Kourtney Rutherford, whose résumé adds three years in construction work to familiar dance and drama credits, spins a goofy, macabre tale in a half-built tract house set. Village Voice 10/19/04

Octavia Cup Dance Theatre

Laura Ward’s new, ambitious, bilingually titled Enredaderas: Entanglemnts opts for excess at every turn. Village Voice 10/19/04

PULLING STRINGS

Basil Twist: Symphonie Fantastique / Dodger Stages, NYC / ongoing

Mark Dendy: choreography for Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / October 8, 11, 15, 18, and 21, 2004; April 5, 13, 16, 20, and 23, 2005

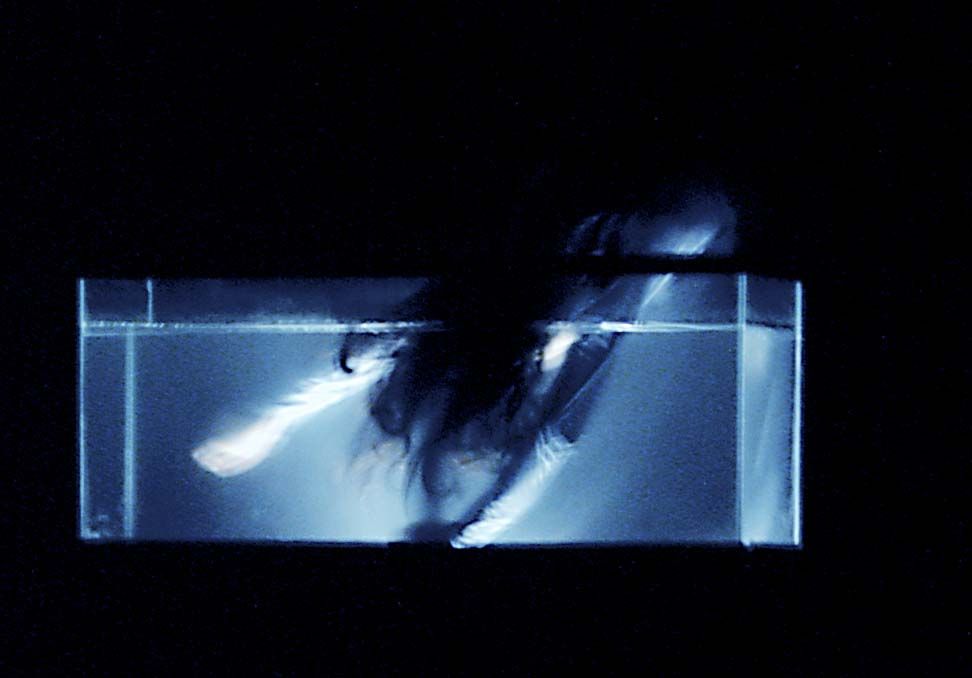

The idea of Basil Twist’s Symphonie Fantastique is magical: You’re sitting in this small neo-Bauhaus black-box theater—one of five spaces at the new, ingenious Dodger Stages complex on West 50th Street. And you’re staring in anticipation at an oversize fish tank or, if you will, a Lilliputian aquarium. Its contents are concealed for the moment by the sort of lavish looped red curtain (or is it a picture or projection of one?) typical of yesteryear’s opera houses.

Up the curtain goes to reveal water (defined by clusters of giddy air bubbles) and its inhabitants. You’ve been promised puppets, and marionetteers—six of them, including Twist, and two swings—are indeed listed in the house program with impressive credentials such as training at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts de la Marionette. You can even see a few of the strings and wires being used by the dexterous hidden manipulators. But this is no Punch and Judy, no Salzburg Marionette Theatre, no Muppets, no Bunraku. Twist is on the trail of abstract puppetry, and his “characters” are wisps of cloth, feathers, and tinsel strips.

The first puppet on is a smallish swath of white fabric that leads a turbulent life in its glassed-enclosed sea and seems to think it can fly as well. Watch it carefully. It will emerge as the show’s protagonist, a brave, optimistic little fellow with whom, I believe, the viewer is meant to identify. The personal-size sea will, accordingly, come to stand for the universe. For the sake of convenience, I’ll call our hero Salamander (Sal, on better acquaintance), since he often assumes the shape of one.

