audience remains the most unusual and fascinating thing about them. A major part of their being, and the element that united their disparate temperaments, had been, in their performances over all those years, right out there in front of our eyes.

II.

If the New York City Ballet’s Alumni Night paid a personal, suitably low-key homage to Balanchine through the generations of dancers associated with him, a special program on May 5, “Lincoln Center Celebrates Balanchine 100,” was its tell-the-world statement. Before a packed—and exceedingly well dressed—house (the occasion served as the NYCB’s Spring Gala), the 12 resident institutions of Lincoln Center joined forces in an evening of music, dance, film, and talk. It was beamed out, live, onto a Brobdingnagian outdoor T.V. screen on Lincoln Center Plaza (where folding chairs had been set up for spectators undeterred by threats of rain), telecast by PBS into millions of homes with no dress requirements whatsoever, and thus recorded for posterity.

The program was, predictably, star-studded, decorous, and entertaining. If provocative, introspective, or simply thrilling was what you were after, this was not your night. Indeed, it hardly represented Balanchine’s immense achievement, since it relied, for the most part, on segments of ballets guaranteed to please easily, like the gypsy finale of Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet and the grand conclusion of Vienna Waltzes, with its dozens of couples uniformed in sumptuous black and white evening clothes sweeping around magnificently in a mirrored ballroom that doubles their numbers and impact. The most “advanced” work on the program was Concerto Barocco, represented by its sublime adagio, sublimely danced by Maria Kowroski, with James Fayette as her attentive, anonymous cavalier. But the radical choreography with which Balanchine changed the face of classical dancing—in works like Agon, Episodes, Violin Concerto, and Symphony in Three Movements—might never have existed, for all this program revealed about them.

There were some agreeable small and subtle touches, though. Placido Domingo’s rendition of Tchaikovsky’s “None but the Lonely Heart”—purportedly one of Mr. B’s favorite songs—was echoed by the Gershwin song “The Man I Love,” with Alexandra Ansanelli and Nilas Martins dancing the segment Balanchine choreographed to that music in his Who Cares? This entry had Wynton Marsalis playing trumpet onstage, an event that had itself been heralded by the program’s starting with the trumpet duo Fanfare for a New Theater, composed by Stravinsky for the opening, in 1964, of the New York State Theater, built to house Balanchine’s enterprise. And of course there were heavenly, if intermittent, dance moments, such the perfect timing and tone with which Peter Boal and Yvonne Borree concluded a section of Duo Concertant, in which they’re accompanied by an onstage pianist and violinist, turning away from the audience and toward the instrumentalists—just slightly, and with just a suggestion of a bow—as if to indicate that their dancing existed simply to be absorbed back into the music from which it had sprung.

The evening was emceed live by Sarah Jessica Parker, who has no evident Lincoln Center connection, but who rose above her fame to do the job with modesty, freshness, charm, and a wardrobe of three different snazzy evening dresses. On screen, the Broadway choreographer Susan Stroman, associated with the Lincoln Center Theater, told Balanchine stories in a down home style to introduce film and video clips meant, I guess, to reveal the “human” aspect of the choreographer. Balanchine and Stravinsky consuming a pick-up lunch as they worked together. Like that. Situations in which Balanchine was asked to describe what he did and how he did it are patently ludicrous. Does such footage really succeed in domesticating a subject—the achievement of genius—that otherwise leaves us paralyzed with awe?

In truth, though memory-sharing and gala celebrations have their place, there’s no fully adequate way to pay homage to Balanchine. The most useful, and most unendingly difficult, way is to give ongoing vitality to the dances he created by performing them in the style to which, under the choreographer’s own aegis, they were accustomed. The actor Kevin Kline aptly offered these lines, from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, gesturing toward the stage where the dancing happens on the word this: “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.”

Photo credit: Paul Kolnick: (1) George Balanchine’s Liebeslieder Walzer; (2) Teresa Reichlen and James Fayette in Balanchine’s Episodes

Translation of Goethe’s “Nun, ihr Musen, genug”: Emily Ezust

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Tanzmoto

Mohan C. Thomas had the maverick idea of melding Sufi dervish spinning with Latin American dance forms and rhythms. Village Voice 5/10/04

Lyon Opera Ballet

In Philippe Decoufle’s “Tricodex” a wheeled wooden frame creates a proscenium evoking stages of yore; in and around it old-fashioned feats of balance and flying seem to be caught in gaslight illuminating the dark. Village Voice 5/4/04

BALLET GALORE: WEEK #1

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 29, 2004

Following are some comments on the highlights of the opening week in the New York City Ballet’s spring season, Part II of the company’s Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration.

LA VALSE:

I come to Balanchine’s La Valse laden with memories.

