The nostalgia factor looms large in Come Dance Me a Song, evoking a time when we were happier than we are now. Village Voice 8/30/04

ABDUCTING MOZART

Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker/Rosas / LaGuardia Concert Hall, NYC / August 25, 27, and 28, 2004

Mostly Mozart is looking to update its image. The annual summer festival at Lincoln Center, now in its 38th year, and its second under a new director, Louis Langrée, has ventured beyond pure concert work to what it terms—adopting corporate-world lingo—“new program initiatives.” One of these initiatives turns out to be theatrical presentation—specifically a couple of partnerships with dance. Last week, the Mark Morris Dance Group, in its third Mostly Mozart appearance, offered a fine program of regular repertory works set to Baroque music. This week came a more pointed (and far less successful) attempt to emphasize the connection between music and dance—a revival of the Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s 1992 Mozart/Concert Arias, un moto di gioia (a flash of joy). The time has by no means yet come to give the festival the disclaimer nickname Mostly Music, but the de Keersmaeker piece suggested—to me, anyway—that quality control might be more firmly exercised as the festival extends its parameters.

The score concocted for (let’s call it) Concert Arias is an assemblage that alternates short vocal and instrumental pieces from various points in Mozart’s career. The sung numbers, all for the soprano voice, were created for concerts or as insertions or replacements in the composer’s own operas and those of others. Some of them are profoundly beautiful; others are remarkable as tours de force.

The choreography for the piece tries and fails, dismally, to integrate its three singers (and pianoforte player) and its fourteen dancers onstage, requiring them to relate to one another as if they shared a mode of expression. I’m not saying categorically that this sort of thing can’t be done. Trisha Brown brought it off wonderfully in her staging of Monteverdi’s Orfeo (though less than wonderfully in her setting of the Schubert song cycle Winterreise). The undoable often becomes possible in the hands of great talent. Still, much as today’s soprano is physically far more svelte and fluent than her predecessors, she rarely shows to advantage when consorting with professional dancers. (You can see the absurdity of thinking she might, if you consider the dancers’ being asked to sing.) In Concert Arias, the interaction between singers and dancers is most often reduced to the sopranos’ being placed like fixed points amidst the dancers’ shenanigans and the male dancers’ annoying the singers with teasing flirtatious attentions barely worthy of high school boys.

As for the choreography for the dancers, I found it baffling and, after the first of two intermissionless hours, stupefying. Kate Mattingly’s essay in the house program quotes de Keersmaeker’s intention to deal with “the theme of love that can exist despite the distance between two people, even if the ultimate distance is death.” The words to the arias, also given in the house program, conjure up that theme almost generically, along with several others that testify to the vitality of romantic and erotic passion. But the choreography you actually get to see in this show is really about horsing around (lightly, and intermittently) and (deeply, and pervasively) incompatibility and hostility between the sexes.

Men and women segregate themselves in separate groups that often pace tensely, warily eyeing each other. Their inevitable conjoining is beset with frustration, occasionally downright antagonism. There seems to be nothing personal in their inability to couple with joy; their failure looks more like something fated, something in the air, a universal miasma that suffocates the spirit. Needless to say, this view of life is antithetical to the one evident in Mozart’s vocal music, where a gamut of emotions is expressed with, as it were, free will—indeed embraced as defining the human condition.

The dance language of de Keersmaeker’s piece, which is severely limited, ranges from shards of classical ballet that appear warped in their execution—inadvertently, I believe, for lack of expertise in that department—to motions suggesting jungle animals, as if to imply that human passions, even when sung about with infinite delicacy and sophistication as they are in Mozart, have to do with the primal and the wild.

Much of the choreography consists of falling to the floor; scuttling across it on the knees, beetle-style; and rolling around on it in ways that bode no good for the causes of love and human dignity, or, for that matter, aesthetic accomplishment. Early in the piece, the falls are largely confined to graceful ones—lyric spills derived, I’d guess, from Doris Humphrey’s technique. But as time moves (crawls, I should say) on, the situation seems to degrade and disintegrate, and the plunges do too.

Surprisingly, though a solo of rude gyrations repeats itself at intervals, the action never goes so far as to be transgressive. A duet that seems to serve as the climax of the prevalent amatory despair has some technical interest, as the man and woman involved are recumbent most of the time, rolling over each other and rolling away, only to initiate another round of approach and rejection. It seems to be a metaphor for the conflict between mutual desire or need and ingrained mutual opposition. Unfortunately it comes too late in the proceedings to revive a viewer’s interest.