It turns out that Sal has a cluster of look-alike friends as well a capability to change color that gives him the air of a psychedelic chameleon. Alas, the trouble with Sal’s effects is that they could be rendered on video with no loss of impact or created electronically from scratch. I’m wondering if the several children in the audience recognize the difference between the live show they’re watching and the fare regularly served up to them on TV. I can see how the grown-ups might regard the performance as nothing more than a screen-saver with pretensions to Higher Things. Similarly, the intermittent bubble effects, though they have their charm, are duplicated and topped by many an exuberantly programmed public fountain, such as the one delighting and mesmerizing spectators ogling it from Greek-amphitheater bleachers at the newly constructed plaza fronting the Brooklyn Museum.

After running Sal through his repertoire, Twist introduces other players: feathery plumes (which shed a little, so that they enjoy an accidental afterlife) and other filaments, like thin, translucent ribbons. They’re ravishing, but by the time they’ve come and gone—certainly before they come again—the viewer may be admitting that it’s hard to engage with marionettes that don’t represent people or animals, if only in fantasy forms. Inanimate objects, animated though they may be by their keepers, are pretty much incapable of narrative and its offspring, drama—unless, of course, they’re anthropomorphized (as I’m guilty of doing, naming Sal). One-third of the way through the hour-long show, Twist’s material begins to look merely like eye candy, the idea of it far more compelling than the execution and the result.

No doubt Twist himself recognized the problem and, applying an obvious remedy, added the attention-getting element of apocalypse—or at least enough hints of it to keep his viewers alert. First he sets the scene, taking us to a midnight blue forest glowing with tiny specks of flickering light, as if it had been invaded by fireflies. Or is he, perhaps, showing us a single tree, bedecked with tinsel and inexplicably submerged in a dark lake? Beauty, mystery, and menace; the atmosphere serves as a prelude. From here on in, Twist counts heavily on the audience’s impulse to create story—and thus meaning—where none exists, at least at the literal level. The phenomenon is common. Most people can’t bear looking at things they can’t identify. Think of how often abstract painting, sculpture, and dance is greeted by a plaintive or hostile “What is it?”

Stubbornly enigmatic, Twist moves us to a shades-of-gray Nowheresville punctuated by hazy beams of light that suggest outer space and punches the action right up to Star Wars level. Small, brave Sal returns to thrash his way through the fuzzy, shifting crosshairs, attended in time by his loyal pals. The creature’s earlier idyll of indolent, graceful swimming that segues into ecstatic flight becomes a mere memory of calm before the storm. Swirling himself into a roll, Sal resembles an angry little cyclone. And now an ominous patch of inky threads invades the silvery space like a cancer, devouring or blotting out huge segments of the once-upon-a-time peaceable kingdom. Hope is not quite abandoned yet; the section concludes with the appearance of a portentous glowing speck surrounded by smoke, like a match ignited in darkness.

Next, a scene of vibrating cylinders. Remember Claes Oldenburg’s outsize soft sculptures of small, hard, everyday objects? Like that—if he’d done cigarettes. A pair of these flexible columns (in ironic pastel tints) invades the foreground from opposite sides like self-important opposing leaders, confronts but doesn’t take that fatal last step into combat. Each is then portentously seconded by a second. The threat comes to nothing. Generals and lieutenants retreat to their own sides only to repeat the inconclusive face-off. In the background, a close-packed line of them—let’s call them The People—trembles. It looks like politics as usual, but this stuff is punctuated by intermittent fires, green on one side, red on the other. And our innocent salamander beams straight into the conflagration and is destroyed.

And so it goes, the same basic elements used in increasingly agitated and elaborate ways, accompanied by Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, conveyed by a sound system evidently so primitive it has only two modes: OFF and VERY LOUD. I must say the music supports the visual antics, lending them a drama of danger, conflict, and bliss they might not otherwise convey so clearly.

Maybe it’s just me, subjected to too many excursions to the planetarium, first with small children my age, then with my own children, and then with my grands, but Twist’s show reminds me of those darkened-auditorium displays in which the nature of the universe is depicted in visuals that are essentially so abstract, I slip almost immediately into a stupor. Others have certainly reacted otherwise to Symphonie Fantastique. When the show was first done in 1998, it was all the rage with the downtown crowd and garnered both an Obie award and a Drama Desk nomination. And I haven’t given up on Twist. He’s preparing a new show, Dogugaeshi, based on esoteric Japanese puppetry traditions now threatened with extinction. Japan Society will present it November 18-23. Given my susceptibility to Japanese art and to puppetry, with its beguiling combination of the sophisticated and the ingenuous, it sounds like my kind of show.

