Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

The Royal Ballet concluded the Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration—an event that demands an encore—by offering irresistible entertainment: three performances of the choreographer’s 1948 Cinderella, set to Prokofiev’s evocative score. The first of them, featuring Alina Cojocaru in the title role, was one of the most intense (and innocent) experiences I’ve had in a lifetime of ballet-going. This ballet is like a perfect children’s book: simple in its means; fluid in imagination; rich in delights that appeal to the eye and echo in the heart; charged with incontrovertible morality.

Yes, morality. Consider this: Cinderella’s saga, so gratifying at the personal level—virtue, much put upon, finally reaping its just rewards of ravishing costume, sleek vehicle, and loving prince—has a larger dimension. It illustrates the triumph of order over chaos. The ballet opens with a scene of domestic discord—the physical and emotional cacophony engendered by the chronic ill will of the Ugly Sisters. The stepsisters’ physical homeliness, which verges on the grotesque, reflects the impulses—envy, vanity, and greed, among other of the Seven Deadlies—that dominate their lives and spoil the daily existence of everyone under their roof, from family down to servants and tradespeople. While the Ugly Sisters create clamor, Cinderella and her father represent harmony and peace. The ballet ends—not with a grand thousand-watt pas de deux, but on a gentle preview of the perfect accord that will prevail in the household of Cinderella and her prince.

And consider this: Cinderella is not merely a nice, goodhearted girl—the sort of person parents used to wish their daughters to become or their sons to marry. No, she is the very emblem of love. She’s charitable—literally to the Beggar Woman, spiritually to the stepsisters, whose hostility she meets with sweet-tempered tolerance and, in matters small and large, forgiveness. Even when she comes into her kingdom, she doesn’t banish those who had earlier relegated her to rags and ashes. (Ashton quietly records at least one of her tormenters’ recognizing this generosity and the luminous soul that extends it—and being just a little transformed).

From the first, Ashton’s Cinderella is seen to be greatly deserving. The Fairy Godmother, in working her magic to bring this unassuming heroine to her rightful destiny, puts the forces of nature at her service. Presenting her retinue to the girl, she seems to say, Here are the seasons. All of the earthly landscape is yours—gardens, forests. And here are the heavens—sun, moon, stars. Here are the hours. Time itself will bow to you, if you obey just one rule. (And Cinderella comes close to breaking that rule only because perfect love—something she knew only once before, from her long-dead mother—has, understandably, distracted her to the point of forgetfulness.)

The idea of terrestrial and celestial forces being summoned to transform Cinderella’s condition is much abetted by Toer van Schayk’s new scenery for the ballet. The appropriately inhospitable parlor of the home in which Cinderella is confined slips away upon the arrival of the Fairy Godmother, to be replaced with a backdrop suggesting the Milky Way. The stage is then transformed into an 18th-century garden for the presentation of Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter, each in her seasonally appropriate grotto, each with a girl-and-boy pair of child attendants who are as motionless and charming as porcelain pastoral figurines. When the Fairy Godmother, echoed by the dozen spirits representing the hours, instructs Cinderella on her curfew, a glowing golden clock, hands pointing to a fateful midnight, is suspended in the night sky, changing its guise on and off to that of a full moon. Once Cinderella is gowned and coached, a star-sprinkled forest gapes wide to reveal an imposing castle in the distance and heavens given over to meteorological fantasy. The ballroom is dishearteningly heavy, but it opens onto a formal garden offering the consolations of fresh air and exquisite proportion. Once, back in the gloom of her childhood home, Cinderella has demonstrated that the shoe fits, an apotheosis shifts the scene again to the bosom of nature, where the hours—now benign rather than warning—have acquired magic wands like the Fairy Godmother’s: star-tipped. The ballet’s final tableau echoes the idea of celestial collaboration; just as the curtain starts to fall, the heavens bless Cinderella and her destined love with a shower of golden stars.

The moral dimension of Cinderella’s character carries straight through to the ballet’s conclusion. Accommodating to the fact that Prokofiev’s score failed to provide for the sort of triumphant pas de deux with which program-length storybook ballets customarily conclude, Ashton excuses his modest heroine from lording her triumph over her foes, even from exulting in it among friendly inferiors. Instead, he assigns her a small duet with her prince in which she simply grows more gentle, more dulcet, and more luminous.