Beside the surfeit of horizontal writhing, Concert Arias offers a half dozen sophomoric jokes that make you cringe; dancers who vocalize as they move, giggling, sighing, and sobbing; and avant-garde clichés that must have seemed tired by the time they were done a second time, decades ago, such as a performer’s skirting the perimeter of the dancing space with her eyes closed, threatening with every step to plunge into the abyss of the orchestra pit. This stuff, along with the portentous yet inconsequential pacing, is tedious enough in itself. Endlessly repeated, it’s intolerable.

Change of costume is a central element of de Keersmaeker’s show. The costumes themselves, by Rudy Sabounghi, are inventive and beautiful. Their theme? Sleek postmod irony meets Liaisons Dangereuses. In their contemporary urban-cool mood, the women pair drop-dead chic black suit jackets with micro-mini jet skirts, long stretches of bare leg, and footgear inspired by eighteenth-century fashion. (Not unexpectedly, the shoes eventually get used as props in bits of foot-fetishism.) For their retro mood, the ladies are assigned picturesquely wrecked (and movement-friendly) versions of eighteenth-century dress for high and low walks of life (the milkmaids are delicious!). The guys, though they remain barefoot (and bare shinned as well), have period gear to match the women’s—long lush jackets, embroidered weskits, lavishly loose white shirts with ballooning sleeves that double as nightshirts, and legwear that lies provocatively between pantaloon and trouser. The dancers spend a great deal of their time dressing and undressing (with obvious implications of erotic adventures), mixing and matching various pieces of both their own costumes and those of the opposite sex. While a costume maven like me will find this diverting, it’s still no substitute for dancing. For the record: The trio of sopranos wear ladylike variations on a theme of blue velvet, as if they’d explained to the saleswoman at Bendel, “Something for a classical music recital, you know. Elegant, but not too showy.”

The three admirable sopranos were Patrizia Biccirè, Anke Herrmann,

and Olga Pasichnyk; Steven Lubin was the man on the pianoforte; Gregory Vajda conducted the Orchestra of St. Luke. The dancers came from de Keersmaeker’s company, Rosas.

Photo credit: Rosas, Herman Sorgeloos: Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s Mozart/Concert Arias, un moto di gioia

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

WITHOUT WHOM

Mark Morris Dance Group / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / August 19 and 21, 2004

Typical Mark Morris! His company gets invited (for the third year running) to perform in Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival—where dancers rarely tread—and he weighs in with a program of four pieces, not a single one of them choreographed to a Mozart score. Instead, the bill consists of Marble Halls (from 1985, to Bach), A Lake (1991, Haydn), Jesu, Meine Freude (1993, Bach), and I Don’t Want to Love (1996, Monteverdi). Since I’ve written about each of these works closer to the time of its making, instead of talking here about choreography, I want to consider the second element that has always made the Mark Morris Dance Group extraordinary—its dancers.

From the start, Morris has gone in for nonconformity when it comes to the bodies he chooses to animate his work. Instead of selecting for uniformity and conventional notions of a physical ideal, he has regularly assembled a miniature motley society of the small, the stocky, the lushly ample, the tall-and-skinny beanpole type, the delicate, the blunt, and, yes, a few whose ballet teachers may have had high hopes of placing in one of those finalists-only classical companies that go by their initials. The flat-footed and those whom the gods of turn-out have not favored have their place with Morris, as do the fresh and frank American girl and the sultry glamour girl (Betty and Veronica, if you will), the beach hero and the fellow into whose face the beach hero kicks the sand. And of course the company has always been multi-ethnic—so thoroughly so that, simply by appearing, it defies tokenism, demonstrating that there are an infinite number of ways to be Caucasian, black, Asian, or a mix thereof.

Of course this fine assemblage couldn’t call itself a company—excuse me, a group—if its members didn’t have some key traits in common. What might they be? As Morris famously said in a Q & A session, “That’s a good question, and here is the answer.”

These dancers are acutely musical. Well, they’d have to be, given the fact that Morris is the most musical—and music-driven—choreographer currently at work in the Western world. To have them otherwise would be unbearable for him; he’d simply self-destruct.

They are wonderfully intelligent. I’m not talking about book learning here, though many of them have their share of it, but, rather, dance intelligence. In performance a dancer is making critical decisions about matters of timing and tone at every instant. To be sure, the choreographer has set the performer’s steps and gestures and is continually correcting and coaching the execution of that material—or appointing a deputy to do so. But much of what we think of as dancing—in other words, the interpretation as opposed to the part of choreography that’s capable of being notated—must be left open, flexible, if the results are not to look mechanical. That’s where dance intelligence comes in, making the choreographic score breathe. Morris’s dancers possess it in abundance.

In all their performances, they offer a full-bodied commitment to the work. These are not people who dance by half measures. Ever.