Shortly after the ballet’s creation in 1951, I had the privilege of seeing Tanaquil LeClercq in the role of the doomed girl—a striking figure of innocence in the glamorous, corrupt society sweeping feverishly around her. Francisco Moncion was her apt foil, in the role of Death.

Of all the dancers I’ve known who were potent in stillness, Moncion still ranks first; his gravity and projection in this ballet as he gradually but inexorably laid claim to his prey had the effect of smooth, heavy stones dropped into a calm, deep pool.

LeClercq—unique in everything she did, with her intelligence and wit, her long-limbed angular elegance, her chiseled profile, and her inherent mystery—played the ballet’s strange heroine entirely without sentiment. She asked not that you pity her but that you allow your imagination to participate in her fate. If Death took her as his bride because she was young, untouched, lovely, she also went to meet him—with curiosity, even bravado. She accepted the shadowy cloak in which he wrapped her, the macabre accessories with which he adorned her—relishing the jet jewels and plunging her hand into the long inky gloves—not with a reluctance born of fear but first with puzzled equanimity, finally with a rapacious appetite.

In the present production, Rachel Rutherford and Robert Tewsley (as her devoted, baffled suitor, the role created on Nicholas Magallanes), do the originals justice. Both exude the sense of place that makes the ballet potent. And both dance with real dramatic impetus, as if, for them, the story is new and vivid. Rutherford, a lovely but placid dancer, doesn’t possess anything like LeClercq’s instinct for fantasy, but she conjures up a believable and telling persona. She made me think of an adolescent, touching in her folly, who costumes herself in chic depravity and goes out on the town to risk her life.

In the present production, Rachel Rutherford and Robert Tewsley (as her devoted, baffled suitor, the role created on Nicholas Magallanes), do the originals justice. Both exude the sense of place that makes the ballet potent. And both dance with real dramatic impetus, as if, for them, the story is new and vivid. Rutherford, a lovely but placid dancer, doesn’t possess anything like LeClercq’s instinct for fantasy, but she conjures up a believable and telling persona. She made me think of an adolescent, touching in her folly, who costumes herself in chic depravity and goes out on the town to risk her life.

The ensemble dancers perform handsomely enough, but, for the most part, don’t seem to know what the ballet’s about. Blame their inability to probe their material on their own (a failure common among today’s performers) or blame their coaches, as you prefer. But how can they not have heard the frantic, decadent atmosphere in the music? For the entire first half of the ballet, they seem to be enjoying themselves at a pleasant-enough ball.

And Jock Soto, I’m afraid, is all wrong as Death. He has the right physical presence for the role—solemn and striking—but he emotes too much, as self-consciously sinister as a stagy Dracula, and simply does too much, reaching out to seize the girl and rough her up, instead of luring her into his realm through his magnetic presence.

Karinska’s inspired designs for La Valse are, of course, less vulnerable to the changes time inevitably wreaks on the interpretation of choreography. One of the glories of this ballet is the ankle-brushing tutus for the soloist and ensemble women. Overskirts of pearl gray gauze veil layer upon layer of gorgeous yet somehow horrifying color—scarlet, vermilion, magenta, lavender, rose, and tangerine—each gown adhering to one of three different palettes. The hues flame and blend variously when the women whirl on pointe or unfurl their exquisite, powerful legs, as if night and death could never fully conceal the magnificent and terrible sunset preceding the end of the world.

SONATINE:

At the moment of its creation, Sonatine was disguised as a curtain-raiser, a bagatelle, a pièce d’occasion. The occasion was the New York City Ballet’s Ravel Festival of 1975. The year marked the centennial of the composer’s birth and, while Ravel hardly inspired Balanchine’s choreography as Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky did, festivals excited ticket buyers’ interest, and attention to the composer functioned as a tribute to France. (Three decades ago America was not fussing about the local name for pommes frites, but still looking to France as a model of sophistication in the realms of the intellect, the arts, and, of course, cuisine and high fashion.)

The ballet—a duet accompanied by an onstage pianist—proved to be worth keeping, though casting it once the original dancers had left the company has been a challenge. Balanchine made Sonatine for Violette Verdy, a French import, and the ballet was tightly connected to that distinctive dancer’s extraordinary musicality and her piercing intelligence. (Verdy was fittingly partnered by another French dancer, Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux.)

The choreography depicts a partnership that is the acme of civilization. It displays its dancers in a multitude of promenades and gracious bows—to each other, to an unspecified occasion. The delicacy of ornament so prominent in French art surfaces in its small, precise articulations and flourishes. Delving deeper, the piece explores the myriad ways in which two bodies can relate to each other, hands joined, and, equally, how they can relate in space when they separate. The dancers seem to enjoy a state of mutual delight—yet one that is social, not intimate or passionate. Part of their pleasure appears to lie in sharing a standard of exquisite comportment.