As I’ve said, the performance of this wonderful ballet that was led by Alina Cojocaru had an unforgettable radiance. Her small, delicate build helps her look suitably waif-like as the mistreated Cinderella, but this readymade pathos is quickly counteracted by the sweetness and spunk she gives to the character and by the gorgeous amplitude of her dancing. With experience she will learn to blend the two moods, the pathos and the sanguine resilience, as Margot Fonteyn did so memorably. Meanwhile, one appreciates the fact that Cojocaru’s spirited quality is not a matter of acting; it’s embedded in the speed, precision, and ebullience of her dancing.

In this very young ballerina, sheer beauty of physical proportion and technical perfection are matched. Examples of the latter: the ability to transform a striking still posture into dancing without smudging the imprint of the original shape; the ability to make a stream of minute, evenly measured turning steps precise and liquid at the same time. That sort of thing. Add to these gifts innate grace and musicality and you have something seen perhaps just once in a generation—something, by the way, evident not merely to the aficionados in the audience but to every last person in the house.

I still haven’t mentioned the modesty and sincerity of Cojocaru’s self-presentation (so apt for the role of Cinderella, so welcome on other occasions) or her evident joy in what she’s doing. My praise might be more credible if I could temper it with some minor complaint, but, truth to tell, there isn’t anything about Cojocaru’s dancing that I don’t like.

Johan Kobborg, Cojocaru’s frequent partner, makes a fine prince for her Cinderella. His demeanor may be more friendly than aristocratic, but he’s so unaffectedly agreeable, so infallibly caring, you feel the heroine’s future happiness with him is guaranteed. Like many another Danish-bred dancer, Kobborg maintains an attentive, responsive relationship to his fellow performers that seems entirely genuine. He’s wonderful, for instance, when Cinderella disappears for a moment and he asks the various couples at the ball where she might be, revealing how bereft he feels when nobody knows. Even before midnight strikes and he’s left with nothing of her but a single small, glittering shoe, you see that she has not simply aroused his devotion, but become his entire world. Still, Kobborg is not a danseur noble in looks or manner. Neither is he a topflight virtuoso. So I wonder sometimes—all the while grateful to him for both his engaging dancing and his sympathetic partnering—if he may not be playing Michael Somes to Cojocaru’s Margot Fonteyn. If so, I hope Cojocaru’s Rudolf Nureyev shows up well before she’s past her prime.

The roles of the Ugly Sisters originated by the darkly dramatic Robert  Helpmann and Ashton himself were danced, respectively, by Anthony Dowell (the great Apollonian danseur of his generation, who then directed the company) and Wayne Sleep (a diminutive, ebullient artist who has not forgotten he was once a high-flying virtuoso). The present incumbents are perhaps a shade too outlandish, and of course the audience encourages them. Ashton himself achieved a nuanced portrayal–part Dickensian, part Chekovian–that was as touching as it was amusing.

Helpmann and Ashton himself were danced, respectively, by Anthony Dowell (the great Apollonian danseur of his generation, who then directed the company) and Wayne Sleep (a diminutive, ebullient artist who has not forgotten he was once a high-flying virtuoso). The present incumbents are perhaps a shade too outlandish, and of course the audience encourages them. Ashton himself achieved a nuanced portrayal–part Dickensian, part Chekovian–that was as touching as it was amusing.