They have a magnificent sense of weight. To paraphrase Agnes de Mille on Martha Graham, they have taken the floor into their confidence. Yet, while gravity is their ally, every one of them knows how to jump, wrenching herself or himself from the earth to rejoice, triumphant, in the air for a moment and then to return—mind you, with equal pleasure—to native soil. Nevertheless, when the occasion requires it, they can be light and, what’s more, buoyant.

They allow themselves to be vulnerable. I don’t mean to look vulnerable, but to be vulnerable. This lends their dancing, as appropriate, great drama and great pathos. They are—is this a corollary?—capable, equally, of ferocity and gentleness.

They’re not addicted to harmony. Most of them have been blessed with a natural grace that has, certainly, been amplified by years of dance training. Some of them, though, retain aspects of awkwardness, and Morris honors this quality in his choreography, makes much of it, in fact, and reintroduces it to the smoother performers, because he knows that to be awkward is to be human.

They’re expressive without even a shard of narrative.

Their dancing has terrific texture. Part of this is due, I imagine, to the fact that many of them are not in the first-youth decade of their careers but rather in their thirties, even forties, so their dancing benefits from both their dance experience and their life experience.

And, indeed, these dancers remind you of real people. Morris sees to it—I’ve witnessed this at rehearsals—that they move without affectation. Routinely, they de-emphasize the artifice that is, after all, essential to their trade. Their mode of self-presentation is the very opposite of the high stylization that practitioners of classical ballet and Martha Graham’s brood revel in. Instead of being icons of the ideal, Morris’s dancers are icons of the norm. This helps the audience identify with them, and thereby with the situations—the predicaments and exultations—that Morris’s choreography proposes.

Over the last two plus decades Morris has gradually gone from making dances on the people who were simply available to him–as he himself said, his friends—to choreographing on formidable pros. Today he chooses his dancers from an enormous talent pool—people are clamoring to dance with him, they audition by the hundreds—and their anatomy is sleeker, their technique more proficient than the old gang’s. What’s more, Morris, clearly their senior in years, now rarely dances among them. So no one on the stage or in the audience would claim that the current dancers are choreographer’s friends. Oddly and happily, they have come to seem like the viewers’ friends.

I know, I haven’t named names here. Two decades’ worth of performers have contributed to my impression of the remarkable kind of dancer the Morris troupe welcomes and hones. People tend to stick with this company for long stints, too, and I’ve had the pleasure, over the years, of watching them mature. Doing all of them justice would require a book. Neither do I care to single out just a few who are presently with the company while neglecting equally worthy others. But what about just listing the current crew?—you know, for the record. Here goes: Craig Biesecker, Joe Bowie, Charlton Boyd, Amber Darragh, Rita Donahue, Marjorie Folkman, Lauren Grant, John Heginbotham, David Leventhal, Bradon McDonald, Gregory Nuber, Maile Okamura, June Omura, Matthew Rose, Noah Vinson, Julie Worden, Michelle Yard. When Morris takes his curtain call at the end of a concert, he always bows to the dancers first. As well he might.

Photo credit: Robbie Jack: (l. to r.) Joe Bowie, Michelle Yard, and Matthew Rose in Mark Morris’s I Don’t Want to Love

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Universal Ballet of Korea

By far the most agreeable part of the Universal Ballet of Korea’s “Romeo and Juliet” was the young company’s personable dancers. Village Voice 8/17/04

FROGGIE BOTTOM

The Frogs / Vivian Beaumont Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 22 – October 10, 2004

I can’t imagine why Susan Stroman—best known as the choreographer of Broadway shows, sometime provider of diversions for highbrow sites like New York City Ballet and the Martha Graham Dance Company—didn’t make dance a stronger element as director and choreographer of The Frogs. Surely her collaborators on this entertainment, Nathan Lane (libretto, lead role) and Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics), knew what she does best.

The show itself is a disheveled affair. A timeline may help explain how it emerged in its present form.

405 B.C. / Aristophanes (the ancient Greeks’ king of comedy) writes The Frogs, in which Dionysus, god of wine and drama, crosses the fateful River Styx into Hades. His errand is to bring back from the dead a playwright whose words might be powerful enough to elevate the state of the theater and the minds of the Athens citizenry, which neither thinks nor acts, despite its social and political problems. A pair of his culture’s key tragedians, Aeschylus and Euripides, vie for his attention through a duel in quotations.

1941 / Burt Shevelove stages his adaptation of the play, updating the plotline, with William Shakespeare and George Bernard Shaw replacing the Great Greeks.

1974 / Shevelove resurrects his show, coopting Stephen Sondheim (with whom he’d partnered on A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum) to turn it into a musical. The production is staged in and around the Olympics-sized swimming pool at Yale, which also happens to have a renowned drama school. Some of the students who participate in the production are Meryl Streep, Sigourney Weaver, and Christopher Durang—who go on to be seriously famous. It might have been best to leave wet enough alone. But no . . .