Oddly enough, though, the moment in Sonatine that remains unforgettable to me from its early showings is all fervid Romanticism, a vein that keeps surfacing in Balanchine’s work, one that we overlook as we concentrate on the miracles he accomplished in his neoclassical mode. The headier leitmotif proposes a man who is all ardent reverence—call him the Poet; call him Balanchine, if you dare—yearning for an unattainable woman. She is not merely the object of his desire (tangible) but also his inspiration (ineffable). Think of the exalted adoration the man expresses toward the woman who twice vanishes and returns in the final passage of Duo Concertant. Think of the numerous occasions on which Balanchine portrayed Suzanne Farrell as the muse who is the elusive object of the Poet’s worship. Now this is not the way Balanchine usually cast Verdy, whose Cartesian temperament, with its emphasis on clarity and objectivity, was neither a likely purveyor of sheer sensual allure nor a likely object of ecstatic imaginings. But in this little moment I recall from Sonatine, Verdy, for just a few seconds, became such a figure.

At intervals in the dance, the woman leaves her partner, and he, in turn, leaves her. The departures don’t seem to carry any emotional freight; they’re intrinsic to the structure of the piece, allowing for solo work to offset the duet material and offering the temporarily inactive performer a little breather. But when she goes off—I think it’s a third time—the man dances briefly alone, then suddenly crouches low, Werther-like (originally, in the concave shelter of the onstage grand piano, though the position has now been moved to center stage). His despairing attitude leads us to believe she’s gone forever. Then—lo and behold!—she returns. Cued by a shift in the music, he looks up, gazes toward the faraway corner diagonally opposite him, and there she is, just standing there, like a statue gleaming in early morning sunlight. No need for her arm to beckon or for her face to register emotion. Even in dance, there are moments when movement is superfluous. Her mere presence is his entire consolation—his reward, perhaps undeserved, surely unexpected, a stroke of Fate in one of her rare benevolent moods.

This season the company invited a pair of Paris Opera étoiles, Aurélie Dupont and Manuel Legris, to fill the Verdy and Bonnefoux roles, and they made an exquisite job of it. Their execution of the choreography was a tribute to their schooling: very pure, very powerful, very controlled—yet fleetingly inflected with all sorts of subtle shadings. More than the originators of their roles, they allowed their contact to grow increasingly rhapsodic. So much so that the ballet’s ending—they exit whirling on crisscrossing paths to opposite sides of the stage—frustrated expectation. Verdy’s demeanor, on the other hand, hinted from start to finish that Apart was inevitably lovers’ destination.

KYRA NICHOLS:

The New York City Ballet called its all-Balanchine opening night program “French Tribute,” the scores for Walpurgisnacht Ballet, Sonatine, La Valse, and Symphony in C being by Gounod, Ravel, Ravel again, and Bizet, respectively. I’ve always thought that the atmospheric Emeralds section (Fauré) of Jewels was the most deeply French of Balanchine’s ballets, but never mind, the program offered a great deal of loveliness, which, for me, reached its pinnacle with Kyra Nichols’s dancing in Walpurgisnacht.

For the last several years, Nichols has quietly and steadily demonstrated how a ballerina can comport herself with continuing grace and growing luminosity as she nears the close of her performing career. Though time inevitably eroded her phenomenal technical capability, she has never relinquished the key elements—call them principles—of her dancing: the purity, the musicality, the self-presentation so modest, so tactful, so reticent that her dancing figure, offering almost no ego, looks simply like a flowering of the music or perhaps the incarnation of Balanchine’s imagination.

Many of Nichols’s former great roles are now beyond her, but in Walpurgisnacht she was perfect, spinning her silken web, phrase after phrase exquisitely modulated, the material inflected here and there, just fleetingly, with a hint of emotion, but not one you could ever put a name to. Nothing seemed calculated or forced; she moved, despite the intricate artifice classical dancing involves, with the radiance and joy of an ingenuous child. At the ballet’s last moment, when her partner displayed her in profile, perched high on his shoulder, her unbound hair streaming down her back, she looked like a figure on a ship’s prow, guiding her vessel out into uncharted territory, confident that she would encounter fair weather.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: (1) Rachel Rutherford and Robert Tewsley in George Balanchine’s La Valse; (2) Kyra Nichols in Balanchine’s Walpurgisnacht Ballet

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Sharing the Honors

Balanchine, Graham, Ailey, and De Mille appear, separated by perforation lines of course, on the United States Postal Service’s new 37-cent commemorative–American Choreographers. Issue date: May 4, 2004. Village Voice 4/28/04