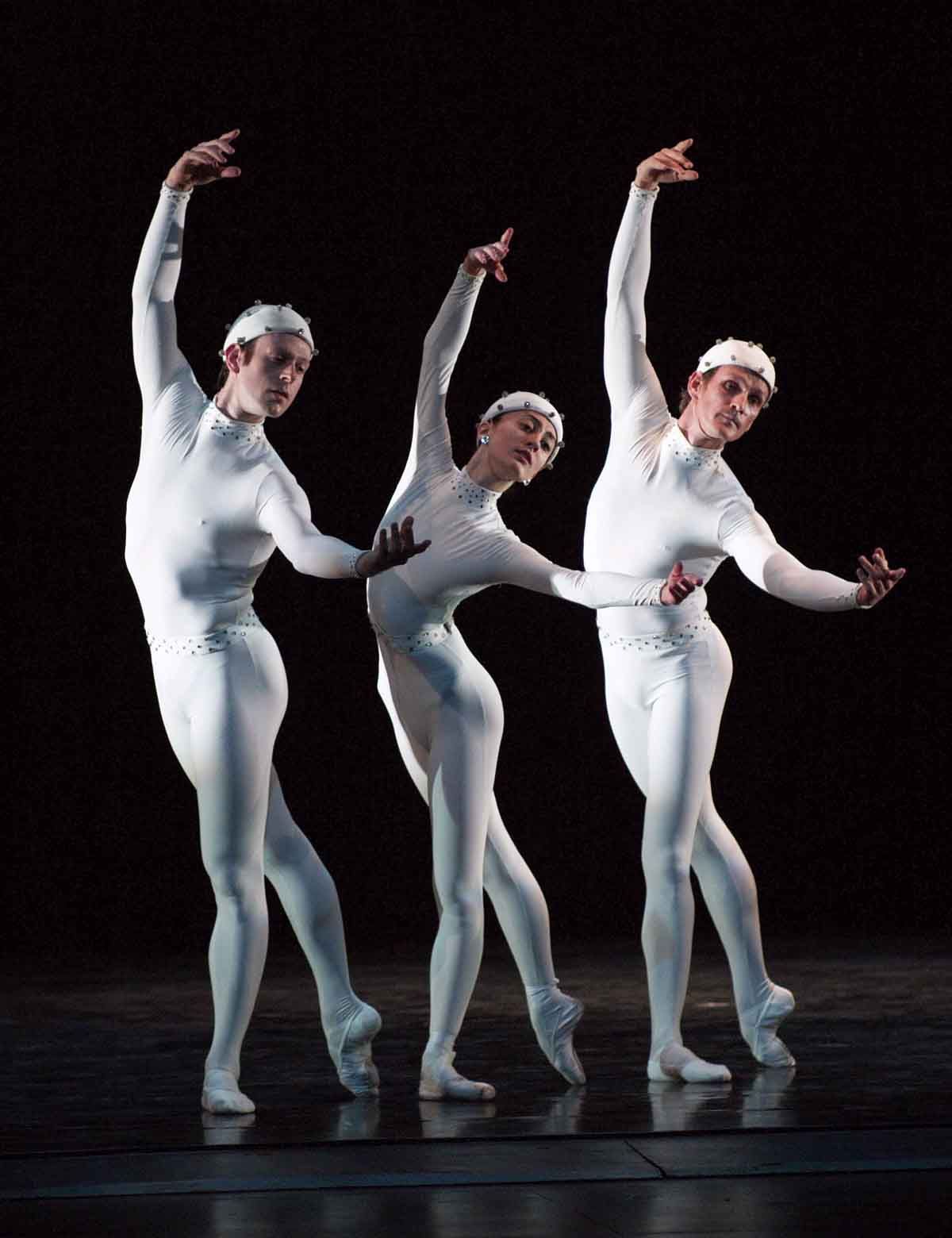

In descending hierarchic order, the Fairy Godmother, the four women representing the seasons, and the twelve representing the hours all embodied the Ashtonian aesthetic, from the contrapposto use of their torso and arms to the precision and delicacy of their footwork. Ashton’s choreography has many lessons to teach its dancers, and some splendidly compliant pupils were on view.

Photo credits: Dee Conway: In the Royal Ballet’s production of Frederick Ashton’s Cinderella: (1) Alina Cojocaru in the title role; Anthony Dowell (l) and Wayne Sleep as the Ugly Sisters.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

The second night of the Ashton Celebration featured two dances, both Birmingham Royal Ballet productions, in which the choreographer operated in his free-flowing “barefoot” vein, presumably with Isadora Duncan as his muse. The legendary primogenitor of modern dance was surely past her prime when the 17-year-old Ashton witnessed a handful of her performances in London, but she nevertheless made a tremendous and lasting impression on him—through her musicality, her sense of plastique, her voluptuous weighted quality, her resonance in stillness, and the sheer charismatic force of her conviction.