2002 / Nathan (The Producers) Lane, who has had a hungry eye on the 1974 show for nearly a quarter-century, hosts and performs the leading role in an abbreviated concert version of it.

2004 / Lane re-revises the Shevelove libretto extensively. Sondheim is prevailed upon to write a half dozen additional songs. Susan Stroman, as indicated, is signed on to direct and choreograph. The current Frogs opens—to reviews that are mixed, to put it graciously—as part of this year’s Lincoln Center Festival.

A funny thing or two has happened to the original Frogs on its way to the present. It has grown increasingly politicized. The creatures who give the play its title have evolved from a simple chorus of amphibians that serenades Dionysus on his disquieting ferryboat ride into today’s know nothing, say nothing, do nothing populace, lulled by leaders of dubious qualifications to okay “a war we shouldn’t even be in.” The present version seems to fancy itself something of a left-leaning rabble-rouser, destined not to tour to the Red States.

At the same time, the latter-day Frogs has become more theatrically ingenuous. In the original, the Aeschylus-Euripides quotation contest is a parody; Aristophanes wrote all the lines. When the switch was made to Shakespeare-Shaw, the quotes were plucked (by a bunch of students) straight from the British playwrights’ texts. In the current version, the contest is reduced to a ludicrously unsophisticated argument between mind (represented by the witty, acerbic Shaw, who tells us what we should think) and heart (represented by the mellifluously humane Shakespeare, who knows how we feel). Guess who wins.

As for the ramshackle plot and the low jokes of the libretto in its present form, these admittedly have some roots in the original, but the tone of the whole affair has shifted to the point where I suspect Aristophanes himself—should he get a day pass out of Hades—might drop in at the Beaumont and declare “It’s Greek to me.”

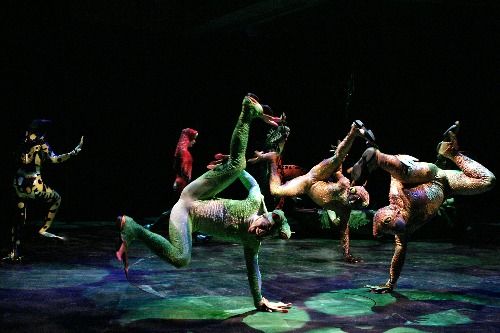

Now about this business of the dancing . . . Essentially, there isn’t any for what feels like the first quarter of the show, unless you count an octet in Greek tunics performing a sequence of stop-motion poses that parody the postures depicted with such grace on Grecian urns. Eventually Dionysus gets to the Styx and is traumatized—as we are amused—by the river’s population of frogs. These aquatic squatter-jumpers are played by dancers with formidable gymnastic prowess. Costumed in vivid body stockings and flippers inspired by dart poison frogs (a troupe of which is currently playing the American Museum of Natural History, they see no shame either in artificially enhancing their prowess via bungee cords or in condescending to a game of leapfrog. They dabble in ballet, too; if you haven’t seen a pair of amphibians doggedly churning out fouettés, now’s your chance.

In Act II, the Three Graces turn out to be a trio of pretty-as-hell, well-endowed, scantily clad aerialists contorting their pulchritudinous bods around long swaths of fabric that hang in loops from the flies. Once arrived in Hades, Dionysius and his trusty slave attend some revels thoroughly saturated with wine, women, song—and dancing that couldn’t be more trite. It’s as if the advancements in choreography for the Broadway musical made by Jerome Robbins had never occurred. In the same vein, a cluster of Shavian groupies does only routine vaudeville stuff. The regrettable paucity of dance in The Frogs is revealed most clearly in the show’s climax: The battle of the quotations is simply words, words, words, with the competing playwrights ringed by ten cast members who just sit and listen.

I have never taken much joy even in Stroman’s best choreography. The more frenetic its exuberance gets, the less I believe in the thrills it’s promoting. But I’ll concede that it has a verve that many find cheering—uplifting, even. And more of what I take to be Stroman’s equation of movement with the life force would certainly be welcome on this occasion.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Frogs in The Frogs.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Von Ussar Danceworks; Michiyo Sato and Dancers

Astrid von Ussar uses juicy, ferocious movement to create dances exploring relationships of the heart; Michiyo Sato summons a polyglot vocabulary and a gently feminist aproach to treat issues rooted in the history of her native Japan. Village Voice 8/11/04