The fall season in New York was full of puppet-driven productions, the most elaborate of them being the Metropolitan Opera’s new rendition of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute). Its mastermind was Julie Taymor—an opera director long before The Lion King made her name a household word—who was responsible for the overall concept, the costumes, and, with Michael Curry, the puppetry. Gregory Tsypin did the overbearing phantasmagoric sets. The puppet effects are a bit much, too. One patron hardly exaggerated when he claimed that the overload of visual stimuli prevented him from hearing the singing. Mark Dendy got the choreography credit. I’d be happy to follow the dictates of my job description and comment on his work—if only I could figure out what he did.

Nearly all of the movement interest belongs to the puppets, manipulated by an agile crew shrouded in black: an enormous dragon breathing fire (if not smoke) who nearly fells the princely hero, and requires at least ten deft attendants; a gaudy, avian flock fluttering on long willowy sticks to surround and tantalize the bird-catcher Papageno; a pack of polar bears (the best item in the show) that prove to be kites, inflating to full size and power as they’re guided aloft, cloth miraculously becoming flesh and muscle, then collapsing like melting marshmallow; and (unworthy of the occasion) a feast of flying food. Where did Dendy’s work come in? Was he responsible for the predictable patterns these objects create in the air? The delight, where it exists, lies in the objects themselves, not their traffic patterns. Presumably, Dendy choreographed the scene in which some absurdly long-legged birds, including several of the flamingo persuasion, offer a Vegas riff on Swan Lake, but this stuff is so routine, I wonder if some irony was intended, then only feebly resolved.

Throughout the production, the puppets, the costumes, and the sets conspire too blatantly to overwhelm the spectator. The puppet effects add to their sins by teetering on the edge of the Abyss of Cuteness, revealing a shameless cousinship with the world of Disney. As a dance critic, I found the most fascinating aspect of the evening to be the sight of human bodies going through pedestrian or theatrically stylized movements with only minimal visceral impulse and fluency, performing rote gestures while—as if emanating from another body entirely—the voice spoke worlds, rendering every idea radiant with feeling.

Photo credit: Carol Rosegg: Basil Twist’s Symphonie Fantastique

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Dancenow/NYC

ELEMENTS OF STYLE

Johannes Wieland / Diane von Furstenberg the Theatre, NYC / October 7-10, 2004

Johannes Wieland opened his recent concert with his 2002 Parietal Region, which, for the uninitiated, might serve neatly as Wieland 101. As this piece reveals, the choreographer, whose stern aesthetic may be related to the Bauhaus movement in his native Germany, favors austere architectural settings and groupings, along with a parallel emotional reticence.

Frederica Nascimento’s set for the piece features six austerely white boxes, two of which, with transparent “windows,” serve as cages—and, secondarily, jungle gyms—for a quintet of dancers (Julian Barnett, Brittany Beyer-Schubert, Nicholas Duran, Eliza Littrell, and Isadora Wolfe). In this bleak, handsome landscape, different but related activities occur simultaneously in various locations. Each of them is interesting on its own, while the stage picture as a whole is visually coherent, and, in that sense, meaningful. Here, as in his other works, Wieland proves himself to be more of a visual choreographer than a visceral one.

Needless to say, the set dehumanizes the dancers. The main box makes you think of a living-room aquarium, its confined denizens entirely at the mercy of random gazing eyes. When an inhabitant stands erect in the structure, the top of the frame cuts his head off from view. That overhead frame also conceals the equivalent of a chinning bar. Dancers inside the box hang from it at intervals. One woman swings from it upended, like a body taken from the gallows and hung to blow in the wind for passersby to notice, if they will.

The piece is handsome and ruthless—and part of its ferocity comes from the fact that both dancers and choreography do their best to seem affectless. But Wieland has another card up his sleeve. His dancers, who move with the sudden, lethal action of switchblades, are also extremely sensuous. Behind their lack of overt expression lies a potent universe of moods. Most of the feeling suggested is typical of our times—cool, subliminally hostile, and despairing. Nevertheless, it is there, working on the spectator’s emotions.

Parietal Region is clearly the ancestor of the new Corrosion, whose six dancers (the above, plus Branislav Henselmann) dwell in a recognizable contemporary world where love seems impossible. In changing-partners couples, they manipulate each others’ bodies, all the while apparently incapable of—perhaps immune to—effective communication. They seem more aware of invisible observers than they are of each other. An embrace is anatomized in slow motion; rites that should pass for intimate are performed eyeing the audience, as if gauging the anonymous public response. The prevailing climate is one of imminent disaster, though the piece never offers the catharsis of actual calamity. Just about every moment in it would make (does make) a still photo worthy of the high-end glossies.