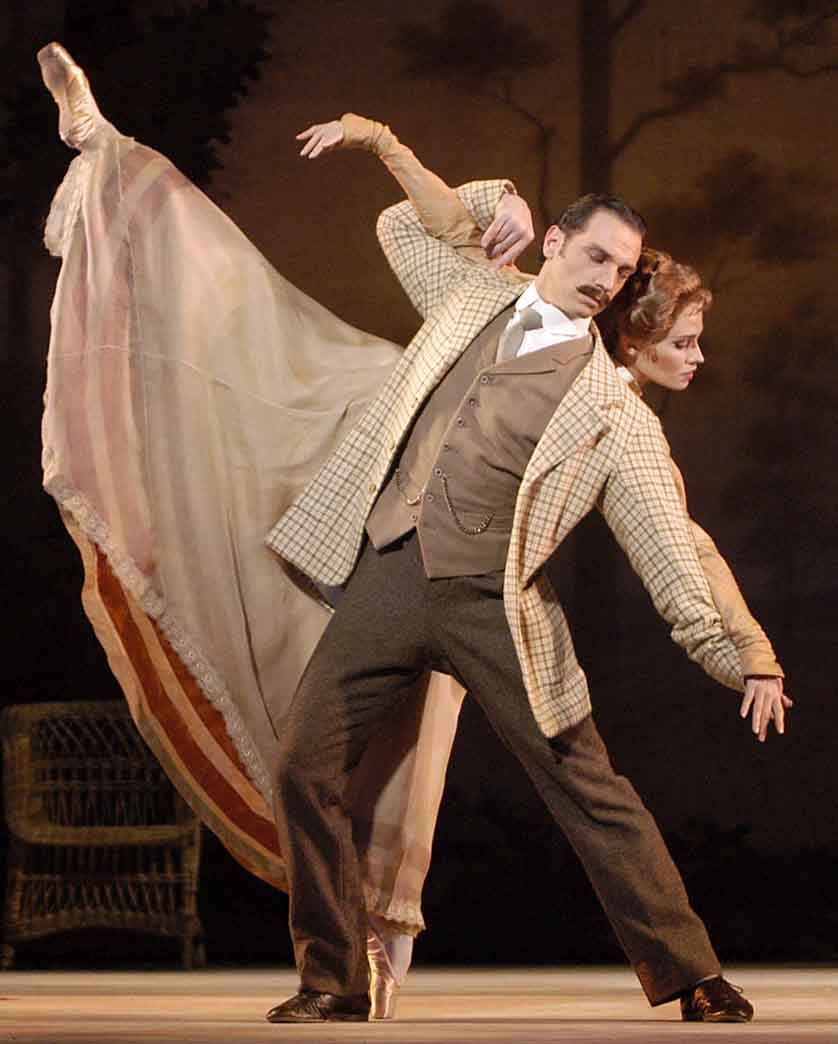

The second night of the Ashton Celebration featured two dances, both Birmingham Royal Ballet productions, in which the choreographer operated in his free-flowing “barefoot” vein, presumably with Isadora Duncan as his muse. The legendary primogenitor of modern dance was surely past her prime when the 17-year-old Ashton witnessed a handful of her performances in London, but she nevertheless made a tremendous and lasting impression on him—through her musicality, her sense of plastique, her voluptuous weighted quality, her resonance in stillness, and the sheer charismatic force of her conviction. The ballet is set to the Edward Elgar score from which it takes its name, a suite of musical character studies of individuals in the composer’s circle. Ashton places the action in Worcester in 1898, the locale and time of the score’s composition, in the house and adjacent garden where Elgar is surrounded by his near and dear: his care-filled constant wife; a man who is his heart’s comrade; several endearingly eccentric friends (whose very absurdity invites affection); several ladies whose relationship to Elgar, though intentionally kept enigmatic, suggests the many faces of love (a flirtatious child-woman, a serene mature one offering a sensuousness that needn’t ignite, an ephemeral muse), and an assorted flurry of neighbors and functionaries.

The ballet is set to the Edward Elgar score from which it takes its name, a suite of musical character studies of individuals in the composer’s circle. Ashton places the action in Worcester in 1898, the locale and time of the score’s composition, in the house and adjacent garden where Elgar is surrounded by his near and dear: his care-filled constant wife; a man who is his heart’s comrade; several endearingly eccentric friends (whose very absurdity invites affection); several ladies whose relationship to Elgar, though intentionally kept enigmatic, suggests the many faces of love (a flirtatious child-woman, a serene mature one offering a sensuousness that needn’t ignite, an ephemeral muse), and an assorted flurry of neighbors and functionaries.