SWEAR NOT BY THE MOON

Universal Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 30 – 31, 2004

Korea is a land with its own venerable dance traditions. Classical ballet, which had taken root there by the 1960s, was a distinctly foreign import (just as it once was in the U.S.). The major influence on the development of ballet in Korea has come from Russian practitioners who brought it a Russian approach to technique and a Russian repertory—nineteenth-century classics like Swan Lake and twentieth-century works in the Soviet style. A native style and a repertory that springs from native culture is budding, possibly, but when the 20-year old Universal Ballet chose a vehicle for its American tour this summer, it relied on Romeo and Juliet, in a version choreographed by Oleg Vinogradov, the company’s present artistic director, who led the Kirov Ballet for over two decades. (The general director of the Universal Ballet is Julia Moon, one of its former ballerinas and the daughter-in-law of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon and his wife, who are billed as founders and patrons of the company. I’m not about to tackle the issue of the Universal Ballet’s connection to the Unification Church, but my colleague Mindy Aloff touched on the subject in a recent interview with Moon for the DanceView Times. An earlier pair of articles by Hilary Ostlere for Dance Magazine, further elucidates the relationship.)

Vinogradov’s take on Romeo and Juliet, created in Novosibirsk, Siberia, back in 1965, unfortunately has little to recommend it, certainly not the corny new ending recently tacked on. Vinogradov makes a hash of the familiar Prokofiev score—presumably to serve the libretto he’s concocted from Shakespeare’s version of the tale and his claimed desire to emphasize dancing over pantomime. He has also, to his peril, taken liberties with Shakespeare’s cast of characters. Conspicuously missing are Benvolio (replaced by a few anonymous friends-to-Romeo) and Juliet’s Nurse (whose absence gravely diminishes our understanding of Juliet’s circumstances). Added are the wholly unnecessary figure of Death—surely de trop in a narrative clearly saturated with morbidity and concerning realistic, not symbolic, characters—and a crew of modern young sweethearts in jeans (straight out of the Joffrey Ballet of the seventies), reverently lighting their votive candles at Romeo and Juliet’s tomb and spilling from stage out to the audience as the curtain falls.

In style, the choreography is a little Soviet exalted realism, a little Classic Comics simplistic vividness. If the dancing seems to have no impulse, no drive, no phrasing, it’s because the choreography doesn’t demand such things—indeed, appears to have no idea they exist. And the dancers haven’t been encouraged to make up for the deficiency. The music keeps issuing urgent reminders on the subject, but no one, apart from the audience, hears them.

In the course of the proceedings, some very peculiar occurrences stand out. On no less than four occasions, when Romeo has Juliet artfully cantilevered from his body, making her a piece of sculpture in the air (this is no time to protest that you dislike this sort of thing), he lifts one leg to make the feat even more difficult. Of course it then looks absurd and detracts from any idea of ecstasy Vinogradov means his lovers to convey. And then there’s the scene in which Juliet’s father so gives way to his anger over her disobedience in refusing the suitor he’s chosen for her that he resorts to a violent physical abuse—throwing her to the floor and stomping on her ribcage, as I recall, or was it her pelvis?—that’s entirely out of keeping with the intimate, interior scenes of the ballet as opposed to its “outdoor” brawls. What do these two instances have in common? Nothing (which makes them all the more disconcerting) or perhaps simply a mind-boggling absence of taste.

Despite these failings, the handling of the masses is fine indeed, charged with vitality and a symbolic dimension as well. At Juliet’s coming out party, for instance, the aristocratic guests line up in cross-stage rows, assuming a series of frozen poses. In this way, they form a human sculptural corridor through which Romeo and Juliet waft after they fall in love at first sight—a corridor, it soon becomes clear, in which they’re spied upon by society at large and from which they cannot escape.

The dancing per se is done a disservice first by choreography that refuses to let it flow and then, it would seem, by coaching that hasn’t once suggested it be allowed to breathe. But, though the company’s overall technical standard comes nowhere near that set by the major classical companies we see in New York, it is respectable and what one might call, given the comparative youth of the company, promising.

Hye-Min Hwang, who was the opening-night Juliet, is appropriately delicate and willowy in her build, though not as refined in her dancing. Eventually, seemingly through sheer hard labor, she works herself up to an anguish that’s believable.

Jae-Yong Ohm, as Romeo, is a sweet prince, a charmer, but oddly lacking in the impulsive passion essential to the character. He has, instead, a whimsical quality that’s almost asexual, perfect for a commedia dell’arte Harlequin. Oddly enough, Paris is no more suitable as a match. He looks like that famously languid young Renaissance aristocrat drawn by Nicholas Hilliard and behaves with well-bred reticence to Juliet as if, entirely absorbed in his own lovely image, he doesn’t much care if he gets to marry her or not.

Jae-Won Hwang, who has the compact build and raw energy of a demi-caractère dancer, makes a swell Tybalt, and the senior character artist Igor Soloviev, as Friar Laurence, is straight out of Dostoevsky. Granted, this characterization is entirely at odds with the rest of the production, but the rest of the production is such a hodge-podge anyway, the little Russian star turn is entirely welcome.