Espen Sommer Eide provided the atmospheric electronic music for Corrosion, manipulating his equipment onstage. Diane von Furstenberg, who provided the theater for the concert—it’s part of her atelier, in the Manhattan’s fashionable Meatpacking District—designed the costumes. Much to her credit, the pearly gray outfits are suitably draped for the action of highly flexible, highly articulate bodies. The women’s dresses, translucent over their breasts, with skirts that cling to the hips, then flare out in clusters of pleats, make their wearers look like latter-day goddesses. The charm of both the men’s and the women’s outfits lies in the fact that they could be worn on the street in that downtown locale, where trendy restaurants and boutiques indicating fashion’s future spring up amid the persistent odor of dried blood.

The program included a newish trio, One, seemingly a three-ages-of-man affair. It’s full of Wieland trademarks, but vague in both its matter and meaning. Still, it was performed with distinction by two dance-world “elders”—the 65-year-old Gus Solomons jr, who, with one of the greatest mature faces in contemporary dance, brought to it a near-tragic dignity, and Keith Sabado, who, at 50, continues to be a paragon of delicate precision. Wieland himself—35, but an old soul—offered little more than physical fluidity coupled with a reservation so adamant, he seemed to be avoiding the audience’s scrutiny. I suppose this, in itself, is an artistic statement of sorts.

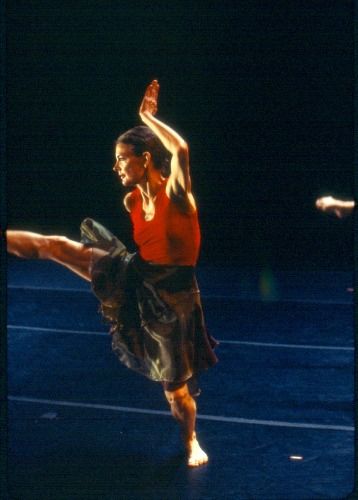

For me, the only dance on the program with more than visual or cerebral impact was the 2000 Tomorrow, named for and accompanied by the Richard Strauss song “Morgen!” (recorded by Jessye Norman) as well as passages of silence. Its “set” consists of three boxes, placed upstage, that are real aquariums. A trio of dancers (Barnett, Beyer-Schubert, and Littrell) lean over them to immerse their heads in the water for just a little longer than is comfortable to watch (and, no doubt, to do), then emerge from this near-death experience to splash the air and floor with giant droplets in wave-like arcs.

Though the dance then moves away from the tanks, it keeps returning to them. They are both objects and places, and they constitute the core of the piece. One of the women dips her brow and arm into the water in a singularly lovely gesture that might belong to a religious ritual. It suggests baptism, or a plea for—and gracious granting of—absolution. In a more violent (and typical) passage, the other woman (I think it is) holds the man’s head under water. This act—essentially inscrutable, as is much of what happens on Wieland’s stage—seems to lie somewhere between childish prank and erotically tinged cruelty. Later, the man, as if losing control, flings himself upon a tank and savagely strikes the surface of the water. The sound created by the impact is more terrifying than gunfire.

In between the encounters with the water there is much terrestrial thrashing about, much of it with the dancers sitting, lying, and rolling on the floor. More specific images of combat between an erect pair are witnessed by the third figure, whose arms and head hang limp, the very image of a person defeated by an environment that’s both hostile and hopeless and offers no viable alternatives.

The dancers wear silvery costumes by Stefanie Krimmel that might have been fashioned for postmodern garage attendants, and these designs are as integral to the piece as might be imagined.

I thought the whole business was fascinating and beautiful. It sold me, once again, on the idea that Wieland is a substantial talent. I wonder when—indeed, if—he’s going to unlock the box in which he’s confined himself among his personal obsessions.

Photo credit: Sebastian Lemm: Johannes Wieland’s Tomorrow

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

BODY LANGUAGE

Molissa Fenley and Dancers / The Kitchen, NYC / September 29 – October 9, 2004

More than a quarter-century after Molissa Fenley first appeared on the postmodern dance scene, an oddity in her way of moving—apparent throughout the cycles of solos and group works she’s choreographed—remains a distinct personal signature. She holds her hands sharply angled at the wrist, palms very flat, fingers tight together, thumb joined to them or splayed outward. This articulation, at once awkward and graceful, is accompanied by an unusual fluidity in the arms and a sentient pitch to her torso. It gives her a feral air, which is augmented by her intent concentration. She has passed this creature-like stance on—as far as any individual way of moving can be replicated—to the five women, at least a generation her junior, who joined her to perform some of her new and recent choreography in the first of two programs at the Kitchen. (The second, to run October 6-9, constitutes a revival of her 1983 Hemispheres.)