The sets and costumes, by the Russian-bred designers Simon Pastukh and Galina Solovieva, respectively, are the most memorable—and expressive—part of the show, the element that makes it undeniably worth seeing. The basic set is solidly architectural, serving both as exterior (with the community’s meeting place anchored upstage first by an imposing equestrian statue, then by a stage within the stage for a pointed play within the play) and interior (now anchored by the altar in Friar Lawrence’s church, then by Juliet’s fateful bed). It has the confident air of being historically exact and is, at the same time, laden with atmosphere, making you feel you’re in a real place and, what’s more, a place haunted by everything that has happened in it up to the present moment. The costumes, apart from Juliet’s virginal gowns, rightly suggest the flamboyance and excess of wealth—an extravagant beauty that is, at heart, evil. The ballroom get-up of the Capulets and their guests, to cite just one example, is nothing short of sensational—very cloth-of-gold against jewel tones, topped by fantastic headdresses combining extravagant hanks of hair with the plumage of exotic birds. To date, the main venues for these scenic artists’ work seem to have been Russia, Korea, and the American Midwest. London, Paris, and New York might profitably pay them greater attention.

Photo: Kwang-Jin Chung: Members of the Universal Ballet in Oleg Vinogradov’s Romeo and Juliet

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

GOODBYE, ARGENTINA

Boccatango / Joyce Theater, NYC / July 26 – August 12, 2004

The New York dance audience knows Julio Bocca best from his star turns with American Ballet Theatre. These days, he’s also starring in Boccatango, teamed with members of Ballet Argentino, the company he leads back home in Buenos Aires. This touring vehicle is neither classical ballet nor tango, though. Rather, it’s a show in which the choreographer Ana Maria Stekelman exploits both genres (as well as modern dance and jazz) to produce an entertainment more fit for a cabaret than the concert stage.

Item: Bocca, in a sheer black singlet and tango trousers, gets cozy with a stark black table, using it as a support for some gymnastic skirmishing, as a cage, and as a surface from which to cantilever himself into space. Just when you’re belatedly getting the idea that it’s his bed, and that his antics indicate his sexual fantasies, along comes the girl of his dreams—an exquisitely svelte little thing, all flexibility and precision, without a smidgen of soul. After she struts her stuff, however, she’s claimed by a different guy, a big, attractively thuggish type, their doings half apache dance, half something we’re often treated to by the Ailey company.

Item: Now it’s Bocca’s turn to get the gal. No need to cry for him, Argentina. A more mature woman than the earlier vision arrives, clad for after-hours office work, you might say, in a black tailored suit. She then strips it off to dance with Our Hero in nothing but (working downward) a bikini bra, a thong, and sheer black thigh-high stockings. Bocca’s got nothing on now but his abbreviated skivvies, and before long she decides to keep him company in his bare-chested state. (At this point, the lighting dims to that low orangey glow that indicates sensitivity to the standards of the local decency squad.) Like most fantasies, the lady doesn’t last long.

Item: Dead center on an otherwise dark stage, an overhead light beams down on a way tall raw-wood ladder. Just in case you weren’t already saying “uh-oh” to this set-up, a dry ice fog has rolled in from the wings. It disperses to reveal the bare-chested Bocca lying supine under the ladder, looking as if he’s been sacrificed, perhaps martyred. But no, he rises, and you notice he’s wearing a pair of tough gloves to protect his hands for the upcoming feats of strength, balance, and sheer nerve he will attempt on the rickety prop. So in a very few minutes we go from implications of New Testament agony to the modest acrobatic achievements of a small traveling circus. What this may have to do with dancing is anybody’s guess.

As for the rest of the program, there are group numbers, in some of which the fact that the tango, historically, used male-male partnering is co-opted to create a sensation. There are myriad opportunities throughout (perhaps a few too many) for Bocca to display his grand jeté—ballet’s familiar striding-the-air leap, which he makes sharp and buoyant at the same time—and his whiz-bang turns. There is, predictably, a dance involving chairs (clearly bought in a job lot with the table we saw early on). There are even a couple of comic turns (don’t ask, I beg you, I’m doing my best to forget).

All this (and more, mercilessly more) has musical accompaniment from a small group of instrumentalists (bandoneon player included, natch) and a pair of vocalists—the lady in question doing a serviceable job that is a shade pathetic, the gentleman lacking both the voice and the personal charisma that is necessary to his trade.

The most extraordinary thing about this dismaying show is that it’s the very antithesis of the tango, a dance form celebrated for its sultry, sinuous rhythms; its sensuous range of emotion, from the raw to the subtle and mysterious; its ability to evoke a mood of nostalgia, even about the present. Boccatango is sanitized and, in every possible way, over-miked.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Heidi Latsky Dance

Latsky personifies that state every dancer aspires to–in which intent and execution are one. Village Voice 7/26/04

GOING TO EXTREMES

Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Heisei Nakamura-Za / Damrosch Park, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 17-25, 2004

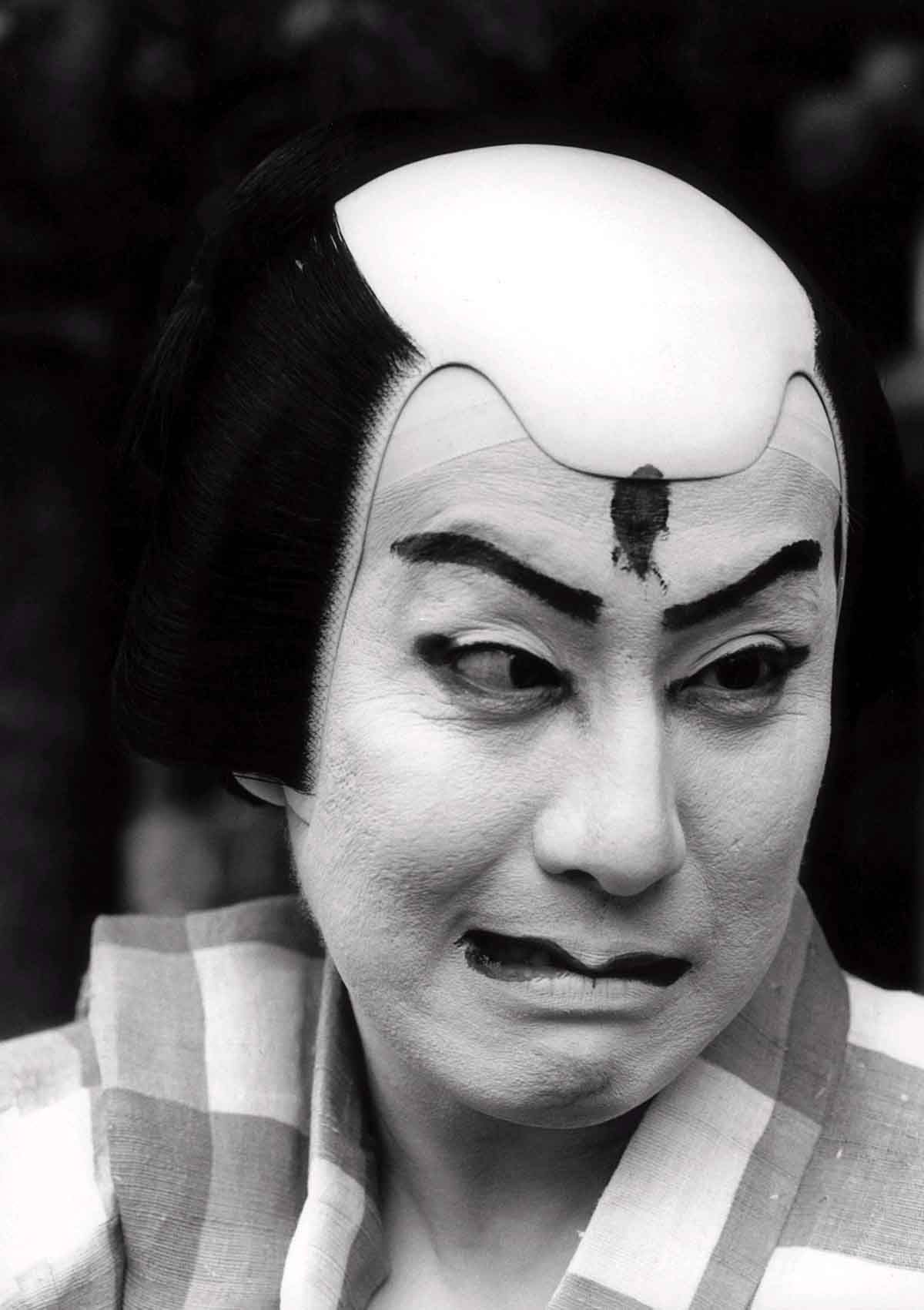

In a temporary theater in Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park designed to replicate a traditional venue for Kabuki performance, Japan’s Heisei Nakamura-za company condensed to three hours a play that takes a full day to unfold in its unabridged state. Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka) encompasses domestic comedy and domestic tragedy, low humor and high melodrama, keen psychological observation and spectacular combat—all evoked via the vividly stylized means of an art form that’s been riveting audiences for over 400 years. Despite the damage done to the story by compression (surely the original paid more attention to the soulful highborn youth at the center of the plot); despite the fact that the only performance I could get admission to was a dress rehearsal at which the simultaneous translation broke off halfway through; despite my uneasy feeling that I was seeing tradition much influenced by the age of video games, two scenes promise to stay with me for a good long time.