The look I’ve described proved to be most effective in the atmospheric sextet Kuro Shio, created in 2003. Set to music by Bun-Ching Lam called Like Water, this dance does, indeed, suggest an imagined natural world. The creatures disporting themselves in Evan Ayotte’s soft silvery jeans and translucent shimmering tops under David Moodey’s low, azure-filtered light might well be postmodern neriads. And while they are happily diverse in ethnicity, coloring, and body type, the dancers (Ashley Brunning, Tessa Chandler, Wanjiru Kamuyu, Cassie Mey, and Pan Tanjuaquio) are all clearly disciples of Fenley, who works among them, serving as the model for their inner-directed focus; their poised, unemphatic reiteration of gestures and groupings; the hieroglyphic work of their hands and arms.

The new piece, Lava Field, to John Bischoff’s Piano 7hz, is not as successful. It delivers a familiar Fenley message about the certain, if essentially unfathomable, connection among living things. In a kind of prelude, three women gently fit their bodies together. Lying on the ground, they move with the fluidity of molten lava—pouring in streams and coalescing in rivulets—as if they represented an ocean born of fire now lapsing into quiescence. When they’re erect, forming abstract stage patterns that allow them to disperse only to re-bond as parts of a matrix, the same principle holds. The implication is that interdependence, observable throughout inanimate nature, is no less present in human relationships.

The problem is that this is not exactly news and, in Lava Field, Fenley gives it no particular illumination or even intensity of statement.

Throughout the piece, the movement is very arm-y and leggy, as is this choreographer’s wont. Here you begin to wish—at least I did—that she would allow the mid-section of the body to take charge more, serve as an energy center, initiating the impulse for the dance and provide a compelling urgency in place of a calm that is neither hypnotic nor ecstatic but, rather, flaccid and monotonous.

From the first, I think, Fenley’s choreography has suffered from a condition that plagues all of modern dance—the limitations of a vocabulary derived largely from a single body’s instincts. It’s instructive to study how and to what degree some of the greats in the field—Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, Mark Morris—have escaped from the prison of self.

Photo credit: Paula Court: Molissa Fenley in her Lava Field.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

CARRYING ON

Limón Dance Company / Joyce Theater, NYC / September 21 – October 3, 2004

The Limón Dance Company is unabashedly old-fashioned. Adhering to the principles of its founder, José Limón, and his mentor, Doris Humphrey, it acquires new works that match its existing repertory—well-made dances on humanistic themes, the prevailing modern dance mode until things fell apart some four decades ago.

Phantasy Quintet, by Adam Hougland, a former dancer with the group, is a perfect example of the genre. Set to the gentle, evocative Ralph Vaughan Williams score from which it takes its title, it gives us a small community from which a young man and woman emerge and experience love for the first time. All freshness and rapture, the couple embodies the awakening of spring in a pastoral world, and the people surrounding the pair rightly recognize in it aspects of the divine. Hougland restricts himself to a small, suitably selected vocabulary—mostly lyrical stuff with some dynamic reinforcement from Graham technique—and pays careful attention to structural coherence throughout. His work is the antidote to the “whatever” method of choreography that today passes for cutting edge. His dance may be a shade too tautly controlled and just a little tame, but it is radiant, and that’s what you remember best.

Hougland’s all’s-right-with-the-world piece was aptly set back to back with Limón’s Psalm, a model of scrupulously crafted form shaping content that thrums the heartstrings. Created in 1967 and now performed to a score commissioned in 2002 from Jon Magnussen, Psalm is a long, somber, visionary work for a large ensemble and a male soloist. A program note for the piece refers the viewer to the ancient Jewish idea that a few chosen men act as vessels for the world’s griefs, preventing them from overwhelming humankind at large. But the dance easily accommodates alternative readings. In fact, it might be the mirror of today’s troubled world, with its agitated phalanxes of people in search of leader, cause, and—simply—meaning; its agonizingly tortured victim, whose patient suffering and expiring is repeated again and again; its brief but piercing moments of succor and empathy; its portraits of endurance; and its impulse to ecstasy. I saw the affecting Robert Regala (who looks like a saint rather than a hero) in the leading role, with Kristen Foote and Roxane D’Orléans Juste as ministering angels.