In a temporary theater in Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park designed to replicate a traditional venue for Kabuki performance, Japan’s Heisei Nakamura-za company condensed to three hours a play that takes a full day to unfold in its unabridged state. Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka) encompasses domestic comedy and domestic tragedy, low humor and high melodrama, keen psychological observation and spectacular combat—all evoked via the vividly stylized means of an art form that’s been riveting audiences for over 400 years. Despite the damage done to the story by compression (surely the original paid more attention to the soulful highborn youth at the center of the plot); despite the fact that the only performance I could get admission to was a dress rehearsal at which the simultaneous translation broke off halfway through; despite my uneasy feeling that I was seeing tradition much influenced by the age of video games, two scenes promise to stay with me for a good long time.

In one, a sympathetic woman volunteers to serve as caretaker to the princeling who is hiding out for reasons too convoluted to record here. An objection arises: What if this woman’s youth and beauty should tempt the young man to sexual imprudence? (In truth, the lady in question is not so much nubile as the picture of matronly elegance, her bulky figure clad in a black kimono elegantly offset by touches of sienna and red, her soft, plump fingers manipulating a matching lacquered parasol—but we theatergoers know how to suspend our disbelief.) With furrowed brow and a sorrowful twist to her mouth, the woman ponders the problem. Then, seizing a taper from the burning brazier at her side, she heroically it presses to her cheek. When she removes it, the smooth white flesh is marred with a bloody wound. (The audience knows this is just a make-up trick, but gasps in horror anyway, because the performer makes the moment thrill with reality.) Her hands, all delicate agitation at the wrists, flutter with tremors of pain as she holds a cloth to the crimson streak. Offered a hand mirror, she confronts her scarred image, and now her whole body pulses with shock. Her face twists in her first voiced response to the event as if the burn had not merely ruined the outer layer of skin but also reached deep into muscle. “The face her parents gave her,” she declares, is now scarred for life, and she wants the onstage witnesses to know how much that disfigurement means to her. So, after the self-mutilating action that’s sensational in its brutality and courage plus the exquisitely calibrated physical detail of its aftermath, we paying voyeurs get to savor the irony of her verbally requesting understanding from her fellow characters in the play when she has already secured our empathy through the emotional intensity of her actions. From this scene, too, comes the telling line, “There’s no sense in matters of the heart, and the unexpected can always happen.”

Another, more extended passage, works as the centerpiece of the play. Danshichi, the tale’s chief character, quick to use force as reason, confronts his father-in-law, Giheiji, a low-life whose corruption is symbolized by his wizened body, filthy ragged clothes, and truly deplorable teeth. No paragon of everyday honor himself, Danshichi uses a fake bribe to make Giheiji right the most urgent of his numerous wrongs. Once Giheiji realizes he’s been duped, he heaps a torrent of abuse (some of it frankly scatological) on his son-in-law, taunting Danshichi into attacking him physically, reminding him all the while that the punishment for killing a parent is death.

Slowly the scene slips from rough comedy to a moral and emotional seriousness that belongs to poetry. And in the course of this progression, the scene, which can be imagined to have started at sundown, slowly darkens into night. The traditional black-veiled stagehands of Japanese theater move in with translucent lanterns extended on long poles, following the swiftly moving protagonists to illuminate their bodies and faces.

The ensuing battle—a tour de force blending sword swipes, body-to-body grappling, and profound psychological conflict that prefigures Macbeth’s—is so protracted it becomes hallucinatory. Danshichi, who has on his side a brute physical advantage and the single available weapon, is reluctant to commit a murder he’s sure both the law and the heavens will curse. More and more blood flows. The combatants’ clothing is gradually stripped away, and their hair hangs wild. The illumination grows increasingly fugitive, sometimes reduced to a single beam held up to a single crazed face. Eventually it becomes so dim that the frenzied action takes on the insubstantial air of a dream, then plunges into “endless night.” In the obscurity, the skeletal old man falls into a pool of muddy water and rises from it a dripping brown specter—not yet dead but already a ghost. Now, finally, Danshichi summons the courage (or desperation) to put his victim down forever and poses, briefly floodlit, a victor himself in extremis, passing his sword through a lantern’s flame, hysterically sloshing himself with buckets of water, as if, with these rituals, he might repossess his soul.

Have I neglected to mention that the self-sacrificing woman and the guilt-ridden warrior were played by the same actor? He’s Nakamura Kankuro V, a 48-year-old scion of a family that has been practicing the art of Kabuki since the 17th century. He does honor to his heritage.

Photo: Nakamura Kankuro V in Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka)

© 2004 Tobi Tobias