A brand-new work by the German neo-Expressionist choreographer Susanne Linke, about which I wrote a short preview piece for the Village Voice, provided another latter-day echo of Limón’s concern with human predicaments. Extreme Beauty, a quintet for women set to music by György Kurtág and Salvatore Sciarrino, seems to deal with the physical and social restrictions imposed on women by prevailing dress codes. The costumes, by Marion Williams, are indeed handsome and inventive, but the dance itself hasn’t gelled yet. Some segments, like the opening wall of fierce women that recalls Graham’s Heretic, go on too long without making any specific point. Others appear to be after a kind of wit at odds with the situation as a whole. (Borrowing the Schiaparelli hat that’s an upended stiletto just strikes the wrong note when you’re adorning your virgin bride with a crown of thorns.) What’s more, the performances themselves are not fully focused, and thus lack both individuality and power. Linke is best known for her introspective, even hallucinatory, solos; her performances of them are unforgettable. But here, not even the superb D’Orléans Juste, who plays the central figure, achieves the subtle textures and the riveting intensity she regularly offers elsewhere.

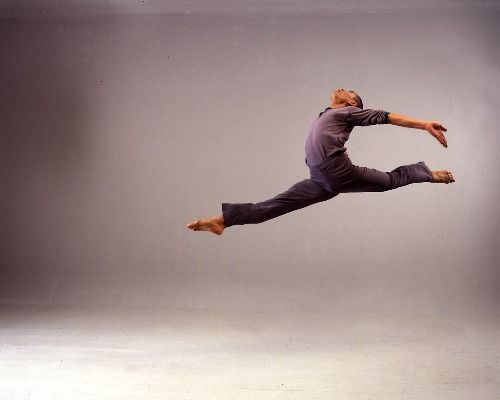

Elsewhere in the repertory, admirable dancing prevailed. On occasion it escalated to the level of glorious. Among the women, D’Orléans Juste carries on the tradition of Nina Watt and the company’s artistic director, Carla Maxwell—both now serving the Limón legacy behind the scenes—of senior dancers who grow increasingly profound with experience. Jonathan Riedel and Kurt Douglas are, to my mind, currently the outstanding men.

Douglas, with his innocent baby face and a chest that seems to have been sculpted by assiduous hours at the gym, is, first of all, very beautiful to look at. (Yes, looks count in the performing arts; it can’t be helped.) And he’s a formidable technician. In Limón’s The Unsung his downward plunges are infinitely lush; his aspirations upward, soaring in spirit as well as body. His huge buoyant jump animates the celebratory final section of Lar Lubovitch’s Concerto Six Twenty-Two as if it were the choreography’s motor. But the most important thing about him may be that he makes you instantly happy. His joy at moving in space is contagious. He makes you feel, body and soul, his own avidity.

Riedel is surely one of the most fascinating dancers the company has harbored. Entrusted with Chaconne, the famous long solo Limón made for himself in 1942 to a section of Bach’s Partita #2 in D minor, he did an exquisitely tempered job, failing to make the observer believe fully in the undertaking simply “because he wasn’t José.” Limón, one intuits from his choreography and the memory of his performances, enjoyed the blessing of single-mindedness. The world was a clear place for him, with right and wrong well defined and easily articulated. His impassioned vision gave him the courage of his convictions and the ability to turn them into drama. Riedel, by contrast, is a child of his times. He has the haunted looks of a fallen angel and always seems to be torn—often tormented—by conflicting forces. He represents, magnificently, the contemporary predicament. While Limon favored magisterial gesture that commanded the stage space and declared it to be the entire universe, Riedel treats space as if it were dangerous and his position in it equivocal. His balancing act—with its hints of the wildness (madness, even) that may go with playing the hero—is invariably compelling.

Photo credit: Beatriz Schiller: Robert Regala in José Limón’s Psalm

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Limón Dance Company

Carla Maxwell, artistic director of the Limón Dance Company: “Susanne [Linke] works from the inside out, striving for nuance and depth. The process is like a metamorphosis.” Village Voice 9/20/04

Decadancetheatre

The leading dancers of Jennifer Weber’s Decadancetheatre bring—dare I say?—the feminine mystique to hip-hop. Village Voice 9/14/04

Dances by Paul D. Mosley

Mosley’s evocation of the horrors that can breed in the roiling matrix of nuclear-family life rarely rises above soap opera level. Village Voice 9/8/04